Instant-runoff voting: Difference between revisions

MilesAgain (talk | contribs) |

→Evaluation by criteria: extend specifications in language. |

||

| Line 259: | Line 259: | ||

===Evaluation by criteria=== |

===Evaluation by criteria=== |

||

Scholars of electoral systems often compare them using mathematically-defined [[voting system criterion|voting system criteria]], the value of some of which is controversial. Some of the criteria are considered by [[Arrow's Theorem]] and the [[Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem]], which assume that voters rank in a strict preference order, among other assumptions that do not hold for all methods. For methods such as IRV which use ranked preferences, satisfying all of |

Scholars of electoral systems often compare them using mathematically-defined [[voting system criterion|voting system criteria]], the value of some of which is controversial. Some of the criteria are considered by [[Arrow's Theorem]] and the [[Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem]], which assume that voters rank in a complete strict (exclusive) preference order, among other assumptions that do not hold for all methods. For methods such as IRV which use purely ranked preferences, satisfying all of those assumptions and criteria is impossible, as they are mutually exclusive. |

||

* IRV passes the [[majority criterion]], the [[later-no-harm criterion]], the [[mutual majority criterion]], the [[Condorcet loser criterion]] and, if the right tie-breaker method is used, the [[independence of clones]] criterion. |

* IRV passes the [[majority criterion]], the [[later-no-harm criterion]], the [[mutual majority criterion]], the [[Condorcet loser criterion]] and, if the right tie-breaker method is used, the [[independence of clones]] criterion. |

||

Revision as of 22:21, 13 December 2007

- For other types of Run-off voting systems, see Run-off voting.

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Instant-runoff voting (IRV) is a voting system used for single-winner elections in which voters have one vote, but can rank candidates in order of preference. In an IRV election, if no candidate receives a majority of first choices, the candidate with the fewest number of votes is eliminated, and ballots cast for that candidate are redistributed to the surviving candidates according to the voters' indicated preference. This process is repeated until one candidate obtains a majority. The term 'instant runoff voting' is used because this process simulates a series of run-off elections. In some implementations a winner may be declared with less than a majority of ballots cast, based on a plurality in the last round. In other implementations, the failure of any candidate to obtain a majority will result in a runoff or other process.

IRV is also referred to as alternative voting or the Alternative Vote (AV) in the United Kingdom, the preferential ballot in Canada, preferential voting in Australia, and sometimes ranked choice voting in the U.S. It is also referred to as the Hare system or Hare method, after Thomas Hare, an inventor of single transferable vote (STV) because IRV is the same as STV for a single seat election.

At a national level IRV is used to elect the Australian House of Representatives[1], the President of Ireland, the national parliament of Papua New Guinea and the Fijian House of Representatives. In the United States, it has been adopted in at least ten local jurisdictions, including three large population cities and counties during the 2006 United States general elections. In the United Kingdom, a form of IRV is used to elect the mayor of London. Robert's Rules of Order recommends a form of IRV for elections by mail.

Terminology

Instant runoff voting has a number of other names. In the United States it is called instant runoff voting primarily because of its resemblance to runoff voting, which is also used in that country and many presidential elections around the world. It has occasionally been referred to as Ware's method, after its U.S. proponent, William Robert Ware. Writers differ as to whether or not they treat instant runoff voting as a proper noun.

When the single transferable vote (STV) system is applied to a single-winner election it becomes the same as IRV. For this reason IRV is sometimes considered to be merely a special form of STV. However, because STV was designed for multi-seat constituencies, many scholars consider it to be a separate system from IRV, and that is the convention followed in this article. IRV is usually known simply as "STV" in New Zealand and Ireland, although the term Alternative Vote is also used in those countries.

Marking a ranked ballot

In IRV (as well as other ranked election methods) the voter ranks the list of candidates in order of preference. Under a common ballot layout (as shown in the image to the right), ascending numbers are used, whereby the voter places a '1' beside the most preferred candidate, a '2' beside the second-most preferred, and so forth.

