Sidney Reilly

Sidney Reilly | |

|---|---|

Reilly's 1918 German passport (issued to "George Bergmann") | |

| Born | c. 1873[a] Possibly Odessa, Russian Empire |

| Died | 5 November 1925 (aged 51) |

| Other names | "Ace of Spies" |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service branch | |

| Codename | S.T.I.[8] |

| Operations | Lockhart Plot[4] D'Arcy Concession[5] Zinoviev Letter[6][7] |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1917–1921 |

| Rank | Second Lieutenant |

| Awards | Military Cross |

Sidney George Reilly MC (/ˈraɪli/; c. 1873[a] – 5 November 1925)—known as "Ace of Spies"—was a Russian-born adventurer and secret agent employed by Scotland Yard's Special Branch and later by the Foreign Section of the British Secret Service Bureau,[9] the precursor to the modern British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6/SIS).[10][11] He is alleged to have spied for at least four different great powers,[1] and documentary evidence indicates that he was involved in espionage activities in 1890s London among Russian émigré circles, in Manchuria on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), and in an abortive 1918 coup d'état against Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik government in Moscow.[12]

Reilly disappeared in Soviet Russia in the mid-1920s, lured by Cheka's Operation Trust. British diplomat and journalist R. H. Bruce Lockhart publicised his and Reilly's 1918 exploits to overthrow the Bolshevik regime[13] in Lockhart's 1932 book Memoirs of a British Agent.[14] This became an international best-seller and garnered global fame for Reilly. The memoirs retold the efforts by Reilly, Lockhart, and other conspirators to sabotage the Bolshevik revolution while still in its infancy.

The world press made Reilly into a household name within five years of his execution by Soviet agents in 1925, lauding him as a peerless spy and recounting his many espionage adventures. Newspapers dubbed him "the greatest spy in history" and "the Scarlet Pimpernel of Red Russia".[15] The London Evening Standard described his exploits in an illustrated serial in May 1931 headlined "Master Spy". Ian Fleming used him as a model for James Bond in his novels (set in the early Cold War).[16] Reilly is considered to be "the dominating figure in the mythology of modern British espionage".[17]

Birth and youth

The true details about Reilly's origin, identity, and exploits have eluded researchers and intelligence agencies for more than a century. Reilly himself told several versions of his background to confuse and mislead investigators.[18] At different times in his life, he claimed to be the son of an Irish merchant seaman,[19] an Irish clergyman, and an aristocratic landowner connected to the court of Emperor Alexander III of Russia. According to a Soviet secret police dossier compiled in 1925,[20] he was perhaps born Zigmund Markovich Rozenblum on 24 March 1874 in Odessa,[a][20] a Black Sea port of Emperor Alexander II's Russian Empire. His father Markus was a doctor and shipping agent, according to this dossier, while his mother came from an impoverished noble family.[20][24]

Other sources claim that Reilly was born Georgy Rosenblum in Odessa on 24 March 1873.[25] In one account,[26] his birth name is given as Salomon Rosenblum in Kherson Gubernia of the Russian Empire,[26] the illegitimate son of Polina (or "Perla") and Dr. Mikhail Abramovich Rosenblum, the cousin of Reilly's father Grigory Rosenblum.[26] There is also speculation that he was the son of a merchant marine captain and Polina.

Yet another source states that he was born Sigmund Georgievich Rosenblum on 24 March 1874,[17] the only son of Pauline and Gregory Rosenblum,[27] a wealthy Polish-Jewish family with an estate at Bielsk in the Grodno Province of Imperial Russia. His father was known locally as George rather than Gregory, hence Sigmund's patronymic Georgievich.[27] The family seems to have been well-connected in Polish nationalist circles through Pauline's intimate friendship with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the Polish statesman who became Prime Minister of Poland and also Poland's foreign minister in 1919.[27]

