Croconic acid

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

4,5-Dihydroxycyclopent-4-ene-1,2,3-trione | |||

| Other names

Crocic acid

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.201.686 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C5H2O5 | |||

| Molar mass | 142.07 | ||

| Melting point | > 300 °C (572 °F; 573 K) (decomposes) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 0.80, 2.24 | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

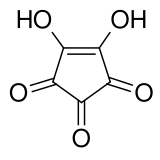

Croconic acid or 4,5-dihydroxycyclopentenetrione is a chemical compound with formula C5H2O5 or (C=O)3(COH)2. It has a cyclopentene backbone with two hydroxyl groups adjacent to the double bond and three ketone groups on the remaining carbon atoms. It is sensitive to light,[1] soluble in water and ethanol[2] and forms yellow crystals that decompose at 212 °C.[3]

The compound is acidic and loses the protons from the hydroxyl groups (pKa1 = 0.80±0.08 and pKa2 = 2.24±0.01 at 25 °C).[4][5] The resulting anions, hydrogencroconate C5HO−5[1] and croconate C5O2−5 are also quite stable. The croconate ion, in particular, is aromatic[6] and symmetric, as the double bond and the negative charges become delocalized over the five CO units (with two electrons, Hückel's rule means this is an aromatic configuration). The lithium, sodium and potassium croconates crystallize from water as dihydrates[7] but the orange potassium salt can be dehydrated to form a monohydrate.[1][4] The croconates of ammonium, rubidium and caesium crystallize in the anhydrous form.[7] Salts of barium, lead, silver, and others[specify] are also known.[1]

Croconic acid also forms ethers such as dimethyl croconate where the hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group is substituted with an alkyl group.

History

Croconic acid and potassium croconate dihydrate were discovered by Leopold Gmelin in 1825, who named the compounds from Greek κρόκος meaning "crocus" or "egg yolk".[7] The structure of ammonium croconate was determined by Baenziger et al. in 1964. The structure of K2C5O5·2H2O was determined by Dunitz in 2001.[8]

Structure

In the solid state, croconic acid has a peculiar structure consisting of pleated strips, each "page" of the strip being a planar ring of 4 molecules of C5O5H2 held together by hydrogen bonds.[7] In dioxane it has a large dipole moment of 9–10 D, while the free molecule is estimated to have a dipole of 7–7.5 D.[9] The solid is ferroelectric with a Curie point above 400 K (127 °C), indeed the organic crystal with the highest spontaneous polarization (about 20 μC/cm2). This is due to proton transfer between adjacent molecules in each pleated sheet, rather than molecular rotation.[9]

In the solid alkali metal salts, the croconate anions and the alkali cations form parallel columns.[7] In the mixed salt K3(HC5O5)(C5O5)·2H2O, which formally contains both one croconate dianion C5O2−5 and one hydrogencroconate monoanion (HC5O−5), the hydrogen is shared equally by two adjacent croconate units.[7]

Salts of the croconate anion and its derivatives are of interest in supramolecular chemistry research because of their potential for π-stacking effects, where the delocalized electrons of two stacked croconate anions interact.[10]

Infrared and Raman assignments indicate that the equalization of the carbon–carbon bond lengths, thus the electronic delocalization, follows with an increase in counter-ion size for salts.[6] This result leads to a further interpretation that the degree of aromaticity is enhanced for salts as a function of the size of the counter-ion. The same study provided quantum mechanical DFT calculations for the optimized structures and vibrational spectra which were in agreement with experimental findings. The values for calculated theoretical indices of aromaticity also increased with counterion size.

The croconate anion forms hydrated crystalline coordination compounds with divalent cations of transition metals, with general formula M(C5O5)·3H2O; where M stands for copper (yielding a brown solid), iron (dark purple), zinc (yellow), nickel (green), manganese (dark green), or cobalt (purple). These complexes all have the same orthorombic crystal structure, consisting of chains of alternating croconate and metal ions. Each croconate is bound to the preceding metal by one oxygen atom, and to the next metal through its two opposite oxygens, leaving two oxygens unbound. Each metal is bound to three croconate oxygens and to one water molecule.[11] Calcium also forms a compound with the same formula (yellow) but the structure appears to be different.[11]

The croconate anion also forms compounds with trivalent cations such as aluminium (yellow), chromium (brown), and iron (purple). These compounds also include hydroxyl groups as well as hydration water and have a more complicated crystal structure.[11] No indication was found of sandwich-type bonds between the delocalized electrons and the metal (as are seen in ferrocene, for example),[11] but the anion can form metal complexes with a large variety of bonding patterns, involving from only one to all five of its oxygen atoms.[12][13][14]

See also

- Croconate violet

- Croconate blue

- Rhodizonic acid

- Squaric acid

- Deltic acid

- Cyclopentanepentone (leuconic acid)

References

- ^ a b c d Yamada, K.; Mizuno, N.; Hirata, Y. (1958). "Structure of croconic acid". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 31 (5): 543–549. doi:10.1246/bcsj.31.543.