Each voter casts only one vote, but during the process of counting votes, the vote may be redistributed and counted for the next sequential preference allocated to any remaining candidate that has not been earlier excluded from the count. In some implementations of IRV, the voter is allowed to rank as many or as few choices as the voter wishes, while in other implementations the voter is required to rank all of the candidates, and in still other cases the voter is allowed to rank only a set number of choices.

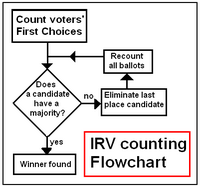

Counting the votes

|

In an IRV election, every ballot has one vote, but also expresses a rank order preference of candidates which may be used in later rounds if the voter's first (and if applicable, subsequent) choice candidates are eliminated.

|

Batch-style

IRV batch-style is a two-round variation of IRV where if no candidate receives a majority of the first round choices, all candidates but the top two are eliminated and all ballots are recounted for whichever of these two finalists is ranked higher on each ballot.

See Instant-runoff voting#Contingent vote.

Example

Imagine an election in which there are three candidates: Andrew, Brian and Catherine. There are 100 voters and they vote as follows (for clarity, third preferences are omitted):

| # | 39 voters | 10 voters | 4 votes | 5 voters | 42 voters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Andrew | Brian | Brian | Brian | Catherine |

| 2nd | Brian | Andrew | Catherine | Brian |

The first choices are counted, and the tallies are:

- Catherine: 42

- Andrew: 39

- Brian: 19

- -----------

- Total: 100

No candidate has a majority of votes (51 votes), so last place Brian is eliminated. The 2nd choices on Brian's ballots are 10 for Andrew, 5 for Catherine and 4 exhausted (no 2nd choice). The ballots become:

| # | 39 voters | 10 voters | 4 votes | 5 voters | 42 voters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Andrew | Catherine | |||

| 2nd | Andrew | Catherine |

The new top choices on each ballot are counted:

- Andrew: 49 (gained 10)

- Catherine: 47 (gained 5)

- -----------

- Total: 96

- Exhausted: 4

Andrew wins the runoff round with 49 votes.

Note: Andrew has 49/96 (51%) of the votes in round 2, but only 49% of the original 100 votes. This demonstrates that IRV can't guarantee a winner being supported by majority of total ballots if some voters offered no preferences among the final two candidates.

Handling ties

Exact ties can happen in any election; although the odds remain very low when many votes are cast, the multiple rounds of counting used in IRV create more opportunities for a tie than there are in some other voting systems. If there is a tie for last place in the elimination process, various rules can be used to break it:

- One candidate, from among those tied, is eliminated at random (e.g. by a coin toss).

- In Australia the candidate, from among those tied, with the fewest votes in the previous round is eliminated. If there is still a tie those counting votes then look back to the next most recent round and then, if necessary, to further progressively earlier rounds until one candidate can be eliminated.

- In Irish presidential elections, the candidate, from among those tied, with fewest first choices is eliminated. If this cannot break the tie, ballot-counters look forwards, first to find the tied candidate with fewest votes in the second round and then, if necessary, to the third, fourth and subsequent rounds.

- In some private elections the method is to 'conditionally eliminate' candidates from the tie and recount to see if either (or any) can survive. Usually the full set will become eliminated in any order.

In practice, before any of these methods are used, the first step is to see if a tie has any chance of actually affecting the result. If the total of all the combined votes of any grouping of the candidates with the fewest votes is fewer than the votes cast for the next weakest candidate, then all those bottom tier candidates can be eliminated simultaneously.

Ballot paper

As seen above, voters in an IRV election rank candidates on a preferential ballot. IRV systems in use in different countries vary both as to ballot design and as to whether or not voters are obliged to provide a full list of preferences. In elections such as those for the President of Ireland and the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, voters are permitted to rank as many or as few candidates as they wish. This is known in Australia as 'optional preferential voting'.

Under optional preferential voting some voters may rank only the candidates of a single party, or of their most preferred parties. Some voters may 'bullet vote', expressing only a first choice. Allowing voters to rank only as many candidates as they wish grants them greater freedom but can also lead to some voters ranking so few candidates that their vote eventually becomes 'exhausted'–that is, at a certain point during the count it can no longer be counted for a continuing candidate and therefore loses an opportunity to influence the result.