Travels abroad

According to reports of the tsarist political police the Okhrana, Rosenblum was arrested in 1892 for political activities and for being a courier for a revolutionary group known as the Friends of Enlightenment. He escaped judicial punishment, and he later was friends with Okhrana agents such as Alexander Nikolayevich Grammatikov,[29] and these details might indicate that he was a police informant even at this young age.[b][29]

After Reilly's release, his father told him that his mother was dead and that his biological father was her Jewish doctor Mikhail A. Rosenblum.[18] Distraught by this news, he faked his death in Odessa harbor and stowed away aboard a British ship bound for South America.[30] In Brazil, he adopted the name Pedro and worked odd jobs as a dock worker, a road mender, a plantation laborer, and a cook for a British intelligence expedition in 1895.[30][18] He allegedly saved both the expedition and the life of Major Charles Fothergill when hostile natives attacked them.[31] Rosenblum seized a British officer's pistol and killed the attackers with expert marksmanship. Fothergill rewarded his bravery with 1,500 pounds sterling, a British passport, and passage to Britain, where Pedro became Sidney Rosenblum.[30]

However, the record of evidence contradicts this tale of Brazil.[32] Evidence indicates that Rosenblum arrived in London from France in December 1895, prompted by his unscrupulous acquisition of a large sum of money and a hasty departure from Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, a residential suburb of Paris.[32] According to this account, Rosenblum and his Polish accomplice Yan Voitek waylaid two Italian anarchists on 25 December 1895 and robbed them of a substantial amount of revolutionary funds. One anarchist's throat was cut; the other was named Constant Della Cassa, who died from knife wounds in Fontainebleau Hospital three days later.[32] The French newspaper L'Union Républicaine de Saône-et-Loire reported the incident on 27 December 1895:

A dramatic event occurred on a train between Paris and Fontainebleau.... On opening the door of one of the coaches, the railway staff discovered an unfortunate passenger lying unconscious in the middle of a pool of blood. His throat had been cut and his body bore the marks of numerous knife wounds. Terrified at the sight, the station staff hastened to inform the special investigator who started preliminary enquiries and sent the wounded man to the hospital in Fontainebleau.[33]

Police learned that the physical description of one assailant matched Rosenblum's, but he was already en route to Britain. His accomplice Voitek later told British intelligence officers about this incident and other dealings with Rosenblum.[32] Several months prior to this murder, Rosenblum had met Ethel Lilian Boole, a young Englishwoman[28][34] who was a budding writer and active in Russian émigré circles. The couple developed a rapport and began a sexual liaison,[35] and he told her about his past in Russia. After the affair concluded, they continued to correspond.[34] In 1897, Boole published The Gadfly, a critically acclaimed novel whose central character was allegedly based on Reilly's life as Rosenblum.[36] In the novel, the protagonist is a bastard who feigns his suicide to escape his illegitimate past, and then voyages to South America. He later returns to Europe and becomes involved with Italian anarchists and other revolutionaries.[36]

For decades, certain biographers had dismissed the Reilly-Boole liaison as unsubstantiated.[37] However, evidence was found in 2016 among archived correspondence in the extended Boole-Hinton family confirming that a relationship transpired between Reilly and Boole around 1895 in Florence.[35] There is some question of whether he was truly smitten with Boole and sincerely returned her affections, as he might have been a paid police informant reporting on her activities and those of other radicals.[37]

In London: 1890s

Reilly continued to go by the name Rosenblum, living at the Albert Mansions, an apartment block in Rosetta Street, Waterloo, London in early 1896.[39] He created the Ozone Preparations Company, which peddled patent medicines,[39] and he became a paid informant for the émigré intelligence network of William Melville, superintendent of Scotland Yard's Special Branch. (Melville later oversaw a special section of the British Secret Service Bureau founded in 1909.)[11][40]

