Religion in Norway: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

I removed a part of the article which said the Islam was the 3rd largest religion in Norway and such statement was unfounded and had no citations. |

Added image. Tag: Mobile edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

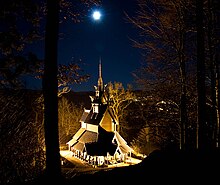

[[File:Vinterdomen.jpg|thumb|340px|[[Nidaros Cathedral]], the largest church in Norway.]] |

[[File:Vinterdomen.jpg|thumb|340px|[[Nidaros Cathedral]], the largest church in Norway.]] |

||

[[File:World Islamic Mission 1.jpg|thumb|340px|[[World Islamic Mission]], mosque in Oslo]] |

|||

{{Norwegian-people}} |

{{Norwegian-people}} |

||

Revision as of 16:16, 11 June 2014

| Part of a series on |

| Norwegians |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Diaspora |

| Other |

| Norwegian Portal |

Nominal religion in Norway is mostly Evangelical Lutheran with 77% of the population belonging to the state Evangelical Lutheran Church of Norway.[1] Early Norwegians, like all of the people of Scandinavia, were adherents of Norse paganism; the Sámi having a shamanistic religion.[2] Due to the efforts of Christian missionaries, Norway was gradually Christianized in a process starting at approximately 1000 and substantially finished by 1150. Prior to the Reformation, Norwegians were part of the Catholic Church with the conversion to Protestantism commencing in 1536.

In modern times, Norway – like many European countries – has seen a great decline in religiosity, at least among non-immigrant Norwegian endemics,[citation needed] and most Norwegians are irreligious: atheism and agnosticism are the most common metaphysical views according to Zuckerman.

Christian Orthodoxy is the fastest-growing religious tradition in Norway with a rate of 231.1% compared to Islam's 64.3% from 2000 to 2009.[3]

According to the most recent Eurobarometer Poll 2010,[4]

- 22% of Norwegian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God".

- 44% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force".

- 29% answered that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".

- 5% answered that they "do not know".

Phil Zuckerman, an Associate Professor of Sociology at Pitzer College estimates atheism rates in Norway as ranging from 31 to 72%, based on various studies.[5]

Norse religion

Norse religion developed from the common mythology of the Germanic people. Scandinavian mythology and the relative importance of gods and heroes developed slowly. Thus, the cult of Odin in Norway probably spread from Western Germany not long before they were written down. Gods shown as minor gods such as Ullr, the fertility god Njord and Heimdall are likely to be older gods in Norway who lost popularity. Other gods (or aesir, as they were called) worth mentioning are the thunder-god Thor and the love-goddess Freya.

Most information about Scandinavian mythology is contained in the old Norse literature including Norwegian literature, the Eddas and later sagas. Other information comes from the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus with fragments of legends preserved in old inscriptions. Unfortunately, we know relatively little about old religious practices in Norway or elsewhere as most of the knowledge was lost in the gradual Christianisation.

Due to nationalistic movements in the late 18th century, Norwegian scholars found renewed interest for Norse religion, translating many of the myths to Danish (the written language in Norway at the time) and tried to use it to create a common Norwegian culture. But Christianity was too deeply rooted in the society to accept such Paganism, and it only resulted in popularized legends. Nowadays, a revival of the Old Norse religion, called Åsatru ("Faith of the Aesir") seeks to reconstruct the pre-Christian faith practiced in the Viking Age.

Sámi religion

The Sámi followed a shamanistic religion based on nature worship. The Sámi pantheon consisted of four general gods the Mother, the Father, the Son and the Daughter (Radienacca, Radienacce, Radienkiedde and Radienneida). There was also a god of fertility, fire and thunder Horagalles, the sun goddess Beive and the moon goddess Manno as well as the goddess of death Jabemeahkka.

Like many pagan religions, the Sámi saw life as a circular process of life, death and rebirth. The shaman was called a Noaide and the traditions were passed on between families with an ageing Noaide training a relative to take his or her place after he or she dies. Training went on as long as the Noaide lived but the pupil had to prove his or her skills before a group of Noaidi before being eligible to become a fully fledged shaman at the death of his or her mentor.

