Easter Island: Difference between revisions

→''Ahu'': add photo |

add creation of the island, some tidy up and links |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

|footnote2 = |

|footnote2 = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Easter Island''' (or ''Rapa Nui'' to the indigenous [[Rapanui]] people, or ''Isla de Pascua'' in [[Spanish language|Spanish]]), is a [[Chilean]] island in the south eastern [[Pacific Ocean]], |

'''Easter Island''' (or ''Rapa Nui'' to the indigenous [[Rapanui]] people, or ''Isla de Pascua'' in [[Spanish language|Spanish]]), is a [[Chilean]] island in the south eastern [[Pacific Ocean]], at the southeastern tip of the [[Polynesian triangle]]. Easter Island is famous for its enigmatic [[moai]] statues, and is a [[world heritage site]] with much of the island protected by the [[Rapa Nui National Park]]. |

||

==Name== |

==Name== |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

[[Image:Orthographic projection centred over Easter Island.png|right|thumb|Orthographic projection centered on [[Easter Island]].]] [[Image:Easter island and south america.jpg|left|thumb|[[Easter Island]], [[Sala y Gómez]], [[South America]] and the islands in between]] |

[[Image:Orthographic projection centred over Easter Island.png|right|thumb|Orthographic projection centered on [[Easter Island]].]] [[Image:Easter island and south america.jpg|left|thumb|[[Easter Island]], [[Sala y Gómez]], [[South America]] and the islands in between]] |

||

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. It is 3,600 km (2,237 [[mile]]s) west of continental Chile and 2,075 km (1,290 miles) east of [[Pitcairn Islands|Pitcairn]] |

[[Easter Island]] is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. It is 3,600 km (2,237 [[mile]]s) west of continental Chile and 2,075 km (1,290 miles) east of [[Pitcairn Islands|Pitcairn]] ([[Sala y Gómez]] 415 kilometres to the east is closer but uninhabited). |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Easter Island is |

||

===Geology=== |

|||

| ⚫ | Easter Island is a [[volcanic]] [[high island]], consisting of three extinct volcanoes: [[Terevaka]] (altitude 507 metres) forms the bulk of the island. Two other volcanoes [[Poike]] and [[Rano Kau]] form the Eastern and Southern headlands and give the island its approximately triangular shape. There are numerous lesser cones and other volcanic features, including the crater [[Rano Raraku]], the [[cinder cone]] [[Puna Pau]] and many volcanic caves including [[lava tubes]]. |

||

[[Easter Island]] and surrounding islets such as [[Motu Nui]] are the summit of a large volcanic mountain which rises thousands of metres from the sea bed. [[Easter Island]] and Sala y Gómez are the only parts of the '''Sala y Gómez Ridge''' above [[sea level]]. The '''Sala y Gómez Ridge''' is a mostly submarine mountain range with dozens of [[seamount]]s starting with Pukao and Moai, two sea mounts to the west of Easter Island, and extending 2700 km east to the '''Nazca Seamount''' at {{coor dm|23|36|S|83|30|W|}}, where it joins the [[Nazca Ridge]].{{ref|seamounts}} |

|||

Pukao, Moai and [[Easter Island]] were formed in the last three quarters of a million years, with the most recent eruption a little over a hundred thousand years ago; making them the youngest mountains of the '''Sala y Gómez Ridge''', which has been formed by the [[Nazca Plate]] floating over a [[Hotspot (geology)|hotspot]]. {{ref|hotspot}} <ref>ttp://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/petroj/online/Volume_38/Issue_06/default.html</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 131: | Line 138: | ||

[[Image:Rano-Kau-2b-Birdman-Cult.JPG|thumb|left|150px|[[Motu Nui]] islet, part of the Birdman Cult ceremony]] |

[[Image:Rano-Kau-2b-Birdman-Cult.JPG|thumb|left|150px|[[Motu Nui]] islet, part of the Birdman Cult ceremony]] |

||

For unknown reasons, a coup by military leaders called ''matatoa'' had brought a new cult based around a previously unexceptional god [[Make-make]]. In the cult of the birdman (Rapanui: ''[[tangata manu]]''), a competition was established in which every year a representative of each clan, chosen by the leaders, would |

For unknown reasons, a coup by military leaders called ''matatoa'' had brought a new cult based around a previously unexceptional god [[Make-make]]. In the cult of the birdman (Rapanui: ''[[tangata manu]]''), a competition was established in which every year a representative of each clan, chosen by the leaders, would swim across shark-infested waters to [[Motu Nui]], a nearby islet, to search for the season's first egg laid by a ''manutara'' ([[Sooty Tern|sooty tern]]). The first swimmer to return with an egg and successfully climb back up the cliff to [[Orongo]] would be named "Birdman of the year" and secure control over distribution of the island's resources for his clan for the year. The tradition was still in existence at the time of first contact by Europeans. It ended in 1867. The militant birdman cult was largely to blame for the island's misery of the late 18th and 19th centuries. Each year's winner and his supporters short-sightedly pillaged the island after the victory. With the island's ecosystem fading, destruction of crops quickly resulted in famine, sickness and death. |

||

===The "statue-toppling"=== |

===The "statue-toppling"=== |

||

| Line 144: | Line 151: | ||

The next foreign visitors on [[15 November]] [[1770]]; were two Spanish ships, ''San Lorenzo'' and ''Santa Rosalia'', sent by the [[Viceroy]] of [[Peru]], Manuel Amat, and commanded by [[Felipe González de Haedo]]. They spent five days in the island, performing a very thorough survey of its coast, and named it ''Isla de San Carlos'', taking possession on behalf of King [[Charles III of Spain]], and ceremoniously erected three wooden crosses on top of three small hills on [[Poike]].<ref> Jo Anne Van Tilburg. "Easter Island, Archaeology, Ecology and Culture". British Museum Press, London, 1994. ISBN 0-7141-2504-0</ref> |

The next foreign visitors on [[15 November]] [[1770]]; were two Spanish ships, ''San Lorenzo'' and ''Santa Rosalia'', sent by the [[Viceroy]] of [[Peru]], Manuel Amat, and commanded by [[Felipe González de Haedo]]. They spent five days in the island, performing a very thorough survey of its coast, and named it ''Isla de San Carlos'', taking possession on behalf of King [[Charles III of Spain]], and ceremoniously erected three wooden crosses on top of three small hills on [[Poike]].<ref> Jo Anne Van Tilburg. "Easter Island, Archaeology, Ecology and Culture". British Museum Press, London, 1994. ISBN 0-7141-2504-0</ref> |

||

Four years later, in [[1774]], British explorer [[James Cook]] |

Four years later, in [[1774]], British explorer [[James Cook]] visited Easter Island, he reported the statues as being neglected with some having fallen down. |

||

In 1786 French explorer, [[Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse|Jean François de Galaup La Pérouse]] visited and made a detailed map of Easter Island. |

In 1786 French explorer, [[Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse|Jean François de Galaup La Pérouse]] visited and made a detailed map of Easter Island. |

||

| Line 166: | Line 173: | ||

The first Christian missionary, Eugene Eyraud, arrived in January 1864 and spent most of that year on the island; but mass conversion of the [[Rapanui]] only came after his return in 1866 with [[Father Roussel]] and shortly after two others arrived with Captain [[Dutrou Bornier]]. Eyraud was suffering from [[Phthisis]] (Tuberculosis) when he returned and in 1867, tuberculosis raged over the island, taking a quarter of the island's remaining population of 1,200 including the last member of the island's royal family, the 13-year-old [[Manu Rangi]]. Eyraud died of tuberculosis in August 1868, by which time the entire Rapanui population had become [[Roman Catholic]]. |

The first Christian missionary, Eugene Eyraud, arrived in January 1864 and spent most of that year on the island; but mass conversion of the [[Rapanui]] only came after his return in 1866 with [[Father Roussel]] and shortly after two others arrived with Captain [[Dutrou Bornier]]. Eyraud was suffering from [[Phthisis]] (Tuberculosis) when he returned and in 1867, tuberculosis raged over the island, taking a quarter of the island's remaining population of 1,200 including the last member of the island's royal family, the 13-year-old [[Manu Rangi]]. Eyraud died of tuberculosis in August 1868, by which time the entire Rapanui population had become [[Roman Catholic]]. |

||

Bournier bought up all of the island apart from an area around [[Hanga Roa]] and shipped a couple of hundred Rapanui to work for his backers on [[Tahiti]], in 1871 the missionaries having fallen out with Bournier evacuated all but 171 Rapanui to the [[Gambier islands]]<ref>[[Katherine Routledge]] The mystery of Easter island page 208</ref> . Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, there were just 111 people living on Easter Island, and only 36 of them had any offspring.<ref>[http://www.rongorongo.org/cooke/712.html Collapse of island's demographics in the 1860s and 1870s].</ref> From that point on, the island population has slowly recovered. But with over 97% of the population |