To prevent exhausted ballots, some IRV systems require or request that voters give a complete ordering of all of the candidates in an election - if a voter does not rank all candidates her ballot may be considered spoilt or an informal ballot. In Australia this variant is known as 'full preferential voting', and is used in elections for the federal House of Representatives and in most states. However, when there is a large set of candidates this requirement may prove burdensome and can lead to "donkey voting" in which, where a voter has no strong opinions about his or her lower preferences, the voter simply chooses them at random or in top-to-bottom order. Partly to overcome these problems, in elections to the Australian House of Representatives many parties distribute 'how-to-vote' cards (right), recommending how to allocate preferences on the ballot paper.

The common way to list candidates on a ballot paper is alphabetically or by random lot, a process whereby the order of the candidates published on the ballot paper is determined by lottery. In some cases candidates may also be grouped by party.

Any fixed ordering of candidates on the ballot paper will give some candidates an unfair advantage, because voters, consciously or otherwise, are influenced in their ordering of candidates by the order on the ballot paper. The random ordering of candidates is intended to overcome this. The most effective form is Robson Rotation, a system where the order of candidates on the paper is randomly changed for each print run of the same election's ballot papers. This means that any one ballot paper is almost certainly different from the next.

History and current use

Instant runoff voting was invented around 1870 by American architect William Robert Ware. He evidently based IRV on the single-winner outcome of the Single Transferable Vote, originally developed by Carl Andrae and Thomas Hare. The first known use of IRV in a governmental election was in 1893 in an election for the colonial government of Queensland, in Australia. The system used for this election was a special form known as the contingent vote. IRV in its true form was first used in 1908 in a State election in Western Australia.

Today IRV is used in Australia for elections to the Federal House of Representatives, and for the lower houses of all States and Territories except Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory, which use STV. It is also used for the Legislative Council of Tasmania. In the Pacific, IRV is used for the Fijian House of Representatives, and Papua New Guinea has adopted it for its parliamentary elections. IRV is also used to elect the President of Ireland and for municipal elections in various places in Australia, the United States, and New Zealand.

United States

- San Francisco, California has used instant runoff voting annually to elect its Board of Supervisors and major citywide offices since 2004 after voter passage in 2002 [2]. Several elections have gone to an instant runoff. </ref>[6]</ref>

- Basalt, Colorado adopted instant runoff voting in 2002 for mayoral elections in which there are at least three candidates </ref> [7]</ref>

- Ferndale, Michigan passed (68%) instant runoff voting in 2004 pending implementation[3].

- Berkeley, California passed (72%) instant runoff voting in 2004 pending implementation[4].

- Burlington, Vermont held its first mayoral election using IRV in 2006 after voters approved it with a 64% vote in 2005. Bob Kiss received 39.2% of first preference votes to Hinda Miller's 31.8%, Kevin Curley's 26.7%, and 2.1% other. The second round result was Kiss elected (48.6%) vs. Miller (40.7%), with the remainder of ballots expressing no preference between them.[5]

- Minneapolis, Minnesota, passed (65%) instant runoff voting in November 2006. Implementation is scheduled for the 2009 municipal elections[6].

- Pierce County, Washington passed (53%) instant runoff voting in November 2006 for implementation for most of its county offices in 2008[7].

- Takoma Park, Maryland adopted instant runoff voting for city council and mayoral elections in 2006. In January 2007, it held its first IRV election, to fill a city council vacancy, with a 3-way race, won with a majority of first preferences.[8] In November, 2007, the mayor ran unopposed, and, out of six ward seats on the ballot, one was contested. As write-in votes were less than 11% in any race, and the single contested seat was won with 66% first preference vote, runoff provisions were not exercised.[9]

- Oakland, California voters passed (69%) a measure in November 2006 to adopt IRV for its city offices, pending implementation[10].

