History of baseball in the United States: Difference between revisions

{{mergefrom|Major League Baseball Lore}} |

LaffyTaffer (talk | contribs) m Reverted 1 edit by 12.77.11.238 (talk) to last revision by Mudwater |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|none}} |

|||

{{mergefrom|Major League Baseball Lore}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|date=November 2016|talk=Sections needing citations}} |

|||

{{POV}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2022}} |

|||

''Part of the [[History of baseball]] series.'' |

|||

[[File:First known photograph of a baseball game in progress.jpg|thumb|275px|The earliest known photograph of a baseball game in progress, 1869]] |

|||

{{HistBaseball nav|country}} |

|||

The '''history of baseball in the United States''' dates to the 19th century, when boys and amateur enthusiasts played a [[baseball]]-like game by their own informal rules using homemade equipment. The popularity of the sport grew and amateur men's ball clubs were formed in the 1830–50s. [[Semi-professional]] baseball clubs followed in the 1860s, and the first professional leagues arrived in the post-[[American Civil War]] 1870s. |

|||

==Early history== |

|||

[[Image:Conner-prairie-baseball.jpg|300px|thumb|1886 baseball demonstration at [[Conner Prairie]] living history museum.]] |

|||

== Early history == |

|||

The earliest known mention of [[baseball]] in the United States was in a [[1791]] [[Pittsfield, Massachusetts]] bylaw banning the playing of the game within 80 yards of the town meeting house. |

|||

The earliest known mention of baseball in the [[United States|US]] is either a 1786 diary entry by a [[Princeton University]] student who describes playing "baste ball,"<ref>"A fine day, play baste ball in the campus but am beaten for I miss both catching and striking the ball." https://protoball.org/1786.1</ref> or a 1791 [[Pittsfield, Massachusetts]], ordinance that barred the playing of baseball within {{convert|80|yd|m}} of the town meeting house and its glass windows.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=1799618|website=ESPN|title=Pittsfield uncovers earliest written reference to game|date=May 11, 2004}}</ref> Another early reference reports that ''base ball'' was regularly played on Saturdays in 1823 on the outskirts of [[New York City]] in an area that today is [[Greenwich Village]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://static.espn.go.com/mlb/news/2001/0708/1223744.html|author=ESPN.com|title=Articles show 'base ball' was played in 1823|date=July 8, 2001|access-date=July 28, 2006}}</ref> The Olympic Base Ball Club of Philadelphia was organized in 1833.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The History Of Baseball timeline. |url=https://www.timetoast.com/timelines/the-history-of-baseball--3 |access-date=2022-11-10 |website=Timetoast timelines |date=January 18, 1833 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:1844-magnolia.jpg|thumb|250px|Invitation to the "1st Annual Ball of the Magnolia Ball Club" of New York, c. 1843, depicting the Colonnade Hotel at the Elysian Fields and a group of men playing baseball: the earliest known image of grown men playing the game.]] |

|||

In 1903, the British-born sportswriter [[Henry Chadwick (writer)|Henry Chadwick]] published an article speculating that baseball was derived from an English game called [[rounders]], which Chadwick had played as a boy in England. Baseball executive [[A. G. Spalding|Albert Spalding]] disagreed, asserting that the game was fundamentally American and had hatched on American soil. To settle the matter, the two men appointed a commission, headed by [[Abraham G. Mills|Abraham Mills]], the fourth president of the [[National League (baseball)|National League of Professional Baseball Clubs]]. The commission, which also included six other sports executives, labored for three years, finally declaring that [[Abner Doubleday]] had invented the national pastime. Doubleday "...never knew that he had invented baseball. But 15 years after his death, he was anointed as the father of the game," writes baseball historian John Thorn. The [[Doubleday myth|myth about Doubleday inventing the game of baseball]] actually came from a [[Colorado]] mining engineer who claimed to have been present at the moment of creation. The miner's tale was never corroborated, nonetheless the myth was born and persists to this day.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.npr.org/2011/03/16/134570236/the-secret-history-of-baseballs-earliest-days |title=The 'Secret History' Of Baseball's Earliest Days |work=NPR |date=March 16, 2011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news | title=A '215th birthday' for Pittsfield as baseball's 'Garden of Eden' | last=Ryan | first=Andrew | newspaper=The Boston Globe | url=http://www.boston.com/news/globe/city_region/breaking_news/2006/09/a_215th_birthda.html | date=September 5, 2006 | access-date=September 30, 2009 | quote=In 2004, baseball historian John Thorn discovered the 1791 town ordinance, putting Pittsfield's connection to baseball 48 years before Abner Doubleday accepted invention of the game in 1839 in Cooperstown, N.Y., where the National Baseball Hall of Fame now stands. The Hall of Fame recognized the ordinance as the first known reference to the game and honored the town with a plaque.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pittsfield-ma.org/subpage.asp?ID=226 |title=Pittsfield is "Baseball's Garden of Eden" |date=May 11, 2004 |access-date=September 20, 2009 |quote=…for the Preservation of the Windows in the New Meeting House … no Person or Inhabitant of said town, shall be permitted to play at any game called Wicket, Cricket, Baseball, Football, Cat, Fives or any other game or games with balls, within the Distance of Eighty Yards from said Meeting House. |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090721171602/http://www.pittsfield-ma.org/subpage.asp?ID=226 |archive-date=21 July 2009 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title=Original by-law | url=http://www.pittsfield-ma.org/images/downloads/Baseball_By-Law.pdf | date=September 5, 1791 | access-date=September 30, 2009 | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110726002030/http://www.pittsfield-ma.org/images/downloads/Baseball_By-Law.pdf | archive-date=July 26, 2011 }}</ref> Which does not mean that the Doubleday myth does not continue to be disputed; in fact, it is likely that the parentage of the modern game of baseball will be in some dispute until long after such future time when the game is no longer played.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Thorn |first1=John |title=Debate Over Baseball's Origins Spills Into Another Century |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/13/sports/baseball/13thorn.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/13/sports/baseball/13thorn.html |archive-date=2022-01-01 |url-access=limited |work=The New York Times |date=12 March 2011 }}{{cbignore}}</ref> |

|||

The first team to play baseball under modern rules is believed to be the [[Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York|New York Knickerbockers]]. The club was founded on September 23, 1845, as a breakaway from the earlier Gotham Club.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Griffin |first=John |date=2022-01-25 |title=The Knickerbocker Rules: the first organized rulebook for what would become baseball |url=https://www.pinstripealley.com/2022/1/25/22899998/mlb-history-knickerbocker-club-rules-new-york-town-ball-rounders-alexander-cartwright |access-date=2022-11-10 |website=Pinstripe Alley |language=en}}</ref> The new club's by-laws committee, [[William R. Wheaton]] and [[William H. Tucker (baseball)|William H. Tucker]], formulated the ''[[Knickerbocker Rules]]'', which, in large part, dealt with organizational matters but which also laid out some new rules of play.<ref name=totalb>{{Cite book| publisher = Sport Media Pub.| isbn = 189496327X| last = Thorn| first = John| title = Total baseball: the ultimate baseball encyclopedia| location = Wilmington, Delaware| date = 2004}}{{page needed|date=June 2020}}</ref> One of these prohibited ''soaking'' or ''plugging'' the runner; under older rules, a fielder could put a runner out by hitting the runner with the thrown ball, as in the common schoolyard game of [[kickball]]. The Knickerbocker Rules required fielders to tag or force the runner. The new rules also introduced base paths, foul lines and foul balls; in "town ball" every batted ball was fair, as in [[cricket]], and the lack of runner's lanes led to wild chases around the infield. |

|||

Another early reference reports that "base ball" was regularly played on Saturdays on the outskirts of [[New York City]] (in what is now [[Greenwich Village]]) in 1823.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://espn.go.com/mlb/news/2001/0708/1223744.html|author=ESPN.com|title=Articles show 'base ball' was played in 1823|date=[[2001-07-08]]|accessdate=2006-07-28}}</ref> |

|||

Initially, Wheaton and Tucker's innovations did not serve the Knickerbockers well. In the first known competitive game between two clubs under the new rules, played at [[Elysian Fields, Hoboken, New Jersey|Elysian Fields]] in [[Hoboken, New Jersey]], on June 19, 1846, the "New York nine" (almost certainly the Gotham Club) humbled the Knickerbockers by a score of 23 to 1. Nevertheless, the Knickerbocker Rules were rapidly adopted by teams in the New York area and their version of baseball became known as the "New York Game" (as opposed to the less rule-bound "Massachusetts Game," played by clubs in New England, and "Philadelphia Town-ball"). |

|||

The first team to play baseball under modern rules were the [[New York Knickerbockers]]. The club was founded on [[September 23]], [[1845]], as a social club for the upper middle classes of [[New York City]], and was strictly [[amateur]] until its disbandment. The club members, led by [[Alexander Cartwright]], formulated the "Knickerbocker Rules", which in large part deal with organizational matters but which also lay out rules for playing the game. One of the significant rules was the prohibition of "soaking" or "plugging" the runner; under older rules, a fielder could put a runner out by hitting the runner with the thrown ball. The Knickerbocker Rules required fielders to tag or force the runner, as is done today, and avoided a lot of the arguments and fistfights that resulted from the earlier practice. |

|||

In spite of its rapid growth in popularity, baseball had yet to overtake the British import, [[cricket]]. As late as 1855, the New York press was still devoting more space to coverage of cricket than to baseball.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

