Makasar script

| Jangang-jangang 𑻪𑻢𑻪𑻢 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 17-19 AD |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Makassarese language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Balinese Batak Baybayin scripts Javanese Lontara Old Sundanese Rencong Rejang |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Maka (366), Makasar |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Makasar |

| U+11EE0–U+11EFF | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Makasar Script, also known as Ukiri' Jangang-jangang (bird's script) or old Makasar script, is a historical Indonesian Writing system that was used in South Sulawesi to write Makassarese language between 17 M and 19 M until it was supplanted by Lontara Bugis.[1][2]

Makasar script is an abugida which consists of 18 basic characters. Like other Brahmi script, each letter represents a syllable with an inherent vowel /a/ which can be changed with diacritics. The direction of writing is left to right. This script is written without spaces between words (scriptio continua) with little to no punctuation. "Dead syllables", or syllables that end in a consonant, are not written in the Makasar script, so any Makasar text can have a lot of ambiguity which can only be distinguished from context.

History

Scholars generally believe that the Makassar script was used before South Sulawesi received significant Islamic influence around the 16th century AD, based on the fact that Makassar script uses the abugida system based on the Brahmi script rather than the Arabic script which became commonplace in South Sulawesi later on.[3] This script has its roots in the Brahmi script from southern India, possibly brought to Sulawesi through Kawi script or other script derived from Kawi.[4][5][6] The visual similarity of the South Sumatran characters such as the Rejang script and the Makassar script has led some experts to suggest a relationship between the two scripts.[7] A similar theory is also elaborated by Christopher Miller who argues that the script of South Sumatra, South Sulawesi, and the Philippines developed in parallel with the Gujarati script, India.[8]

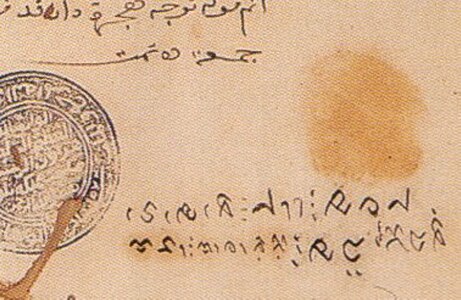

There are at least four writing systems that have been documented to have been used in South Sulawesi, which are, chronologically, Makassar script, Lontara script, Arabic script, and Latin script. In its development, these four writing systems are often used together depending on the context of the writing, so it is common to find a manuscript that uses more than one script, including Makassar script which is often found mixed with Malay Arabic.[9] The Makassar script was originally thought to be the ancestor of the Lontara script, but both are now considered separate branches of an ancient prototype that is assumed extinct.[10] Some writers sometimes mention Daeng Pamatte', the 'syahbandar' of the Sultanate of Gowa in the early 16th century AD, as the creator of the Makassar script based on a quote in the Gowa Chronicle (Makassarese: Lontara Patturioloanga ri Tu Gowaya) which reads Daeng Pamatte' ampareki lontara' Mangkasaraka, translated as "Daeng Pamatte' which created the Makassarese Lontara" in the translation of GJ Wolhoff and Abdurrahim published in 1959. However, this opinion is rejected by most historians and linguists today, who argue that the term ampareki in this context is more accurately translated as "composing" in the sense of compiling a library or completing historical records and writing system instead of script creation from nil.[11][12][13][14] The oldest surviving Makassar script is the signature of the delegates from the Sultanete of Gowa in the Treaty of Bongaya from 1667 which is now stored in the National Archives of Indonesia. Meanwhile, one of the earliest manuscripts in Makassar script of significant length that has survived is the Gowa-Tallo chronicle from the mid 18th century AD which is kept at the Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen (KIT), Amsterdam (collection no. KIT 668/216).[15]

Eventually, the use of the Makassar script was gradually replaced by Lontara Bugis script which for Makassarese writers is sometimes referred to as "new lontara". This change was likely influenced by the decline in the prestige of the Sultanete of Gowa along with the increasing strength of the Buginese tribe. As the influence of Gowa decreased, the Makassar scribes no longer use Makassar script in official historical records or everyday documents, although it was still sometimes used for certain contexts as an attempt to distinguish Makassar's cultural identity from Bugis influence. The most recent manuscript with Makassar script so far known is the diary of a Gowa tumailalang (prime minister) from the 19th century whose script form has received significant influence from the Lontara Bugis script.[16] By the end of the 19th century, the use of Makassar script had been completely replaced by Lontara Bugis and nowadays there are no more native readers of Makassar script. [1]