- North Carolina, in July, 2006, adopted a pilot program for instant runoff voting for up to 10 cities in 2007 and up to 10 counties for 2008; to be monitored and reported to the 2007-2008 General Assembly.[11]. The city of Cary used IRV for municipal elections in October 2007.[12] The city of Hendersonville used a variant of IRV for municipal elections in November 2007, but runoff provisions were not needed.[13][14].

- Aspen, Colorado passed IRV (77%) in November 2007.[15]

- Sarasota, Florida passed IRV (78%) in November 2007.[16][17][18]

Application in absentee voting

Instant runoff voting and variations have been proposed as a solution to the logistical problems of overseas voting in states with runoff provisions. In the event of a runoff, election administrators would have to print new ballots, mail them to far-flung places, and receive them again. In the short window between the first election and the runoff, there often is not enough time. With a ranked instant runoff ballot, the votes of overseas citizens can count even if their first choice does not make the runoff, all on a single ballot. Arkansas, Louisiana and South Carolina all use this form of instant runoff voting on ballots for military and overseas voters.

Non-governmental organizations

A form of IRV is described in Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised, 10th edition. Pages 411-414 describe "preferential voting" as referring to "any of a number of voting methods by which, on a single ballot when there are more than two possible choices, the second or less-preferred choices of voters can be taken into account if no candidate or proposition attains a majority. While it is more complicated than other methods of voting in common use and is not a substitute for the normal procedure of repeated balloting until a majority is obtained, preferential voting is especially useful and fair in an election by mail if it is impractical to take more than one ballot. In such cases it makes possible a more representative result than under a rule that a plurality shall elect.... Preferential voting has many variations. One method is described ... by way of illustration." And then the sequential elimination technique of IRV is detailed. Robert's Rules continues: "The system of preferential voting just described should not be used in cases where it is possible to follow the normal procedure of repeated balloting until one candidate or proposition attains a majority. Although this type of preferential ballot is preferable to an election by plurality, it affords less freedom of choice than repeated balloting, because it denies voters the opportunity of basing their second or lesser choices on the results of earlier ballots, and because the candidate or proposition in last place is automatically eliminated and may thus be prevented from becoming a compromise choice."

Instant runoff voting has been adopted by various private and non-profit associations, such as the American Political Science Association, which provides in its constitution for electing its national President by mail if the election is contested, and, if there are three candidates or more, for the "alternative vote system" to be used; however, no election on record for that Association's President has been contested, thus IRV has not actually been used.[19].

Numerous college and university student governments have also adopted and use IRV. A list of such colleges and universities is available at the IRV advocacy organization FairVote.

Similar systems

Bucklin Voting also involves ranking candidates, and proceeds in rounds, but uses a different method of treating alternative votes in which a lower choice candidate can count against your higher choice candidate. If there is no majority winner in a Bucklin count, any second choices indicated by voters are added to the totals of all first choices. Bucklin was used in several states in the United States in the early part of the twentieth century. In the Duluth, Minnesota implementation, the third rank votes could be for as many candidates as desired, but the first two ranks allowed votes for one candidate only.

Runoff-voting

The term instant runoff voting is derived from the name of a class of voting systems called runoff voting. In runoff voting voters do not rank candidates in order of preference on a single ballot. Instead a similar effect is achieved by using multiple rounds of voting. The simplest form of runoff voting is the two round system. Under the two round system voters vote for only one candidate but, if no candidate receives an overall majority of votes, another round of voting is held from which all but the two candidates with most votes are excluded.

Runoff voting differs from IRV in a number of ways. The two round system can produce different results due to the fact that it uses a different rule for eliminations, excluding all but two candidates after just one round, rather than gradually eliminating candidates over a series of rounds. However all forms of runoff voting differ from IRV in that voters can change their preferences as they go along, using the results of each round to influence their decision. This is not possible in IRV, as participants vote only once, and this prohibits certain forms of tactical voting which can be prevalent in 'standard' runoff voting.