The Norwegian church undertook a campaign to Christianise the Sámi in the 16th and 17th century with most of the sources being missionaries. While the vast majority of the Sámi in Norway have been Christianised, some of them still follow their traditional faith and some Noaidi are still practising their ancient religion. Sami people are often more religious than Norwegians.

Christianity

From Conversion to Reformation

The conversion of Norway to Christianity began in 1000 . The raids on the British isles and on the Frankish kingdoms had brought the Vikings in touch with Christianity. Haakon the Good of Norway who had grown up in England tried to introduce Christianity in the mid-10th century, but had met resistance from pagan leaders and soon abandoned the idea.

Anglo-Saxon missionaries from England and Germany had tried to convert Norwegians to Christianity but only had limited success. However, they succeeded in converting Olaf I of Norway to Christianity. Olaf II of Norway (later Saint Olaf) had more success in his attempts to convert the population with many Norwegians converting in the process, and he is credited with Christianizing Norway.

The Christians in Norway often established churches or other holy sites at places that had previously been sacred under the Norse religion. The spread of conversion can be measured by burial sites as Pagans were buried with grave goods while Christians weren't. Christianity had become well established in Norway by the middle of the 11th century and had become dominant by the middle of the 12th century. Stave churches were built of wood without the use of nails in the 13th century.[6]

From Reformation to 1964

The Norwegians were Catholic until the Danish king Christian III of Denmark ordered Denmark to convert to Lutheranism in 1536 and as Norway was then ruled by Denmark, the Norwegians converted as well. The Danish Church Ordinance was introduced in 1537 and a Norwegian Church Council officially adopted Lutheranism in 1539. Monasteries were dissolved and church property confiscated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Norway established and funded by the state. Bishops still adhering to Catholicism were deposed with Olav, Archbishop of Nidaros fleeing the country in 1537 and another bishop dying in prison in 1542. Catholicism held on remote parts of Norway for another couple of decades, although eventually the remaining Catholics converted or fled, to the Netherlands in particular. Many pastors were replaced with Danes and Norwegian clergy being trained at the University of Copenhagen as Norway did not have a university. The Danish translation of the Bible was used as were Danish catechisms and hymns. The use of Danish in religious ceremonies had a strong influence on the development of the Norwegian language.

The church undertook a program to convert the Sámi in the 16th and 17th century with the program being largely successful. The University of Oslo was established in 1811 allowing priests to train in Norway. The Norwegian Constitution of 1814 did not grant religious freedom as it stated that Jews and Jesuits were denied entrance in Norway. Moreover, adherence to Evangelical Lutheran Christianity was compulsory, and so was church attendance. A ban on lay preaching was lifted in 1842, allowing several free church movements and a strong lay movement being established in the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Three years later, the so-called Dissenter Law came into effect, allowing other Christian congregations to establish in Norway. Atheism became allowed as well, and the ban on Judaism was lifted in 1851. Monasticism and Jesuites were allowed starting in 1897 and 1956 respectively.

The Norwegian Constitution was amended in 1964 allowing freedom of religion. Exceptions are the Norwegian royal family, who are required by the Constitution to be Lutherans. Furthermore, at least one half of the Government must belong to the state church.

Church pastors were active in the Norwegian resistance movement during World War II. The church was also active in the moral debate which arose in the 1950s.

Islam

Islam is the largest minority religion in Norway with over 2% of the population. In 2007, government statistics registered 79,068 members of Islamic congregations in Norway, about 10% more than in 2006.[7] 56% lived in the counties of Oslo and Akershus.[8] Scholarly estimates from 2005 regarding the number of people of Islamic background in Norway vary between 120,000 and 150,000.[9] In the end of the 1990s, Islam passed the Roman Catholic Church and Pentecostalism to become the largest minority religion in Norway, provided Islam is seen as one united grouping, as there are different denominations in existence, such as Sunni, Shia and Ahmadiyya. In 2004, the registered Muslims were members of 92 different congregations. Forty of these were based in Oslo or Akershus counties.

