Hyatt Regency walkway collapse: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 205.174.116.6 (talk) to last revision by 2601:192:8801:91F7:EDDB:6A24:F2D5:F53E (TW) |

|||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

Construction began in |

Construction began in Mayghfhjghj 1978 on the 40-story [[Hyatt Regency Kansas City]]. There were numerous delays and setbacks, including the collapse of {{convert|2700|sqft|m2}} of the roof. Nonetheless, the hotel officially opened on July 1, 1980.<ref name="NYT">{{cite news |author=Staff |accessdate=July 17, 2019 |title=45 Killed at Hotel in Kansas City, Mo., as Walkways Fall |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/18/us/45-killed-at-hotel-in-kansas-city-mo-as-walkways-fall.html |newspaper=The New York Times |date=July 18, 1981 |issn=0362-4331 |via=NYTimes.com}}</ref> |

||

The hotel's lobby was one of its defining features, which incorporated a multi-story atrium spanned by elevated walkways suspended from the ceiling. These steel, glass, and concrete crossings connected the second, third, and fourth floors between the north and south wings. The walkways were approximately {{convert|120|ft|abbr=on}} long<ref name="nbs">{{cite web| title=Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse| author=National Bureau of Standards| date=May 1982| accessdate=February 17, 2018| publisher=US Department of Commerce| url=https://www.nist.gov/publications/investigation-kansas-city-hyatt-regency-walkways-collapse-nbs-bss-143?pub_id=908286}}</ref> and weighed approximately {{convert|64000|lb|kg|abbr=on}}.<ref name="kcpl">{{cite web| title=Hotel Horror| url=http://www.kchistory.org/week-kansas-city-history/hotel-horror | publisher=Kansas City Public Library| date= | accessdate=April 30, 2019}}</ref> The fourth-level walkway was directly above the second-level walkway. |

The hotel's lobby was one of its defining features, which incorporated a multi-story atrium spanned by elevated walkways suspended from the ceiling. These steel, glass, and concrete crossings connected the second, third, and fourth floors between the north and south wings. The walkways were approximately {{convert|120|ft|abbr=on}} long<ref name="nbs">{{cite web| title=Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse| author=National Bureau of Standards| date=May 1982| accessdate=February 17, 2018| publisher=US Department of Commerce| url=https://www.nist.gov/publications/investigation-kansas-city-hyatt-regency-walkways-collapse-nbs-bss-143?pub_id=908286}}</ref> and weighed approximately {{convert|64000|lb|kg|abbr=on}}.<ref name="kcpl">{{cite web| title=Hotel Horror| url=http://www.kchistory.org/week-kansas-city-history/hotel-horror | publisher=Kansas City Public Library| date= | accessdate=April 30, 2019}}</ref> The fourth-level walkway was directly above the second-level walkway. |

||

Revision as of 17:19, 28 August 2019

Locations of the second- and fourth-story walkways, which both collapsed into the lobby of the Hyatt Regency hotel | |

| Date | July 17, 1981 |

|---|---|

| Time | 19:05 CDT (UTC−5) |

| Location | Kansas City, Missouri |

| Coordinates | 39°05′06″N 94°34′48″W / 39.085°N 94.580°W |

| Cause | Structural overload resulting from design flaws[1] |

| Deaths | 114 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 216 |

On July 17, 1981, two walkways collapsed at the Hyatt Regency Kansas City hotel in Kansas City, Missouri, one directly above the other. They crashed onto a tea dance being held in the hotel's lobby, killing 114 and injuring 216.[2] It was the deadliest structural collapse in American history[3] until the collapse of the World Trade Center towers 20 years later.

Background

Construction began in Mayghfhjghj 1978 on the 40-story Hyatt Regency Kansas City. There were numerous delays and setbacks, including the collapse of 2,700 square feet (250 m2) of the roof. Nonetheless, the hotel officially opened on July 1, 1980.[4]

The hotel's lobby was one of its defining features, which incorporated a multi-story atrium spanned by elevated walkways suspended from the ceiling. These steel, glass, and concrete crossings connected the second, third, and fourth floors between the north and south wings. The walkways were approximately 120 ft (37 m) long[5] and weighed approximately 64,000 lb (29,000 kg).[6] The fourth-level walkway was directly above the second-level walkway.