In 1897, Rosenblum began an affair with Margaret Thomas (née Callaghan), the youthful wife of Reverend Hugh Thomas, shortly before her husband's death.[41][42] Rosenblum met Rev. Thomas in London through his Ozone Preparations Company[43] because Thomas had a kidney inflammation and was intrigued by the miracle cures peddled by Rosenblum. Rev. Thomas introduced Rosenblum to his wife at his manor house, and they began having an affair. On 4 March 1898, Hugh Thomas altered his will and appointed Margaret as an executrix; he was found dead in his room on 12 March 1898, just a week after the new will was made.[44] A mysterious Dr. T. W. Andrew, whose physical description matched that of Rosenblum, appeared to certify Thomas's death as generic influenza and proclaimed that there was no need for an inquest. Records indicate that there was no one by the name of Dr. T. W. Andrew in Great Britain circa 1897.[45][46]

Margaret Thomas insisted that her husband's body be ready for burial 36 hours after his death.[47] She inherited roughly £800,000. The Metropolitan Police did not investigate Dr. T. W. Andrew, nor did they investigate the nurse whom Margaret had hired, who was previously linked to the arsenic poisoning of a former employer.[47] Four months later, on 22 August 1898, Rosenblum married Margaret Thomas at Holborn Registry Office in London.[27] The two witnesses at the ceremony were Charles Richard Cross, a government official, and Joseph Bell, an Admiralty clerk. Both would eventually marry daughters of Henry Freeman Pannett, an associate of William Melville. The marriage not only brought the wealth which Rosenblum desired but provided a pretext to discard his identity of Sigmund Rosenblum; with Melville's assistance, he crafted a new identity: "Sidney George Reilly". This new identity was key to achieving his desire to return to the Russian Empire and voyage to the Far East.[38] Reilly "obtained his new identity and nationality without taking any legal steps to change his name and without making an official application for British citizenship, all of which suggests some type of official intervention."[48] This intervention most likely occurred to facilitate his upcoming work in Russia on behalf of British intelligence.[48]

Russia and the Far East

[Sidney Reilly's role] is one of the unsolved riddles about the Russo-Japanese War.[33]

— Ian H. Nish, The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War[49]

In June 1899, the newly endowed Sidney Reilly and his wife Margaret travelled to Emperor Nicholas II's Russian Empire using Reilly's (forged) British passport—a travel document and a cover identity both purportedly created by William Melville.[50] While in St. Petersburg he was approached by Japanese General Akashi Motojiro (1864–1919) to work for the Japanese Secret Intelligence Services.[51] A keen judge of character, Motojiro believed the most reliable spies were those who were motivated by profit instead of by feelings of sympathy towards Japan and, accordingly, he believed Reilly to be such a person.[51]

As tensions between Russia and Japan were escalating towards war, Motojiro had at his disposal a budget of one million yen provided by the Japanese Ministry of War to obtain information on the movements of Russian troops and naval developments.[51] Motojiro instructed Reilly to offer financial aid to Russian revolutionaries in exchange for information about the Russian Intelligence Services and, more importantly, to determine the strength of the Russian armed forces, particularly in the Far East.[33][2] Accepting Motojiro's recruitment overtures, Reilly now became simultaneously an agent for both the British War Office and the Japanese Empire.[2] While his wife Margaret remained in St. Petersburg, Reilly allegedly reconnoitred the Caucasus for its oil deposits and compiled a resource prospectus as part of "The Great Game". He reported his findings to the British Government, which paid him for the assignment.[25]

Shortly before the Russo-Japanese War, Reilly appeared in Port Arthur, Manchuria, in the guise of a timber company owner.[52][17] Here he remained for four years, familiarising himself with political conditions in the Far East and obtaining a degree of personal influence in the ongoing espionage activities in the region.[22] At the time he was still a double agent for the British and the Japanese governments.[18][52] The Russian-controlled Port Arthur lay under the ever-darkening spectre of a Japanese invasion, and Reilly and his business partner Moisei Akimovich Ginsburg turned the precarious situation to their benefit. By purchasing and reselling enormous amounts of foodstuffs, raw materials, medicine, and coal, they made a small fortune as war profiteers.[53]

