Homer

This article or section appears to contradict itself. |

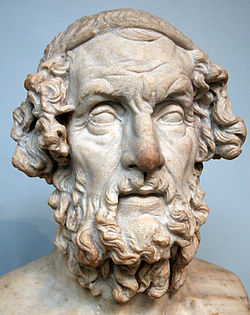

Idealized portrayal of Homer dating to the Hellenistic period. British Museum. | |||

| Pen name |

| ||

| Nationality | Greek | ||

| Period | Archaic Greece | ||

| Genre | Epic poetry | ||

Homer (ancient Greek: Ὅμηρος, Homēros) is an ancient Greek epic poet, traditionally considered the author of the epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey. No reliable biographical information about Homer survives from classical antiquity, and he is considered a legendary figure rather than a historical person.[verification needed][unbalanced opinion?] The Iliad and the Odyssey are considered by most scholars to be the products of a centuries-long tradition of orally composed poetry; the role of an individual poet, or poets, in composing them is a matter of dispute. According to some, they are the product of the same poet, but for others, such as Martin West, they were composed by different poets. For still others, such as Gregory Nagy, the epics are not the creation of any individual, but rather slowly evolved towards their final form over a period of centuries; in this view, they are the collective work of generations of poets.

Homer's works begin the Western Canon and are universally praised for their poetic genius. By convention, the compositions are also often taken to initiate the period of Classical Antiquity.

Identity and authorship

Biographical problems

Even if a single author was responsible for the two major epics ascribed to Homer, nothing is known of him for certain. There is no indisputable evidence that such a person ever existed. Many passages in archaic and classical Greek poetry and prose mention Homer or allude to him, and the ten preserved Lives of Homer purport to give the poet's birthplace and background. Due to the contradictory, diverse and legendary or semi-legendary character of these accounts, they give no solid evidence on which to base a theory of Homer's identity.[2] For example, when the Emperor Hadrian asked the Oracle at Delphi who Homer really was, the Pythia proclaimed that he was Ithacan, the son of Epikaste and Telemachus, from the Odyssey,[3] despite the long tradition that Homer was from Ionia, more specifically from Smyrna, for which reason he is sometimes referred to as Melesigenes "born of Meles".[citation needed][vague] Speaking a thousand years after his time, on what tradition did she rely, the written records kept by the temple, her political advisors or her drug-induced ravings? The rest of the evidence is no less problematic.

A number of traditions hold that he was blind (perhaps because, in the Aeolian dialect of Cyme, homēros bore this meaning)[4] and that he was born on the island of Chios, at Smyrna or elsewhere in Ionia, where various cities vied in claiming him as one of their native sons. The characterization of Homer as a blind bard is supported by a possibly self-referential passage in the Odyssey in which a shipwrecked Odysseus listens to the tales of a blind bard named Demodocus while in the court of the Phaeacian king.[5] Template:Details3

Problems of authorship

A long-standing issue is whether the same poet was responsible for both the Iliad and the Odyssey. While many find it unlikely that the Odyssey was written by one person, others find that the epic is generally in the same style, and too consistent to support the theory of multiple authors. A further view is that the Iliad was composed by 'Homer' in his maturity, and the Odyssey was a work of his old age. The Batrachomyomachia, Homeric Hymns, and cyclic epics are generally agreed to be later than the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Homer was even at one time credited with the entire Epic Cycle. The genre included further poems on the Trojan War as well as the Theban poems about Oedipus and his sons. Other works, such as the corpus of Homeric Hymns, the comic mini-epic Batrachomyomachia ("The Frog-Mouse War", Βατραχομυομαχία), and the Margites were also attributed to him, but this is now believed to be unlikely. Several other epics, such as the Cypria, the Little Iliad, the Phocais, the Thebais, and the Capture of Oechalia were said to have been written by Homer in classical sources. However, it is likely that the question of the identity of the author of these stories is similarly problematic.[6]

Most scholars agree that the Iliad and Odyssey underwent a process of standardization and refinement out of older material beginning in the 8th century BCE. An important role in this standardization appears to have been played by the Athenian tyrant Hipparchus, who reformed the recitation of Homeric poetry at the Panathenaic festival. Many classicists hold that this reform must have involved the production of a canonical written text.[citation needed]

This article has an unclear citation style. |

Other scholars, however, still[vague] support the idea that Homer was a real person. Since nothing is known of the life of this Homer, the common joke, often recycled also in disputes about the authorship of plays ascribed to Shakespeare, has it that the poems "were not written by Homer, but by another man of the same name,"[1][2]. Samuel Butler argued that a young Sicilian woman wrote the Odyssey (but not the Iliad), an idea further pursued by Robert Graves in his novel Homer's Daughter and Andrew Dalby in Rediscovering Homer.