A closer system to IRV is the exhaustive ballot. In this system -- one familiar to American fans of the television show American Idol -- only one candidate is eliminated after each round, and many rounds of voting are used, rather than just two. [20] Because holding many rounds of voting on separate days is generally expensive, the exhaustive ballot is not used for large scale, public elections. Instant runoff voting is so named because it achieves a similar effect to runoff voting but it is necessary for voters to vote only once. The result can be found 'instantly' rather than after several separate votes.

Contingent vote

The contingent vote, also known as Top-two IRV, or batch-style, is the same as IRV except that all but the two candidates with most votes are eliminated after the first round; the count therefore only ever has two rounds. This differs from the 'two round' runoff voting system described above in that only one round of voting is conducted. The two rounds of counting therefore both take place after voting has finished. Two particular variants of the contingent vote differ from IRV in a further way. Under the forms of the contingent vote used in Sri Lanka, and the elections for London Mayor in the United Kingdom, voters are not permitted to rank all of the candidates, but only a certain maximum number. Under the variant used in London, called the supplementary vote, voters are only permitted to express a first and a second preference. Under the Sri Lankan form of the contingent vote voters are only permitted to rank three candidates. The supplementary vote is used for mayoral elections while the Sri Lankan contingent vote is used to elect the President of Sri Lanka.

While superficially similar to IRV these systems can produce different results. If, as occurs under all forms of the contingent vote, more than one candidate is excluded after the first count, a candidate might be eliminated who would have gone on to win the election under IRV. If voters are restricted to a maximum number of preferences then it is easier for their vote to become exhausted. This encourages voters to vote tactically, by giving at least one of their limited preferences to a candidate who is likely to win.

Conversely, a practical benefit of the 'contingent vote' counting process is expediency and confidence in the result with only two rounds. Most apparent in smaller elections, like with under 100 ballots among a dozen choices, confidence can be lost in a bottom-up elimination due to cumbersome ties on the bottom (or near ties affected by counting errors). Frequent and even multiple use of tie-breaking rules in one election will leave uncomfortable doubts over whether the winner might have changed if a recount was performed.

Practical implications

Instant runoff voting is more complex, both in terms of casting votes and counting them, than simpler systems such as 'first-past-the-post' plurality. Voters have the power to rank candidates in order of choice rather than merely write an 'x' beside a single candidate. Changing from plurality to IRV may therefore require the replacement of voting machinery, although several nations count ballot by hand.

IRV has been implemented in cities using optical scan machines, as in San Francisco (CA) and Burlington (VT). A hand count also is possible under IRV and is the method used in most non-American jurisdictions; however it is usually more time-consuming than a quick plurality count, and may need to occur over a number of rounds. It is claimed that IRV is less expensive than runoff voting because it is only necessary for voters to go to the polls once; however, the comparative expense would depend on how often runoffs were needed. IRV may also be less likely to induce voter fatigue, and exit polls indicate voters prefer IRV over two-round runoffs[21].

Under IRV, unlike some other preferential systems, the record of votes cast in a particular area cannot be conveniently summarized for transfer to a central location in which they can be counted. If areas were to report the number of votes cast for each possible order of candidates where all voters were required to vote for all candidates, as in the examples above, the permutations can be very large as the number of possible orders is equal to the factorial of the number of candidates. Three candidates would produce only six combinations but five candidates would produce 120 and ten candidates 3.6 million. But the voters do not have to vote for all candidates. So three candidates actually produces 16 possible choices (i.e., abstain, A, B, C, AB, BA, AC, CA, BC, CB, ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, CBA). This unwieldiness could prolong the counting procedure, provide more opportunities for undetected tampering than in more easily summable methods, and make recounts more costly. What happens in practice in Australia is a simplified count is sent through to the central location on the night with the actual ballot papers transported securely to the central location for the final count. In Ireland's presidential race, there are several dozen counting centers around the nation. Each center reports its totals for each candidate and receives instructions from the central office about which candidate or candidates to eliminate in the next round of counting.

Effect on parties and candidates

Unlike some other preferential voting systems, IRV puts particular value on a voter's first choice; a candidate with weak first choice support is unlikely to win even if ranked relatively well on many voters' ballots.