Reilly would have an even greater success in January 1904, when he and Chinese engineer acquaintance Ho Liang Shung allegedly stole the Port Arthur harbour defence plans for the Japanese Navy.[51] Guided by these stolen plans, the Japanese Navy navigated by night through the Russian minefield protecting the harbour and launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur on the night of 8–9 February 1904 (Monday 8 February – Tuesday 9 February). However, the stolen plans did not help the Japanese much. Despite ideal conditions for a surprise attack, their combat results were relatively poor. Although more than 31,000 Russians ultimately perished defending Port Arthur, Japanese losses were much higher, and these losses nearly undermined their war effort.[54]

According to writer Winfried Lüdecke,[c] Reilly quickly became an obvious target of suspicion by Russian authorities at Port Arthur.[52] Thereafter, he discovered one of his business subordinates was an agent of Russian counter-espionage and chose to leave the region.[52] Upon departing Port Arthur, Reilly travelled to Imperial Japan in the company of an unidentified woman where he was handsomely paid by the Japanese government for his prior intelligence services.[52] If he made a detour to Japan, presumably to be paid for his espionage, he could not have stayed very long, for by February 1905 he appeared in Paris.[55] By the time he had returned to Europe from the Far East, Reilly "had become a self-confident international adventurer" who was "fluent in several languages" and whose intelligence services were highly desired by various great powers.[17] At the same time, he was described as possessing "a foolhardy adventurous nature" prone to taking unnecessary risks.[19] This latter trait would later result in him being nicknamed "reckless" by other British agents.[6]

Continental exploits

D'Arcy affair

During the brief time Reilly spent in Paris he renewed his close acquaintance with William Melville[d] whom Reilly had last seen just prior to his 1899 departure from London.[57] While Reilly had been abroad in the Far East, Melville had resigned in November 1903 as Superintendent of Scotland Yard's Special Branch and had become chief of a new intelligence section in the War Office.[58] Working under commercial cover from an unassuming flat in London, Melville now ran both counter-intelligence and foreign intelligence operations using his foreign contacts which he had accumulated during his years running Special Branch.[58] Reilly's meeting with Melville in Paris is most significant, for within a matter of weeks Melville was to use Reilly's expertise in what would later become known as the D'Arcy Affair.[57]

In 1904 the Board of the Admiralty projected that petroleum would supplant coal as the primary source of fuel for the Royal Navy. As petroleum was not abundant in Britain, it would be necessary to find—and secure—sufficient supplies overseas. During their investigation the British Admiralty learned that an Australian mining engineer William Knox D'Arcy—who founded the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC)—had obtained a valuable concession from Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar regarding oil rights in southern Persia.[15] D'Arcy was negotiating a similar concession from the Ottoman Empire for oil rights in Mesopotamia.[57] The Admiralty initiated efforts to entice D'Arcy to sell his newly acquired oil rights to the British Government rather than to the French de Rothschilds.[57][59]

Reilly, at the British Admiralty's request, located William D'Arcy at Cannes in the south of France and approached him in disguise.[60] Dressed as a Catholic priest, Reilly gate-crashed the private discussions on board the Rothschild yacht on the pretext of collecting donations for a religious charity.[60] He then secretly informed D'Arcy that the British could give him a better financial deal.[15] D'Arcy promptly terminated negotiations with the Rothschilds and returned to London to meet with the British Admiralty.[5] However, biographer Andrew Cook has questioned Reilly's involvement in the D'Arcy Affair since, in February 1904, Reilly might still have been in Port Arthur. Cook speculates that it was Reilly's intelligence chief, William Melville, and a British intelligence officer, Henry Curtis Bennett, who undertook the D'Arcy assignment.[61] Yet another possibility advanced in The Prize by writer Daniel Yergin has the British Admiralty creating a "syndicate of patriots" to keep D'Arcy's concession in British hands, apparently with the full and eager co-operation of D'Arcy himself.[59]

Although the extent of Reilly's involvement in this particular incident is uncertain, it has been verified that he stayed after the incident in the French Riviera on the Côte d'Azur, a location very near the Rothschild yacht.[62] At the conclusion of the D'Arcy Affair, Reilly journeyed to Brussels, and, in January 1905, he returned to St. Petersburg, Russia.[62]