Writing the rules didn't help the Knickerbockers in the first known competitive game between two clubs under the new rules, played at Elysian Fields in [[Hoboken, New Jersey]] on [[June 19]], [[1846]]. The self-styled "New York Nine" humbled the Knickerbockers by a score of 23 to 1. Nevertheless, the Knickerbocker Rules were rapidly adopted by teams in the New York area and their version of baseball became known as the "New York Game" (as opposed to the "Massachusetts Game", played by clubs in the Boston area). |

|||

|page=56 |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OTZexfpmyDwC |

|||

|title=Offside: soccer and American exceptionalism |

|||

|first=Andrei S. |

|||

|last=Markovits |

|||

|author2=Steven L. Hellerman |

|||

|publisher=Princeton University Press |

|||

|year=2001 |

|||

|isbn=0-691-07447-X |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

At a 1857 convention of sixteen New York area clubs, including the Knickerbockers, the [[National Association of Base Ball Players]] (NABBP) was formed. It was the first official organization to govern the sport and the first to establish a championship. The convention also formalized three key features of the game: 90 feet distance between the bases, 9-man teams, and 9-inning games (under the Knickerbocker Rules, games were played to 21 runs). During the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], soldiers from different parts of the United States played baseball together, leading to a more unified national version of the sport. Membership in the NABBP grew to almost 100 clubs by 1865 and to over 400 by 1867, including clubs from as far away as [[California]]. Beginning in 1869, the league permitted [[professional]] play, addressing a growing practice that had not been previously permitted under its rules. The first and most prominent professional club of the NABBP era was the [[Cincinnati Red Stockings]] in Ohio, which went undefeated in 1869 and half of 1870. After the Cincy club broke up at the end of that season, four key members including player/manager [[Harry Wright]] moved to Boston under owner and businessman [[Ivers Whitney Adams]] and became the "Boston Red Stockings" and the [[Boston Base Ball Club]]. |

|||

[[File:Take Me Out to the Ballgame (ISRC USUAN1100313).mp3|thumb|[[Take Me Out to the Ball Game|Take Me Out to The Ballgame]]]] |

|||

In 1858, at the Fashion Race Course in the [[Corona, Queens|Corona]] neighborhood of [[Queens]] (now part of [[New York City]]), the first games of baseball to charge admission were played.<ref>This at least has long been believed to be the case. There is however evidence of an earlier game with paid admission taking place in Massachusetts in 1858 between the Winthrop club of Holliston and Olympic of Boston: "About an acre of ground was surrounded by a strong rope, and policemen were stationed at regular intervals to keep back the crowd, while a few were admitted within the enclosure by tickets, and occupied a position on the western side." ''Boston Traveler'', June 1, 1858. This game, however, was likely played according to New England rules.</ref> The All Stars of [[Brooklyn]], including players from the [[Brooklyn Atlantics|Atlantic]], [[Excelsior of Brooklyn|Excelsior]], Putnam and [[Eckford of Brooklyn|Eckford]] clubs, took on the All Stars of New York ([[Manhattan]]), including players from the [[Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York|Knickerbocker]], Gotham, Eagle and Empire clubs. These are commonly believed to the first all-star baseball games.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Ceresi |first1=Frank |last2=McMains |first2=Carol |title=The 1858 Fashion Race Course Base Ball Match |url=https://www.baseball-almanac.com/treasure/autont2006b.shtml |website=Baseball Almanac |year=2006 }}</ref><ref>All Star Games of 1858 {{cite web|url=http://baseballhistoryblog.com/2725/all-star-games-of-1858 |title=All-Star Games of 1858 | Baseball History Blog |access-date=2013-08-05 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131016014635/http://baseballhistoryblog.com/2725/all-star-games-of-1858/ |archive-date=2013-10-16 }} Accessed August 5, 2013</ref> |

|||

==Growth== |

|||

==Professionalism and the rise of the major leagues== |

|||

Before the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], baseball competed for public interest with [[cricket]] and regional variants of baseball, notably [[town ball]] played in [[Philadelphia]] and the [[Massachusetts Game]] played in [[New England]]. In the 1860s, aided by the Civil War, [[Knickerbocker Rules|"New York" style]] baseball expanded into a national game. Baseball began to overtake cricket in popularity, impelled by its much shorter duration relative to the form of cricket [[First-class cricket|played at the time]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Crown |first=Daniel |date=2017-10-19 |title=The Battle Between Baseball and Cricket for American Sporting Supremacy |url=http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/cricket-baseball-american-sport |access-date=2023-01-05 |website=Atlas Obscura |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |title=Why cricket and America are made for each other |url=https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2022/12/20/why-cricket-and-america-are-made-for-each-other |access-date=2023-01-05 |newspaper=The Economist |issn=0013-0613}}</ref> As its first governing body, the [[National Association of Base Ball Players]] was formed. The NABBP soon expanded into a truly national organization, although most of the strongest clubs remained those based in the country's northeastern part. In its 12-year history as an amateur league, the [[Brooklyn Atlantics|Atlantic Club of Brooklyn]] won seven championships, establishing themselves as the first true dynasty in the sport. However, [[New York Mutuals|Mutual of New York]] was widely considered one of the best teams of the era. By the end of [[1865 in baseball|1865]], almost 100 clubs were members of the NABBP. By 1867, it ballooned to over 400 members, including some clubs from as far away as California. One of these western clubs, Chicago (dubbed the "White Stockings" by the press for their uniform hosiery), won the championship in 1870.<ref>Today, they are known as the [[Chicago Cubs]], the oldest professional sports team in North America if not the world. A second NAPBB club is also still in existence, the aforementioned "Red Stockings" of Boston, now known as the [[Atlanta Braves]].</ref> Because of this growth, regional and state organizations began to assume a more prominent role in the governance of the amateur sport at the expense of the NABBP. At the same time, the professionals soon sought a new governing body. |

|||

[[File:William E. Robertson, President of Buffalo Federal League baseball team LCCN2014695917 (cropped).jpg|thumb|150px|[[William E. Robertson]]]] |

|||

==Professionalism== |

|||

In 1870, a schism formed between professional and amateur ballplayers. The NABBP split into two groups. The [[National Association of Professional Baseball Players|National Association of ''Professional'' Base Ball Players]] operated from [[1871]] through [[1875]], and is considered by some to have been the first major league. Its amateur counterpart disappeared after only a few years. |

|||

The NABBP of America was initially established upon principles of [[amateurism]]. However, even early in the Association's history, some star players such as [[Jim Creighton|James Creighton]] of [[Excelsior of Brooklyn|Excelsior]] received compensation covertly or indirectly. In [[1866 in sports|1866]], the NABBP investigated [[Athletic of Philadelphia]] for paying three players including [[Lip Pike]], but ultimately took no action against either the club or the players. In many cases players, quite openly, received a cut of the gate receipts.<ref>''New York Daily News,'' April 21, 1867. https://protoball.org/1867.13</ref> Clubs playing challenge series were even accused of agreeing beforehand to split the earlier games to guarantee a decisive (and thus more certain to draw a crowd) "rubber match".<ref>Thorn, John, ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden'', 211</ref> To address this growing practice, and to restore integrity to the game, at its December [[1868 in sports|1868]] meeting the NABBP established a professional category for the [[1869 in sports|1869]] season. Clubs desiring to pay players were now free to declare themselves [[professional]]. |

