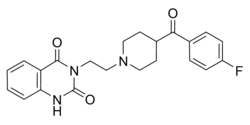

Ketanserin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sufrexal |

| Other names | R41468; R-41468; R-41,468 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.070.598 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H22FN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 395.434 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Ketanserin (INN, USAN, BAN) (brand name Sufrexal; former developmental code name R41468) is a drug used clinically as an antihypertensive agent and in scientific research to study the serotonin system; specifically, the 5-HT2 receptor family.[1] It was discovered at Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1980.[2][3]

Medical use

Ketanserin is classified as an antihypertensive by the World Health Organization[4] and the National Institute of Health.[5]

It has been used to reverse pulmonary hypertension caused by protamine (which in turn was administered to reverse the effects of heparin overdose).[6]

The reduction in hypertension is not associated with reflex tachycardia.[7]

It has been used in cardiac surgery.[8]

A 2000 Cochrane Review found that, compared to placebo, ketanserin did not provide significant relief for people suffering from Raynaud's phenomenon attacks in the setting of progressive systemic sclerosis (an autoimmune disorder). While the frequency of the attacks was unaffected by ketanserin, there was a reduction in the duration of the individual attacks. However, due to the significant adverse effect burden, the authors concluded that ketanserin's utility for this indication is likely unbeneficial.[9]

Research use

With tritium (3H) radioactively labeled ketanserin is used as a radioligand for serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, e.g. in receptor binding assays and autoradiography.[10] This radio-labeling has enabled the study of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor distribution in the human brain.[11]

An autoradiography study of the human cerebellum has found an increasing binding of 3H-ketanserin with age (from below 50 femtomol per milligram tissue at around 30 years of age to over 100 above 75 years).[12] The same research team found no significant correlation with age in their homogenate binding study.

Ketanserin has also been used with carbon (11C) radioactively labeled NNC112 in order to image cortical D1 receptors without contamination by 5-HT2 receptors.[13]

Increasing research into the use of psychedelics as antidepressants has seen ketanserin used to both terminate the hallucinogenic experience, and to disentangle the specific cognitive effects of 5-HT2A activation.[14]

Pharmacology

Ketanserin is a high-affinity non-selective antagonist of 5-HT2 receptors in rodents,[15][16] with Ki values of 2–3 nM for the 5-HT2A receptor and 28 nM for the 5-HT2C receptor).[15][17] In primates including humans however, ketanserin is a more selective antagonist of the 5-HT2A over the 5-HT2C receptor,[15] with Ki values of 2–3 nM for the 5-HT2Areceptor and 130 nM for the 5-HT2C receptor.[15] In addition to the 5-HT2 receptors, ketanserin is also a high affinity antagonist for the H1 receptor (Ki = 2 nM),[15][18] and has measurable albeit relatively low affinity for a number of other receptors:

- α1-adrenergic receptors (Ki = ~40 nM)[18]

- α2-adrenergic receptors = ~200 nM) [citation needed]

- 5-HT1D receptors (Ki = ? nM) [17][19]

- 5-HT2B receptors (Ki = ? nM)[20]

- 5-HT6 receptors (Ki = ~300 nM)[21]

- 5-HT7 receptors (Ki = ? nM)[17]

- D1 receptors (~300 nM)[18]

- D2 receptors (Ki = ~500 nM) receptors.[15][18]

It has also been found to block the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2).[22][23]

See also

References

- ^ Gopi Doctor Ahuja (2005). Drug Injury: Liability, Analysis, and Prevention. Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company. pp. 304–. ISBN 978-0-913875-27-8.

- ^ David Healy (1 July 2009). The Creation of Psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-0-674-03845-5.

- ^ Harry Schwartz (August 1989). Breakthrough: the discovery of modern medicines at Janssen. Skyline Pub. Group. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-56019-100-1.

- ^ ATC/DDD Index

- ^ Ketanserin

- ^ van der Starre PJ, Solinas C (1996). "Ketanserin in the treatment of protamine-induced pulmonary hypertension". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 23 (4): 301–4. PMC 325377. PMID 8969033.