Frankfurt Air Show

In Ace of Spies, biographer Robin Bruce Lockhart recounts Reilly's alleged involvement in obtaining a newly developed German magneto at the first Frankfurt International Air Show ("Internationale Luftschiffahrt-Ausstellung") in 1909.[63] According to Lockhart, on the fifth day of the air show in Frankfurt am Main, a German plane lost control and crashed, killing the pilot. The plane's engine was alleged to have used a new type of magneto that was far ahead of other designs.[63]

Reilly and a British SIS agent posing as one of the exhibition pilots diverted the attention of spectators while they removed the magneto from the wreck and substituted another.[63] The SIS agent quickly made detailed drawings of the German magneto, and when the airplane had been removed to a hangar, the agent and Reilly managed to restore the original magneto.[63][64][61] However, later biographers such as Spence and Cook have countered that this incident is unsubstantiated.[64] There is no documentary evidence of any plane crashes occurring during the event.[61]

Stealing weapon plans

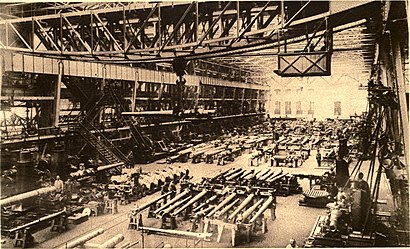

In 1909, when the German Kaiser was expanding the war machine of Imperial Germany, British intelligence had scant knowledge regarding the types of weapons being forged inside Germany's war plants. At the behest of British intelligence, Reilly was sent to obtain the plans for the weapons.[65] Reilly arrived in Essen, Germany, disguised as a Baltic shipyard worker by the name of Karl Hahn. Having prepared his cover identity by learning to weld at a Sheffield engineering firm,[66] Reilly obtained a low-level position as a welder at the Krupp Gun Works plant in Essen. Soon he joined the plant fire brigade and persuaded its foreman that a set of plant schematics were needed to indicate the position of fire extinguishers and hydrants. These schematics were soon lodged in the foreman's office for members of the fire brigade to consult, and Reilly set about using them to locate the plans.[65]

In the early morning hours, Reilly picked the lock of the office where the plans were kept and was discovered by the foreman whom he then strangled before completing the theft. From Essen, Reilly took a train to a safe house in Dortmund. Tearing the plans into four pieces, he mailed each separately so that if one were lost, the other three would still reveal the essence of the plans.[65] Biographer Cook questions the veracity of this incident but concedes that German factory records show a Karl Hahn was indeed employed by the Essen plant during this time and that a plant fire brigade existed.[67][dubious – discuss]

In April 1912, Reilly returned to St. Petersburg where he assumed the role of a wealthy businessman and helped to form the Wings Aviation Club. He resumed his friendship with Alexander Grammatikov who was an Okhrana agent and a fellow member of the club.[29] Writers Richard Deacon and Edward Van Der Rhoer assert that Reilly was an Ochrana double agent at this point.[3][68] Deacon claims he was tasked with befriending and profiling Sir Basil Zaharoff, the international arms salesman and representative of Vickers-Armstrong Munitions Ltd.[3] Another Reilly biographer, Richard B. Spence, claims that during this assignment Reilly learned "le systeme" from Zaharoff—the strategy of playing all sides against each other to maximise financial profit.[69] However, biographer Andrew Cook asserts there is scant evidence of any relationship between Reilly and Zaharoff.[70]

First World War activity

"Reilly was dropped by plane many times behind the German lines; sometimes in Belgium, sometimes in Germany, sometimes disguised as a peasant, sometimes as a German officer or soldier, when he usually carried forged papers to indicate he had been wounded and was on sick-leave from the front. In this way he was able to move throughout Germany with complete freedom."[71]