In Australia, the only nation with a long record of using IRV for the election of legislative bodies, IRV produces representation very similar to those produced by the plurality system, with a two party system in parliament similar to those found in many countries that use plurality. In the November 2007 elections, at least four candidates ran in every constituency, with an average of seven, but every constituency was won with an absolute majority of votes. </ref>[8]</ref>

Where preferential voting is used for the election of an assembly or council, parties and candidates often advise their supporters on how to use their lower preferences. As noted above, in Australia parties even issue 'how-to-vote' cards to the electorate before polling day, and Australia's requirement that voters must rank all candidates contributes to some voters using them. These kinds of recommendations can increase the influence of party leaderships and lead to a form of pre-election bargaining, in which smaller parties bid to have key planks of their platforms included in those of the major parties by means of 'preference deals'.

IRV is an election method designed for single seat elections. Therefore, like other single seat methods, if used to elect a council or legislature it will not produce proportional representation (PR). This means that it is likely to lead to the representation of a small number of larger parties in an assembly, rather than a proliferation of small parties. Under a parliamentary system it is more likely to produce single party governments than are PR systems, which tend to produce coalition governments. While IRV is designed to ensure that each individual candidate elected is supported by a majority of those in his or her constituency, if used to elect an assembly it does not ensure this result on a national level. As in other non-PR systems the party or coalition that wins a majority of seats will often not have the support of an overall majority of voters across the nation.

Majoritarianism and consensus

The intention of IRV is that the winning candidate will have the support of a majority of voters. It is often intended as an improvement on the 'First Past the Post' (plurality) voting system. Under 'First Past the Post' the candidate with most votes (a plurality) wins, even if they do not have a majority (more than half) of votes (unless election rules require a runoff under that condition). IRV attempts to address this problem by eliminating candidates one at a time, until one has a majority.

IRV is most suited to elections in which there can be only one winner, such as a mayor or governor. Many election reformers do not advocate IRV for legislative bodies or city councils that are intended to represent both majorities and minorities (in appropriate proportions).[[9]] As with any winner-take-all election method, IRV can result in a shut-out of minority represenation. Gerrymandering of single seat districts can also result in minorities gaining majority control of a legislative body, with IRV or any other winner-take-all election method.

The majority obtained by the winner of an IRV election is not always a majority of valid ballots cast, but rather a majority of ballots that indicated a preference between the runoff finalists. There are two possible reasons for this "majority failure": First, as in a common plurality or two-election runoff system, there may be a compromise candidate who is preferred by most voters to the actual winner, but whose lack of first choice support meant the candidate did not make it into the final runoff. Secondly, exhausted ballots, those with no votes on them for any remaining candidate, can result in the IRV winner not having received a vote from a majority of voters, but only a majority of votes from remaining ballots.

Critics of IRV argue that a candidate can only claim to have majority support by being the 'Condorcet winner'—that is, the candidate voters prefer to every other candidate when compared to them one at a time. Defenders argue that first and other higher preferences are more important than lower preferences, and point out that the Condorcet winner may be a candidate with no first choices.

Because of the value it puts in first choice support, IRV may be less likely to elect centrist candidates than some other preferential systems, such as a Condorcet method. For this reason it can be considered a less consensual system than these alternatives. Some IRV supporters consider this a strength, because a candidate with the enthusiastic support of many voters may be preferable to an allegedly mediocre compromise candidate, while still being acceptable to a majority of voters.

Tactical voting

Instant runoff voting reduces the possibility of tactical voting by reducing the spoiler effect in cases where there are two major candidates and one or more minor candidates.[22] Under the plurality ("first past the post") voting system, voters are encouraged to vote tactically by voting only for one of the two major candidates, because a vote for any other candidate is unlikely to affect the result.[23]

Is IRV better than other systems?

In the U.S., there is extensive debate about the merits of IRV compared to existing plurality voting and two-round systems, and also to other possible reforms. Below are some of the arguments used in the IRV debate, in comparison to existing plurality, actual runoff systems, and other voting methods. Some of these arguments may be false or otherwise misleading.