Usage

| Penggunaan Aksara Makassar | |

|

Like the Lontara script which was used in the South Sulawesi cultural sphere, Makasar script is used in a number of related text traditions, most of which are written in manuscripts. The term lontara (sometimes spelled lontaraq or lontara' to denote the glotal stop at the end) also refers to a literary genre that deals with history and genealogies, the most widely written and important writing topics by the Buginese and Makassarese people. This genre can be divided into several sub-types: genealogy (lontara' pangngoriseng), daily notes (lontara' bilang), and historical or chronical records (patturioloang). Each kingdom of South Sulawesi generally has its own historical records which are compiled from the three types of genres mentioned above in certain compositional conventions.[17] Compared to "historical" records from other parts of the archipelago, the historical record in the literary tradition of South Sulawesi is considered to be one of the most "realistic"; historical events are explained in a straightforward and plausible manner, and relatively few fantastic elements appear or are accompanied by markers such as the word "supposedly" so that the overall record feels factual and realistic.[18][19] Even so, historical records such as the Makassar's patturiolong are inseparable from their political function as a means of ratifying power, descent, and territorial claims of certain rulers.[20] One of these patturiolongs that was written in Makasar script and have been researched by experts is the Chronicle of Gowa which describes the history of the kings of Gowa from the founding of the Kingdom of Gowa to the reign of Sultan Hasanuddin in the 17th century AD.

The use of diaries is one of the unique literary phenomena of South Sulawesi that did not seem to happen in other Indonesian written traditions. The diary writers are generally people of high rank, such as the sultans, the rulers(arung), or the prime ministers (tumailalang). This kind of diary generally has a table that has been divided into rows and dates, and on these rows the author puts a record of events that he deems important on that date. Often many lines are left blank, but if a day has lots of notes, then often the letters are twisted and turned to occupy all the remaining empty space on the page so that one date only use one continuous line.

Ambiguity

Makasar script does not have a virama or other ways to write dead syllables even though Makassarese language has many words with dead syllables. The word baba 𑻤𑻤 in the Makassar script can refer to six possible words: baba, baba', ba'ba, ba'ba', bamba, and bambang. Given that Makassar script writing are also written continually without any consistent sentence break marking, Manuscripts often have a lot of ambiguous words which can often only be distinguished through context. Readers of the Makasar text need an adequate initial understanding of the language and contents of the text in question in order to be able to read the text fluently. This ambiguity is analogous to the use of bald Arabic letters; readers whose native language uses Arabic characters intuitively understand which vowels are appropriate to use in the context of the sentence concerned, so that vowel markers are not needed in standard everyday texts.

Even so, sometimes even context isn't sufficient to reveal how to read a sentence whose reference is unknown to the reader. As an illustration, Cummings and Jukes provide the following example to illustrate how Makassar script can produce different meanings depending on how the reader cuts and fills in the ambiguous part:

| Makasar script | Possible reading | |

|---|---|---|

| Latin | Meaning | |

| 𑻱𑻤𑻵𑻦𑻱𑻳[21] | a'bétai | he won (intransitive) |

| ambétai | he beat... (transitive) | |

| 𑻨𑻠𑻭𑻵𑻱𑻳𑻣𑻵𑻣𑻵𑻤𑻮𑻧𑻦𑻶𑻠[22] | nakanréi pépé' balla' datoka | fire devouring a temple |

| nakanréi pépé' balanda tokka' | fire devouring a bald Hollander | |

Without knowing the intent or event to which the author may be referring, it is impossible for a general reader to determine the "correct" reading of the above sentence by himself. Even the most proficient reader often needs to pause to interpret what they are reading.[23]