|||

The [[Cincinnati Red Stockings]] were the first to declare themselves openly professional, and were aggressive in recruiting the best available players. Twelve clubs, including most of the strongest clubs in the NABBP, ultimately declared themselves professional for the [[1869 in sports|1869]] season. |

|||

The professional [[National League]] of Professional Base Ball Clubs, which is still existent, was established in 1875 after the National Association proved ineffective. The emphasis was now on "clubs" rather than "players". Clubs now had the ability to enforce player contracts, preventing players from jumping to higher-paying clubs. Clubs in turn were required to play their full schedule of games, rather than forfeiting games scheduled once out of the running for the league championship, as happened frequently under the National Association. A concerted effort was made to reduce the amount of gambling on games which was leaving the validity of results in doubt. |

|||

The first attempt at forming a [[Major North American professional sports teams|major league]] produced the [[National Association of Professional Base Ball Players]], which lasted from 1871 to 1875. The now all-professional Chicago "White Stockings" (today the [[Chicago Cubs]]), financed by businessman [[William Hulbert]], became a charter member of the league along with a new Red Stockings club (now the [[Atlanta Braves]]), formed in Boston with four former Cincinnati players. The Chicagos were close contenders all season, despite the fact that the [[Great Chicago Fire]] had destroyed the team's home field and most of their equipment. Chicago finished the season in second place, but were ultimately forced to drop out of the league during the city's recovery period, finally returning to National Association play in 1874. Over the next couple of seasons, the [[Ivers Whitney Adams#Baseball|Boston club]] dominated the league and hoarded many of the game's best players, even those who were under contract with other teams. After [[Davy Force]] signed with Chicago, and then breached his contract to play in Boston, Hulbert became discouraged by the "contract jumping" as well as the overall disorganization of the N.A. (for example, weaker teams with losing records or inadequate gate receipts would simply decline to play out the season), and thus spearheaded the movement to form a stronger organization. The result of his efforts was the formation of a much more "ethical" league, which was named the [[National League (baseball)|National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs]] (NL). After a series of rival leagues were organized but failed (most notably the [[American Association (19th century)|American Base Ball Association]] (1882–1891), which spawned the clubs which would ultimately become the [[Cincinnati Reds]], [[Pittsburgh Pirates]], [[St. Louis Cardinals]] and [[Brooklyn Dodgers]]), the current [[American League]] (AL), evolving from the minor Western League of 1893, was established in 1901. |

|||

At the same time, a "[[gentlemen's agreement]]" was struck between the clubs which endeavored to [[Baseball color line|bar non-white players]] from professional baseball, a bar which was in existence until [[1947]]. It is a common misconception that [[Jackie Robinson]] was the first African-American major-league ballplayer; he was actually only the first after a long gap. [[Moses Fleetwood Walker]] and his brother Welday Walker were unceremoniously dropped from major and minor-league rosters in the 1880s, as were other African-Americans in baseball. An unknown number of African-Americans played in the major leagues as Indians, or South or Central Americans. And a still larger number played in the minor leagues and on amateur teams as well. In the majors, however, it was not until Robinson (in the National League) and [[Larry Doby]] (in the American League) emergence that baseball would begin to remove its color bar. |

|||

==Rise of the major leagues== |

|||

The early years of the National League were nonetheless tumultuous, with threats from rival leagues and a rebellion by players against the hated "reserve clause", which restricted the free movement of players between clubs. Competitive leagues formed regularly, and also disbanded regularly. The most successful was the American Association ([[1881]]–[[1891]]), sometimes called the "beer and whiskey league" for its tolerance of the sale of alcoholic beverages to spectators. For several years, the National League and American Association champions met in a postseason championship series—the first attempt at a [[Baseball/World Series|World Series]]. |

|||

[[Image:Pre-1900 MLB teams.png|thumb|480px|Cities that hosted 19th century MLB teams, with cities that still host their 19th century team in black. With the exception of a team in Washington and a few short-lived teams in Virginia and Kentucky, major league baseball would not expand out of the [[Northeastern United States|Northeast]] and the [[Midwestern United States|Midwest]] until after World War II.]] |

|||

In 1870, a [[wikt:schism|schism]] developed between professional and amateur ballplayers. The NABBP split into two groups. The [[National Association of Professional Base Ball Players]] operated from 1871 through 1875 and is considered by some to have been the first major league. Its amateur counterpart disappeared after only a few years. |

|||

William Hulbert's National League, which was formed after the National Association proved ineffective, put its emphasis on "clubs" rather than "players". Clubs now had the ability to enforce player contracts and prevent players from jumping to higher-paying clubs. Clubs in turn were required to play their full schedule of games, rather than forfeiting scheduled games once out of the running for the league championship, a practice that had been common under the National Association. A concerted effort was also made to reduce the amount of gambling on games which was leaving the validity of results in doubt.<ref>John Thorn writes that while gambling had played a significant role in drawing adult fans to what was once considered a kid's game, it also came to tempt less-than-honest on-field performances from some underpaid players. The "throwing" of games had become prevalent—and obvious—enough to cause considerable concern to team owners who depended on ticket sales for their profits.</ref> |

|||

The [[Union Association]] survived for only one season ([[1884]]), as did the [[Players League]] ([[1890]]), a fascinating attempt to return to the [[National Association]] structure of a league controlled by the players themselves. Both leagues, however, are considered major leagues by many baseball researchers because of the perceived high caliber of play (for a brief time anyway) and the number of star players featured. Some researchers have disputed the major league status of both leagues, claiming that the vast majority of their players were far below the National League's level of play at the time. |

|||

Around this time, a [[gentlemen's agreement]] was struck between the clubs to [[Baseball color line|exclude non-white players]] from professional baseball, a ''de facto'' ban that remained in effect until 1947. It is a common misconception that [[Jackie Robinson]] was the first African-American major-league ballplayer; he was actually only the first after a long gap (and the first in the modern era). [[Moses Fleetwood Walker]] and his brother [[Weldy Walker]] were unceremoniously dropped from major and minor-league rosters in the 1880s, as were other African-Americans in baseball. An unknown number of African-Americans played in the major leagues by representing themselves as Indians, or South or Central Americans, and a still larger number played in the minor leagues and on amateur teams. In the majors, however, it was not until the signing of Robinson (in the National League) and [[Larry Doby]] (in the American League) that baseball began to relax its ban on African-Americans. |

|||

There were dozens of leagues, large and small, at this time. So what made the National League major? Control of the major cities, particularly New York City, the edgy, emotional nerve center of baseball with several clubs. They had both the biggest national media distribution systems of the day, and the populations that could generate big enough revenues for teams to hire the best players in the country. |

|||

[[File:OSIA baseball team.jpg|thumb|412x412px|[[Order Sons of Italy in America|OSIA]] team]] |

|||

Many leagues, including the venerable Eastern League, survived in parallel with the National League. One, the Western League, founded in 1893, became aggressive. Its fiery leader [[Ban Johnson]], railed against the National League, and promised that he would build a new league that would grab the best players, and field the best teams. It began play in April 1894. |

|||

The early years of the National League were tumultuous, with threats from rival leagues and a rebellion by players against the hated "[[reserve clause]]", which restricted the free movement of players between clubs. Competitive leagues formed regularly, and disbanded just as regularly. The most successful of these was the [[American Association (19th century)|American Association]] of 1882–1891, sometimes called the "beer and whiskey league" for its tolerance of the sale of alcoholic beverages to spectators. For several years, the National League and American Association champions met in a postseason [[List of pre-World Series baseball champions#Champions from 1876 to 1904|World's Championship Series]]—the first attempt at a [[World Series]]. |

|||

The [[Union Association]] survived for only one season (1884), as did the [[Players' League]] (1890), which was an attempt to return to the [[National Association of Professional Base Ball Players|National Association]] structure of a league controlled by the players themselves. Both leagues are considered major leagues by many baseball researchers because of the perceived high caliber of play and the number of star players featured. However, some researchers have disputed the major league status of the Union Association, pointing out that franchises came and went and contending that the St. Louis club, which was deliberately "stacked" by the league's president (who owned that club), was the only club that was anywhere close to major-league caliber. |

|||

The teams were [[Detroit Tigers|Detroit]] (the only league team that has not moved since), [[Cleveland Indians|Grand Rapids]], [[Oakland Athletics|Indianapolis]], [[Minnesota Twins|Kansas City]], [[Baltimore Orioles|Milwaukee]], [[Minneapolis Millers|Minneapolis]], [[Chicago White Sox|Sioux City]] and [[Boston Red Sox|Toledo]]. Prior to the 1900 season, the league changed its name to the [[American League]], moved several franchises to larger, strategic locations, and in 1901 declared its intent to operate as a major league. |