Pros

Proponents of IRV argue or allege that it:

- reduces the spoiler effect of plurality voting;[24]

- is simple and easy for voters;[25]

- encourages sincere voting and reduces the need for tactical voting;[22][23]

- when compared with the two-round system:

- reduces negative campaigning, by the incentive for candidates in receiving second and third choice votes;[27] and

- helps third parties gain traction by reducing the effect of vote splitting.[28]

Cons

Critics of IRV argue or allege that the system:

- does not eliminate the spoiler effect by virtue of failing the monotonicity criterion;[29]

- can reward, under some conditions, insincere voting;[30]

- does not guarantee election of a true majority winner due to exhausted ballots;[31]

- can eliminate a compromise candidate who could be preferred by a majority over the IRV winner;[32]

- is more expensive to count than Plurality voting or other systems,[33] requiring changes to ballots or voting equipment;[34]

- shows no evidence that negative campaigning is reduced;[35]

- takes more effort for voters compared to some other systems;[36]

- will result in more spoiled ballots;[37] and

- doesn't give voters a second chance to re-evaluate candidates as with an actual runoff.

Evaluation by criteria

Scholars of electoral systems often compare them using mathematically-defined voting system criteria, the value of some of which is controversial. Some of the criteria are considered by Arrow's Theorem and the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem, which assume that voters rank in a complete strict (exclusive) preference order, among other assumptions that do not hold for all methods. For methods such as IRV which use purely ranked preferences, satisfying all of those assumptions and criteria is impossible, as they are mutually exclusive.

- IRV passes the majority criterion, the later-no-harm criterion, the mutual majority criterion, the Condorcet loser criterion and, if the right tie-breaker method is used, the independence of clones criterion.

- IRV fails the monotonicity criterion, consistency criterion, the Condorcet criterion, the participation criterion, reversal symmetry, and the independence of irrelevant alternatives criterion [38].

See also

- Australian electoral system

- Ballot Access News for occasional related news in the United States

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- Electoral systems of the Australian states and territories

- Table of voting systems by nation

References

- ^ Australian Electoral Commission [1]

- ^ San Francisco Adopts Instant Runoff Elections, Richard Gonzales, National Public Radio

- ^ http://dailytribune.com/stories/110304/loc_electbox03001.shtml

- ^ Instant Runoff Voting Makes Advances November 2, Howard Ditkoff, Independent Progressive Politics Network

- ^ Burlington IRV election results

- ^ Measure to overhaul municipal races passes, Terry Collins, Star Tribune, November 8, 2006.

- ^ Pierce County Auditor.

- ^ Takoma Park's New Vote System Makes Debut, Miranda S. Spivack, Washington Post, Feb. 8, 2007.

- ^ Official Results

- ^ Offbeat and practical issues taken up around Bay Area, Heather Knight, San Francisco Chronicle, Nov. 8, 2006.

- ^ House Bill 1024, General Assembly of North Carolina, Session 2005.

- ^ Asheville Citizen-Times.

- ^ [2] Blue Ridge Now election results

- ^ [3] Blue Ridge Now poll of voters

- ^ Aspen Times Weekly

- ^ Sarasota ordinance

- ^ Votes could make Sarasota a model of election reform

- ^ [4]

- ^ Business Meeting Minutes

- ^ Glossary: Exhaustive ballot

- ^ San Francisco exit poll by San Francisco University

- ^ a b John J. Bartholdi III, James B. Orlin (1991) "Single transferable vote resists strategic voting," Social Choice and Welfare, vol. 8, p. 341-354

- ^ a b John R. Chamberlin (1985) "An investigation into the relative manipulability of four voting systems" Behavioral Science, vol. 30, p. 195-203

- ^ Correcting the Spoiler Effect, FairVote.

- ^ BerkeleyMeasure I Arguments For

- ^ Say yes to Instant Runoff Voting, Pasadena Weekly, Nov. 16, 2006.

- ^ a b Frequently Asked Questions About Instant Runoff Voting

- ^ Vote yes for instant runoff, The Minnesota Daily, Oct. 31, 2006.

