Psychoactive drug: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 208: | Line 208: | ||

*[http://lycaeum.org/ The Lycæum] – Lycaeum Synaesthesia (similar website) |

*[http://lycaeum.org/ The Lycæum] – Lycaeum Synaesthesia (similar website) |

||

*[http://www.tccwiki.com/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page TCCWiki] A free collaborative drug information project that anyone can edit |

*[http://www.tccwiki.com/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page TCCWiki] A free collaborative drug information project that anyone can edit |

||

* [http://www.quihn.org.au Fact sheets and harm reduction strategies about psychoactive drugs] |

|||

Revision as of 23:38, 19 June 2006

A psychoactive drug or psychotropic substance is a chemical that alters brain function, resulting in temporary changes in perception, mood, consciousness, or behavior. Such drugs are often used in recreational drug use and as entheogens for spiritual purposes, as well as in medication, especially for treating neurological and psychiatric illnesses.

Many of these substances (especially the stimulants and depressants) can be habit-forming, causing chemical dependency and often leading to substance abuse. Conversely, others (namely the psychedelics) can help to treat and even cure such addictions.

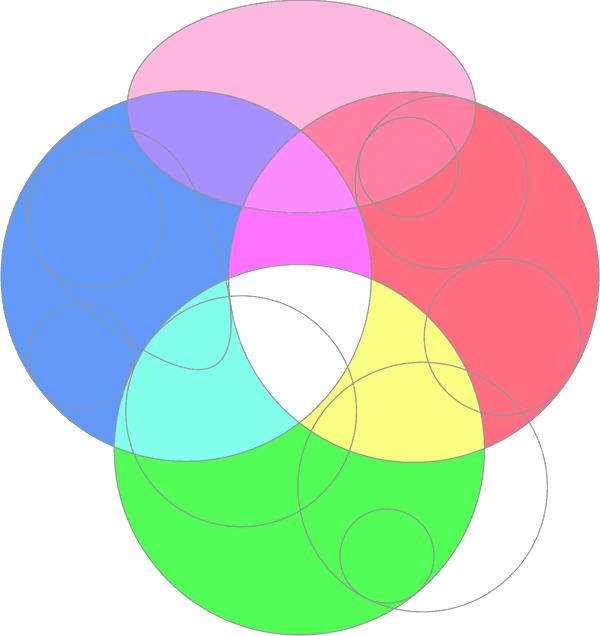

Psychoactive drug chart

The following Venn diagram attempts to organize and provide a basic overview of the most common psychoactive drugs into intersecting groups and subgroups based upon pharmacological classification and method of action.[1][2] Items within each subgroup are close to those of most similar action, and also follow a general placement in accordance with the legend below the diagram. Primary intersections are represented via color mixing. (Note: this is a work in progress. Please discuss errors, changes and suggestions on the talk page).

Legend

- Blue: Stimulants generally increase in potency to the upper left.

- Red: Depressants generally increase in potency to the lower right.

- Green: "Hallucinogens" are psychedelic to the left, dissociative to the right, generally less predictable down and to the right, and generally more potent towards the bottom.

- Pink hue: The so called "antipsychotics". A new and controversial addition to the chart.

Sub-sections

- White: Overlap of all three main sections (Stimulants, Depressants and Hallucinogens) — Example: cannabis exhibits effects of all three sections.

- Magenta (purple): Overlap of Stimulants (Blue) and Depressants (Red) — Example: nicotine and SSRIs exhibit effects of both.

- Cyan (light blue): Overlap of Stimulants (Blue) and Psychedelic hallucinogens (Green) — Primary psychedelics exhibit a stimulant effect

- Yellow : Overlap of Depressants (Red) and Dissociative hallucinogens (Green) — Primary dissociatives exhibit a depressant effect

A brief history of drug use

Drug use is not a new phenomenon by any means. There is archaeological evidence of the use of psychoactive substances dating back at least 10,000 years, and historical evidence of cultural use over the past 5,000 years.[3]

While medicinal use plays a very large role, it has been suggested that the urge to alter one's consciousness is as primary as the drive to satiate thirst, hunger or sexual desire.[4]

Some may point a finger to marketing, availability or the pressures of modern life as to why humans use so many psychoactives in their daily lives, but one only has to look back at history, or even to children with their desire for spinning, swinging, sliding amongst other activities to see that the drive to alter one's state of mind is universal.[4]

This relationship is not limited to humans. A surprising number of animals consume different psychoactive plants and animals, berries and even fermented fruit, clearly becoming intoxicated. Traditional legends of sacred plants often contain references to animals that introduced man to their use.[5]

Biology suggests an evolutionary connection between psychoactive plants and animals, as to why these chemicals and their receptors exist within the nervous system.[6]

Other psychoactive drugs

- In a broader sense also:

Ways psychoactive drugs affect the brain

There are many ways in which psychoactive drugs can affect the brain (see neuropsychopharmacology). While some drugs affect neurons presynaptically, others act postsynaptically and some drugs don't even attack the synapse, working on neural axons instead.[citation needed] Here is a general breakdown of the ways psychoactive drugs can work.