|||

[[File:Baseball Players Practicing Thomas Eakins 1875.jpeg|left|thumb|300px|Baseball Players Practicing, by [[Thomas Eakins]] (1875)]] |

|||

In fact, there were dozens of leagues, large and small, in the late 19th century. What made the National League "major" was its dominant position in the major cities, particularly the edgy, emotional nerve center of baseball that was New York City. Large, concentrated populations offered baseball teams national media distribution systems and fan bases that could generate sufficient revenues to afford the best players in the country. |

|||

A number of the other leagues, including the venerable Eastern League, threatened the dominance of the National League. The Western League, founded in 1893, became particularly aggressive. Its fiery leader [[Ban Johnson]] railed against the National League and promised to grab the best players and field the best teams. The Western League began play in April 1894 with teams in Detroit (now the American League [[Detroit Tigers]], the only league team that has not moved since), [[Cleveland Indians|Grand Rapids]], [[Oakland Athletics|Indianapolis]], [[Minnesota Twins|Kansas City]], [[Baltimore Orioles|Milwaukee]], [[Minneapolis Millers|Minneapolis]], [[Chicago White Sox|Sioux City]] and [[Boston Red Sox|Toledo]]. Prior to the 1900 season, the league changed its name to the [[American League]] and moved several franchises to larger, strategic locations. In 1901 the American League declared its intent to operate as a major league. |

|||

The resulting bidding war for players led to widespread contract-breaking and legal hassles. One of the most famous involved star second baseman [[Napoleon Lajoie]], who went across town in Philadelphia from the National League Phillies to the American League Athletics in 1901. Barred by a court injunction from playing baseball in the state of Pennsylvania the next year, Lajoie saw his contract traded to the Cleveland team; he would play for and manage Cleveland for many years. |

|||

The resulting bidding war for players led to widespread contract-breaking and legal disputes. One of the most famous involved star second baseman [[Napoleon Lajoie]], who in 1901 went across town in Philadelphia from the National League Phillies to the American League Athletics. Barred by a court injunction from playing baseball in the state of Pennsylvania the next year, Lajoie was traded to the Cleveland team, where he played and managed for many years. |

|||

The war between the American and National also caused shock waves throughout the rest of the baseball world. The result was a meeting at the Leland Hotel in Chicago in 1901 of every other baseball league. On September 5, 1901 [[Patrick T. Powers]], president of the [[Eastern League]] formed the second [[Minor League Baseball|National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues]], the NABPL or "NA" for short. The design of the association was to maintain the other leagues' independence. |

|||

The war between the American and National leagues caused shock waves across the baseball world. At a meeting in 1901, the other baseball leagues negotiated a plan to maintain their independence. On September 5, 1901, [[Eastern League (1938–2020)|Eastern League]] president [[Patrick T. Powers]] announced the formation of the second [[Minor League Baseball|National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues]], the NABPL (NA). |

|||

To call these leagues "minor" in these days would have been a poorly received mistake. The term 'minor' league did not come into vogue until the Great Depression and St. Louis Cardinals GM [[Branch Rickey]]'s coordinated developmental program, the farm system, came into being in the 1930s. Still, these leagues needed money, and selling players to the more affluent National and American leagues sent them down the road that would strip the "in" from their independent status. |

|||

These leagues did not consider themselves "minor"—a term that did not come into vogue until St. Louis Cardinals general manager [[Branch Rickey]] pioneered the farm system in the 1930s. Nevertheless, these financially troubled leagues, by beginning the practice of selling players to the more affluent National and American leagues, embarked on a path that eventually led to the loss of their independent status. |

|||

For Ban Johnson had other designs for the NA. While the NA continues to this day, he saw it as a tool to end threats from smaller rivals who might some day want to expand in other territories and threaten his league's dominance. |

|||

[[Image:John E Sheridan Pennsylvania Georgetown Baseball c1901.jpg|thumb|300px|Poster for [[Penn Quakers|University of Pennsylvania]] vs. [[Georgetown University]] baseball game, {{circa|1901}}, by [[John E. Sheridan (illustrator)|John E. Sheridan]].]] |

|||

After 1902 both leagues and the NABPL signed a new National Agreement which achieved three things: |

|||

Ban Johnson had other designs for the NA. While the NA continues to this day, he saw it as a tool to end threats from smaller rivals who might some day want to expand in other territories and threaten his league's dominance. |

|||

*First and foremost, it governed player contracts that set up mechanisms to end the cross-league raids on rosters and reinforced the power of the hated [[reserve clause]] that kept players virtual slaves to their baseball masters. |

|||

After 1902 both leagues and the NABPL signed a new National Agreement which achieved three things: |

|||

*Second, it led to the playing of a "[[Baseball/World Series|World Series]]" in 1903 between the two major league champions. The first World Series was won by Boston of the American League. |

|||

* First and foremost, it governed player contracts that set up mechanisms to end the cross-league raids on rosters and reinforced the power of the hated [[reserve clause]] that kept players virtual slaves to their baseball owner/masters. |

|||

* Second, it led to the playing of a "[[Baseball/World Series|World Series]]" in 1903 between the two major league champions. The first World Series was won by Boston of the American League. |

|||

* Lastly, it established a system of control and dominance for the major leagues over the independents. There would not be another Ban Johnson-like rebellion from the ranks of leagues with smaller cities. Selling off player contracts was rapidly becoming a staple business of the independent leagues. During the rough and tumble years of the American–National struggle, player contracts were violated at the independents as well, as players that a team had developed would sign with the majors without any form of compensation to the indy club. |

|||

The new agreement tied independent contracts to the reserve-clause national league contracts. Baseball players were a commodity, like cars. A player's skill set had a price of $5,000. It set up a rough classification system for independent leagues that regulated the dollar value of contracts, the forerunner of the system refined by Rickey and used today. |

|||

*Lastly, it established a system of control and dominance for the major leagues over the independents. There would not be another Ban Johnson-like rebellion from the ranks of leagues with smaller cities. Selling player contracts was rapidly becoming a staple business of the independent leagues. During the rough and tumble years of the American-National struggle, player contracts were violated at the independents as well: Players that the team had developed would sign deals with the National or American leagues without any form of compensation to the indy club. |

|||

It also gave the NA great power. Many independents walked away from the 1901 meeting. The deal with the NA punished those other indies who had not joined the NA and submitted to the will of the majors. The NA also agreed to the deal so as to prevent more pilfering of players with little or no compensation for the players' development. Several leagues, seeing the writing on the wall, eventually joined the NA, which grew in size over the next several years. |

|||

The new agreement tied independent contracts to the reserve-clause national league contracts. Baseball players were a commodity, like cars. $5,000 bought your arm or your bat, and if you didn't like it, find someplace that would hire you. It set up a rough classification system for independent leagues that regulated the dollar value of contracts, the forerunner of the system refined by Rickey and used today. |

|||

In the very early part of the 20th century, known as the "[[dead-ball era]]", baseball rules and equipment favored the "inside game" and the game was played more violently and aggressively than it is today. This period ended in the 1920s with several changes that gave advantages to hitters. In the largest parks, the outfield fences were brought closer to the infield. In addition, the strict enforcement of new rules governing the construction and regular replacement of the ball<ref>Before 1921, a single ball was used for the entire game unless it was lost in the stands—and even then, team security men were employed to reclaim it from fans. Balls would rapidly become misshapen, soft and filthy. The rule change also outlawed the spitball and other pitchers' methods of "doctoring" the ball</ref> caused it to be easier to hit, and be hit harder. |

|||

It also gave the NA great power. Many independents walked away from the 1901 meeting. The deal with the NA punished those other indies who had not joined the NA and submitted to the will of the 'majors.' The NA also agreed to the deal to prevent more pilfering of players with little or no compensation for the players' development. Several leagues, seeing the writing on the wall, eventually joined the NA, which grew in size over the next several years. |

|||

The first professional black baseball club, the Cuban Giants, was organized in 1885. Subsequent professional black baseball clubs played each other independently, without an official league to organize the sport. [[Rube Foster]], a former ballplayer, founded the [[Negro National League (1920–1931)|Negro National League]] in 1920. A second league, the [[Eastern Colored League]], was established in 1923. These became known as the [[Negro league baseball|Negro leagues]], though these leagues never had any formal overall structure comparable to the Major Leagues. The Negro National League did well until 1930, but folded during the [[Great Depression]]. |