Judaism

There were never many Jews in Norway. Although there are no indications of active persecution, Jews were banned from entering and residing in the dual monarchy of Denmark-Norway for long periods of time. After the split with Denmark in 1814, the new Norwegian Constitution included a notorious paragraph that banned Jews and Jesuits from entering the realm. The paragraph, which was abolished with regard to Jews in 1851 after strong political debate, appears to have been primarily aimed at the Jewish Messianic revival movements in Eastern Europe at the time, since the Sephardi and Western European Jews in many cases seem to have been exempted.[citation needed]

Shechita, Jewish kosher slaughter, has been banned in Norway since 1929,[10]

741 Norwegian Jews were murdered during the Nazi occupation of Norway during World War II, and in 1946 there were only 559 Jews registered living in Norway.

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith in Norway began with contact between traveling Scandinavians with early Persian believers of the Bahá'í Faith in the mid-to-late 19th century.[11] Bahá'ís first visited Scandinavia in the 1920s following `Abdu'l-Bahá's, then head of the religion, request outlining Norway among the countries to which Bahá'ís should pioneer[12] and the first Bahá'í to settle in Norway was Johanna Schubartt.[13] Following a period of more Bahá'í pioneers coming to the country, Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assemblies spread across Norway while the national community eventually formed a Bahá'í National Spiritual Assembly in 1962.[14] There are currently around 1000 Bahá'ís in the country.[15]

Religion in Norway today

The Evangelical Lutheran Church is still established and administered through a Government department. There is, however, an ever ongoing political debate on separation of church and state.[16] The state also supports religious aid organisations such as Norwegian Church Aid financially. Bishops are formally nominated by the Norwegian Monarch,[17] who is the head of the church, and clerical salaries and pensions regulated by law. Clergy train in the theological faculties of the University of Oslo and the University of Tromsø, as well as Misjonshøgskolen (School of Mission and Theology) in Stavanger and Menighetsfakultetet (MF Norwegian School of Theology) in Oslo. Menighetsfakultetet is by far the most important educational institution for the Norwegian clergy. Men and women can both become members of the clergy of the church. The church has two sacraments namely Baptism and Holy Communion.

In Norway, 77% of the population are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church as compared to 96% in the 1960s.[1] Kevin Boyle's 1997 global study of freedom of religion states that "Most members of the state church are not active adherents, except for the rituals of birth, confirmation, weddings, and burials. Some 3 per cent on average attend church on Sunday and 10 per cent on average attend church every month."[18]

Approximately 9–10% are probably not members of any religious or philosophical communities, while 8.6% of the population are members of other religious or philosophical communities outside the Church of Norway.[19]

Other religious groups operate freely; Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs are present in very small numbers, together comprising less than 1 percent of the population.

In 2005, a survey conducted by Gallup International in sixty-five countries indicated that Norway was the least religious country in Western Europe, with 29% counting themselves as believing in a church or deity, 26% as being atheists, and 45% not being entirely certain.[20]

| Religion (in 2013)[21][22] | Members | Percent | Growth (2009–2013) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 4,161,220 | 82.4% | 1.9% |

| Lutheranism | 3,902,031 | 77.2% | 0.2% |

| Roman Catholic Church | 121,130 | 2.4% | 111.2% |

| Pentecostal congregations | 39,412 | 0.8% | −0.4% |

| Orthodox Church | 12,959 | 0.3% | 69.1% |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 12,049 | 0.2% | −19.5% |

| The Methodist Church in Norway | 10,715 | 0.2% | −2.4% |

| Baptists | 10,213 | 0.2% | 10% |

| Brunstad Christian Church (aka Smith's friends) | 7,259 | 0.1% | 7.1% |

| Seventh-day Adventist Church | 4,841 | 0.1% | −4.8% |

| Other Christianity | 40,611 | 0.8% | 7.1% |

| Non-Christian religions | 150,414 | 3.0% | 30.6% |

| Islam | 120,882 | 2.4% | 30.3% |

| Buddhism | 16,001 | 0.3% | 30.6% |

| Hinduism | 6,797 | 0.1% | 29.8% |

| Sikhism | 3,323 | 0.1% | 22.5% |

| Bahá'í Faith | 1,122 | 0.0% | 9.7% |

| Judaism | 788 | 0.0% | −1.9% |

| Other religions | 1,501 | 0.0% | 142.9% |

| Humanism | 86,061 | 1.7% | 6.1% |

| no affiliation or unknown | 653,580 | 12.9% | |

| Total | 5,051,275 | 100.0% | 5.3% |

-

A Hindu temple in Trondheim.