- ^ Miller, W. A. (1868). Elements of Chemistry: Theoretical and Practical (4th ed.). Longmans.[page needed]

- ^ Turner, E. Elements of Chemistry.[page needed]

- ^ a b Schwartz, L. M.; Gelb, R. I.; Yardley, J. O. (1975). "Aqueous dissociation of croconic Acid". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 79 (21): 2246–2251. doi:10.1021/j100588a009.

- ^ Gelb, R. I.; Schwartz, L. M.; Laufer, D. A.; Yardley, J. O. (1977). "The structure of aqueous croconic acid". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 81 (13): 1268–1274. doi:10.1021/j100528a010.

- ^ a b Georgopoulos, S. L.; Diniz, R.; Yoshida, M. I.; Speziali, N. L.; Dos Santos, H. F.; Junqueira, G. M. A.; de Oliveira, L. F. C. (2006). "Vibrational spectroscopy and aromaticity investigation of squarate salts: A theoretical and experimental approach". Journal of Molecular Structure. 794 (1–3): 63–70. Bibcode:2006JMoSt.794...63G. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2006.01.035.

- ^ a b c d e f Braga, D.; Maini, L.; Grepioni, F. (2002). "Croconic acid and alkali metal croconate salts: Some new insights into an old story". Chemistry – A European Journal. 8 (8): 1804–1812. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20020415)8:8<1804::AID-CHEM1804>3.0.CO;2-C.

- ^ Dunitz, J. D.; Seiler, P.; Czechtizky, W. (2001). "Crystal structure of potassium croconate dihydrate, after 175 years". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (9): 1779–1780. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010504)40:9<1779::AID-ANIE17790>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 11353510.

- ^ a b Horiuchi, S.; Tokunaga, Y.; Giovannetti, G.; Picozzi, S.; Itoh, H.; Shimano, R.; Kumai, R.; Tokura, Y. (2010). "Above-room-temperature ferroelectricity in a single-component molecular crystal". Nature. 463 (7282): 789–92. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..789H. doi:10.1038/nature08731. PMID 20148035. S2CID 205219520.

- ^ Faria, L. F. O.; Soares, A. L., Jr.; Diniz, R.; Yoshida, M. I.; Edwards, H. G. M.; de Oliveira, L. F. C. (2010). "Mixed salts containing croconate violet, lanthanide and potassium ions: Crystal structures and spectroscopic characterization of supramolecular compounds". Inorganica Chimica Acta. 363 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2009.09.050.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d West, R.; Niu, H. Y. (1963). "New aromatic anions. VI. Complexes of croconate ion with some divalent and trivalent metals (Complexes of divalent transition metal croconates and trivalent metal croconates)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 85 (17): 2586. doi:10.1021/ja00900a013.

- ^ Carranza, J.; Sletten, J.; Lloret, F.; Julve, M. (2009). "Manganese(II) complexes with croconate and 2-(2-pyridyl)imidazole ligands: Syntheses, X-ray structures and magnetic properties". Inorganica Chimica Acta. 362 (8): 2636–2642. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2008.12.002.

- ^ Wang, C.-C.; Ke, M.-J.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, I.-H.; Lin, S.-I.; Lin, T.-Y.; Wu, L.-M.; Lee, G.-H.; Sheu, H.-S.; Fedorov, V. E. (2009). "[M(C5O5)2(H2O)n]2− as a building block for hetero- and homo-bimetallic coordination polymers: From 1D chains to 3D supramolecular architectures". Crystal Growth & Design. 9 (2): 1013–1019. doi:10.1021/cg800827a.

{{cite journal}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|title=at position 1 (help) - ^ M., S. C.; Ghosh, A. K.; Zangrando, E.; Chaudhuri, N. R. (2007). "3D supramolecular networks of Co(II)/Fe(II) using the croconate dianion and a bipyridyl spacer: Synthesis, crystal structure and thermal study". Polyhedron. 26 (5): 1105–1112. doi:10.1016/j.poly.2006.09.100.

External links

Media related to Croconic acid at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Croconic acid at Wikimedia Commons