Electronic color code: Difference between revisions

Wtshymanski (talk | contribs) postage stamp capacitors |

Wtshymanski (talk | contribs) →Transformer wiring color codes: more on transformers and ARRL reference |

||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

== Transformer wiring color codes== |

== Transformer wiring color codes== |

||

Power [[transformer]]s used in North American vacuum-tube equipment often were color-coded to identify the leads. Black was the primary connection, red secondary for the B+ (plate voltage), red with a yellow tracer was the [[center tap]] for the B+ full-wave rectfier winding, brown was the heater voltage for all tubes, |

Power [[transformer]]s used in North American vacuum-tube equipment often were color-coded to identify the leads. Black was the primary connection, red secondary for the B+ (plate voltage), red with a yellow tracer was the [[center tap]] for the B+ full-wave rectfier winding, green or brown was the heater voltage for all tubes, yellow was the filament voltage for the rectifier tube (often a different voltage than other tube heaters). Two wires of each color were provided for each circuit, and polarity was not identified by the color code. |

||

Audio transformers for vacuum tube equipment were coded blue for the finishing lead of the primary, red for the B= lead of the primary, brown for a primary center tap, green for the finishing lead of the secondary, black for grid lead of the secondary, and yellow for a tapped secondary. Each lead had a different color since polarity was more important for these transformers. Intermediate-frequency tuned transformers were coded blue and red for the primary and green and black for the secondary. <ref> Dorbuck 77, page 554 </ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 03:05, 27 October 2009

The electronic color code discussed here is used to indicate the values or ratings of electronic components, very commonly for resistors, but also for capacitors, inductors, and others. A separate code, the 25-pair color code, is used to identify wires in a cable or bundle.

The electronic color code was developed in the early 1920s by the Radio Manufacturer's Association, now part of Electronic Industries Alliance and was published as EIA-RS-279. The current international standard is IEC 60062[1].

Colorbands were commonly used (especially on resistors) because they were easily printed on tiny components, decreasing construction costs. However, there were drawbacks, especially for color blind people. Overheating of a component, or dirt accumulation, may make it impossible to distinguish brown from red from orange. Advances in printing technology have made printed numbers practical for small components, which are often found in modern electronics.

Resistor, capacitor and inductor

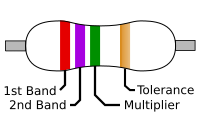

Resistor values are always coded in ohms, capacitors in picofarads (pF), inductors in microhenries (µH), and transformers in volts.

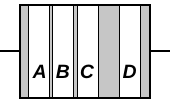

- band A is first significant figure of component value

- band B is the second significant figure

- band C is the decimal multiplier

- band D if present, indicates tolerance of value in percent (no color means 20%)

For example, a resistor with bands of yellow, violet, red, and gold will have first digit 4 (yellow in table below), second digit 7 (violet), followed by 2 (red) zeros: 4,700 ohms. Gold signifies that the tolerance is ±5%, so the real resistance could lie anywhere between 4,465 and 4,935 ohms.

Resistors manufactured for military use may also include a fifth band which indicates component failure rate (reliability); refer to MIL-HDBK-199 for further details.

Tight tolerance resistors may have three bands for significant figures rather than two, and/or an additional band indicating temperature coefficient, in units of ppm/K.

All coded components will have at least two value bands and a multiplier; other bands are optional (italicised below).

The standard color code per EN 60062:2005 is as follows:

| Ring color | Significant figures | Multiplier | Tolerance | Temperature coefficient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Code | RAL[nb 1] | Percent [%] | Letter | [ppm/K] | Letter | |||