|||

==The dead ball era: 1900 to 1919== |

|||

[[Image:cy_young.jpg|thumb|Cy Young, 1911 baseball card]] |

|||

At this time the games tended to be low scoring, dominated by such legendary pitchers as [[Walter Johnson|Walter "The Big Train" Johnson]], [[Cy Young]], [[Christy Mathewson]], and [[Grover Cleveland Alexander]] to the extent that the period 1900–1919 is commonly called the "dead ball era". The term also accurately describes the condition of the baseball itself. Baseballs cost three dollars apiece, a hefty sum at the time, equaling approximately 65 [[inflation|inflation adjusted]] [[US dollars]] as of 2005; club owners were therefore reluctant to spend much money on new balls if not necessary. It was not unusual for a single baseball to last an entire game. By the end of the game, the ball would be dark with grass, mud, and tobacco juice, and it would be misshapen and lumpy from contact with the bat. Balls were only replaced if they were hit into the crowd and lost, and many clubs employed security guards expressly for the purpose of retrieving balls hit into the stands—a practice unthinkable today. |

|||

From 1942 to 1948, the [[Negro World Series]] was revived. This was the golden era of Negro league baseball, a time when it produced some of its greatest stars. In [[1947 Major League Baseball season|1947]], [[Jackie Robinson]] signed a contract with the [[Brooklyn Dodgers]], breaking the [[Baseball color line|color barrier]] that had prevented talented African-American players from entering the white-only major leagues. Although the transformation was not instantaneous, baseball has since become fully [[racial integration|integrated]]. While the Dodgers' signing of Robinson was a key moment in baseball and civil rights history, it prompted the decline of the Negro leagues. The best black players were now recruited for the Major Leagues, and black fans followed. The last Negro league teams folded in the 1960s. |

|||

As a consequence, home runs were rare, and the "inside game" dominated—singles, [[bunt]]s, [[stolen base]]s, the hit-and-run play, and other tactics dominated the strategies of the time. |

|||

Pitchers dominated the game in the 1960s and early 1970s. In [[1973 Major League Baseball season|1973]], the [[designated hitter]] (DH) rule was adopted by the American League, while in the National League, the DH rule was not adopted until March 2022. The rule had been applied in a variety of ways during the World Series; until the adoption of the DH by the National League, the DH rule applied when Series games were played in an American League stadium, and pitchers would bat during Series games played in National League stadiums. There had been continued disagreement about the future of the DH rule in the World Series until league-wide adoption of the DH rule.<ref name="dh rule world series ">{{Cite web |url=https://www.sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/world-series-2016-dh-rule-rob-manfred-cubs-indians-kyle-schwarber/1q6fq8dlg8z9i1vorxe5gadd08 |title=World Series DH rule is not changing any time soon, MLB's Rob Manfred says |last=Dinotto |first=Marcus |date=2016-10-29 |website=www.sportingnews.com |language=en |access-date=2019-05-11}}</ref> |

|||

Despite this, there were also several superstar hitters, the most famous being [[Honus Wagner]], held to be one of the greatest [[shortstop]]s to ever play the game, and Detroit's [[Ty Cobb]], the "Georgia Peach". Cobb was a mean-spirited man, fiercely competitive and loathed by many of his fellow professionals, but his career [[batting average]] of .366 has yet to be bested. |

|||

During the late 1960s, the [[Major League Baseball Players Association|Baseball Players Union]] became much stronger and conflicts between owners and the players' union led to major work stoppages in 1972, 1981, and 1994. The [[1994–95 Major League Baseball strike|1994 baseball strike]] led to the cancellation of the World Series, and was not settled until the spring of 1995. In the late 1990s, functions that had been administered separately by the two major leagues' administrations were united under the rubric of [[Major League Baseball]] (MLB). |

|||

===The Merkle incident=== |

|||

The [[1908]] pennant races in both the AL and NL were among the most exciting ever witnessed; neither was decided until the final day of play. The conclusion of the National League season, in particular, involved a bizarre chain of events, often referred to as the Merkle Boner. On [[September 23]], [[1908]], the [[San Francisco Giants|New York Giants]] and [[Chicago Cubs]] played a game in the [[Polo Grounds]]. Nineteen-year-old rookie first baseman Fred Merkle, later to become one of the best players at his position in the league, was on first base, with teammate Moose McCormick on third with two out and the game tied. Giants shortstop Al Bridwell socked a single, scoring McCormick and apparently winning the game. However, Merkle, instead of advancing to second base, ran toward the clubhouse to avoid the spectators mobbing the field, which at that time was a common, acceptable practice. Cub second baseman, [[Johnny Evers]], noticed this. In the confusion that followed, Evers claimed to have retrieved the ball and touched second base, forcing Merkle out and nullifying the run scored. The league ordered the game replayed at the end of the season, if necessary. It turned out that the Cubs and Giants ended the season tied for first place, so the game was indeed replayed, and the Cubs won the game, the pennant, and subsequently the [[Baseball/World Series|World Series]] (the last Cub Series victory to date, as it turns out). |

|||

==The dead-ball era: 1901 to 1919== |

|||

For his part, Merkle was doomed to endless criticism and vilification throughout his career for this lapse, which makes his later playing success even more remarkable. In his defense, some baseball historians have suggested that it was not customary for game-ending hits to be fully "run out", and it was only Evers's insistence on following the rules strictly that resulted in this unusual play<ref>{{cite web|url=http://members.aol.com/Jaybird926/merkle.htm|title=Fred Merkle and the 1908 Giants|accessdate=2006-06-19}}</ref>. In fact, earlier in the 1908 season, the identical situation had been brought to the umpires' attention by Evers. While the winning run was allowed to stand on that occasion, the dispute raised the umpires' awareness of the rule, and directly set up the Merkle controversy. |

|||

[[Image:T205 Cy Young.jpg|thumb|Cy Young, 1911 baseball card]] |

|||

[[Image:MLBteams1903to1953.png|thumb|400px|Cities that hosted MLB teams from 1903 to 1953; cities that hosted two teams are in black, cities that hosted one team are in red, and New York/Brooklyn, with three teams, is in orange. Major league baseball did not experience relocation or expansion between 1903 and [[Major League Baseball relocation of 1950s–60s|1953]].]] |

|||

{{Main|Dead-ball era}} |

|||

The period 1901–1919 is commonly called the "Dead-ball era", with low-scoring games dominated by pitchers such as [[Walter Johnson]], [[Cy Young]], [[Christy Mathewson]], and [[Grover Cleveland Alexander]]. The term also accurately describes the condition of the baseball itself. Baseballs cost three dollars each in 1901, a unit price which would be equal to ${{Inflation|US|3|1901}} today. In contrast, modern baseballs purchased in bulk as is the case with professional teams cost about seven dollars each as of 2021 and thus make up a negligible portion of a modern MLB team's operating budget. Due to the much larger relative cost, club owners in the early 20th century were reluctant to spend much money on new balls if not necessary. It was not unusual for a single baseball to last an entire game, nor for a baseball to be reused for the next game especially if it was still in relatively good condition as would likely be the case for a ball introduced late in the game. By the end of the game, the ball would usually be dark with grass, mud, and tobacco juice, and it would be misshapen and lumpy from contact with the bat. Balls were replaced only if they were hit into the crowd and lost, and many clubs employed security guards expressly for the purpose of retrieving balls hit into the stands — a practice unthinkable today. |

|||

===New places to play=== |

|||

At the start of the 20th century baseball attendances were modest by later standards. The average for the 1,110 games in the 1901 season was 3,247.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kenn.com/sports/baseball/mlb/ml_numbers.html|author=Kenn Tomasch|title=Historical attendance figures for Major League Baseball|date=[[2005-05-24]]|accessdate=2006-06-19}}</ref> However the first 20 years of the 20th century saw an unprecedented rise in the popularity of baseball. Large stadiums dedicated to the game were built for many of the larger clubs or existing grounds enlarged, including [[Shibe Park]], home of the [[Philadelphia Athletics]], [[Ebbets Field]] in [[Brooklyn, New York|Brooklyn]], the [[Polo Grounds]] in [[Manhattan]], [[Boston]]'s [[Fenway Park]] along with [[Wrigley Field]] and [[Comiskey Park]] in [[Chicago, Illinois]]. Likewise from the [[Eastern League]] to the small developing leagues in the West, and the rising [[Negro Leagues]] professional baseball was being played all across the country. Average major league attendances reached a pre [[World War I]] peak of 5,836 in 1909, before falling back during the war. Where there weren't professional teams, there were semi-pro teams, traveling teams [[barnstorming]], company clubs and amateur men's leagues. In the days before television, if you wanted to see a game, you had to go to the game. |