Independently of the question of single authorship, it is agreed universally, after the work of Milman Parry[7] that the Homeric poems are the product of an oral tradition, a generations-old technique that was the collective inheritance of many singer-poets (aoidoi). An analysis of the structure and vocabulary of the Iliad and Odyssey shows that the poems consist of formulaic phrases typical of extempore epic traditions; even entire verses are at times repeated. Milman Parry and his student Albert Lord pointed out that such elaborate oral tradition, foreign to today's literate cultures, is typical of epic poetry in a predominantly oral cultural milieu. The crucial words are "oral" and "traditional". Parry started with "traditional". The repetitive chunks of language, he said, were inherited by the singer-poet from his predecessors, and they were useful to the poet in composition. He called these chunks of repetitive language "formulas".

Exactly when these poems would have taken on a fixed written form is subject to debate. The traditional solution is the "transcription hypothesis", wherein a non-literate "Homer" dictates his poem to a literate scribe between the 8th and 6th centuries. The Greek alphabet was introduced in the early 8th century, so that it is possible that Homer himself was of the first generation of rhapsodes that were also literate. More radical Homerists, such as Gregory Nagy, contend that a canonical text of the Homeric poems as "scripture" did not exist until the Hellenistic period (3rd to 1st century BCE).

Homeric studies

The study of Homer is one of the oldest topics in scholarship, dating back to antiquity. It is one of the largest of all literary sub-disciplines: the annual publication output rivals that of Shakespeare. The aims and achievements of Homeric studies have changed over the course of the millennia; in the last few centuries they have revolved around the process by which the Homeric poems came into existence and were transmitted down to us, first orally, and later in writing.

Some of the main trends in modern Homeric scholarship have been, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Analysis and Unitarianism (see Homeric question), which were schools of thought that emphasized on the one hand the inconsistencies, on the other the artistic unity, in Homer; and in the 20th century and later Oral Theory, which is the study of the mechanisms and effects of oral transmission, and Neoanalysis, which is the study of the relationship between Homer and other early epic material. Many people believe that Homer learned his material from story telling, and then he wrote it down in his two epics.

Homeric dialect

The language used by Homer is an archaic version of Ionic Greek, with admixtures from certain other dialects, such as Aeolic Greek. It later served as the basis of Epic Greek, the language of epic poetry, typically in dactylic hexameter.

Homeric style

The cardinal qualities of the style of Homer have been well articulated by Matthew Arnold: "the translator of Homer," he says, "should above all be penetrated by a sense of the four qualities of his author: that he is eminently rapid; that he is eminently plain and direct, both in the evolution of his thought and in the expression of it, that is, both in his syntax and in his words; that he is eminently plain and direct in the substance of his thought, that is, in his matter and ideas; and finally, that he is eminently noble" (On Translating Homer, page 9).

The peculiar rapidity of Homer is due in great measure to his use of the hexameter verse. It is characteristic of early literature that the evolution of the thought, or the grammatical form of the sentence, is guided by the structure of the verse; and the correspondence which consequently obtains between the rhythm and the syntax, the thought being given out in lengths, as it were, and these again divided by tolerably uniform pauses produces a swift flowing movement, such as is rarely found when the periods have been constructed without direct reference to the metre. That Homer possesses this rapidity without falling into the corresponding faults, that is, without becoming either fluctuant or monotonous, is perhaps the best proof of his unequalled poetical skill. The plainness and directness, both of thought and of expression, which characterize Homer were doubtless qualities of his age; But the author of the Iliad (similar to Voltaire, to whom Arnold happily compares him) must have possessed this gift in a surpassing degree. The Odyssey is in this respect perceptibly below the level of the Iliad.

Rapidity or ease of movement, plainness of expression, and plainness of thought are not the distinguishing qualities of the great epic poets, Virgil, Dante, and Milton (Dante in fact mentions Homer in Inferno IV,88, ranking him as 'Poet sovereign' just above Horace, Ovid and Virgil). On the contrary, they belong rather to the humbler epico-lyrical school for which Homer has been so often claimed. The proof that Homer does not belong to that school, and that his poetry is not in any true sense ballad-poetry is furnished by the higher artistic structure of his poems, and, as regards style by the fourth of the qualities distinguished by Arnold, the quality of nobleness. It is his noble and powerful style, sustained through every change of idea and subject, that finally separates Homer from all forms of ballad-poetry and popular epic.