- ^ http://wiki.electorama.com/wiki/Instant-runoff_voting#Flaws_of_IRV

- ^ http://wiki.electorama.com/wiki/Instant-runoff_voting#Flaws_of_IRV

- ^ VOTE NO ON MEASURE I. Do Not Give City Council a BLANK CHECK To Choose Any Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) System, Ballot Measure Info, Berkeley, California, Mar. 2, 2004.

- ^ [5]

- ^ Rangevoting.org:"Total cost of switching: zero."

- ^ Instant-runoff voting urged for Alameda County, Ian Hoffman, Oakland Tribune, Apr. 21, 2005.

- ^ *"Instant Runoff Voting Not Meeting Expectations"

- ^ Candidate ranking system of voting on Ferndale ballot, Michael P. McConnell, Daily Tribune, Oct. 25, 2004.

- ^ Measure I Arguments Against

- ^ David Austen-Smith and Jeffrey Banks, "Monotonicity in Electoral Systems," American Political Science Review, Vol 85, No 2 (Jun. 1991)

External links

- Advocacy organisations

- Instant Runoff Voting at FairVote

- Political Reform Program at New America Foundation

- League of Women Voters of Vermont

- Better Ballot Campaign IRV for Minneapolis (Hosted by FairVote Minnesota)

- instantrunoff.com, by the Midwest Democracy Center [10]

- FIRV (Ferndale, Michigan for Instant Runoff Voting)

- Californians for Electoral Reform

- California IRV Coalition

- US PIRG

- Coalition for Instant Runoff Voting in Florida

- Green Party (United States)

- History of Use in Ann Arbor

- Minnesota Council of Nonprofits

- Democracy North Carolina

- Opposition positions

- "The Problem with Instant Runoff Voting"

- IRV page at the Center for Range Voting

- Flaws in IRV compared to ranked pairs

- Minnesota Voters Alliance

- Straight Talk On So-Called "Instant Runoff Voting" or Why the "Cure" Is as Deadly as the "Disease"

- Instant Runnoff Voting Report Values and Risks Report by the N.C. Coalition for Verified Voting

- Libertarian Reform Caucus "Anyone for a Bullet in the Foot? Instant Runoff!"

- Instant Runoff Voting Facts Verses Fiction

- Analysis

- Nonmonotonicity in AV Article by Eivind Stensholt.

- Comparison with Condorcet Voting by Blake Cretney

- Voting methods: tutorial and essays by James Green-Armytage (for IRV, see e.g. 1 2 3 4 5)

- A Handbook of Electoral System Design from International IDEA

- Electoral Design Reference Materials from the ACE Project

- ACE Electoral Knowledge Network Expert site providing encyclopedia on Electoral Systems and Management, country by country data, a library of electoral materials, latest election news, the opportunity to submit questions to a network of electoral experts, and a forum to discuss all of the above

- Simulation Of Various Voting Models for Close Elections Article by Brian Olson.

- Preferential voting in Australia

- Chuck Herrin, certified IT certificaton specialist "I think that IRV is a fabulous goal, long term....[however] IRV introduces a more confusing system in terms of auditability and security"

- IRV in practice

- [11] San Francisco Department of Elections on its IRV elections

- [12] City of Burlington, Vermont on its IRV elections

- [13] Blog focused on implementation of IRV in Pierce County, Washington

- [14] City of Takoma Park, Maryland on its IRV elections

- [15] City of Cary, NC

- [16]City of Hendersonville, NC

- Examples

- IRV Poll For 2008 U.S. Democratic Party Nominee at ChoiceRanker.com (formerly Indaba.org)

- IRV Poll For 2008 U.S. Democratic Party Nominee at demochoice.org

- IRV poll for U.S. President, 2004 by the Independence Party of Minnesota

- OpenSTV -- Open source software for computing IRV and STV

- Favourite Futurama Character Poll

- ¿Quién fué el preferido en la simulación de Votación Presidencial por el Sistema de Rondas Simultánes? in Guatemala

- IRV Flash Animations