|||

[[File:How to play base ball (IA howtoplaybasebal02murn).pdf|thumb|441x441px|How To Play Baseball instruction book]] |

|||

===The "Black Sox"=== |

|||

[[Image:ShoelessJoeJackson.jpeg|thumb|148px|Shoeless Joe Jackson]] |

|||

As a consequence, home runs were rare, and the "inside game" dominated—singles, [[bunt (baseball)|bunts]], [[stolen base]]s, the hit-and-run play, and other tactics dominated the strategies of the time. |

|||

Contrary to what many of baseball's administrators were willing to acknowledge, gambling was rife in the game. [[Hal Chase]] was particularly notorious for throwing games, but played for a decade after gaining this reputation; he even managed to parlay these accusations into a promotion to manager. Even baseball stars as legendary as [[Ty Cobb]] and [[Tris Speaker]] have been credibly alleged to have fixed game outcomes. The league's complacency during this Golden Age of baseball was shockingly exposed in 1919, in what rapidly became known as the [[Black Sox scandal]]. |

|||

Despite this, there were also several superstar hitters, the most famous being [[Honus Wagner]], held to be one of the greatest [[shortstop]]s to ever play the game, and Detroit's [[Ty Cobb]], the "Georgia Peach." His career [[batting average (baseball)|batting average]] of .366 has yet to be bested. |

|||

During the season the [[Chicago White Sox]] had shown themselves to be the best team in (probably) both leagues, and were the [[bookmaker]]'s favorites to defeat the [[Cincinnati, Ohio|Cincinnati]] club in the [[Baseball/World Series|World Series]]. The White Sox were defeated and throughout the Series rumors were common that the players, motivated by a mixture of greed and a dislike of club owner [[Charles Comiskey]], had taken money to [[match fixing|throw the games]]. During the following seasons the rumours intensified, and spread to other clubs, until a [[grand jury]] was convened to investigate. During the investigation two players, [[Eddie Cicotte]] and [[Shoeless Joe Jackson|"Shoeless" Joe Jackson]] confessed and eight players were tried, and acquitted, for their role in the fix. Much of the evidence (depositions and other testimony) disappeared mysteriously. The Leagues were not so forgiving. Under the commissioner, [[Kenesaw Mountain Landis]], all eight players were banned from organized baseball for life. |

|||

==The |

===The Merkle incident=== |

||

{{Main|Merkle's Boner}} |

|||

==='''A history within a history'''=== |

|||

The [[1908 Major League Baseball season|1908 pennant races]] in both the AL and NL were among the most exciting ever witnessed. The conclusion of the National League season, in particular, involved a bizarre chain of events. On September 23, 1908, the [[1908 New York Giants season|New York Giants]] and [[1908 Chicago Cubs season|Chicago Cubs]] played a game in the [[Polo Grounds III|Polo Grounds]]. Nineteen-year-old rookie first baseman [[Fred Merkle]], later to become one of the best players at his position in the league, was on first base, with teammate Moose McCormick on third with two outs and the game tied. Giants shortstop Al Bridwell socked a single, scoring McCormick and apparently winning the game. However, Merkle, instead of advancing to second base, ran toward the clubhouse to avoid the spectators mobbing the field, which at that time was a common, acceptable practice. The Cubs' second baseman, [[Johnny Evers]], noticed this. In the confusion that followed, Evers claimed to have retrieved the ball and touched second base, forcing Merkle out and nullifying the run scored. Evers brought this to the attention of the umpire that day, Hank O'Day, who after some deliberation called the runner out. Because of the state of the field O'Day thereby called the game. Despite the arguments by the Giants, the league upheld O'Day's decision and ordered the game replayed at the end of the season, if necessary. It turned out that the Cubs and Giants ended the season tied for first place, so the game was indeed replayed, and the Cubs won the game, the pennant, and subsequently the [[1908 World Series|World Series]] (the last Cubs Series victory until 2016). |

|||

For his part, Merkle was doomed to endless ridicule throughout his career (and to a lesser extent for the rest of his life) for this lapse, which went down in history as "[[Merkle's Boner]]". In his defense, some baseball historians have suggested that it was not customary for game-ending hits to be fully "run out", it was only Evers's insistence on following the rules strictly that resulted in this unusual play.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://members.aol.com/Jaybird926/merkle.htm|title=Fred Merkle and the 1908 Giants|access-date=June 19, 2006}}</ref> In fact, earlier in the 1908 season, the identical situation had been brought to the umpires' attention by Evers; the umpire that day was the same Hank O'Day. While the winning run was allowed to stand on that occasion, the dispute raised O'Day's awareness of the rule, and directly set up the Merkle controversy.<ref>{{cite book |last= Murphy|first= Cait|date= 2009|title= Crazy '08, How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History|publisher= Harper, Collins|isbn= 978-0060889388}}{{page needed|date=June 2020}}</ref> |

|||

Until [[July 5]] [[1947]], baseball had two histories. One fills libraries, while baseball historians are only just beginning to chronicle the other fully. |

|||

===New places to play=== |

|||

African Americans have played baseball as long as white Americans. Players of color, both [[African-American]] and [[Hispanic]], played for white baseball clubs throughout the early days of the organizing amateur sport. |

|||

Turn-of-the-century baseball attendances were modest by later standards. The average for the 1,110 games in the [[1901 Major League Baseball season|1901 season]] was 3,247.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kenn.com/sports/baseball/mlb/ml_numbers.html |author=Kenn Tomasch |title=Historical attendance figures for Major League Baseball |date=May 24, 2005 |access-date=June 19, 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060511134344/http://www.kenn.com/sports/baseball/mlb/ml_numbers.html |archive-date=May 11, 2006 |url-status=dead }}</ref> However, the first 20 years of the 20th century saw an unprecedented rise in the popularity of baseball. Large stadiums dedicated to the game were built for many of the larger clubs or existing grounds enlarged, including [[Tiger Stadium (Detroit)|Tiger Stadium]] in [[Detroit]], [[Shibe Park]] in [[Philadelphia]], [[Ebbets Field]] in [[Brooklyn]], the [[Polo Grounds III|Polo Grounds]] in [[Manhattan]], [[Boston]]'s [[Fenway Park]] along with [[Wrigley Field]] and [[Comiskey Park]] in Chicago. Likewise from the [[Eastern League (1938–2020)|Eastern League]] to the small developing leagues in the West, and the rising [[Negro leagues]] professional baseball was being played all across the country. Average major league attendances reached a pre-World War I peak of 5,836 in [[1909 Major League Baseball season|1909]]. Where there weren't professional teams, there were semi-professional teams, traveling teams [[barnstorm (sports)|barnstorming]], company clubs and amateur men's leagues that drew small but fervent crowds. |

|||

===The "Black Sox"=== |

|||

As early as [[1867]], the racism of the post-[[American Civil War|Civil War]] era showed up in the national pastime: The [[National Association of Baseball Players]], an amateur association, voted to exclude any club that had black players from playing with them. |

|||

[[File:ShoelessJoeJackson.jpg|thumb|148px|Shoeless Joe Jackson]] |

|||

{{Main|Black Sox Scandal}} |

|||

The fix of baseball games by gamblers and players working together had been suspected as early as the 1850s.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk2.html |title=History Files – Chicago Black Sox |publisher=Chicagohs.org |date=December 13, 2001 |access-date=March 24, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100317220057/http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk2.html |archive-date=March 17, 2010 }}</ref> [[Hal Chase]] was particularly notorious for throwing games, but played for a decade after gaining this reputation; he even managed to parlay these accusations into a promotion to manager. Even baseball stars such as [[Ty Cobb]] and [[Tris Speaker]] have been credibly alleged to have fixed game outcomes. When MLB's complacency during this "Golden Age" was eventually exposed after the [[1919 World Series]], it became known as the [[Black Sox scandal]]. |