Like the French epics, such as the Chanson de Roland, Homeric poetry is indigenous, and by the ease of movement and its resulting simplicity, is distinguishable from the works of Dante, Milton, and Virgil. It is also distinguished from the works of these artists by the comparative absence of underlying motives or sentiment. In Virgil's poetry a sense of the greatness of Rome and Italy is the leading motive of a passionate rhetoric, partly veiled by the chosen delicacy of his language. Dante and Milton are still more faithful exponents of the religion and politics of their time. Even the French epics display sentiments of fear and hatred of the Saracens; but in Homer's works, the interest is purely dramatic. There is no strong antipathy of race or religion; the war turns on no political event; the capture of Troy lies outside the range of the Iliad, and even the heroes portrayed are not comparable to the chief national heroes of Greece. So far as can be seen, the chief interest in Homer's works is that of human feeling and emotion, and of drama - indeed, Homer's works are often referred to as 'dramas'.

History and the Iliad

Another significant question regards the possible historical basis of the poems. The commentaries on the Iliad and the Odyssey written in the Hellenistic period began exploring the textual inconsistencies of the poems. Modern classicists continue the tradition.

The excavations of Heinrich Schliemann in the late 19th century began to provide evidence to scholars that there was a historical basis for the Trojan War. Research (pioneered by the aforementioned Parry and Lord) into oral epics in Serbo-Croatian and Turkic languages began to convince scholars that long poems could be preserved with consistency by oral cultures until they are written down.[7] The decipherment of Linear B in the 1950s by Michael Ventris (and others) convinced others of a linguistic continuity between 13th century BC Mycenaean writings and the poems attributed to Homer.

It is probable, therefore, that the story of the Trojan War as reflected in the Homeric poems derives from a tradition of epic poetry founded on a war which actually took place. However, it is crucial not to underestimate the creative and transforming power of subsequent tradition: for instance, Achilles, the most important character of the Iliad, is strongly associated with southern Thessaly, but his legendary figure is interwoven into a tale of war whose kings were from the Peloponnese. Tribal wanderings were frequent, and far-flung, ranging over much of Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean.[8] The epic manages to weave brilliantly the disiecta membra of these distinct tribal narratives, exchanged among clan bards, into a monumental tale in which Greeks join collectively to do battle on the distant plains of Troy.

Hero cult

In the Hellenistic period, Homer was the subject of a hero cult in several cities. A shrine devoted to Homer or Homereion was built in Alexandria by Ptolemy IV Philopator in the late 3rd century BC. This shrine is described in Aelian's 3rd century work Varia Historia. He described how Ptolemy had "placed in a circle around the statue [of Homer] all the cities who laid claim to Homer" and mentions a painting of the poet by the artist Galaton, which apparently depicted Homer in the aspect of Oceanus as the source of all poetry.

A marble relief, found in Italy but thought to have been sculpted in Egypt, depicts the apotheosis of Homer. It shows Ptolemy and his wife/sister Arsinoe III standing beside a seated Homer. The poet is shown flanked by figures from the Odyssey and Iliad, with the nine Muses standing above them and a procession of worshippers approaching an altar, believed to represent the Alexandrine Homereion. Apollo, god of music and poetry, also appears, along with a female figure tentatively identified as Mnemosyne, the mother of the Muses. Zeus, the king of the gods, presides over the proceedings. The relief demonstrates vividly how the Greeks considered Homer not just a great poet, but the divinely inspired source of all literature.[9]

Homereia also stood at Chios, Ephesus and Smyrna, which were among the city-states that claimed to be the birthplace of Homer. Strabo (14.1.37) records a Homeric temple in Smyrna with an ancient xoanon or cult statue of the poet. He also mentions sacrifices carried out to Homer by the inhabitants of Argos, presumably at another Homereion.[10]

Publication history

In late antiquity knowledge of Greek declined in Latin-speaking western Europe, and along with it knowledge of Homer's poems. It is not until the fifteenth century that Homer's work began to be read once more in Italy. The first printed edition appeared in 1488.

See also

Homeric topics

Works ascribed to Homer

Notable Homeric Scholars

|

References

- ^ Kirk, G.S. (1965). Homer and the Epic: A Shortened Version of the Songs of Homer. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. Part VII, Chapter 18, pages 197-201. Kirk bases his date, which is that of the Iliad, on "the appearance of Trojan-cycle representation and heroic cult at the end of the 8th or beginning of the 7th century...."

- ^ a b Kirk, G.S. (1965). Homer and the Epic: A Shortened Version of the Songs of Homer. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. Part VII, Chapter 18, page 190.