- ^ Hodsman NB, Colvin JR, Kenny GN (May 1989). "Effect of ketanserin on sodium nitroprusside requirements, arterial pressure control and heart rate following coronary artery bypass surgery". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 62 (5): 527–31. doi:10.1093/bja/62.5.527. PMID 2786422.

- ^ Elbers PW, Ozdemir A, van Iterson M, van Dongen EP, Ince C (December 2008). "Microcirculatory Imaging in Cardiac Anesthesia: Ketanserin Reduces Blood Pressure But Not Perfused Capillary Density". J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 23 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2008.09.013. PMID 19058975.

- ^ Pope, J; Fenlon, D; Thompson, A; Shea, B; Furst, D; Wells, G; Silman, A (2000). "Ketanserin for Raynaud's phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000954. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000954. PMC 7032891. PMID 10796396.

- ^ Eickhoff SB, Schleicher A, Scheperjans F, Palomero-Gallagher N, Zilles K (2007). "Analysis of neurotransmitter receptor distribution patterns in the cerebral cortex". NeuroImage. 34 (4): 1317–30. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.016. PMID 17182260.

- ^ Pazos A, Probst A, Palacios JM (1987). "Serotonin receptors in the human brain--IV. Autoradiographic mapping of serotonin-2 receptors". Neuroscience. 21 (1): 123–39. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(87)90327-7. PMID 3601071.

- ^ Eastwood SL, Burnet PW, Gittins R, Baker K, Harrison PJ (2001). "Expression of serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptors in the human cerebellum and alterations in schizophrenia". Synapse. 42 (2): 104–14. doi:10.1002/syn.1106. PMID 11574947.

- ^ Catafau AM, Searle GE, Bullich S, Gunn RN, Rabiner EA, Herance R, Radua J, Farre M, Laruelle M (2010). "Imaging cortical dopamine D1 receptors using 11C NNC112 and ketanserin blockade of the 5-HT 2A receptors". J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 30 (5): 985–93. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2009.269. PMC 2949183. PMID 20029452.

- ^ Quednow, Boris B.; Kometer, Michael; Geyer, Mark A.; Vollenweider, Franz X. (February 2012). "Psilocybin-Induced Deficits in Automatic and Controlled Inhibition are Attenuated by Ketanserin in Healthy Human Volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology. 37 (3): 630–640. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.228. ISSN 1740-634X. PMC 3260978.

- ^ a b c d e f NIMH Psychoactive Drug Screening Program

- ^ Creed-Carson M; Oraha A. Norbrega JN. (2011). "Effects of 5-HT(2A) and 5-HT(2C) receptor antagonists on acute and chronic dyskinetic effects induced by haloperidol in rats". Behav Brain Res. 219 (2): 273–279. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.025. PMID 21262266.

- ^ a b c Alfredo Meneses (11 March 2014). The Role of 5-HT Systems on Memory and Dysfunctional Memory: Emergent Targets for Memory Formation and Memory Alterations. Elsevier Science. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-12-801083-9.

- ^ a b c d C.P. Coyne (9 January 2008). Comparative Diagnostic Pharmacology: Clinical and Research Applications in Living-System Models. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-0-470-34429-3.

- ^ B. Olivier; I. van Wijngaarden; W. Soudijn (10 July 1997). Serotonin Receptors and their Ligands. Elsevier. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-0-08-054111-2.

- ^ Mark Chapman (2007). Evaluation of the Role of Serotonin in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Broilers Induced by Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide and Cellulose Microparticles. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-549-36052-0.

- ^ Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 388–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ^ Christian P. Muller; Barry Jacobs (30 December 2009). Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin. Academic Press. pp. 592–. ISBN 978-0-08-087817-1.

- ^ Catecholamines: Bridging Basic Science with Clinical Medicine: Bridging Basic Science with Clinical Medicine. Academic Press. 20 October 1997. pp. 237–. ISBN 978-0-08-058134-7.