Bournier bought up all of the island apart from an area around [[Hanga Roa]] and shipped a couple of hundred Rapanui to work for his backers on [[Tahiti]], in 1871 the missionaries having fallen out with Bournier evacuated all but 171 Rapanui to the [[Gambier islands]]<ref>[[Katherine Routledge]] The mystery of Easter island page 208</ref> . Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, there were just 111 people living on Easter Island, and only 36 of them had any offspring.<ref>[http://www.rongorongo.org/cooke/712.html Collapse of island's demographics in the 1860s and 1870s].</ref> From that point on, the island population has slowly recovered. But with over 97% of the population dead or left in less than a decade, much of the island's cultural knowledge had been lost. |

||

=== Annexation to Chile === |

=== Annexation to Chile === |

||

Easter Island was annexed by Chile on September 9, 1888, by [[Policarpo Toro]], by means of the "[[Treaty of Annexation of the island]]" (Tratado de Anexión de la isla), that the government of Chile signed with the |

Easter Island was annexed by Chile on September 9, 1888, by [[Policarpo Toro]], by means of the "[[Treaty of Annexation of the island]]" (Tratado de Anexión de la isla), that the government of Chile signed with the [[Rapanui]] people. |

||

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapanui were confined to the settlement of [[Hanga Roa]] because the island was rented to the [[Williamson-Balfour Company]] as a sheep farm until 1953. The island was then managed by the [[Chilean Navy]] until 1966 and at some point in this period the rest of the island was reopened. |

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapanui were confined to the settlement of [[Hanga Roa]] because the island was rented to the [[Williamson-Balfour Company]] as a sheep farm until 1953. The island was then managed by the [[Chilean Navy]] until 1966 and at some point in this period the rest of the island was reopened. |

||

=== Today === |

=== Today === |

||

Since being given Chilean citizenship in 1966, the Rapanui have re-embraced their ancient culture, or what could be reconstructed of it.<ref>Diamond, Jared (2005) "Collapse: How societies choose to fail or survive" p112</ref> |

Since being given Chilean citizenship in 1966, the Rapanui have re-embraced their ancient culture, or what could be reconstructed of it.<ref>Diamond, Jared (2005) "Collapse: How societies choose to fail or survive" p112</ref> |

||

[[Mataveri International Airport]] is the island's only airport. In the 1980s, its runway was lengthened by the U.S. space program to 3,318 m (10,885 ft) so that it could serve as an emergency landing site for the [[space shuttle]]. This enabled regular wide body jet services and a consequent increase of tourism on the island, coupled with migration of people from mainland Chile which threatens to alter the [[Polynesian culture|Polynesian]] identity of the island. Land disputes have created political tensions since the 1980s, with part of the native [[Rapanui]] opposed to private property and in favor of traditional communal property (see ''Demography'' below). |

[[Mataveri International Airport]] is the island's only airport. In the 1980s, its runway was lengthened by the U.S. space program to 3,318 m (10,885 ft) so that it could serve as an emergency landing site for the [[space shuttle]]. This enabled regular wide body jet services and a consequent increase of tourism on the island, coupled with migration of people from mainland Chile which threatens to alter the [[Polynesian culture|Polynesian]] identity of the island. Land disputes have created political tensions since the 1980s, with part of the native [[Rapanui]] opposed to private property and in favor of traditional communal property (see ''Demography'' below). |

||

| Line 182: | Line 189: | ||

== Ecology == |

== Ecology == |

||

[[Image:RapaNui L7 03jan01.jpg|thumb|View of Easter Island from space, 2001]] |

[[Image:RapaNui L7 03jan01.jpg|thumb|View of [[Easter Island]] from space, 2001]] |

||

Easter Island, together with its closest neighbour, the tiny island of [[Isla Sala y Gómez]] |

Easter Island, together with its closest neighbour, the tiny island of [[Isla Sala y Gómez]] 415 km further East, is recognized by ecologists as a distinct [[ecoregion]], the '''Rapa Nui subtropical broadleaf forests'''. Having relatively little rainfall contributed to eventual deforestation. The original [[tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests|subtropical moist broadleaf forests]] are now gone, but [[paleobotany|paleobotanical]] studies of fossil [[pollen]] and tree moulds left by lava flows indicate that the island was formerly forested, with a range of [[tree]]s, [[shrub]]s, [[fern]]s, and [[grass]]es. A large [[Arecaceae|palm]], related to the [[Chilean wine palm]] ''([[Jubaea]] chilensis)'' was one of the dominant trees, as was the [[toromiro]] tree ''([[Sophora]] toromiro)''. The palm is now extinct, and the toromiro is extinct in the wild. However the [[Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew]] and the [[Göteborg Botanical Garden]], are jointly leading a scientific program to reintroduce the toromiro to Easter Island. The island for the last three centuries at least is mainly covered in [[grassland]] with [[totora (plant)|nga'atu or bulrush]] in the crater lakes of [[Rano Raraku]] and [[Rano Kau]]. Presence of these reeds (which are called ''totora'' in the Andes) was used to support the argument of a South American origin of the statue builders, but pollen analysis of lake sediments shows these reeds have grown on the island for over 30,000 years. Before the arrival of humans, Easter Island had vast seabird colonies, no longer found on the main island, and several species of landbirds, which have become [[extinction|extinct]]. |

||

===Destruction of the ecosystem=== |

===Destruction of the ecosystem=== |

||

| Line 193: | Line 200: | ||

[[Tree]]s are sparse on modern Easter Island, rarely forming small [[grove (nature)|grove]]s. The island once possessed a forest of palms and it has generally been thought that native Easter Islanders deforested the island in the process of erecting their statues.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} Experimental archaeology has clearly demonstrated that some statues certainly could have been placed on wooden frames and then pulled to their final destinations on ceremonial sites. Rapanui traditions metaphorically refer to spiritual power (mana) as the means by which the moai were "walked" from the quarry. However, given the island's southern latitude, the (as yet poorly documented) climatic effects of the [[Little Ice Age]] (about 1650 to 1850) may have contributed to deforestation and other changes. [[Jared Diamond]] disregards the influence of climate in the collapse of the ancient Easter Islanders in his book ''[[Collapse (book)|Collapse]]''. The disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of the Easter Island civilization around the 17th-18th century. [[Midden]] contents show a sudden drop in quantities of fish and bird bones as the islanders lost the means to construct fishing vessels and the birds lost their nesting sites. Soil erosion due to lack of trees is apparent in some places. Sediment samples document that up to half of the native plants had become extinct and that the vegetation of the island was drastically altered. Chickens and rats became leading items of diet and there are (not unequivocally accepted) hints at [[cannibalism]] occurring, based on human remains associated with cooking sites, especially in caves. |

[[Tree]]s are sparse on modern Easter Island, rarely forming small [[grove (nature)|grove]]s. The island once possessed a forest of palms and it has generally been thought that native Easter Islanders deforested the island in the process of erecting their statues.{{Fact|date=July 2007}} Experimental archaeology has clearly demonstrated that some statues certainly could have been placed on wooden frames and then pulled to their final destinations on ceremonial sites. Rapanui traditions metaphorically refer to spiritual power (mana) as the means by which the moai were "walked" from the quarry. However, given the island's southern latitude, the (as yet poorly documented) climatic effects of the [[Little Ice Age]] (about 1650 to 1850) may have contributed to deforestation and other changes. [[Jared Diamond]] disregards the influence of climate in the collapse of the ancient Easter Islanders in his book ''[[Collapse (book)|Collapse]]''. The disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of the Easter Island civilization around the 17th-18th century. [[Midden]] contents show a sudden drop in quantities of fish and bird bones as the islanders lost the means to construct fishing vessels and the birds lost their nesting sites. Soil erosion due to lack of trees is apparent in some places. Sediment samples document that up to half of the native plants had become extinct and that the vegetation of the island was drastically altered. Chickens and rats became leading items of diet and there are (not unequivocally accepted) hints at [[cannibalism]] occurring, based on human remains associated with cooking sites, especially in caves. |

||

In his article ''From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui'', [[Benny Peiser]] notes evidence of self-sufficiency on Easter Island when Europeans first arrived. Although stressed, the island may still have had at least some (small) trees remaining, mainly [[toromiro]]. Cornelis Bouman, [[Jakob Roggeveen]]'s captain, stated in his log book, "...of yams, bananas and small coconut palms we saw little and no other trees or crops." According to [[Carl Friedrich Behrens]], Roggeveen's officer, "The natives presented palm branches as peace offerings. Their houses were set up on wooden stakes, daubed over with luting and covered with palm leaves," (presumably from [[Banana]] plants as the island was by then deforested) the stakes indicate that |