- ^ Parke, Herbert W. (1967). Greek Oracles. pp. pages 136-137 citing the Certamen, 12.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Pseudo-Herodotus, Vita Homeri

- ^ Unknown author. "Homer". Read Print.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) Republished from the Encyclopedia of World Biography. The reasoning is long-standing and in good standing. - ^ Homer - Books and Biography. http://www.readprint.com/author-47/-Homer.

- ^ a b Adam Parry (ed) The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1987

- ^ Gilbert Murray, The Rise of the Greek Epic, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1907 pp.182f., slightly expanded in the 4th.ed.(1934) 1960 pp.206ff.

- ^ Morgan, Llewelyn, 1999. Patterns of Redemption in Virgil's Georgics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 30.

- ^ Zanker, Paul, 1996. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, Alan Shapiro, trans. (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Selected bibliography

Editions

(texts in Homeric Greek)

- Demetrius Chalcondyles editio princeps, Florence, 1488

- the Aldine editions (1504 and 1517)

- Th. Ridel, Strassbourg, ca. 1572, 1588 and 1592.

- Wolf (Halle, 1794-1795; Leipzig, 1804 1807)

- Spitzner (Gotha, 1832-1836)

- Bekker (Berlin, 1843; Bonn, 1858)

- La Roche (Odyssey, 1867-1868; Iliad, 1873-1876, both at Leipzig)

- Ludwich (Odyssey, Leipzig, 1889-1891; Iliad, 2 vols., 1901 and 1907)

- W. Leaf (Iliad, London, 1886-1888; 2nd ed. 1900-1902)

- W. Walter Merry and James Riddell (Odyssey i.-xii., 2nd ed., Oxford, 1886)

- Monro (Odyssey xiii.-xxiv. with appendices, Oxford, 1901)

- Monro and Allen (Iliad), and Allen (Odyssey, 1908, Oxford).

- D.B. Monro and T.W. Allen 1917-1920, Homeri Opera (5 volumes: Iliad = 3rd edition, Odyssey = 2nd edition), Oxford. ISBN 0-19-814528-4, ISBN 0-19-814529-2, ISBN 0-19-814531-4, ISBN 0-19-814532-2, ISBN 0-19-814534-9

- H. van Thiel 1991, Homeri Odyssea, Hildesheim. ISBN 3-487-09458-4, 1996, Homeri Ilias, Hildesheim. ISBN 3-487-09459-2

- M.L. West 1998-2000, Homeri Ilias (2 volumes), Munich/Leipzig. ISBN 3-598-71431-9, ISBN 3-598-71435-1

- P. von der Mühll 1993, Homeri Odyssea, Munich/Leipzig. ISBN 3-598-71432-7

- Ilias in Wikisource

Interlinear translations

- John Jackson. Homer: Iliad Books 1-12, & 13-24, ed. by Monro, 3rd Ed.: © Oxford Univ. Press 1902, parsing and English definitions © 2005 Free eBook for Palm Handheld

- John Jackson. Homer: Odyssey © Oxford Univ. Press 1902, parsing and English definitions © 2006 Free eBook for Palm Handheld

English translations

This is a partial list of translations into English of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.

- Augustus Taber Murray (1866-1940)

- Homer: Iliad, 2 vols., revised by William F. Wyatt, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press (1999).

- Homer: Odyssey, 2 vols., revised by George E. Dimock, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press (1995).

- Robert Fitzgerald (1910–1985)

- The Iliad, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2004) ISBN 0-374-52905-1

- The Odyssey, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1998) ISBN 0-374-52574-9

- Robert Fagles (b. 1933)

- The Iliad, Penguin Classics (1998) ISBN 0-14-027536-3

- The Odyssey, Penguin Classics (1999) ISBN 0-14-026886-3

- Stanley Lombardo (b. 1943)

- Iliad, Hackett (1997) ISBN 0-87220-352-2

- Odyssey, Hackett (2000) ISBN 0-87220-484-7

- Iliad, (Audiobook) Parmenides (2006) ISBN 1-930972-08-3

- Odyssey, (Audiobook) Parmenides (2006) ISBN 1-930972-06-7

- The Essential Homer, (Audiobook) Parmenides (2006) ISBN 1-930972-12-1

- The Essential Iliad, (Audiobook) Parmenides (2006) ISBN 1-930972-10-5

General works on Homer

- J. Latacz 2004, Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-926308-6; 5th updated and expanded edition, Leipzig 2005 (in Spanish 2003 ISBN 84-233-3487-2, modern Greek 2005 ISBN 960-16-1557-1)