- Prevent The Action Potential From Starting

- Lidocaine, TTX (they bind to voltage-gated sodium channels, so no action potential begins even when a generator potential passes threshold)

- Neurotransmitter Synthesis

- Increase - L-Dopa, tryptophan, choline (precursors)

- Decrease - PCPA (inhibits synthesis of 5HT)

- Causes increased sensitivity to the five senses, due to an increasing number of signals being sent to the brain.

- Neurotransmitter Packaging

- Increase - MAO Inhibitors

- Decreasing - Resperine (pokes holes in the synaptic vesicles of catecholamines)

- Neurotransmitter Release

- Increase - Black Widow Spider (Ach)

- Decrease - Botulinum Toxin (Ach), Tetanus (GABA)

- Agonists - Mimic the original NTs and activate the receptors

- Muscuraine, Nicotine (Ach)

- AMDA, NMDA (Glu)

- Alcohol, Benzodiazepines (GABA)

- Antagonists - Bind to the receptor sites and block activation

- Atropine, Curare (Ach)

- PCP (Glu)

- Prevent Ach Breakdown -

- Insecticides, Nerve Gas

- Prevent Reuptake

- Cocaine (DA), Amphetamines (E)

- Tricyclics, SSRIs

- based on information taught in NSC 201, Vanderbilt University [citation needed]

Philosophy and Morality of psychoactive drugs

For thousands of years, people have studied psychoactive drugs, both by observation and ingestion. However, humanity remains bitterly divided regarding psychoactive drugs, and their value and use has long been an issue of major philosophical and moral contention, even to the point of war (the Opium Wars being a prime example of a war being fought over psychoactives). A majority of youths and adults consume one or more psychoactive drugs[citation needed]. In the West, the most common by numbers of users are caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine, in that order. Most people accept restrictions on some and the prohibition of others, especially the "hard" drugs, which are generally illegal in most countries.

Because so many consumers want to reduce or eliminate their own use, many professionals, self-help groups, and businesses specialize in that field, with varying degrees of success. Many parents attempt to influence the actions and choices of their children.

Debate continues over whether each psychoactive drug being considered is or is not spiritual, sinful, therapeutic, poisonous, ethical, immoral, effective, risky, responsible, recreational, a weapon to use against enemies, a boost to the economy, etc. These attitudes can often be deeply rooted in philosophical and/or religious beliefs, making it difficult to reach consensus or agreement on the proper moral and philosophical stance regarding psychoactive drugs. A major point of contention regards the role of government, whether it should, in respect to each drug, remain neutral, make use safer, educate for abstention, educate for moderation, regulate trade, require a prescription, restrict promotion, prohibit altogether, alter penalties, change enforcement, and so on.

See also

- Antipsychotics

- Stimulants

- Depressants

- Hallucinogens

- Entheogens

- Medication

- Recreational drug use

- Drug addiction

- Demand reduction

- Freedom of thought

- Substance abuse

- Poly drug use

- List of street names of drugs

- Arguments for and against drug prohibition

- Neuropsychopharmacology

- Psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants

References

- ^ William A. McKim (2002). Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5th Edition). Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 0130481181.

- ^ "Information on Drugs of Abuse". Commonly Abused Drug Chart. Retrieved December 27th.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ M.D. Merlin. "Archaeological Evidence for the Tradition of Psychoactive Plant Use in the Old World". Economic Botany. 57 (3): 295–323.

- ^ a b Weil, Dr. Andrew (2004). The Natural Mind : A Revolutionary Approach to the Drug Problem (Revised edition). Houghton Mifflin. p. 15. ISBN 0618465138.

- ^ Samorini, Giorgio (2002). Animals And Psychedelics: The Natural World & The Instinct To Alter Consciousness. Park Street Press. ISBN 0892819863.

- ^ Albert, David Bruce, Jr. (1993). "Event Horizons of the Psyche". Retrieved February 2nd.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Siegel, Ronald K (2005). Intoxication: The Universal Drive for Mind-Altering Substances. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont. ISBN 1-59477-069-7.(paperback edition) Note: new ISBN comes in 1 January 2007 and is 978-1-59477-069-2

External links

- Erowid – Extensive portal primarily relating to psychoactive drugs (Wikipedia article about the website – Erowid)

- The Lycæum – Lycaeum Synaesthesia (similar website)

- TCCWiki A free collaborative drug information project that anyone can edit

- Fact sheets and harm reduction strategies about psychoactive drugs