In his article ''From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui'', [[Benny Peiser]] notes evidence of self-sufficiency on Easter Island when Europeans first arrived. Although stressed, the island may still have had at least some (small) trees remaining, mainly [[toromiro]]. Cornelis Bouman, [[Jakob Roggeveen]]'s captain, stated in his log book, "...of yams, bananas and small coconut palms we saw little and no other trees or crops." According to [[Carl Friedrich Behrens]], Roggeveen's officer, "The natives presented palm branches as peace offerings. Their houses were set up on wooden stakes, daubed over with luting and covered with palm leaves," (presumably from [[Banana]] plants as the island was by then deforested) the stakes indicate that either driftwood or living trees were still available, though the reliability of Behrens as a source is questionable{{Fact|date=May 2007}}. Peiser however considers these reports to indicate that considerable amounts of large trees still existed at that time, which is explicitly contradicted by the Roggeveen quote above. |

||

In his book "A Short History of Progress", Ronald Wright speculates that for a generation or so, "there was enough old lumber to haul the great stones and still keep a few canoes seaworthy for deep water". When the day came the last boat was gone, wars broke out over "ancient planks and wormeaten bits of jetsam". The people of Rapa Nui exhausted all possible resources, including eating their own dogs and all nesting birds when finally there was absolutely nothing left. All that was left were the stone giants who symbolized the devouring of a whole island. The stone giants became monuments where the islanders could keep faith and honour them in hopes of a return. |

In his book "A Short History of Progress", Ronald Wright speculates that for a generation or so, "there was enough old lumber to haul the great stones and still keep a few canoes seaworthy for deep water". When the day came the last boat was gone, wars broke out over "ancient planks and wormeaten bits of jetsam". The people of Rapa Nui exhausted all possible resources, including eating their own dogs and all nesting birds when finally there was absolutely nothing left. All that was left were the stone giants who symbolized the devouring of a whole island. The stone giants became monuments where the islanders could keep faith and honour them in hopes of a return. |

||

| Line 230: | Line 237: | ||

==== [[Moai]] (Statues) ==== |

==== [[Moai]] (Statues) ==== |

||

{{Main|Moai}} |

{{Main|Moai}} |

||

[[Image:Moai and Esmeralda.jpg|thumb|left|Moai |

[[Image:Moai and Esmeralda.jpg|thumb|left|Moai with replica eyes at Ahu Ko Te Riku in [[Hanga Roa]], with [[Chilean Navy]] ship ''[[Buque Escuela Esmeralda]]'' behind.]] |

||

The large stone statues, or ''moai'', for which Easter Island is world famous were carved during a relatively short and intense burst of creative and productive megalithic activity. According to recent archaeological research, 887 monolithic stone statues have been inventoried on the island and in museum collections. Although often identified as "Easter Island Heads", the statues actually are heads and complete torsos. Some upright moai, however, have become buried up to their necks by shifting soils. |

The large stone statues, or ''moai'', for which Easter Island is world famous were carved during a relatively short and intense burst of creative and productive megalithic activity. According to recent archaeological research, 887 monolithic stone statues have been inventoried on the island and in museum collections. Although often identified as "Easter Island Heads", the statues actually are heads and complete torsos. Some upright moai, however, have become buried up to their necks by shifting soils. |

||

| Line 237: | Line 244: | ||

Most currently standing statues, some 50 in total, have been re-erected in modern times, except for those on the slopes of Rano Raraku. |

Most currently standing statues, some 50 in total, have been re-erected in modern times, except for those on the slopes of Rano Raraku. |

||

[[Image:Kneeled moai Easter Island.jpg|thumb|right| |

[[Image:Kneeled moai Easter Island.jpg|thumb|right|[[Rano Raraku#Tukuturi|Tukuturi]] an unusual bearded kneeling [[moai]].]] |

||

While the vast majority of Moai follow a fairly standard design there are a few radically different moai on the island, in most parts badly eroded and broken. These are believed to predate the better-known moais, including a kneeling statue with hands on its knees, parts of a statue with clearly carved ribs and a headless, rectangularly shaped torso. Similarities to Indian stone statues around [[Lake Titicaca]] in South America are striking, whether this is accidental or not.<ref>See Heyerdahl, with pictures.</ref> |

While the vast majority of Moai follow a fairly standard design there are a few radically different moai on the island, in most parts badly eroded and broken. These are believed to predate the better-known moais, including a kneeling statue with hands on its knees, parts of a statue with clearly carved ribs and a headless, rectangularly shaped torso. Similarities to Indian stone statues around [[Lake Titicaca]] in South America are striking, whether this is accidental or not.<ref>See Heyerdahl, with pictures.</ref> |

||

| Line 276: | Line 283: | ||

====Petroglyphs==== |

====Petroglyphs==== |

||

''[[Petroglyphs]]'' are pictures carved into rock, and Easter Island has one of the richest collections in all Polynesia. Around 1000 sites with more than 4000 [[petroglyph]]s are catalogued. Designs and images were carved out of rock for variety of reasons: to create totems, to mark territory or to memorialize a person or event. There are distinct variations around the island in terms of the frequency of particular themes among Petroglyphs, with a concentration of [[Birdmen (Rapa Nui)|Birdmen]] at [[Orongo]]. Other subjects include sea turtles, Komari (vulvas) and [[Make-make]] the chief god of the "[[Tangata manu]]" or ''bird-man'' cult. |

''[[Petroglyphs]]'' are pictures carved into rock, and Easter Island has one of the richest collections in all [[Polynesia]]. Around 1000 sites with more than 4000 [[petroglyph]]s are catalogued. Designs and images were carved out of rock for variety of reasons: to create totems, to mark territory or to memorialize a person or event. There are distinct variations around the island in terms of the frequency of particular themes among Petroglyphs, with a concentration of [[Birdmen (Rapa Nui)|Birdmen]] at [[Orongo]]. Other subjects include sea turtles, Komari (vulvas) and [[Make-make]] the chief god of the "[[Tangata manu]]" or ''bird-man'' cult. |

||

Petroglyphs are also common in the [[Marquesas]] islands. |

Petroglyphs are also common in the [[Marquesas]] islands. |

||

| Line 291: | Line 298: | ||

=== Rongorongo === |

=== Rongorongo === |

||

{{main|Rongorongo}} |

{{main|Rongorongo}} |

||

[[Image:Rongo-rongo script.gif|thumb|right|150px|Sample of Rongorongo |

[[Image:Rongo-rongo script.gif|thumb|right|150px|Sample of [[Rongorongo]].]] |

||

The undeciphered Easter island script [[Rongorongo]] may be one of the very few writing systems created ''[[ex nihilo]]'', without outside influence. Alternatively the islanders' brief but very visible exposure to Western writing during the Spanish visit in 1770 inspired the ruling class to establish Rongorongo as a religious tool.<ref>See Fischer, page 63.</ref> |

The undeciphered Easter island script [[Rongorongo]] may be one of the very few writing systems created ''[[ex nihilo]]'', without outside influence. Alternatively the islanders' brief but very visible exposure to Western writing during the Spanish visit in 1770 inspired the ruling class to establish Rongorongo as a religious tool.<ref>See Fischer, page 63.</ref> |

||

Rongorongo was first reported by a French missionary [[Eugène Eyraud]] in 1864. At that time, several islanders still claimed to be able to understand the scripture, but all attempts to read them were unsuccessful. According to traditions, only a small part of the population was ever literate, Rongorongo being a privilege of the ruling families and priests. This contributed to the total loss of knowledge of how to read Rongorongo in the 1860s, when the island's elite was annihilated by slave raids and disease. |

|||

Of the hundreds of wooden tablets and staffs reportedly having Rongorongo writing carved on them, only 26 survive,<ref> images of them are at [http://www.rongorongo.org www.rongorongo.org].</ref> all in museums around the world and none remaining on Easter Island. Decades of numerous attempts to decipher them have been unfruitful. The scientific community don't even agree on whether or not Rongorongo is truly a form of writing. |