In earlier biographies by Winfried Lüdecke and Pepita Bobadilla, Reilly is described as living as a spy in Wilhelmine Germany from 1917 to 1918.[52][22] Drawing upon the latter sources, Richard Deacon likewise asserted that Reilly had operated behind German lines on a number of occasions and once spent weeks inside the German Empire gathering information about the next planned thrust against the Allies.[72] However, most later biographies concur that Reilly's activities in the United States between 1915 and 1918 precluded any such escapades on the European Front.[73] Later biographers believe that Reilly, while lucratively engaged in the munitions business in New York City, was covertly employed in British intelligence in which role he may well have participated in several acts of so-called "German sabotage" deliberately calculated to provoke the United States to enter the war against the Central Powers.[74]

Historian Christopher Andrew notes that "Reilly spent most of the first two and a half years of the war in the United States".[73] Likewise, author Richard B. Spence states that Reilly lived in New York City for at least a year, 1914–15, where he engaged in arranging munitions sales to the Imperial German Army and its enemy the Imperial Russian Army.[75] However, when the United States entered the war in April 1917, Reilly's business became less profitable since his company was now prohibited from selling ammunition to the Germans and, after the Russian revolution occurred in October 1917, the Russians were no longer buying munitions. Faced with unexpected financial hardship, Reilly sought to resume his paid intelligence work for the British government while in New York City.[76]

This is confirmed by papers of Norman Thwaites, MI1(c) Head of Station in New York,[77] which contain evidence that Reilly approached Thwaites seeking espionage-related work in 1917–1918.[78] Formerly a private secretary to newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer and a police reporter for Pulitzer's The New York World,[77] Thwaites was keen on obtaining information concerning radical activities in the United States; in particular, any connections between American socialists with Soviet Russia.[77] Consequently, under Thwaites' direction, Reilly presumably worked alongside a dozen other British intelligence operatives attached to the British mission at 44 Whitehall Street in New York City.[78][77] Although their ostensible mission was to coordinate with the U.S. government in regards to intelligence about the German Empire and Soviet Russia, the British agents also focused upon obtaining trade secrets and other commercial information related to American industrial companies for their British rivals.[77]

Thwaites was sufficiently impressed with Reilly's intelligence work in New York that he wrote a letter of recommendation to Mansfield Cumming, head of MI1(c). It was also Thwaites who recommended that Reilly first visit Toronto to obtain a military commission which is why Reilly enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps Canada.[79] On 19 October 1917, Reilly received a commission as a temporary second lieutenant on probation.[80] After receiving this commission, Reilly voyaged to London in 1918 where Cumming formally swore Lieutenant Reilly into service as a staff Case Officer in His Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), prior to dispatching Reilly on counter-Bolshevik operations in Germany and Russia.[79] According to Reilly's wife Pepita Bobadilla, Reilly was sent to Russia to "counter the work being done there by German agents" who were supporting radical factions and "to discover and report on the general feeling".[9]

Thus Reilly arrived on Russian soil via Murmansk prior to 5 April 1918.[81] Reilly contacted the former Okhrana agent Alexander Grammatikov, who believed the Soviet government "was in the hands of the criminal classes and of lunatics released from the asylums".[29] Grammatikov arranged for Reilly to receive a private interview with either Reilly's longtime friend[82] General Mikhail Bonch-Bruyevich[83] or Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich,[84] secretary of the Council of People's Commissars.[e] With the clandestine aid of Bonch-Bruyevich,[83] he assumed the role of a Bolshevik sympathizer.[81] Grammatikov further instructed his niece Dagmara Karozus[87]—a dancer in the Moscow Art Theatre—to allow Reilly to use her apartment as a "safe house", and through Vladimir Orlov, a former Okhrana associate turned Cheka official, Reilly obtained travel permits as a Cheka agent.[88][89]

Ambassadors' plot

In 1918, behind-the-scenes helpers such as ... Sidney Reilly, the erstwhile Russian double agent who was operating on Britain's behalf, were involved in the formulation and execution of various attempts to snatch both Russia and the [Romanov family] from the Bolsheviks.[4]