Collapse

Approximately 1,600 people gathered in the atrium for a tea dance on the evening of Friday, July 17, 1981.[7] The second-level walkway held approximately 40 people at approximately 7:05 p.m., with more on the third and an additional 16 to 20 on the fourth.[5] The fourth-floor bridge was suspended directly over the second-floor bridge, with the third-floor walkway offset several yards from the others. Guests heard popping noises moments before the fourth-floor walkway dropped several inches, paused, then fell completely onto the second-floor walkway. Then both walkways fell to the lobby floor.[8]

They said "take what you want". I don't know if all those people got their equipment back. But no one has ever asked for an accounting and no one has ever submitted a bill.

—Deputy Fire Chief Arnett Williams, in reference to local construction sites providing tools and volunteers[9]

The rescue operation lasted 14 hours.[10] Survivors were buried beneath steel, concrete, and glass which the fire department's jacks could not move. Volunteers responded to an appeal and brought jacks, torches, compressors, jackhammers, concrete saws, and generators from construction companies and suppliers.[9] They also brought cranes and forced the booms through the lobby windows to lift debris.[11] Kansas City emergency medical director Joseph Waeckerle directed the effort.[2] The dead were taken to a ground floor exhibition area as a makeshift morgue,[12] and they used the hotel's driveway and front lawn as a triage area.[13] They instructed those who could walk to leave the hotel to simplify the rescue effort, and they gave morphine to those who were mortally injured.[8][14] Often, rescuers had to dismember bodies to reach survivors among the wreckage.[8] A surgeon had to amputate one victim's crushed leg with a chainsaw.[15]

Water flooded the lobby from the hotel's ruptured sprinkler system and put trapped survivors at risk of drowning. Property valuer Mark Williams spent more than nine hours pinned underneath the lower skywalk with both legs dislocated, and he nearly drowned before the water was shut off. Visibility was poor because of dust and because the power had been cut to prevent fires.[16][11] A total of 29 people were rescued from the rubble.[17]

Investigation

The Kansas City Star hired architectural engineer Wayne G. Lischka[18] to investigate the collapse, and he discovered a significant change to the original design of the walkways. The Star and its associated publication the Kansas City Times won a Pulitzer Prize in 1982 for their coverage of the collapse.[19]

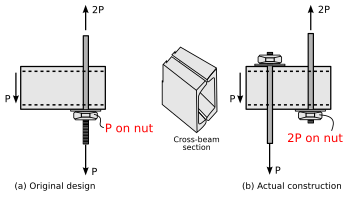

The two walkways were suspended from a set of 1.25-inch-diameter (32 mm) steel tie rods,[20] with the second-floor walkway hanging directly under the fourth-floor walkway. The fourth-floor walkway platform was supported on three cross-beams suspended by steel rods retained by nuts. The cross-beams were box girders made from C-channel strips welded together lengthwise, with a hollow space between them. The original design by Jack D. Gillum and Associates specified three pairs of rods running from the second-floor walkway to the ceiling, passing through the beams of the fourth-floor walkway, with a bolt at the middle of each tie rod tightened up to the bottom of the fourth-floor walkway, and a bolt at the bottom of each tie rod tightened up to the bottom of the second-floor walkway. Even this original design supported only 60% of the minimum load required by Kansas City building codes.[21]

Havens Steel Company manufactured the rods, and they objected that the whole rod below the fourth floor would have to be threaded in order to screw on the nuts to hold the fourth-floor walkway in place. These threads would be subject to damage as the fourth-floor structure was hoisted into place. Havens, therefore, proposed that two separate and offset sets of rods be used: the first set suspending the fourth-floor walkway from the ceiling, and the second set suspending the second-floor walkway from the fourth-floor walkway.[22]