Of the hundreds of wooden tablets and staffs reportedly having Rongorongo writing carved on them, only 26 survive,<ref> images of them are at [http://www.rongorongo.org www.rongorongo.org].</ref> all in museums around the world and none remaining on Easter Island. Decades of numerous attempts to decipher them have been unfruitful. The scientific community don't even agree on whether or not Rongorongo is truly a form of writing. |

||

| Line 305: | Line 312: | ||

Wood was scarce on Easter Island during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but a number of highly detailed and distinctive carvings have found their way to the world's museums. Particular forms include <ref>The mystery of Easter island, routledge page 268</ref>: |

Wood was scarce on Easter Island during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but a number of highly detailed and distinctive carvings have found their way to the world's museums. Particular forms include <ref>The mystery of Easter island, routledge page 268</ref>: |

||

* [[Rei-miro]] a [[gorget]] or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips<ref>http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/w/wooden_gorget_rei_miro.aspx</ref>. The same design appears in some petroglyphs especially at [[Orongo]] |

* [[Rei-miro]] a [[gorget]] or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips<ref>http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/w/wooden_gorget_rei_miro.aspx</ref>. The same design appears on the [[Flag of Easter Island|Rapanui flag]] and in some petroglyphs especially at [[Orongo]]. |

||

* Moko-Miro a man with a lizard head |

* Moko-Miro a man with a lizard head |

||

| Line 319: | Line 326: | ||

* An annual cultural festival, the ''Tapati'', celebrating [[Rapanui]] culture. |

|||

* A [[Easter Island national football team|"National"]] [[Football (Soccer)|Football team]]. |

* A [[Easter Island national football team|"National"]] [[Football (Soccer)|Football team]]. |

||

* Three [[discos]] in the town of [[Hanga Roa]] |

* Three [[discos]] in the town of [[Hanga Roa]] |

||

| Line 393: | Line 401: | ||

* LEE, Georgia. 1992. The Rock Art of Easter Island. Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. Los Angeles: The Institute of Archaeology Publications (UCLA). |

* LEE, Georgia. 1992. The Rock Art of Easter Island. Symbols of Power, Prayers to the Gods. Los Angeles: The Institute of Archaeology Publications (UCLA). |

||

* MELLÉN BLANCO, Francisco. 1986. Manuscritos y documentos españoles para la historia de la isla de Pascua. Madrid: CEHOPU. |

* MELLÉN BLANCO, Francisco. 1986. Manuscritos y documentos españoles para la historia de la isla de Pascua. Madrid: CEHOPU. |

||

* MÉTRAUX, Alfred. 1940. Ethnology of Easter Island. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 160. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum Press. |

* [[Alfred Metraux|MÉTRAUX, Alfred]]. 1940. Ethnology of Easter Island. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 160. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum Press. |

||

* POZDNIAKOV, Konstantin. 1996. Les Bases du Déchiffrement de l'Écriture de l'Ile de Pâques. Journal de la Societé des Océanistes 103:2.289-303. |

* POZDNIAKOV, Konstantin. 1996. Les Bases du Déchiffrement de l'Écriture de l'Ile de Pâques. Journal de la Societé des Océanistes 103:2.289-303. |

||

* ROUTLEDGE, Katherine. 1919. The Mystery of Easter Island. The story of an expedition. London. |

* [[Katherine Routledge|ROUTLEDGE, Katherine]]. 1919. The Mystery of Easter Island. The story of an expedition. London. |

||

* THOMSON, William J. 1891. Te Pito te Henua, or Easter Island. Report of the United States National Museum for the Year Ending [[June 30]], [[1889]]. Annual Reports of the Smithsonian Institution for 1889. 447-552. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. |

* THOMSON, William J. 1891. Te Pito te Henua, or Easter Island. Report of the United States National Museum for the Year Ending [[June 30]], [[1889]]. Annual Reports of the Smithsonian Institution for 1889. 447-552. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. |

||

* VAN TILBURG, Jo Anne. 1994. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. |

* VAN TILBURG, Jo Anne. 1994. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. |

||

| Line 417: | Line 425: | ||

* [http://exn.ca/mysticplaces/EIsland.cfm Easter Island] |

* [http://exn.ca/mysticplaces/EIsland.cfm Easter Island] |

||

* [http://www.southpacific.org/text/finding_easter.html Finding Easter Island] |

* [http://www.southpacific.org/text/finding_easter.html Finding Easter Island] |

||

* [http://www.netaxs.com/~trance/rongo.html Rongorongo, the hieroglyphic script of Easter Island |

* [http://www.netaxs.com/~trance/rongo.html Rongorongo, the mysterious hieroglyphic script of Easter Island] |

||

* [http://www.mapsouthpacific.com/easter_island/index.html Map of Easter Island] from Map South Pacific |

* [http://www.mapsouthpacific.com/easter_island/index.html Map of Easter Island] from Map South Pacific |

||

* [http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/islands_oceans_poles/easterisland.jpg Map of Easter Island] from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. |

* [http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/islands_oceans_poles/easterisland.jpg Map of Easter Island] from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. |

||

| Line 425: | Line 433: | ||

* [http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/oc/oc0111_full.html Rapa Nui subtropical broadleaf forests] ([[World Wide Fund for Nature]]) |

* [http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/oc/oc0111_full.html Rapa Nui subtropical broadleaf forests] ([[World Wide Fund for Nature]]) |

||

* {{PDFlink|[http://www.staff.livjm.ac.uk/spsbpeis/EE%2016-34_Peiser.pdf From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui]|116 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 118999 bytes -->}} by Benny Peiser |

* {{PDFlink|[http://www.staff.livjm.ac.uk/spsbpeis/EE%2016-34_Peiser.pdf From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui]|116 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 118999 bytes -->}} by Benny Peiser |

||

* [http://polyscience.org/interviews/bill-basener/ Interview with Bill Basener, |

* [http://polyscience.org/interviews/bill-basener/ Interview with Bill Basener, who created a mathematical model of the society's collapse] |

||

* [http://www.sacred-destinations.com/easter-island/easter-island-pictures/index.htm Easter Island Photo Gallery] - 75 photos |

* [http://www.sacred-destinations.com/easter-island/easter-island-pictures/index.htm Easter Island Photo Gallery] - 75 photos |

||

* [http://www.pacific-pictures.com/easter_island/index.html Easter Island Travel Photos] by the author of Moon Handbooks South Pacific |

* [http://www.pacific-pictures.com/easter_island/index.html Easter Island Travel Photos] by the author of Moon Handbooks South Pacific |

||

| Line 435: | Line 443: | ||

* [http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/easter/index.php Easter Island] The Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui |

* [http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/easter/index.php Easter Island] The Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui |

||

* [http://www.rapanuicentral.com Rapa Nui Central] History, photos, stamps and postal history of Easter Island |

* [http://www.rapanuicentral.com Rapa Nui Central] History, photos, stamps and postal history of Easter Island |

||

* ''[http://www.pacsoa.org.au/palms/Paschalococos/disperta.html Paschalococos disperta]'' - information on the Easter Island palm by |

* ''[http://www.pacsoa.org.au/palms/Paschalococos/disperta.html Paschalococos disperta]'' - information on the Easter Island palm by John Dransfield |

||

{{Polynesia}} |

{{Polynesia}} |

||

Revision as of 22:07, 30 August 2007

Easter Island/Isla de Pascua Rapa Nui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Hanga Roa |

| Official languages | Spanish, Rapa Nui |

| Ethnic groups (2002) | Rapanui 60%, Chileano 39%, Amerindian 1% |

| Demonym(s) | Rapanui or Pascuense |

| Government | Special territory within Valparaíso Region of Chile |

• Provincial governor | Melania Carolina Hotu Hey |

| Pedro Pablo Edmunds Paoa | |

| Annexation to Chile | |

• Treaty signed | September 9 1888 |

| Population | |

• 2002 census | 3,791 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Time Zone) |

| Calling code | 32 |

Easter Island (or Rapa Nui to the indigenous Rapanui people, or Isla de Pascua in Spanish), is a Chilean island in the south eastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeastern tip of the Polynesian triangle. Easter Island is famous for its enigmatic moai statues, and is a world heritage site with much of the island protected by the Rapa Nui National Park.

Name

On Easter Sunday, 1722 Easter Island was found and named by its first recorded European visitor, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who was searching for Davis or David's island.[1] The island's official Spanish name, Isla de Pascua, is Spanish for "Easter Island".