-

The synagogue in Oslo.

-

Orthodox church in Oslo.

-

Nor mosque in Oslo.

-

Khuong Viet Buddhist Temple in Oslo.

Religious education

In 2007, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in favor of Norwegian parents who had sued the Norwegian state. The case was about a subject in compulsory school, kristendomskunnskap med religions- og livssynsorientering (Teachings of Christianity with orientation about religion and philosophy), KRL. The applicants complained that the refusal to grant full exemption from KRL prevented them from ensuring that their children received an education in conformity with their atheist views and philosophical convictions. A few years earlier, in 2004, the UN Committee on Human Rights in Geneva had given its support to the parents.[23] In 2008 the subject was renamed to Religion, livssyn og etikk (Religion, philosophy and ethics).[24] The majority of this course is however still tied to Christianity. Philosophy and ethics are not properly introduced until after compulsory school. The largest Christian school in Norway has 1,400 pupils and 120 employees.[25] Kristne Friskolers Forbund is an interest group of approximately 130 Christian schools and colleges, including 12 Christian private schools.[26]

Religious media

See also

- Christianization of Scandinavia

- Islam in Norway

- Irreligion in Norway

- Judaism in Norway

- Norwegian Humanist Association

- Religion by country

- Religion in Europe

- Bible translations in Norway

Notes

- ^ a b Church of Norway, 2011 Statistisk Norway 19.5.2012

- ^ http://english.karasjok.kommune.no/document.aspx?uid=49&title=Pre-Christian+Religion

- ^ Statistics Norway

- ^ Biotechnology report 2010 p.383

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil (2006). "Atheism—Contemporary numbers and Practices". In Michael Martin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. Cambridge University Press –. pp. 47–50. ISBN 0-521-84270-0. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ Norway – Ecclesiastical organization (Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Bergen)

- ^ Table 1 Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance. Per 1.1. 2005– 2007. Numbers and per cent

- ^ Template:No icon Medlemmer i trus-og livssynssamfunn utanfor Den norske kyrkja

- ^ Template:No icon Islam i Norge

- ^ Johansen, Per Ola (1984). "Korstoget mot schächtningen". Oss selv nærmest (in Norwegian). Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag. p. 63. ISBN 82-05-15062-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ National Spiritual Assembly of Norway (2007–8). "Skandinavisk bahá'í historie". Official Website of the Bahá'ís of Norway. National Spiritual Assembly of Norway. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ `Abdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 43. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- ^ National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Norway (25 March 2008). "Johanna Schubarth". Official Website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Norway. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Norway. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ The Bahá'í Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Bahá'í Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- ^ Statistics Norway (2008). "Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance". Church of Norway and other religious and life stance communities. Statistics Norway. Retrieved 26 April 2008. [dead link]

- ^ See Church of Norway, current issues

- ^ "Monarch" is here the word that is used in the Norwegian constitution. But it is the Government that decides.[citation needed]

- ^ Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report (Routledge, 1997), page 351.

- ^ Statistics Norway, numbers from 2007

- ^ "Aftenposten: Vi tviler mer (17.02.06)". Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Statistics Norway – Church of Norway and other religious and philosophical communities

- ^ Church of Norway statistics are from 2012.

- ^ Human-Etisk Forbund – seier for humanistene – tap for staten Template:No icon

- ^ See the Norwegian Wikipedia: Kristendoms-, religions- og livssynskunnskap

- ^ Forside: Egill Danielsen Stiftelse

- ^ Kristne Friskolers Forbund

External references

- Official Norwegian site in the UK on Norwegian religion

- Statistics Norway: More members in religious and philosophical communities)

- The Church in Norwegian life

- BBC Ancient History article on Viking religion and their gradual conversion to Christianity

- Site on Viking religion

- Site on Sámi religious beliefs

- Site on Norwegian reformation

- Boise State University on Danish reformation

- Religious and philosophical communities, 1 January 2006