| None | – | – | – | – | ±20 | M | – | ||

| Pink | PK | 3015 | – | ×10−3[2] | ×0.001 | – | – | ||

| Silver | SR | – | – | ×10−2 | ×0.01 | ±10 | K | – | |

| Gold | GD | – | – | ×10−1 | ×0.1 | ±5 | J | – | |

| Black | BK | 9005 | 0 | ×100 | ×1 | – | 250 | U | |

| Brown | BN | 8003 | 1 | ×101 | ×10 | ±1 | F | 100 | S |

| Red | RD | 3000 | 2 | ×102 | ×100 | ±2 | G | 50 | R |

| Orange | OG | 2003 | 3 | ×103 | ×1000 | ±0.05[2] | W | 15 | P |

| Yellow | YE | 1021 | 4 | ×104 | ×10000 | ±0.02[2][nb 2][3] | P | 25 | Q |

| Green | GN | 6018 | 5 | ×105 | ×100000 | ±0.5 | D | 20 | Z[nb 3] |

| Blue | BU | 5015 | 6 | ×106 | ×1000000 | ±0.25 | C | 10 | Z[nb 3] |

| Violet | VT | 4005 | 7 | ×107 | ×10000000 | ±0.1 | B | 5 | M |

| Gray | GY | 7000 | 8 | ×108 | ×100000000 | ±0.01[2][nb 4][nb 2][3] | L (A) | 1 | K |

| White | WH | 1013 | 9 | ×109 | ×1000000000 | – | – | ||

As an example, let us take a resistor which (read left to right) displays the colors yellow, violet, yellow, brown. We take the first two bands as the value, giving us 4, 7. Then the third band, another yellow, gives us the multiplier 104. Our total value is then 47 x 104 Ω, totalling 470,000 Ω or 470 kΩ. Our brown is then a tolerance of ±1%.

Resistors use specific values, which are determined by their tolerance. These values repeat for every order of magnitude; 6.8, 68, 680, and so forth. This is useful because the digits, and hence the first two or three stripes, will always be similar patterns of colors, which make them easier to understand.

Zero ohm resistors are manufactured; these are lengths of wire wrapped in a resistor-shaped body which can be substituted for another resistor value in automatic insertion equipment. They are marked with a single black band.[4]

It is sometimes not obvious whether a color coded component is a resistor, capacitor, or inductor, and this may be deduced by knowledge of its circuit function, physical shape or by measurement (capacitors have nearly infinite resistance; unfortunately, so do faulty open-circuit resistors and inductors).

Extra bands on ceramic capacitors will identify the voltage rating class and temperature coefficient characteristics. [5] A broad black band was applied to some tubular paper capacitors to indicate the end that had the outer electrode; this allowed this end to be connected to chassis ground to provide some shielding against hum and noise pickup.

The 'body-end-dot' or 'body-tip-spot' system was used for radial-lead composition resistors sometimes found in vacuum-tube equipment; the first band was given by the body color, the second band by the color of the end of the resistor, and the multiplier by a dot or band around the middle of the resistor. The other end of the resistor was colored gold or silver to give the tolerance, otherwise it was 20%. [6]

Diode part number

The part number for diodes was sometimes also encoded as colored rings around the diode, using the same numerals as for other parts. The JEDEC "1N" prefix was assumed, and the balance of the part number was given by three or four rings.

Postage stamp capacitors and war standard coding

Capacitors of the rectangular 'postage stamp" form made for military use during World War II used American War Standard (AWS) or Joint Army Navy (JAN) coding in six dots stamped on the capacitor. An arrow on the top row of dots pointed to the right, indicating the reading order. From left to right the top dots were: black, indicating JAN mica or silver indicating AWS paper. first and second significant figures. The bottom three dots indicated temperature characteristic, tolerance, and decimal multiplier. The characteristic was black for +/- 1000 ppm/ degree c, brown for 500, red for 200, orange for 100, yellow for -20 to +1-- ppm/ degree c, and green for 0 to +70 ppm/degree C. A similar six-dot code by EIA had the top row as first, second and third significant digits and the bottom row as voltage rating (in hundreds of volts - no color indicated 500 volts), tolerance, and multiplier. A three-dot EIA code was used for 500 volt 20% tolerance capacitors, and the dots signified first and second significant digits and the multiplier. Such capacitors were common in vacuum tube equipment and in surplus for a generation after the war but are unavailable now. [7]

Mnemonics

A useful mnemonic for remembering the first ten color codes matches the first letter of the color code, by order of increasing magnitude. There are many variations:

- Boys better remember our young girls become very good wives.. BYU Engineering Department

- Bad boys rape our young girls behind victory garden walls.[8][9]

- Bad boys run our young girls behind victory garden walls.[10]

- Bad boys rape our young girls but Violet gives willingly.[8][9]

- Big boys race our young girls but Violet generally wins.[11]

The tolerance codes, gold, silver, and none, are not usually included in the mnemonics; one extension that includes them is:

- Bad beer rots our young guts but vodka goes well – get some now.[12]

Since B can stand for both "black" and "brown", variations are formed such as "Black boys rape our young girls...".[10]

Humorous, offensive, or sexual mnemonics are more memorable (see mnemonic), but these variations are often considered inappropriate for classrooms, and have been implicated as a sign of sexism in science and engineering classes.[13] Dr. Latanya Sweeney, associate professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon, a black woman, mentions the mnemonic ("black boys rape only young girls but Violet gives willingly") as one of the reasons she felt alienated and eventually dropped out of MIT in the 1980s to form her own software company.[14][15]

A politically-correct mnemonic that has attained some traction in recent years is:

Another mnemonic that is not offensive and can be used in the classroom is:

Other mnemonics commonly taught in UK engineering courses include:

- Bye Bye Rosie Off You Go Birmingham Via Great Western[22]

- Bye Bye Rosie Off You Go Bristol Via Great Western[23]

- Bye Bye Rosie Off You Go But Via Great Western

- Bye Bye Rosie Off You Go do Become a Very Good Wife[21]

The colors are sorted in the order of the visible light spectrum: red (2), orange (3), yellow (4), green (5), blue (6), violet (7). Black (0) has no energy, brown (1) has a little more, white (9) has everything and grey (8) is like white, but less intense.[25]

Examples

From top to bottom:

- Green-Blue-Brown-Black-Brown

- 561 Ω ± 1%

- Red-Red-Orange-Gold

- 22,000 Ω ± 5%

- Yellow-Violet-Brown-Gold

- 470 Ω ± 5%

- Blue-Gray-Black-Silver

- 68 Ω ± 10%

Not pictured:

- Brown-Black-Brown

- 100 Ω ± 20%

- Black

- zero Ω

Note: The physical size of a resistor is indicative of the power it can dissipate, not of its resistance.

Printed numbers

Color-coding of this form is becoming rarer. In newer equipment, most passive components come in surface mount packages. Many of these packages are unlabeled, and those that are normally use alphanumeric codes, not colors.

In one popular marking method, the manufacturer prints 3 digits on components: 2 value digits followed by the power of ten multiplier. Thus the value of a resistor marked 472 is 4,700 Ω, a capacitor marked 104 is 100 nF (10x104 pF), and an inductor marked 475 is 4.7 H (4,700,000 µH). This can be confusing; a resistor marked 270 might seem to be a 270 Ω unit, when the value is actually 27 Ω (27×100). Another way is to use the "kilo-" or "mega-" prefixes in place of the decimal point:

- 1K2 = 1.2 kΩ = 1,200 Ω

- M47 = 0.47 MΩ = 470,000 Ω

- 68R = 68 Ω

For 1% resistors, a three-digit alphanumeric code is sometimes used, which is not obviously related to the value but can be derived from a table of 1% values. For instance, a resistor marked 68C is 499(68) × 100(C) = 49,900 Ω. In this case the value 499 is the 68th entry of a table of 1% values between 100 and 999.

Transformer wiring color codes

Power transformers used in North American vacuum-tube equipment often were color-coded to identify the leads. Black was the primary connection, red secondary for the B+ (plate voltage), red with a yellow tracer was the center tap for the B+ full-wave rectfier winding, green or brown was the heater voltage for all tubes, yellow was the filament voltage for the rectifier tube (often a different voltage than other tube heaters). Two wires of each color were provided for each circuit, and polarity was not identified by the color code.