The current Polynesian name of the island, Rapa Nui or "Big Rapa", was coined by labor immigrants from Rapa in the Bass Islands, who likened it to their home island in the aftermath of the Peruvian slave deportations in the 1870s.[2] However, Thor Heyerdahl has claimed that the naming would have been the opposite, Rapa being the original name of Easter Island and Rapa Iti named by its refugees.[3]

There are several options for the "original" Polynesian name for Easter Island. Including Te pito o te henua, or the "The Navel of the World" due to its isolation. Legends claim that the island was first named as Te pito o te kainga a Hau Maka, or the "Little piece of land of Hau Maka".[4]

Location and physical geography

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands. It is 3,600 km (2,237 miles) west of continental Chile and 2,075 km (1,290 miles) east of Pitcairn (Sala y Gómez 415 kilometres to the east is closer but uninhabited).

It has a latitude close to that of Caldera, Chile, an area of 163.6 km² (63 sq. miles), and a maximum altitude of 507 metres. There are two Rano (freshwater Crater lakes) at Rano Kau and Rano Raraku, but no permanent streams or rivers.

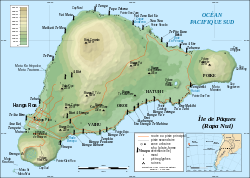

Geology

Easter Island is a volcanic high island, consisting of three extinct volcanoes: Terevaka (altitude 507 metres) forms the bulk of the island. Two other volcanoes Poike and Rano Kau form the Eastern and Southern headlands and give the island its approximately triangular shape. There are numerous lesser cones and other volcanic features, including the crater Rano Raraku, the cinder cone Puna Pau and many volcanic caves including lava tubes.

Easter Island and surrounding islets such as Motu Nui are the summit of a large volcanic mountain which rises thousands of metres from the sea bed. Easter Island and Sala y Gómez are the only parts of the Sala y Gómez Ridge above sea level. The Sala y Gómez Ridge is a mostly submarine mountain range with dozens of seamounts starting with Pukao and Moai, two sea mounts to the west of Easter Island, and extending 2700 km east to the Nazca Seamount at 23°36′S 83°30′W / 23.600°S 83.500°W, where it joins the Nazca Ridge.[1]

Pukao, Moai and Easter Island were formed in the last three quarters of a million years, with the most recent eruption a little over a hundred thousand years ago; making them the youngest mountains of the Sala y Gómez Ridge, which has been formed by the Nazca Plate floating over a hotspot. [2] [5]

History

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, v |

| Reference | 715 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

First settlers

Early European visitors to Easter Island recorded the local oral traditions of the original settlers. In these traditions, Easter Islanders claimed that a chief Hotu Matu'a[6] arrived on the island in one or two large canoes with his wife and extended family.[7] They are believed to have been Polynesian. There is considerable uncertainty about the accuracy of this legend as well as the date of settlement. Published literature suggests the island was settled around 300-400 CE, or at about the time of the arrival of the earliest settlers in Hawaii. Some scientists say that Easter Island was not inhabited until 700-800 CE. This date range is based on glottochronological calculations and on three radiocarbon dates from charcoal that appears to have been produced during forest clearance activities.[8] On the other hand, a recent study, including radiocarbon dates from what is thought to be very early material, suggests that the island was settled as recently as 1200 CE.[9] This seems to be supported by the latest information on island's deforestation that could have started around the same time. [10] Any earlier human activity seems to be insignificant, if it existed at all.

The Austronesian Polynesians, who first settled the island, are likely to have arrived from the Marquesas Islands from the west. These settlers brought bananas, taro, sweet potato, sugarcane, and paper mulberry, as well as chickens and rats. The island at one time supported a relatively advanced and complex civilization.

The Norwegian ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl pointed out many cultural similarities between Easter Island and South American Indian cultures which he suggested might have resulted from some settlers arriving also from the continent.[11] According to local legends, a group of long-eared[12] unknown men called as hanau epe[13] had arrived on the island sometime after Polynesians, introducing the stone carving technology and attempting to enslave the local Polynesians.[14] Some early accounts of the legend place hanau epe as the original residents and Polynesians as later immigrants coming from Oparo.[15] After mutual suspicions erupted in a violent clash, the hanau epe were overthrown and exterminated, leaving only one survivor.[16] The first description of island's demographics by Jacob Roggeveen in 1722 still claimed that the population consisted of two distinctive ethnic groups, one being clearly Polynesian and the other "white" with so lengthened earlobes that they could tie them behind their necks[verification needed]. Roggeveen also noted how some of the islanders were "generally large in stature". Islanders' tallness was also witnessed by the Spanish who visited the island in 1770, measuring heights of 196 and 199 cm.[17]

The fact that sweet potatoes, a staple of the Polynesian diet, and several other domestic plants - up to 12 in Easter Island - are of South American origin indicates that there may have been some contact between the two cultures. Either Polynesians have traveled to South America and back, or Indian balsa rafts have drifted to Polynesia, possibly unable to make a return trip because of their less developed navigational skills and more fragile boats, or both. Polynesian connections in South America have been noticed among the Mapuche Indians in central and southern Chile.[18] The Polynesian name for the small islet of Sala y Gómez (Manu Motu Motiro Hiva, "Bird's islet on the way to a far away land") east of Easter Island has also been seen as a hint that South America was known before European contacts. Further complicating the situation is that the word Hiva ("far away land") was also the name of the islanders' legendary home country. Inexplicable insistence on an eastern origin for the first inhabitants was unanimous among the islanders in all early accounts.[19]

Today mainstream archeology is skeptical about any non-Polynesian influence on the island's prehistory, although the discussion has become political. DNA sequence analysis of Easter Island's current inhabitants (a tool not available in Heyerdahl's time) offers strong evidence of Polynesian origins. However, since few islanders survived the 19th century deportations (perhaps only 1-2% of the peak population) this confirms a Polynesian origin only for the remaining population.

Pre-European society

According to legends recorded by the missionaries in the 1860s, the island originally had a very clear class system, with an ariki, king, wielding absolute god-like power ever since Hotu Matua had arrived on the island. The most visible element in the culture was production of massive moai that were part of the ancestral worship. With a strictly unified appearance, moai were erected along the entire coastline, indicating a homogeneous culture and centralized governance. In addition to the royal family, the island's habitation consisted of priests, soldiers and commoners. The last king, along with his family, died as slaves in the 1860s in the Peruvian mines. Long before that, the king had become a mere symbolic figure, remaining respected and untouchable, but having nominal authority.

For unknown reasons, a coup by military leaders called matatoa had brought a new cult based around a previously unexceptional god Make-make. In the cult of the birdman (Rapanui: tangata manu), a competition was established in which every year a representative of each clan, chosen by the leaders, would swim across shark-infested waters to Motu Nui, a nearby islet, to search for the season's first egg laid by a manutara (sooty tern). The first swimmer to return with an egg and successfully climb back up the cliff to Orongo would be named "Birdman of the year" and secure control over distribution of the island's resources for his clan for the year. The tradition was still in existence at the time of first contact by Europeans. It ended in 1867. The militant birdman cult was largely to blame for the island's misery of the late 18th and 19th centuries. Each year's winner and his supporters short-sightedly pillaged the island after the victory. With the island's ecosystem fading, destruction of crops quickly resulted in famine, sickness and death.

The "statue-toppling"

European accounts from 1722 and 1770 still saw only standing statues, but by Cook's visit in 1774 many were reported toppled. The huri mo'ai - the "statue-toppling" - continued into the 1830s as a part of fierce internecine wars. By 1838 the only standing Moai were on the outer slopes of Rano Raraku and Hoa Hakananai'a at Orongo. In about 60 years, islanders had deliberately destroyed the main part of their ancestors' heritage.[20] In modern times Moai have been restored at Orongo, Ahu Tongariki, Ahu Akivi and Hanga Roa.

European contacts

The first recorded European contact with the island was on 5 April (Easter Sunday) 1722 when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen visited for a week and estimated there were 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants on the island (this was an estimate not a census and archaeologists estimate the population may have been as high as 10,000 to 15,000 a few decades earlier). His party reported "remarkable, tall, stone figures, a good 30 feet in height", the island had rich soil and a good climate and "all the country was under cultivation". Fossil Pollen analysis shows that the main trees on the island had gone 72 years earlier in 1650. The civilization of Easter Island was long believed to have degenerated drastically during the century before the arrival of the Dutch, as a result of overpopulation, deforestation and exploitation of an extremely isolated island with limited natural resources. The Dutch reported that a fight broke out in which they killed ten or twelve islanders.