In the original design, the beams of the fourth-floor walkway had to support only the weight of the fourth-floor walkway, with the weight of the second-floor walkway supported completely by the rods. In the revised design, however, the fourth-floor beams supported both the fourth and second-floor walkways, despite being only strong enough for 30% of that load.[21]

The serious flaws of the revised design were compounded by the fact that both designs placed the bolts directly through a welded joint connecting two C-channels, the weakest structural point in the box beams. The original design was for the welds to be on the sides of the box beams, rather than on the top and bottom. Photographs of the wreckage show excessive deformations of the cross-section.[23] During the failure, the box beams split along the weld and the nut supporting them slipped through the resulting gap, which was consistent with reports that the upper walkway at first fell several inches, after which the nut was held only by the upper side of the box beams; then the upper side of the box beams failed as well, allowing the entire walkway to fall.[citation needed]

Investigators concluded that the underlying problem was a lack of proper communication between Jack D. Gillum and Associates and Havens Steel. In particular, the drawings prepared by Gillum and Associates were only preliminary sketches, but Havens interpreted them as finalized drawings. Gillum and Associates failed to review the initial design thoroughly and accepted Havens' proposed plan without performing necessary calculations or viewing sketches that would have revealed its serious intrinsic flaws — in particular, doubling the load on the fourth-floor beams.[21] A Gillum and Associates project engineer, who accepted Havens' proposed plan over the phone, was stripped of his professional license.[24]

Aftermath

The Missouri Board of Architects, Professional Engineers, and Land Surveyors found the engineers at Jack D. Gillum and Associates who had approved the final drawings to be culpable of gross negligence, misconduct, and unprofessional conduct in the practice of engineering. They were acquitted of all the crimes with which they were initially charged, but the company lost its engineering licenses in the states of Missouri, Kansas, and Texas, as well as its membership with the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).[23][21][24]

At least $140 million (equivalent to $397.3 million in 2023)[25] was awarded to victims and their families in subsequent civil lawsuits; a large amount of this money was from Crown Center Corporation, a subsidiary of Hallmark Cards which was the owner of the hotel real estate; Hyatt operated the hotel for a fee as a management company and did not own the building.[26][27]

The Hyatt collapse remains a classic model for the study of engineering ethics and errors, as well as disaster management.[28] Jack D. Gillum (1928–2012)[29] was an engineer of record for the Hyatt project, and he occasionally shared his experiences at engineering conferences in the hope of preventing future mistakes.[24]

Several rescuers suffered considerable stress due to their experience and later relied upon each other in an informal support group.[10] Jackhammer operator "Country" Bill Allman died by suicide.[30] The hotel was renamed the Hyatt Regency Crown Center in 1987, and again the Sheraton Kansas City at Crown Center in 2011. It has been renovated numerous times since, though the lobby retains the same layout and design. A memorial was dedicated by Skywalk Memorial Foundation, a non-profit organization established for victims of the Hyatt collapse, on November 12, 2015 in Hospital Hill Park across the street from the hotel.[31][32]

See also

References

- ^ Marshall, Richard D.; et al. (May 1982). Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency walkways collapse. Building Science Series. Vol. 143. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Martin, David (September 14, 2011). "Former Chiefs doctor Joseph Waeckerle--a veteran of the NFL's concussion wars--is on a mission to protect young players". The Pitch. Kansas City. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Petroski, Henry (1992). To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Structural Design. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-73416-1.

- ^ Staff (July 18, 1981). "45 Killed at Hotel in Kansas City, Mo., as Walkways Fall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 17, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b National Bureau of Standards (May 1982). "Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse". US Department of Commerce. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ "Hotel Horror". Kansas City Public Library. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Ramroth, William (2007). Planning for disaster: how natural and man-made disasters shape the built environment. Kaplan Business. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-4195-9373-4.