|||

After an excellent regular season (88–52, .629 W%), the [[1919 Chicago White Sox season|Chicago White Sox]] were heavy favorites to win the 1919 World Series. Arguably the best team in baseball, the White Sox had a deep lineup, a strong pitching staff, and a good defense. Even though the National League champion [[1919 Cincinnati Reds season|Cincinnati Reds]] had a superior regular season record (96–44, .689 W%,) no one, including [[gamblers]] and [[bookmaker]]s, anticipated the Reds having a chance. When the Reds triumphed 5–3, many pundits cried foul. |

|||

In [[1871]] the first professional white league formed. [[Bud Fowler]] became their first professional black baseball player, with a non-league pro team in [[1872]]. [[Fleet Walker]] a catcher, appeared in 42 games with the [[Toledo Blue Stockings]] of the [[American Association (19th century)|American Association]] in [[1884]]. |

|||

At the time of the scandal, the White Sox were arguably the most successful franchise in baseball, with excellent gate receipts and record attendance. At the time, most baseball players were not paid especially well and had to work other jobs during the winter to survive. Some elite players on the big-city clubs made very good salaries, but Chicago was a notable exception. |

|||

Yet the racial tensions between white and black people that were present in society showed up on baseball fields. [[Cap Anson]] refused to play in a game with a negro pitcher, [[George Stovey]] at a game in [[1887]]. This was a famous, but hardly isolated incident. |

|||

For many years, the White Sox were owned and operated by [[Charles Comiskey]], who paid the lowest player salaries, on average, in the American League. The White Sox players all intensely disliked Comiskey and his penurious ways, but were powerless to do anything, thanks to baseball's so-called "reserve clause" that prevented players from switching teams without their team owner's consent. |

|||

In that same year, the [[International League]]'s Board of Directors voted against approving any further contracts with black baseball players. While black players continued to find a few jobs in other leagues, the move set into motion racist tendencies that led to the unwritten "gentleman's agreement" a [[Baseball color line|bar on black players]] in both major league and independent baseball clubs affiliated with the [[National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues]]. |

|||

By late 1919, Comiskey's tyrannical reign over the Sox had sown deep bitterness among the players, and White Sox first baseman [[Chick Gandil|Arnold "Chick" Gandil]] decided to conspire to throw the 1919 World Series. He persuaded gambler [[Joseph "Sport" Sullivan]], with whom he had had previous dealings, that the fix could be pulled off for $100,000 total (which would be equal to ${{Formatnum:{{Inflation|US|100000|1919}}}} today), paid to the players involved.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk3.html |title=History Files – Chicago Black Sox |publisher=Chicagohs.org |date=December 13, 2001 |access-date=March 24, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029184407/http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk3.html |archive-date=October 29, 2013 }}</ref> New York gangster [[Arnold Rothstein]] supplied the $100,000 that Gandil had requested through his lieutenant [[Abe Attell]], a former featherweight [[boxing]] champion. |

|||

Black baseball developed its own network of formal, semi-formal and informal pro and semi-pro leagues. The progress of the leagues' development was much slower, because they lacked both the economic resources and the political clout to evolve as rapidly. |

|||

After the 1919 series, and through the beginning of the [[1920 Major League Baseball season|1920 baseball season]], rumors swirled that some of the players had conspired to purposefully lose.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk4a.html |title=History Files – Chicago Black Sox |publisher=Chicagohs.org |date=December 13, 2001 |access-date=March 24, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100317220102/http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk4a.html |archive-date=March 17, 2010 }}</ref> At last, in 1920, a [[grand jury]] was convened to investigate these and other allegations of fixed baseball games.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk5.html |title=History Files – Chicago Black Sox |publisher=Chicagohs.org |date=December 13, 2001 |access-date=March 24, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100317215232/http://www.chicagohs.org/history/blacksox/blk5.html |archive-date=March 17, 2010 }}</ref> Eight players ([[Swede Risberg|Charles "Swede" Risberg]], [[Chick Gandil|Arnold "Chick" Gandil]], [[Shoeless Joe Jackson|"Shoeless" Joe Jackson]], [[Happy Felsch|Oscar "Happy" Felsch]], [[Eddie Cicotte]], [[Buck Weaver|George "Buck" Weaver]], [[Fred McMullin]], and [[Lefty Williams|Claude "Lefty" Williams]]) were indicted and tried for conspiracy. The players were ultimately acquitted. |

|||

The first professional black baseball club, the Cuban Giants, was organized in 1885. More teams sprang up. Sometimes they played in their own small parks. Some major league owners, smelling additional revenue, made deals with black clubs to play in the major league parks on away game days. |

|||

However, the damage to the reputation of the sport of baseball led the team owners to appoint Federal judge [[Kenesaw Mountain Landis]] to be the first [[Commissioner of Baseball]]. His first act as commissioner was to ban the "Black Sox" from professional baseball for life. The White Sox, meanwhile, |

|||

By the early 1890s professional black baseball was foundering, with only one ballclub in operation. Closer to the turn of the 20th century, though, that turned around and leagues began to emerge in two power centers: Chicago and the Midwest and the New York-Pennsylvania corridor. |

|||

would not return to the World Series until 1959, and it was not until their next appearance in 2005 they won the World Series. |

|||

==The Negro leagues== |

|||

In the dead ball era, black clubs were independent, without a real league. They played each other. They played semi-pro teams and barnstorm clubs. Some attempts at formal leagues formed and failed. Generally, each team booked its own schedule. |

|||

{{Main|Negro league baseball}} |

|||

Until July 5, 1947, baseball had two histories. One fills libraries, while baseball historians are only just beginning to chronicle the other fully: African Americans have played baseball as long as white Americans. Players of color, both [[African-American]] and [[Hispanic and Latino Americans|Hispanic]], played for white baseball clubs throughout the very early days of the growing amateur sport. [[Moses Fleetwood Walker]] is considered the first African American to play at the major league level, in 1884. But soon, and dating through the first half of the 20th century, an unwritten but iron-clad [[Baseball color line|color line]] fenced African-Americans and other players of color out of the "majors". |

|||

The [[Negro leagues]] were American professional baseball leagues comprising predominantly African-American teams. The term may be used broadly to include professional black teams outside the leagues and it may be used narrowly for the [[Negro league baseball#Negro major leagues|seven relatively successful leagues beginning 1920]] that are sometimes termed "Negro major leagues". |

|||

[[Rube Foster]], a former ballplayer with a gift for organization, founded the [[Negro National League]] in [[1920]]. A second league, the [[Eastern Colored League]] was established in [[1923]]. These became known as the "[[Negro League baseball|Negro Leagues]]." The [[Negro Southern League]] formed around the same time, but because of its distance from the East-Midwest power centers, and its poor finances, it remained independent and out of the loop from the other leagues. |

|||

The first professional team, established in [[1885 in baseball|1885]], achieved great and lasting success as the [[Cuban Giants]], while the first league, the [[National Colored Base Ball League]], failed in [[1887 in baseball|1887]] after only two weeks due to low attendance. The [[Negro American League]] of [[1951 in baseball|1951]] is considered the last major league season and the last professional club, the [[Indianapolis Clowns]], operated amusingly rather than competitively from the mid-1960s to 1980s. |

|||

From [[1924]] to [[1927]], these two black 'major' leagues held four [[Negro League World Series]]. |

|||

===The first international leagues=== |

|||

The ECL was relatively prosperous but always unstable due to almost perpetual in-fighting amongst its owners. It folded in 1928. In its wake the [[American Negro League]] formed in [[1929]], but disbanded after one season. The surviving Eastern teams went back to the old system of booking games. |

|||

While many of the players that made up the black baseball teams were African Americans, many more were [[Latin Americans]] (mostly, but not exclusively, black), from nations that deliver some of the greatest talents that make up the Major League rosters of today.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Hoh |first1=Anchi |title=Batting 1000: The Influence of Latinos and Latin Americans in MLB |url=https://blogs.loc.gov/international-collections/2018/07/batting-1000-the-influence-of-latinos-and-latin-americans-in-mlb/ |website=The Library of Congress Blogs |date=30 July 2018 }}</ref> Black players moved freely through the rest of baseball, playing in Canadian Baseball, [[Mexican Baseball]], Caribbean Baseball, and Central America and South America, where more than a few achieved a level of fame that was unavailable in the country of their birth. |

|||

==Babe Ruth and the end of the dead-ball era== |

|||

The Negro National League did well until 1930, when Rube Foster suffered a debilitating illness and died. Without a strong leader, the league entered into the [[Great Depression]] and folded, with its surviving franchises returning back to independent team operation. |