The next foreign visitors on 15 November 1770; were two Spanish ships, San Lorenzo and Santa Rosalia, sent by the Viceroy of Peru, Manuel Amat, and commanded by Felipe González de Haedo. They spent five days in the island, performing a very thorough survey of its coast, and named it Isla de San Carlos, taking possession on behalf of King Charles III of Spain, and ceremoniously erected three wooden crosses on top of three small hills on Poike.[21]

Four years later, in 1774, British explorer James Cook visited Easter Island, he reported the statues as being neglected with some having fallen down.

In 1786 French explorer, Jean François de Galaup La Pérouse visited and made a detailed map of Easter Island.

In 1804, the Russian ship, Neva, visited under the command of Yuri Lisyansky.

In 1816, the Russian ship, Rurik, visited under the command of Otto von Kotzebue.

In 1825, the British ship, HMS Blossom, visited and reported no standing statues.

Easter Island was approached many times during the 19th century, but by now the islanders had become openly hostile towards any attempt to land, and very little new information was reported before the 1860s.

Destruction of society and population

A series of devastating events killed almost the entire population of Easter Island in the 1860s.

In December 1862, slave raiders collecting labour for the Peruvian Guano mines struck Easter Island. Violent abductions continued for several months, eventually capturing or killing around 1500 men and women, about half of the island's population. International protests erupted, escalated by Bishop Florentin Jaussen of Tahiti. The slaves were finally freed in autumn, 1863, but by then most of them had already died of tuberculosis, smallpox and dysentery. Finally, a dozen islanders managed to return from the horrors of Peru, but brought with them smallpox and started an epidemic which decimated the island's population to the point where some of the dead were not even buried.

Contributing to the chaos were violent clan wars with the remaining people fighting over the newly available lands of the deceased, bringing further famine and death among the dwindling population.

The first Christian missionary, Eugene Eyraud, arrived in January 1864 and spent most of that year on the island; but mass conversion of the Rapanui only came after his return in 1866 with Father Roussel and shortly after two others arrived with Captain Dutrou Bornier. Eyraud was suffering from Phthisis (Tuberculosis) when he returned and in 1867, tuberculosis raged over the island, taking a quarter of the island's remaining population of 1,200 including the last member of the island's royal family, the 13-year-old Manu Rangi. Eyraud died of tuberculosis in August 1868, by which time the entire Rapanui population had become Roman Catholic.

Bournier bought up all of the island apart from an area around Hanga Roa and shipped a couple of hundred Rapanui to work for his backers on Tahiti, in 1871 the missionaries having fallen out with Bournier evacuated all but 171 Rapanui to the Gambier islands[22] . Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, there were just 111 people living on Easter Island, and only 36 of them had any offspring.[23] From that point on, the island population has slowly recovered. But with over 97% of the population dead or left in less than a decade, much of the island's cultural knowledge had been lost.

Annexation to Chile

Easter Island was annexed by Chile on September 9, 1888, by Policarpo Toro, by means of the "Treaty of Annexation of the island" (Tratado de Anexión de la isla), that the government of Chile signed with the Rapanui people.

Until the 1960s, the surviving Rapanui were confined to the settlement of Hanga Roa because the island was rented to the Williamson-Balfour Company as a sheep farm until 1953. The island was then managed by the Chilean Navy until 1966 and at some point in this period the rest of the island was reopened.

Today

Since being given Chilean citizenship in 1966, the Rapanui have re-embraced their ancient culture, or what could be reconstructed of it.[24]

Mataveri International Airport is the island's only airport. In the 1980s, its runway was lengthened by the U.S. space program to 3,318 m (10,885 ft) so that it could serve as an emergency landing site for the space shuttle. This enabled regular wide body jet services and a consequent increase of tourism on the island, coupled with migration of people from mainland Chile which threatens to alter the Polynesian identity of the island. Land disputes have created political tensions since the 1980s, with part of the native Rapanui opposed to private property and in favor of traditional communal property (see Demography below).

On July 30 2007, a constitutional reform gave Easter Island and Juan Fernández Islands the status of special territories of Chile. Pending the enactment of a special charter, the island will continue to be governed as a province of the Valparaíso Region.[25]

Ecology

Easter Island, together with its closest neighbour, the tiny island of Isla Sala y Gómez 415 km further East, is recognized by ecologists as a distinct ecoregion, the Rapa Nui subtropical broadleaf forests. Having relatively little rainfall contributed to eventual deforestation. The original subtropical moist broadleaf forests are now gone, but paleobotanical studies of fossil pollen and tree moulds left by lava flows indicate that the island was formerly forested, with a range of trees, shrubs, ferns, and grasses. A large palm, related to the Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis) was one of the dominant trees, as was the toromiro tree (Sophora toromiro). The palm is now extinct, and the toromiro is extinct in the wild. However the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Göteborg Botanical Garden, are jointly leading a scientific program to reintroduce the toromiro to Easter Island. The island for the last three centuries at least is mainly covered in grassland with nga'atu or bulrush in the crater lakes of Rano Raraku and Rano Kau. Presence of these reeds (which are called totora in the Andes) was used to support the argument of a South American origin of the statue builders, but pollen analysis of lake sediments shows these reeds have grown on the island for over 30,000 years. Before the arrival of humans, Easter Island had vast seabird colonies, no longer found on the main island, and several species of landbirds, which have become extinct.

Destruction of the ecosystem

"The overall picture for Easter is the most extreme example of forest destruction in the Pacific, and among the most extreme in the world: the whole forest gone, and all of its tree species extinct."[26] Diamond's conclusions of direct native influence as the underlying cause have been challenged by Hunt (2006) (see reference list). After his research, Hunt concluded that the original immigrants arrived ca. 1200 CE, three to four hundred years later than the generally accepted date and that immediately upon arriving the Polynesians began to fell their forests. This would imply that the islanders did not live for a period of time in an idyllic balance with their environment. Hunt also asserts that the trees were lost because rats which came with the settler's ate the seeds, and much of the population loss was due to capture by slave traders.

Hunt's conclusions, however, are themselves questioned by another researcher of Polynesian history, Patrick V. Kirch, archaeologist at the University of California at Berkeley. "A first arrival on Easter Island around 900 AD would fit well with Polynesians' first arrival on the nearest neighbouring islands of Mangareva, Henderson and Pitcairn.... Kirch thinks Hunt and Lipo may have been too free in discarding studies for minor methodological problems, thus rejecting valid dates in this range. 'For me, they don't make a convincing argument that we can eliminate the earlier dates, especially in light of the broader regional context'" [3]. In addition, Hunt (2006) elaborates at length on his claim that Polynesian rats were mainly responsible for the extinction of the endemic palms. His argument is flawed for two reasons: [citation needed] First, he assumes that because Polynesian rats are known to have made a major impact on Hawaiian Pritchardia palms which have fleshy fruits and small seeds, they were able to have the same impact on the rather distantly related Easter Island palm with its very hard endocarp. Second, he entirely ignores the results of Hunter-Anderson (1998) who showed that at least in the Chilean Wine Palm (which is closely related to the Easter Island species), mechanical abrasion actually facilitates seed germination. Hunt implies that the "gnawed" palm seeds on Easter Island were all "eaten" without providing evidence for this assertion, whereas the available evidence points to a minor net impact of the rats (some seeds were likely eaten, but others would have germinated more easily). Toromiro seeds are probably very toxic (as usual in Sophora species) and thus probably were not eaten by the rats in numbers.

Trees are sparse on modern Easter Island, rarely forming small groves. The island once possessed a forest of palms and it has generally been thought that native Easter Islanders deforested the island in the process of erecting their statues.[citation needed] Experimental archaeology has clearly demonstrated that some statues certainly could have been placed on wooden frames and then pulled to their final destinations on ceremonial sites. Rapanui traditions metaphorically refer to spiritual power (mana) as the means by which the moai were "walked" from the quarry. However, given the island's southern latitude, the (as yet poorly documented) climatic effects of the Little Ice Age (about 1650 to 1850) may have contributed to deforestation and other changes. Jared Diamond disregards the influence of climate in the collapse of the ancient Easter Islanders in his book Collapse. The disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of the Easter Island civilization around the 17th-18th century. Midden contents show a sudden drop in quantities of fish and bird bones as the islanders lost the means to construct fishing vessels and the birds lost their nesting sites. Soil erosion due to lack of trees is apparent in some places. Sediment samples document that up to half of the native plants had become extinct and that the vegetation of the island was drastically altered. Chickens and rats became leading items of diet and there are (not unequivocally accepted) hints at cannibalism occurring, based on human remains associated with cooking sites, especially in caves.