Form

Basic letters

Basic letters (𑻱𑻭𑻶𑻮𑻶𑻦𑻭 anrong lontara’ ) in Makasar script represents a syllable with inherent /a/. There are 18 basic letters, shown below:[2]

| ka | ga | nga | pa | ba | ma | ta | da | na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 𑻠 | 𑻡 | 𑻢 | 𑻣 | 𑻤 | 𑻥 | 𑻦 | 𑻧 | 𑻨 |

| ca | ja | nya | ya | ra | la | wa | sa | a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 𑻩 | 𑻪 | 𑻫 | 𑻬 | 𑻭 | 𑻮 | 𑻯 | 𑻰 | 𑻱 |

Note that the Makassar script has never undergone a standardization process like the Buginese Lontara script later on, so there are many variations of writing that can be found in Makassar manuscripts. [24] The form in the table above is adapted from the characters used in the diary of Pangeran Gowa, Tropenmuseum collection, numbered KIT 668-216.

Diacritic

Diacritics (𑻱𑻨𑻮𑻶𑻦𑻭 ana’ lontara’) are markings on the basic letters to change its vowel. There are 4 diacritics, shown below:[2]

| -i | -u | -e[1] | -o | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| ||

| Name | ana' i rate | ana' i rawa | ana' ri olo | ana' ri boko | |

| na | ni | nu | ne | no | |

|

|

|

|

| |

| 𑻨 | 𑻨𑻳 | 𑻨𑻴 | 𑻨𑻵 | 𑻨𑻶 | |

Notes

| |||||

Punctuation

Historical texts of Makassar is written without spaces between words (scriptio continua) and does not use punctuations. The Makassar script is known to have only two original punctuation marks: passimbang and a section ending mark. Passimbang functions like a period or comma in Latin letters by dividing text into chunks that are similar (but not the same) as stanzas or sentences, while section ending marks are used to split text into chapter-like units. [2]

| passimbang | section end |

|---|---|

|

|

| 𑻷 | 𑻸 |

In certain manuscripts, the ending mark of a section is replaced by a punctuation that resembles a palm tree (🌴), and for the end of larger sections it is common to use the stylization of the word tammat which uses Arabic letters تمت).[2]

Repeated consonants

Continuous syllables with the same initial consonant are often written in abbreviated form using double diacritics or a repeater letter angka which can then be reattached with a diacritic. Its use can be seen as follows: [2]

|

|

Example texts

The following is an excerpt from the Chronicle of Gowa which tells the course of a battle between the Gowa and the Kingdom of Tallo which culminated in their alliance during the reign of Karaeng Gowa Tumapa'risi 'Kallonna and Karaeng Tallo Tunipasuru'. [a][14]