|||

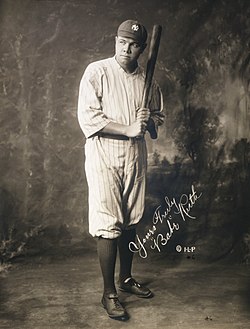

[[File:Babe Ruth2.jpg|right|thumb|250px|[[Babe Ruth]] in 1920.]] |

|||

[[Image:MLB attendance vs population.png|thumb|Graph depicting the yearly MLB attendance versus total U.S. population|250px|right]] |

|||

{{see also|Golden age of baseball}} |

|||

It was not the Black Sox scandal which put an end to the dead-ball era, but a rule change and a single player. |

|||

Some of the increased offensive output can be explained by the 1920 rule change that outlawed tampering with the ball. Pitchers had developed a number of techniques for producing "[[spitball]]s", "shine balls" and other trick pitches which had "unnatural" flight through the air. Umpires were now required to put new balls into play whenever the current ball became scuffed or discolored. This rule change was enforced all the more stringently following the death of [[Ray Chapman]], who was struck in the temple by a pitched ball from [[Carl Mays]] in a game on August 16, 1920; he died the next day. Discolored balls, harder for batters to see and therefore harder for batters to dodge, have been rigorously removed from play ever since. This meant that batters could now see and hit the ball with less difficulty. With the added prohibition on the ball being purposely wetted or scuffed in any way, pitchers had to rely on pure athletic skill—changes in grip, wrist angle, arm angle and throwing dynamics, plus a new and growing appreciation of the aerodynamic effect of the spinning ball's seams—to pitch with altered trajectories and hopefully confuse or distract batters. |

|||

By 1932, the Depression had hit new lows. Unemployment, particularly in the African-American communities, was sky-high. Without money to buy tickets, and without the patronage of white major league baseball, whose contract purchases kept many independent league ballclubs afloat, most of the teams closed, sending players scattering anywhere to find work. Barnstorming tours kept a few employed. The [[East-West League]] folded mid-season of their first year. The [[Negro Southern League]] used to working with less, became the defacto 'major' negro league that year because it could keep major league players playing. Many more players went to Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba and other Latin American nations to find work in places where their skin color would not be an issue. |

|||

At the end of the 1919 season Harry Frazee, then owner of the [[Boston Red Sox]], sold a group of his star players to the [[New York Yankees]]. Among them was [[Babe Ruth|George Herman Ruth]], known affectionately as "Babe". Ruth's career mirrors the shift in dominance from pitching to hitting at this time. He started his career as a pitcher in 1914, and by 1916 was considered one of the dominant left-handed pitchers in the game. When Edward Barrow, managing the Red Sox, converted him to an outfielder, ballplayers and sportswriters were shocked. It was apparent, however, that Ruth's bat in the lineup every day was far more valuable than Ruth's arm on the mound every fourth day. Ruth swatted 29 home runs in his last season in Boston. The next year, as a Yankee, he would hit 54 and in 1921 he hit 59. His 1927 mark of 60 home runs would last until 1961. |

|||

[[Gus Greenlee]] and several others revived the Negro National League in 1933, piecing together teams from both the old NNL and the ECL leagues. As it was one league, the only rivalry between the two sides of it became the [[East-West All-Star]] game. |

|||

[[File:Hank Greenberg 1937 cropped.jpg|thumb |Hall of Famer [[Hank Greenberg]]]] |

|||

In [[1937]] the [[Negro American League]] formed with teams from the Eastern part of the country and survivors of the Negro Southern League as its core. The Negro National League realigned as a more Eastern league as well. The composition of the two began to mirror the white major leagues' structure. From 1942 to 1948 the [[Negro League World Series]] was revived. This was the golden era of Negro League baseball, a time when it produced some of its greatest stars, and when it did so well financially that white baseball sat up and took notice. |

|||

Ruth's power hitting ability demonstrated a dramatic new way to play the game, one that was extremely popular with fans. Accordingly, ballparks were expanded, sometimes by building outfield "bleacher" seating which shrunk the size of the outfield and made home runs more frequent. In addition to Ruth, hitters such as [[Rogers Hornsby]] also took advantage, with Hornsby compiling extraordinary figures for both power and average in the early 1920s. By the late 1920s and 1930s all the good teams had their home-run hitting "sluggers": the Yankees' [[Lou Gehrig]], [[Jimmie Foxx]] in [[Philadelphia]], [[Hank Greenberg]] in [[Detroit]] and in Chicago [[Hack Wilson]] were the most storied. While the American League championship, and to a lesser extent the [[Baseball/World Series|World Series]], would be dominated by the Yankees, there were many other excellent teams in the inter-war years. The National League's [[St. Louis Cardinals]], for example, would win three titles in nine years, the last with a group of players known as the "[[Gashouse Gang]]". |

|||

The [[Major League Baseball on the radio|first radio broadcast]] of a baseball game was on August 5, 1921, over Westinghouse station KDKA from Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Harold Arlin announced the Pirates–Phillies game. Attendances in the 1920s were consistently better than they had been before WWI. The interwar peak average attendance was 8,211 in 1930, but baseball was hit hard by the [[Great Depression]] and in 1933 the average fell below five thousand for the only time between the wars. At first wary of radio's potential to impact ticket sales at the park, owners began to make broadcast deals and by the late 1930s, all teams' games went out over the air. |

|||

Usual references to Branch Rickey's breaking of the color-line make it seem like some sort of Ghandian exercise in liberation. Certainly, from Rickey's [[Methodist]] Midwestern roots, the racism of the sport could not have sat well. More importantly though, the [[Brooklyn Dodgers]]' General Manager was a fierce competitor, a shrewd businessman and an apt showman. He watched the full stadiums at Negro League games. He saw the powerful talents on the field. [[World War II|WWII]] had been a drain on baseball's coffers, as many of their star players went to fight overseas. While post-war enthusiasm for the national pastime was good, Rickey believed that it could be better. Paying customers all had one color: The green of money. |

|||

1933 also saw the introduction of the yearly All-Star game, a mid-season break in which the greatest players in each league play against one another in a hard-fought but officially meaningless demonstration game. In 1936 the [[Baseball Hall of Fame]] in [[Cooperstown, New York]], was instituted and five players elected: [[Ty Cobb]], [[Walter Johnson]], [[Christy Mathewson]], [[Babe Ruth]] and [[Honus Wagner]]. The Hall formally opened in 1939 and, of course, remains open to this day. |

|||

So, with the stroke of his pen Jackie Robinson signed the deal that on July 5, 1947, signaled the end of the Negro Leagues. The full effect was not felt until [[1948]], when stars like [[Satchel Paige]] were signed out from under the black clubs by white baseball clubs. The Negro National League folded again in 1948. Survivors moved to the Negro American League, which continued to play, in one form or another, until 1960. Effectively though, the Negro Leagues ceased to be of 'major' quality after 1948. |

|||

==The war years== |

|||

===Negro league players in history=== |

|||

In 1941, a year which saw the premature death of [[Lou Gehrig]], Boston's great [[left fielder]] [[Ted Williams]] had a batting average over .400—the last time anyone has achieved that feat. During the same season [[Joe DiMaggio]] hit successfully in [[Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak|56 consecutive games]], an accomplishment both unprecedented and unequaled. |

|||

After the United States entered [[World War II]] after the [[attack on Pearl Harbor]], Landis asked [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] whether professional baseball should continue during the war. In the "Green Light Letter", the US president replied that baseball was important to national morale, and asked for more night games so day workers could attend. Thirty-five Hall of Fame members and more than 500 Major League Baseball players served in the war, but with the exception of [[D-Day]], games continued.<ref name="ivice20040606">{{Cite news |url=http://mlb.mlb.com/content/printer_friendly/mlb/y2004/m06/d06/c762644.jsp |title=Berra, baseball have D-Day legacy |last=Ivice |first=Paul |date=2004-06-06 |work=MLB.com |access-date=2018-04-15}}</ref> Both Williams and DiMaggio would miss playing time in the services, with Williams also flying later in the [[Korean War]]. During this period [[Stan Musial]] led the [[St. Louis Cardinals]] to the 1942, 1944 and 1946 World Series titles. The war years also saw the founding of the [[All-American Girls Professional Baseball League]]. |

|||

<!--Please add new information into relevant articles of the series--> |

|||