In his article From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui, Benny Peiser notes evidence of self-sufficiency on Easter Island when Europeans first arrived. Although stressed, the island may still have had at least some (small) trees remaining, mainly toromiro. Cornelis Bouman, Jakob Roggeveen's captain, stated in his log book, "...of yams, bananas and small coconut palms we saw little and no other trees or crops." According to Carl Friedrich Behrens, Roggeveen's officer, "The natives presented palm branches as peace offerings. Their houses were set up on wooden stakes, daubed over with luting and covered with palm leaves," (presumably from Banana plants as the island was by then deforested) the stakes indicate that either driftwood or living trees were still available, though the reliability of Behrens as a source is questionable[citation needed]. Peiser however considers these reports to indicate that considerable amounts of large trees still existed at that time, which is explicitly contradicted by the Roggeveen quote above.

In his book "A Short History of Progress", Ronald Wright speculates that for a generation or so, "there was enough old lumber to haul the great stones and still keep a few canoes seaworthy for deep water". When the day came the last boat was gone, wars broke out over "ancient planks and wormeaten bits of jetsam". The people of Rapa Nui exhausted all possible resources, including eating their own dogs and all nesting birds when finally there was absolutely nothing left. All that was left were the stone giants who symbolized the devouring of a whole island. The stone giants became monuments where the islanders could keep faith and honour them in hopes of a return. By the end, there were more than a thousand moai (stone statues), which was one for every ten islanders (Wright, 2004). When the Europeans arrived in the eighteenth century, the worst was over and they only found one or two living souls per statue.

Easter Island has suffered from heavy soil erosion during recent centuries, perhaps aggravated by agriculture and massive deforestation. However, this process seems to have been gradual and may have been aggravated by extensive sheep farming throughout most of the 20th century. Jakob Roggeveen reported that Easter Island was exceptionally fertile, producing large quantities of bananas, potatoes and thick sugar-cane. In 1786 M. de La Pérouse visited Easter Island and his gardener declared that "three day's work a year" would be enough to support the population.

Rollin, a major of the French expedition to Easter Island in 1786, wrote, "Instead of meeting with men exhausted by famine... I found, on the contrary, a considerable population, with more beauty and grace than I afterwards met in any other island; and a soil, which, with very little labour, furnished excellent provisions, and in an abundance more than sufficient for the consumption of the inhabitants." [27]

The fact that oral traditions of the islanders are obsessed with cannibalism is evidence supporting a rapid collapse. For example, to severely insult an enemy one would say: "The flesh of your mother sticks between my teeth." This suggests that the food supply of the people ultimately ran out.[28]

Culture

Mythology

The most important myths are:

- Hotu Matu'a The legendary founder of the island.

- Tangata manu The Birdman cult which was practiced until the 1860s

- Make-make An important God.

Stone work

Rapa Nui is a volcanic island consisting of geologically recent igneous rock. The Rapa Nui people had a stone age civilisation and made extensive use of several different types of indigenous stone:

- Basalt a hard dense stone was used for toki and at least one of the moai.

- Obsidian a volcanic glass with sharp edges was used for sharp edged implements such as Mataa and also for the black pupils of the eyes of the moai.

- Tuff from Rano Raraku a much more easily worked rock than Basalt was used for most of the moai.

Moai (Statues)

The large stone statues, or moai, for which Easter Island is world famous were carved during a relatively short and intense burst of creative and productive megalithic activity. According to recent archaeological research, 887 monolithic stone statues have been inventoried on the island and in museum collections. Although often identified as "Easter Island Heads", the statues actually are heads and complete torsos. Some upright moai, however, have become buried up to their necks by shifting soils.

The period of time when the statues were produced remains disputed, with estimates ranging from 1000/1500 CE to 1500/1700 CE. Almost all (95%) moais were carved out of distinctive, compressed, easily-worked volcanic ash or tuff found at a single site called Rano Raraku. The Rapanui who carved them had no metal or powered machinery, only stone hand tools - mainly basalt toki. Only a quarter of the statues ever made it to the coastal ahu platforms, with nearly half still remaining in Rano Raraku and the rest elsewhere on the island, probably on their ways to final locations. Moving the huge statues seems to have been laborious and very slow.

Most currently standing statues, some 50 in total, have been re-erected in modern times, except for those on the slopes of Rano Raraku.

While the vast majority of Moai follow a fairly standard design there are a few radically different moai on the island, in most parts badly eroded and broken. These are believed to predate the better-known moais, including a kneeling statue with hands on its knees, parts of a statue with clearly carved ribs and a headless, rectangularly shaped torso. Similarities to Indian stone statues around Lake Titicaca in South America are striking, whether this is accidental or not.[29]

Ahu

Ahus are stone platforms that some of the Moai were erected on. They vary greatly in layout and many have been significantly reworked in the islands during or after the huri mo'ai or statue-toppling era; many became ossuaries, one was dynamited open and Ahu Tongariki was swept inland by a tsunami.

The classic elements of Ahu design are:

- A retaining rear wall several feet high, usually facing the sea.

- A platform behind the wall.

- Pads or cushions on the platform

- A sloping ramp covered with evenly sized wave rounded boulders on the inland side of the platform rising most but not all the way up the side of the platform.

- A pavement in front of the ramp.

- Inside the Ahu was a fill of rubble.

On top of many Ahu would have been:

- Moai on the pads looking out over the pavement with their backs to the rear wall.

- Pukau on the Moai's heads.

- And in their eye sockets, white coral eyes with black obsidian pupils.

Ahus evolved from the traditional Polynesian Marae in which the word Ahu was only used for the central stone platform, though on Easter Island Ahus and Moai evolved to a much greater size. The biggest Ahus contained 20 times as much stone as a Moai; however most of this stone was sourced very locally (apart from broken old moai, fragments of which have also been used in the fill).[30] Also individual stones are mostly far smaller than the Moai, so less work was needed to transport the raw material.

Ahus are mostly on the coast where they are distributed fairly evenly except on the Western slopes of Mount Terevaka, and the Rano Kau and Poike [31] headlands. These are the three areas with the least low lying coastal land, and apart from Poike the furthest areas from Rano Raraku. One Ahu with several Moai was recorded on the cliffs at Rano Kau in the 1880s, but had fallen to the beach by the time of the Routledge expedition in 1914.

Of the 313 known ahus, only 125 carried a stone moai. Others perhaps had statues made of wood, now lost. The majority of the rest had just one moai, probably due to the shortness of the moai period and difficulties in transporting them. Ahu Tongariki, one kilometer from Rano Raraku, had the most and biggest moai, 15 in total. Other notable Ahus with moais were Ahu Akivi, Naunau at Anakena and Tahai.

Stone walls

One of the highest quality examples of Easter Island stone-masonry is the rear wall of the Ahu at Vinapu. Made without mortar by shaping hard Basalt rocks of up to seven tonnes to match each other exactly. It has a superficial similarity to some Inca stone walls in South America.[32]

Stone houses

Some 1,233 prehistoric stone "houses" called tupa in earlier times[33] and hare moa ("chicken house") later, are more conspicuous than the remains of the prehistoric human houses which only had stone foundations (except for those at Orongo. Stone houses were up to 6 meters long, with a distinctive boat shaped structure combined with a stick and palm leaf or thatch superstructure. The entrances were very low, and getting in required crawling.

Germans excavated some of the Hare Moa in 1882 and found human remains inside. Locals told them that they were resting places for the ariki, Eastern Island kings and chiefs. Each house had two small holes - if a hostile spirit entered through one, the spirit of the deceased could escape through another. As such and also by their old name, the stone houses are seen similar to Indian chullpas in Peru and Bolivia.[34] Noteworthy is that the remaining numbers of the stone houses and moais are quite close to each other, possibly meaning that for each person buried in a stone house, a moai was immediately constructed. Usage of stone houses as graves seems to have ceased around the same time when production of moais ended and ancestral worship declined. During the turmoils of the late 18th century, the islanders seem to have started to bury their dead among the ruined ahus, the moai platforms, and use the stone houses as chicken shelters. There are no human remains in any of them any more.

Petroglyphs

Petroglyphs are pictures carved into rock, and Easter Island has one of the richest collections in all Polynesia. Around 1000 sites with more than 4000 petroglyphs are catalogued. Designs and images were carved out of rock for variety of reasons: to create totems, to mark territory or to memorialize a person or event. There are distinct variations around the island in terms of the frequency of particular themes among Petroglyphs, with a concentration of Birdmen at Orongo. Other subjects include sea turtles, Komari (vulvas) and Make-make the chief god of the "Tangata manu" or bird-man cult.