- Robert Fowler (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Homer, CUP, Cambridge 2004. ISBN 0-521-01246-5

- I. Morris and B. B. Powell 1997, A New Companion to Homer, Leiden. ISBN 90-04-09989-1

- B. B. Powell 2007, "Homer," 2nd edition. Oxford. ISBN 978-1-4051-5325-5

- Wace, A.J.B. (1962). A Companion to Homer. London. ISBN 0-333-07113-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Influential readings and interpretations

- E. Auerbach 1953, Mimesis, Princeton (orig. publ. in German, 1946, Bern), chapter 1. ISBN 0-691-11336-X

- M.W. Edwards 1987, Homer, Poet of the Iliad, Baltimore. ISBN 0-8018-3329-9

- B. Fenik 1974, Studies in the Odyssey, Wiesbaden ('Hermes' Einzelschriften 30).

- I.J.F. de Jong 1987, Narrators and Focalizers, Amsterdam/Bristol. ISBN 1-85399-658-0

- G. Nagy 1980, "The Best of the Achaeans", Baltimore. ISBN 978-0801860157

Commentaries

- Iliad:

- P.V. Jones (ed.) 2003, Homer's Iliad. A Commentary on Three Translations, London. ISBN 1-85399-657-2

- G. S. Kirk (gen. ed.) 1985-1993, The Iliad: A Commentary (6 volumes), Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-28171-7, ISBN 0-521-28172-5, ISBN 0-521-28173-3, ISBN 0-521-28174-1, ISBN 0-521-31208-6, ISBN 0-521-31209-4

- J. Latacz (gen. ed.) 2002-, Homers Ilias. Gesamtkommentar. Auf der Grundlage der Ausgabe von Ameis-Hentze-Cauer (1868-1913) (2 volumes published so far, of an estimated 15), Munich/Leipzig. ISBN 3-598-74307-6, ISBN 3-598-74304-1

- N. Postlethwaite (ed.) 2000, Homer's Iliad: A Commentary on the Translation of Richmond Lattimore, Exeter. ISBN 0-85989-684-6

- M.W. Willcock (ed.) 1976, A Companion to the Iliad, Chicago. ISBN 0-226-89855-5

- Odyssey:

- A. Heubeck (gen. ed.) 1990-1993, A Commentary on Homer's Odyssey (3 volumes; orig. publ. 1981-1987 in Italian), Oxford. ISBN 0-19-814747-3, ISBN 0-19-872144-7, ISBN 0-19-814953-0

- P. Jones (ed.) 1988, Homer's Odyssey: A Commentary based on the English Translation of Richmond Lattimore, Bristol. ISBN 1-85399-038-8

- I.J.F. de Jong (ed.) 2001, A Narratological Commentary on the Odyssey, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-46844-2

Trends in Homeric scholarship

- "Classical" analysis

- A. Heubeck 1974, Die homerische Frage, Darmstadt. ISBN 3-534-03864-9

- R. Merkelbach 1969, Untersuchungen zur Odyssee (2nd edition), Munich. ISBN 3-406-03242-7

- D. Page 1955, The Homeric Odyssey, Oxford.

- U. von Wilamowitz-Möllendorff 1916, Die Ilias und Homer, Berlin.

- F.A. Wolf 1795, Prolegomena ad Homerum, Halle. Published in English translation 1988, Princeton. ISBN 0-691-10247-3

- Neoanalysis

- M.E. Clark 1986, "Neoanalysis: a bibliographical review," Classical World 79.6: 379-94.

- J. Griffin 1977, "The epic cycle and the uniqueness of Homer," Journal of Hellenic Studies 97: 39-53.

- J.T. Kakridis 1949, Homeric Researches, London. ISBN 0-8240-7757-1

- W. Kullmann 1960, Die Quellen der Ilias (Troischer Sagenkreis), Wiesbaden. ISBN 3-515-00235-9

- Homer and oral tradition

- E. Bakker 1997, Poetry in Speech: Orality and Homeric Discourse, Ithaca NY. ISBN 0-8014-3295-2

- J.M. Foley 1999, Homer's Traditional Art, University Park PA. ISBN 0-271-01870-4

- G.S. Kirk 1976, Homer and the Oral Tradition, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-21309-6

- A.B. Lord 1960, The Singer of Tales, Cambridge MA. ISBN 0-674-00283-0

- M. Parry 1971, The Making of Homeric Verse, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-520560-X

- B. B. Powell, 1991, "Homer and the Origin of the Greek Alphabet," ISBN 0-521-58907-X

Dating the Homeric poems

- R. Janko 1982, Homer, Hesiod and the Hymns, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-23869-2