— Shay McNeal, historical researcher on Russian history and contributor to BBC[90]

The attempt to assassinate Vladimir Lenin and to depose the Bolshevik government is considered by biographers to be Reilly's most daring exploit.[91][92] The Ambassadors' Plot, later misnamed in the press as the Lockhart-Reilly Plot,[93][94] has sparked considerable debate over the years: did the Allies launch a clandestine operation to overthrow the Bolsheviks in the later summer of 1918 and, if so, did Felix Dzerzhinsky's Cheka uncover the plot at the eleventh hour or did they know of the conspiracy from the outset?[95][91] At the time, the dissembling American Consul-General DeWitt Clinton Poole publicly insisted the Cheka orchestrated the conspiracy from beginning to end and that Reilly was a Bolshevik agent provocateur.[f][96][12] Later, Robert Bruce Lockhart would state that he was "not to this day sure of the extent of Reilly's responsibility for the disastrous turn of events."[9]

In January 1918, the youthful Lockhart—a mere junior member of the British Foreign office—had been personally handpicked by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George to undertake a sensitive diplomatic mission to Soviet Russia.[97] Lockhart's assigned objectives were: to liaise with the Soviet authorities, to subvert Soviet-German relations, to bolster Soviet resistance to German peace overtures, and to push Soviet authorities into recreating the Eastern Theater.[97] By April, however, Lockhart had hopelessly failed to achieve any of these objectives. He began to agitate in diplomatic cables for an immediate full-scale Allied military intervention in Russia.[97] Concurrently, Lockhart ordered Sidney Reilly to pursue contacts within anti-Bolshevik circles to sow the seeds for an armed uprising in Moscow.[98][97]

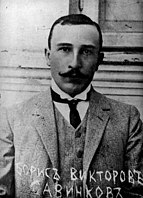

In May 1918, Lockhart, Reilly, and various agents of the Allied Powers repeatedly met with Boris Savinkov,[10] head of the counter-revolutionary Union for the Defence of the Motherland and Freedom (UDMF).[99] Savinkov had been Deputy War Minister in the Provisional Government of Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, and a key opponent of the Bolsheviks.[100] A former Socialist Revolutionary Party member, Savinkov had formed the UDMF consisting of several thousand Russian fighters, and he was receptive to Allied overtures to depose the Soviet government.[100] Lockhart, Reilly, and others then contacted anti-Bolshevik groups linked to Savinkov and Socialist Revolutionary Party cells affiliated with Savinkov's friend Maximilian Filonenko. Lockhart and Reilly supported these factions with SIS funds.[10] They also liaised with DeWitt Clinton Poole and Fernand Grenard,[74] the Consuls-General of the United States and France respectively.[74] They also coordinated their activities with intelligence operatives affiliated with the French and U.S. consuls in Moscow.[23][101]

Planning a coup

In June, disillusioned elements of Colonel Eduard Berzin's Latvian Rifle Division (Latdiviziya) began appearing in anti-Bolshevik circles in Petrograd and were eventually directed to a British naval attaché Captain Francis Cromie and his assistant Mr. Constantine, a Turkish merchant who was actually Reilly.[101] In contrast to his previous espionage operations which had been independent of other agents, Reilly worked closely while in Petrograd with Cromie in joint efforts to recruit Berzin's Latvians and to equip anti-Bolshevik armed forces.[102] At the time, Cromie purportedly represented the British Naval Intelligence Division and oversaw its operations in northern Russia.[103] Cromie operated in loose coordination with the ineffectual Commander Ernest Boyce, the MI1(c) station chief in Petrograd.[103]

As Berzin's Latvians were deemed the Praetorian Guard of the Bolsheviks and entrusted with the security of both Lenin and the Kremlin, the Allied plotters believed their participation in the pending coup to be vital. With the aid of the Latvian Riflemen, the Allied agents hoped to "seize both Lenin and Trotsky at a meeting to take place in the first week of September".[9]