Petroglyphs are also common in the Marquesas islands.

-

Turtle petroglyph found near Ahu Tongariki

Caves

The island and neighbouring Motu Nui are riddled with caves many of which show signs of past human use and fortification, including narrowed entrances and crawl spaces with ambush points. Many caves feature in the myths and legends of the Rapa Nui.

Rongorongo

The undeciphered Easter island script Rongorongo may be one of the very few writing systems created ex nihilo, without outside influence. Alternatively the islanders' brief but very visible exposure to Western writing during the Spanish visit in 1770 inspired the ruling class to establish Rongorongo as a religious tool.[35] Rongorongo was first reported by a French missionary Eugène Eyraud in 1864. At that time, several islanders still claimed to be able to understand the scripture, but all attempts to read them were unsuccessful. According to traditions, only a small part of the population was ever literate, Rongorongo being a privilege of the ruling families and priests. This contributed to the total loss of knowledge of how to read Rongorongo in the 1860s, when the island's elite was annihilated by slave raids and disease.

Of the hundreds of wooden tablets and staffs reportedly having Rongorongo writing carved on them, only 26 survive,[36] all in museums around the world and none remaining on Easter Island. Decades of numerous attempts to decipher them have been unfruitful. The scientific community don't even agree on whether or not Rongorongo is truly a form of writing.

Legends claim that Hotu Matu'a brought the original tablets with him when he first landed at Anakena, however as Metraux pointed out, the largest tablet is made from a European oar. Also as there is not a single line of Rongorongo carved in stone despite thousands of Rapanui petroglyphs and other remarkable stonework, Rongorongo probably originated on Easter Island in a rather late period.

The Rongorongo script has similarities to the petroglyph corpus, and may have been inspired by it.[37]

Wood Carving

Wood was scarce on Easter Island during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but a number of highly detailed and distinctive carvings have found their way to the world's museums. Particular forms include [38]:

- Rei-miro a gorget or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips[39]. The same design appears on the Rapanui flag and in some petroglyphs especially at Orongo.

- Moko-Miro a man with a lizard head

- Moai-Miro human images often emaciated and sometimes with long ears.

- Ao a large dancing paddle

Contemporary culture

The Rapa Nui have:

- An annual cultural festival, the Tapati, celebrating Rapanui culture.

- A "National" Football team.

- Three discos in the town of Hanga Roa

- A musical tradition that combines South American and Polynesian influences

- A vibrant carving tradition with much to offer tourists.

Demography

2002 Census

Population at the 2002 census was 3,791, (3,304 of them in Hanga Roa). Only 60% were Rapanui. Chileans of European descent were 39% of the population, and the remaining 1% were Native American from mainland Chile.

Rapanui have also migrated out of the island. At the 2002 census there were 2,269 Rapanui living in Easter Island, while 2,378 Rapanui lived in the mainland of Chile (half of them in the metropolitan area of Santiago)[citation needed].

Population density on Easter Island is only 23 inhabitants per km² (60 inh. per sq. mile), much lower than in the 17th century heyday of the moai building when there were possibly as many as 15,000 inhabitants.

Demographic history

The population was 1,936 inhabitants in 1982. This increase in population is partly due to the arrival of people of European descent from the mainland of Chile. Consequently, the island is losing its native Polynesian identity. In 1982 around 70% of the population were Rapanui (the native Polynesian inhabitants). Population had already declined to only 2,000-3,000 inhabitants before the slave raids of 1862. In the 19th century, disease due to contacts with Europeans, as well as deportation of 2,000 Rapanui to work as slaves in Peru, and the forced departure of the remaining Rapanui to Chile, carried the population of Easter Island to the all time low of 111 inhabitants in 1877. Out of these 111 Rapanui, only 36 had descendants, but all of today's Rapanui claim descent from those 36.

Administration

Region

Easter Island is a province of the Valparaíso Region of Chile.

The Provincial Governor is Melania Carolina Hotu Hey

Local Council

Easter Island has only one municipality, the town of Hanga Roa whose Mayor is Pedro Pablo Edmunds Paoa (PDC)

Hanga Roa's Councillors are:

- Hipólito Juan Icka Nahoe — PH (Humanist Party)

- Eliana Amelia Olivares San Juan — UDI

- Nicolás Haoa Cardinali — Independent, center-right

- Marcelo Icka Paoa — PDC

- Alberto Hotus Chávez — PPD

- Marcelo Pont Hill — PPD

Famous people

- Itto Pakarati - musician and surfer

- Hotuiti Teao - model

- Hotu Matua - founder

- Pedro Pablo Edmunds Paoa - Mayor

See also

References

- ^ An English translation of the originally Dutch journal by Jacob Roggeveen, with additional significant information from the log by Cornelis Bouwman, was published in: Andrew Sharp (ed.), The Journal of Jacob Roggeveen (Oxford 1970).

- ^ Invention of the name "Rapa Nui"

- ^ Heyerdahl claimed that the two islands would be about the same size, meaning that "big" and "small" would not be physical, but historical attributes, "big" indicating the original. In reality, however, Easter Island is more than four times bigger than Rapa Iti. Heyerdahl also claimed that there is an island called "Rapa" in Lake Titicaca in South America, but so far there is no map available showing an island of that name in the lake.

- ^ Thomas S. Barthel: The Eighth Land: The Polynesian Settlement of Easter Island (Honolulu: University of Hawaii 1978; originally published in German in 1974)

- ^ ttp://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/petroj/online/Volume_38/Issue_06/default.html

- ^ Resemblance of the name to an early Mangarevan founder god Atu Motua ("Father Lord") has made some historians suspect that Hotu Matua was added to Easter Island mythology only in the 1860s, along with adopting the Mangarevan language. The "real" founder would have been Tu'u ko Iho, who became just a supporting character in Hotu Matu'a centric legends. See Steven Fischer (1994). Rapanui's Tu'u ko Iho Versus Mangareva's 'Atu Motua. Evidence for Multiple Reanalysis and Replacement in Rapanui Settlement Traditions, Easter Island. The Journal of Pacific History, 29(1), 3-18. See also Rapa Nui / Geography, History and Religion. Peter H. Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, University of Chicago Press, 1938. pp. 228-236. Online version.

- ^ Summary of Thomas S. Barthel's version of Hotu Matu'a's arrival to Easter Island.

- ^ Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin Books: 2005. ISBN 0-14-303655-6. Chapter 2: Twilight at Easter pp.79-119. See page 89.

- ^ Hunt, T. L., Lipo, C. P., 2006. Science, 1121879. See also "Late Colonization of Easter Island" in Science Magazine. Entire article is also hosted by the Department of Anthropology of the University of Hawaii.

- ^ Hunt, Terry L. (2006), "Rethinking the Fall of Easter Island", American Scientist, 94 (5): pp. 412-419

{{citation}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Heyderdahl, Thor. Easter Island - The Mystery Solved. Random House New York 1989.

- ^ There is no doubt that the Polynesian elite practiced ear-lengthening on Easter Island until the late 19th century, but its possible origin from South America has been noted. The Inca chiefs were called Orejones, "big ears," by the Spaniards because the lobes of their ears had been enlarged artificially to receive the great gold earrings which they were fond of wearing. See Inca Land - Explorations in the Highlands of Peru by Hiram Bingham, 1912. Online version.

- ^ There is a dispute whether this should be spelled as hanau eepe or hanau epe. "Eepe" is a Polynesian word for "stocky" while the word "epe", specific to Easter Island only, means the earlobe. See Sebastian Englert's Rapa Nui dictionary with original Spanish translated to English. All early accounts of the legend spell the word "hanau epe". See Heyerdahl.

- ^ Compare this with South American traditions recorded in the 16th century, in which the Inca Emperor Tupac Inca Yupanqui is credited to have undertaken an almost year-long Pacific exploration around 1480, encountering "black people" and finding islands Nina and Hahua chumpi. The same legend claims that occasional travels oversees were done already earlier. See History of the Incas by Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, 1572. Online version of the book, page 91; in English.

- ^ This version was recorded by Doctor J.L. Palmer in 1868. See Heyerdahl. It must be noted, however, that the legends may be influenced by the situation of the 1860s: fierce fighting ensued on the island when the remaining population and returning immigrants fought for the land and resources.

- ^ The "Hanau Eepe", their Immigration and Extermination.

- ^ See Heyerdahl.