𑻱𑻳𑻬𑻦𑻶𑻥𑻳𑻱𑻨𑻵𑻷𑻥𑻡𑻱𑻴𑻷𑻨𑻨𑻳𑻮𑻳𑻣𑻴𑻢𑻳𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻤𑻴𑻧𑻴𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻦𑻴𑻦𑻮𑻶𑻠𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻦𑻴𑻥𑻭𑻴𑻰𑻴𑻠𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻦𑻴𑻣𑻶𑻮𑻶𑻤𑻠𑻵𑻢𑻷 ia–tommi anne. ma'gau'. na nilipungi. nibundu'. ri tu Talloka. ri tu Marusuka. ri tu Polombangkenga. On the reign [of Tumapa'risi' Kallonna] he too was surrounded and attacked by the Tallo, the Maros, [and] the Polombangkeng people. 𑻠𑻭𑻱𑻵𑻢𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻦𑻮𑻶𑻷𑻨𑻱𑻡𑻱𑻢𑻷𑻰𑻳𑻯𑻵𑻷𑻦𑻴𑻨𑻳𑻣𑻱𑻰𑻴𑻭𑻴𑻷 Karaenga. ri Tallo'. naagaanga. siewa. Tunipasuru'. The Karaeng Tallo that fought him was Tunipasuru'. 𑻱𑻭𑻵𑻠𑻮𑻵𑻨𑻷𑻱𑻳𑻬𑻠𑻴𑻥𑻤𑻰𑻴𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻠𑻨𑻷𑻱𑻳𑻥𑻢𑻬𑻶𑻯𑻤𑻵𑻭𑻷 areng kalenna. iang kumabassung. nikana. I Mangayoaberang. His given name, may i not be damned [for insolently calling his name], was I Mangayoaberang. 𑻥𑻡𑻯𑻴𑻠𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻥𑻭𑻴𑻰𑻴𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻠𑻨𑻷𑻣𑻦𑻨𑻮𑻠𑻨 ma'gauka. ri Marusu'. nikana. Patanna Langkana. [Meanwhile, the ruler] that ruled in Maros [on that time] was Patanna Langkana. 𑻱𑻭𑻵𑻥𑻦𑻵𑻨𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻠𑻨𑻷𑻦𑻴𑻥𑻥𑻵𑻨𑻭𑻳𑻤𑻴𑻮𑻴𑻧𑻴𑻯𑻬𑻷 areng matena. nikana. Tumamenang ri Bulu'duaya. His posthumous name is Tumamenang ri Bulu'duaya. 𑻱𑻭𑻵𑻠𑻮𑻵𑻨𑻱𑻳𑻬𑻠𑻴𑻥𑻤𑻰𑻴𑻷𑻱𑻳𑻥𑻣𑻰𑻶𑻤𑻷 areng kalenna iang kumabassung. I Mappasomba. His given name, may i not be damned, was I Mappasomba. 𑻱𑻭𑻵𑻣𑻥𑻨𑻨𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻠𑻨𑻷𑻱𑻳𑻧𑻱𑻵𑻢𑻴𑻭𑻡𑻷 areng pamana'na. nikana. I Daeng Nguraga. His proper name was I Daeng Nguraga. 𑻦𑻴𑻥𑻡𑻱𑻴𑻠𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻤𑻪𑻵𑻷𑻱𑻨𑻨𑻷𑻠𑻭𑻱𑻵𑻮𑻶𑻯𑻵𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻠𑻨𑻬𑻧𑻱𑻵𑻨𑻱𑻳𑻣𑻰𑻱𑻳𑻭𑻳𑻷𑻠𑻠𑻨𑻱𑻳𑻧𑻱𑻵𑻥𑻰𑻭𑻶𑻷 Tuma'gauka. ri Bajeng. ana'na. Karaeng Loe. nikanaya Daenna I Pasairi. kakanna I Daeng Masarro. He who ruled in Bajeng [Polombangkeng] is the son of Karaeng Loe, named Daenna I Pasairi, older sibbling of I Daeng Masarro. 𑻱𑻳𑻬𑻥𑻳𑻨𑻵𑻷𑻰𑻭𑻳𑻤𑻱𑻦𑻷𑻦𑻴𑻥𑻡𑻱𑻴𑻠𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻰𑻭𑻤𑻶𑻨𑻵𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻮𑻵𑻠𑻵𑻰𑻵𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻠𑻦𑻳𑻢𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻪𑻥𑻭𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻪𑻳𑻣𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻥𑻧𑻮𑻵𑻷 iaminne. sari'battang. Tuma'gauka. ri Sanrabone. ri Lengkese'. ri Katingang. ri Jamarang. ri Jipang. ri Mandalle'. This [I Pasairi] were sibblings with those that ruled in Sanrabone, in Lengkese', in Katingang, in Jamarang, in Jipang, [and] in Mandalle'.[b] 𑻦𑻴𑻪𑻴𑻱𑻳𑻰𑻳𑻰𑻭𑻳𑻤𑻦𑻷𑻥𑻮𑻮𑻰𑻳𑻣𑻴𑻯𑻵𑻢𑻱𑻰𑻵𑻷𑻷 tujui sisari'battang. ma'la'lang sipue–ngaseng. seven sibblings, all half-umbrella'd [=ruled].[c] 𑻱𑻳𑻬𑻥𑻳𑻨𑻵𑻠𑻭𑻱𑻵𑻷𑻨𑻳𑻮𑻳𑻣𑻴𑻢𑻳𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻡𑻱𑻴𑻠𑻦𑻮𑻴𑻯𑻷 iaminne Karaeng. nilipungi. ri Gaukang Tallua. This Karaeng [Tumapa'risi' Kallonna] is supported by The Three Gaukang.[d] 𑻠𑻭𑻱𑻵𑻢𑻭𑻳𑻮𑻠𑻳𑻬𑻴𑻷𑻱𑻢𑻡𑻢𑻳𑻷𑻡𑻴𑻭𑻴𑻧𑻬𑻷𑻦𑻴𑻥𑻢𑻰𑻬𑻷𑻦𑻴𑻦𑻶𑻤𑻶𑻮𑻶𑻠𑻷𑻦𑻴𑻰𑻱𑻶𑻥𑻦𑻬𑻷 Karaenga ri Lakiung. angngagangi. Gurudaya. tu Mangngasaya. tu Tomboloka. tu Saomataya. Kareng Lakiung accompanies Gurudaya, [along with] Mangngasa, Tombolo' and Saomata people, 𑻱𑻪𑻶𑻭𑻵𑻢𑻳𑻷𑻠𑻮𑻵𑻨𑻷𑻱𑻳𑻥𑻥𑻠𑻰𑻳𑻷𑻤𑻭𑻶𑻤𑻶𑻰𑻶𑻷𑻨𑻣𑻥𑻵𑻦𑻵𑻢𑻳𑻷 anjorengi. kalenna. imamakasi. Baro'boso'. napammenténgi. there they set camp, in Baro'boso', on alert, 𑻱𑻳𑻬𑻥𑻳𑻨𑻱𑻡𑻱𑻷𑻰𑻳𑻦𑻴𑻪𑻴𑻷𑻦𑻶𑻣𑻶𑻮𑻶𑻤𑻱𑻠𑻵𑻢𑻷 iami naagaang. situju. tu Polombangkenga. they joined together [to] face Polombangkeng people.