Audio transformers for vacuum tube equipment were coded blue for the finishing lead of the primary, red for the B= lead of the primary, brown for a primary center tap, green for the finishing lead of the secondary, black for grid lead of the secondary, and yellow for a tapped secondary. Each lead had a different color since polarity was more important for these transformers. Intermediate-frequency tuned transformers were coded blue and red for the primary and green and black for the secondary. [26]

See also

- 25-pair color code for wiring

- Other color codes

References

- ^ IEC 60062 Title: "Marking codes for resistors and capacitors" (IEC Webstore)

- ^ a b c d "IEC 60062:2016-07" (6 ed.). July 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-07-23. [1]

- ^ a b VR37 High ohmic/high voltage resistors (PDF). Vishay. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-10.

- ^ NIC Components Corp. NZO series zero-ohm resistors.

- ^ Reference Data for Radio Engineers,Federal Telephone and Radio Corporation, 2nd edition, 1946 page 52

- ^ Reference Data for Radio Engineers, page 52

- ^ Tony Dorbuck (ed),The Radio Amateur's Handbook Fifty Fifth (1978 edition), The American Radio Relay Leaague, Connecticut 1977 , no ISBN, Library of congress card no. 41-3345, page 553

- ^ a b Booker, M. Keith (1993). Literature and Domination: Sex, Knowledge, and Power in Modern Fiction. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0813011957.

- ^ a b Pynchon, Thomas (1999). V. HarperCollins. p. 560. ISBN 0060930217.

- ^ a b Indiana University. Midwest Folklore (v.10-11 1960-1961 ed.).

- ^ Meade, Russell L. (2004). Foundations of Electronics: Circuits and Devices. Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 1401859763.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Mnemonics Page - Dean Campbell, Bradley University Chemistry Department

- ^ Morse, Mary (2001). Women Changing Science: Voices from a Field in Transition. Basic Books. p. 308. ISBN 0738206156.

- ^ Roth, Mark (2005-12-26). "The Thinkers: Data privacy drives CMU expert's work". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Walter, Chip (2007-06-27). "Privacy Isn't Dead, or At Least It Shouldn't Be: A Q&A with Latanya Sweeney". Scientific American. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Benjamin W. Niebel and Andris Freivalds (2003). Methods, Standards, and Work Design (eleventh ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 297. ISBN 9780072468243.

- ^ Jack Ganssle (2004). The Firmware Handbook. Elsevier. p. 10. ISBN 9780750676069.

- ^ Jack G. Ganssle, Tammy Noergaard, Fred Eady, Lewin Edwards, David J. Katz, Rick Gentile, Ken Arnold, Kamal Hyder, and Bob Perrin (2008). Embedded Hardware: Know It All. Newnes. p. 17. ISBN 9780750685849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Various. Xam Idea - Physics. VK Publications. p. 78. ISBN 9788188597659.

- ^ Satya Prakash. Physics Vol (1 and 2). VK Publications. p. 254. ISBN 9788188597314.

- ^ a b S.M., Dhir (1999). "Passive Components". Electronic Components and Materials: Principles Manufacture & Maintenance. India: Tata Mcgraw-Hill. p. 68. ISBN 0-07-463082-2.

- ^ Sinclair, Ian (2002-03-20). "Resistors, networks and measurements". Electronic and Electrical Servicing: Level 2. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Newnes. p. 44. ISBN 0-7506-5423-6.

- ^ a b Bhargava, N.N.; Kulshreshtha, D.C.; Gupta, S.C. (1984-01-01). "Introduction to Electronics". Basic Electronics and Linear Circuits. India: Tata Mcgraw-Hill. p. 8. ISBN 0-07-451965-4.

- ^ Gambhir, R.S. (1993). "DC Circuits". Foundations Of Physics. Vol. 2. India: New Age International. p. 49. ISBN 81-224-0523-1.

- ^ Preston R. Clement and Walter Curtis Johnson (1960). Electrical Engineering Science. McGraw-Hill. p. 115.

- ^ Dorbuck 77, page 554

External links

- IEC 60062 (IEC Webstore)

- 5-band Resistor Color Code Calculator

- Resistor color code calculator (Used to explore E-ranges and color codes.)

- Guide to SMD resistor codes, including alphanumeric codes

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).