- ^ a b c Friedman, Mark (2002). Everyday crisis management: how to think like an emergency physician. First Decision Press. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-0-9718452-0-6. Retrieved June 14, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b D'Aulairey, Emily; Per Ola D'Aulairey (July 1982). "There Wasn't Time To Scream". The Reader's Digest: 49–56.

- ^ a b Associated Press (July 15, 2001). "Lives forever changed by skywalk collapse". Lawrence Journal-World. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b McGuire, Donna. "20 years later: Fatal disaster remains impossible to forget". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Associated Press Library of Disasters: Nuclear and Industrial Disasters. Grolier Academic Reference. 1997. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7172-9176-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Waeckerle, Joseph F. (March 21, 1991). "Disaster Planning and Response". New England Journal of Medicine. 324 (324): 815–821. doi:10.1056/nejm199103213241206.

- ^ O'Reilly, Kevin (January 2, 2012). "Disaster medicine dilemmas examined". American Medical News. 55 (1). Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Staff writers. "Disaster made heroes of the helpers". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hyatt skywalks collapse changed lives forever," Kansas City Star, Kevin Murphy, July 9, 2011.

- ^ Incident Command System for Structural Collapse Incidents; ICSSCI-Student Manual (FEMA P-702 ed.). FEMA. 2006. pp. SM 1–7. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ "History & Education". Archived from the original on February 7, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Pulitzer Prizes – Local General or Spot News Reporting". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Baura, Gail (2006). Engineering ethics: an industrial perspective. Academic Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-12-088531-2.

- ^ a b c d "Hyatt Regency Walkway Collapse". School of Engineering, University of Alabama. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Whitbeck, Caroline (1998). Ethics in Engineering Practice and Research. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-521-47944-4.

- ^ a b "Hyatt Regency Walkway Collapse". Engineering.com. October 24, 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2006.

- ^ a b c Montgomery, Rick (July 15, 2001). "20 years later: Many are continuing to learn from skywalk collapse". Kansas City Star. p. A1. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ "Hyatt Regency Disaster | ThinkReliability, Case Studies". ThinkReliability.

- ^ Staff writers (July 18, 2001). "The Hyatt Regency disaster 20 years later". Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Auf der Heide, Erik (1989). Disaster Response: Principles of Preparation and Coordination. St. Louis MO: C.V. Mosby Company. pp. 3, 72, 76, 82. ISBN 0-8016-0385-4.

- ^ "Obituary: Jack D. Gillum". Horan & McConaty Funeral Home. July 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Murphy, Kevin; Rick Alm and Carol Powers (2011). The last dance : the skywalks disaster and a city changed : in memory, 30 years later (1st ed.). Kansas City, Mo. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-61169-012-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Campbell, Matt (November 12, 2015). "Memorial to Kansas City skywalk disaster finally a reality". Kansas City Star. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ "Skywalk Memorial Plaza Dedicated". Kansas City Parks & Recreation. November 13, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

Further reading

- Petroski, Henry (1985). "Accidents Waiting To Happen". To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Structural Design. New York: Random House. pp. 85–93.

After the walkways were up there were reports that construction workers found the elevated shortcuts over the atrium unsteady under heavy wheelbarrows, but the construction traffic was simply rerouted and the designs were apparently still not checked or found wanting.

- Marshall, Richard D.; et al. (May 1982). Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency walkways collapse. Building Science Series. Vol. 143. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- Levey, M.; Salvadori, M.; Woest, K. (1994). Why Buildings Fall Down: How Structures Fail. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31152-5.

- Murphy, Kevin; Rick Alm and Carol Powers. The Last Dance : The Skywalks Disaster and a City Changed : In Memory, 30 Years Later (1st ed.). Kansas City, Mo. ISBN 978-1-61169-012-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) – (All author royalties of this book are being donated to the memorial project)

External links

- Engineering Ethics – includes photos of the failed walkway components[dead link]

- Failure By Design – physics presentation

- Network news feature from July 23, 1981, including interviews