Comparison to Lontara script

In its development, the use of Makassar script was gradually replaced by Lontara Bugis script which by Makassar writers is sometimes referred to as "new lontara". These two closely related scripts have almost identical writing rules, although in appearance they look quite different. A comparison of the two characters can be seen as follows:[25]

| ka | ga | nga | ngka | pa | ba | ma | mpa | ta | da | na | nra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makasar | ||||||||||||

| 𑻠 | 𑻡 | 𑻢 | 𑻣 | 𑻤 | 𑻥 | 𑻦 | 𑻧 | 𑻨 | ||||

| Bugis | ||||||||||||

| ᨀ | ᨁ | ᨂ | ᨃ | ᨄ | ᨅ | ᨆ | ᨇ | ᨈ | ᨉ | ᨊ | ᨋ | |

| ca | ja | nya | nca | ya | ra | la | wa | sa | a | ha | ||

| Makasar | ||||||||||||

| 𑻩 | 𑻪 | 𑻫 | 𑻬 | 𑻭 | 𑻮 | 𑻯 | 𑻰 | 𑻱 | ||||

| Bugis | ||||||||||||

| ᨌ | ᨍ | ᨎ | ᨏ | ᨐ | ᨑ | ᨒ | ᨓ | ᨔ | ᨕ | ᨖ |

| -a | -i | -u | -é[1] | -o | -e[2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | ni | nu | né | no | ne | |

| Makasar | ||||||

| 𑻨 | 𑻨𑻳 | 𑻨𑻴 | 𑻨𑻵 | 𑻨𑻶 | ||

| Bugis | ||||||

| ᨊ | ᨊᨗ | ᨊᨘ | ᨊᨙ | ᨊᨚ | ᨊᨛ | |

| Notes | ||||||

| Makasar | passimbang | section end |

|---|---|---|

| 𑻷 | 𑻸 | |

| Bugis | pallawa | section end |

| ᨞ | ᨟ |

Unicode

Makasar script has been added to the Unicode Standard in June 2018 on Version 11.0.[26]

The Unicode block for the Makassar script is U+11EE0–U+11EFF and contains 25 characters:

| Makasar[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+11EEx | 𑻠 | 𑻡 | 𑻢 | 𑻣 | 𑻤 | 𑻥 | 𑻦 | 𑻧 | 𑻨 | 𑻩 | 𑻪 | 𑻫 | 𑻬 | 𑻭 | 𑻮 | 𑻯 |

| U+11EFx | 𑻰 | 𑻱 | 𑻲 | 𑻳 | 𑻴 | 𑻵 | 𑻶 | 𑻷 | 𑻸 | |||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Font

A font for Makasar script based on the unicode block were first created under the name Jangang-jangang in early 2020.[27] This font support the graphite SIL technology and double letters, both with angka (example: 𑻥𑻲𑻳 mami) and by double diacritic (example: 𑻥𑻳𑻳 mimi and 𑻥𑻴𑻴 mumu).

Notes

- ^ The spelling of the original Makasar script is preserved here, while the color of the writing has been turned uniformly black. Transliteration and translation adapted from Jukes (2019), with some additional information from the translated version of William Cummings (2007).

- ^ The kingdums mentioned in this line, along with the Bajeng mentioned earlier, are the seven countries that make up the Polombangkeng confederation.[13]

- ^ La'lang sipue or "half umbrella" is a kind of umbrella made of palm leaves which is used at the inauguration of a ruler.[14]

- ^ "The Three Gaukang" refers to Gowa's banners of greatness called Gurudaya, Sulengkaya, and Cakkuridia.[14]

References

- ^ a b Jukes 2019, pp. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f Pandey, Anshuman (2015-11-02). "Proposal for encoding the Makassar script in Unicode" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 (L2/15-233). Unicode.

- ^ Macknight 2016, p. 55.

- ^ Macknight 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Tol 1996, p. 214.

- ^ Jukes 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Noorduyn 1993, pp. 567–568.

- ^ Miller, Christopher (2010). "A Gujarati origin for scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines". Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 36 (1).

- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Jukes 2019, pp. 46.

- ^ Jukes 2019, pp. 47.

- ^ Ahmad M. Sewang (2005). Islamisasi Kerajaan Gowa: abad XVI sampai abad XVII. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 37-38. ISBN 9789794615300.

- ^ a b Cummings, William P. (2002). Making Blood White: Historical Transformations in Early Modern Makassar. 2840 Kolowalu St, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824825133.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c d Cummings, William P. (2007). A Chain of Kings: The Makassarese Chronicles of Gowa and Talloq. KITLV Press. ISBN 978-9067182874.

- ^ Jukes 2014, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Jukes 2019, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Tol 1996, pp. 223–226.

- ^ Cummings 2007, p. 8. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCummings2007 (help)

- ^ Macknight, Charles Campbell; Paeni, Mukhlis; Hadrawi, Muhlis, eds. (2020). The Bugis Chronicle of Bone. Translated by Campbell Macknight; Mukhlis Paeni; Muhlis Hadrawi. Canberra: Australian National University Press. p. xi-xii. ISBN 9781760463588.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Cummings 2007, p. 11. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCummings2007 (help)

- ^ Jukes 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Cummings, William (2002). Making Blood White: historical transformations in early modern Makassar. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824825133.

- ^ Jukes 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Jukes 2014, pp. 1.

- ^ Jukes 2014, pp. 2, Tabel 1.

- ^ "Unicode 11.0.0". Unicode Consortium. 2018-06-05. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ^ "Aksara di Nusantara %7C Download Font Aksara Jangang-Jangang". Aksara di Nusantara. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

Bibliography

- Cense, A (1966). "Old Buginese and Macassarese diaries" (PDF). Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 122 (4). Leiden: 416-428.

- Cummings, William P. (January 1, 2007). A Chain of Kings: The Makassarese Chronicles of Gowa and Talloq. KITLV Press. ISBN 978-9067182874.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Jukes, Anthony (2019-12-02). A Grammar of Makasar: A Language of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-41266-8.

- Jukes, Anthony (2014). "Writing and Reading Makassarese". International Workshop of Endangered Scripts of Island Southeast Asia: Proceedings. LingDy2 Project, Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Noorduyn, Jacobus (1993). "Variation in the Bugis/Makasarese script". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 149 (3). KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies: 533–570.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pandey, Anshuman (2015-11-02). "Proposal for encoding the Makassar script in Unicode" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 (L2/15-233). Unicode.

- Tol, Roger (1996). "A Separate Empire: Writings of South Sulawesi". In Ann Kumar; John H. McGlynn (eds.). Illuminations: The Writing Traditions of Indonesia. Jakarta: Lontar Foundation. ISBN 0834803496.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

See also

External links

Digital books

- A collection of documents in Makasar language and script between the 18th and 19th centuries AD, British Library collection no. Add MS 12351

Others

- Unicode Proposal on Makasar Script

- Preliminary Unicode Proposal on Makasar Script

- Download Makasar script font on Aksara di Nusantara or here