Reilly arranged a meeting between Lockhart and the Latvians at the British mission in Moscow. Reilly purportedly expended "over a million rubles" to bribe the Red Army troops guarding the Kremlin.[94] At this stage, Cromie,[103] Boyce,[74] Reilly,[104] Lockhart, and other Allied agents allegedly planned a full-scale coup against the Bolshevik government and drew up a list of Soviet military leaders ready to assume responsibilities on its demise.[105] Their objective was to capture or kill Lenin and Trotsky, to establish a provisional government, and to extinguish Bolshevism.[9] Lenin and Trotsky, they reasoned, "were Bolshevism", and nothing else in their movement had "substance or permanence".[9] Consequently, "if he could get them into [their] hands there would be nothing of consequence left of Sovietism".[9]

As Lockhart's diplomatic status hindered his open engagement in clandestine activities, he chose to supervise such activities from afar and to delegate the actual direction of the coup to Reilly.[106] To facilitate this work, Reilly allegedly obtained a position as a sinecure within the criminal branch of the Petrograd Cheka.[106] It was during this chaotic time of plots and counter-plots that Reilly and Lockhart became further acquainted.[12] Lockhart later posthumously described him as "a man of great energy and personal charm, very attractive to women and very ambitious. I had not a very high opinion of his intelligence. His knowledge covered many subjects, from politics to art, but it was superficial. On the other hand, his courage and indifference to danger were superb."[12] Throughout their backroom intrigues in Moscow, Lockhart never openly questioned Reilly's loyalty to the Allies, although he privately wondered if Reilly had made a secret bargain with Colonel Berzin and his Latvian Riflemen to later seize power for themselves.[12]

In Lockhart's estimation, Reilly was a limitless "man cast in the Napoleonic mold" and, if their counter-revolutionary coup had succeeded, "the prospect of playing a lone hand [using Berzin's Latvian Riflemen] may have inspired him with a Napoleonic design" to become the head of any new government.[12] However, unbeknownst to the Allied conspirators, Berzin was "an honest commander" and "devoted to the Soviet government".[107] Although not a Chekist, he nonetheless informed Dzerzhinsky's Cheka that he had been approached by Reilly and that Allied agents had attempted to recruit him into a possible coup.[107] This information did not surprise Dzerzhinsky as the Cheka had gained access to the British diplomatic codes in May and were closely monitoring the anti-Bolshevik activities.[102] Dzerzhinsky instructed Berzin and other Latvian officers to pretend to be receptive to the Allied plotters and to meticuously report on every detail of their pending operation.[107]

The plot unravels

While Allied agents militated against the Soviet regime in Petrograd and Moscow, persistent rumors swirled of an impending Allied military intervention in Russia which would overthrow the fledgling Soviet government in favor of a new regime willing to rejoin the ongoing war against the Central Powers.[94] On 4 August 1918, an Allied force landed at Arkhangelsk, Russia, beginning a famous military expedition dubbed Operation Archangel. Its professed objective was to prevent the German Empire from obtaining Allied military supplies stored in the region. In retaliation for this incursion, the Bolsheviks raided the British diplomatic mission on 5 August, disrupting a meeting Reilly had arranged between the anti-Bolshevik Latvians, UDMF officials, and Lockhart.[105] Unperturbed by these raids, Reilly conducted meetings on 17 August 1918 between Latvian regimental leaders and liaised with Captain George Alexander Hill, a multilingual British agent operating in Russia on behalf of the Military Intelligence Directorate.[108][109]

Hill later described Reilly as "a dark, well-groomed, very foreign-looking man" who had "an amazing grasp of the actualities of the situation" and was "a man of action".[8] They agreed the coup would occur in the first week of September during a meeting of the Council of People's Commissars and the Moscow Soviet at the Bolshoi Theatre.[105] On 25 August, yet another meeting of Allied conspirators allegedly occurred at DeWitt C. Poole's American Consulate in Moscow.[94] By this time, the Allied conspirators had organized a broad network of agents and saboteurs throughout Soviet Russia whose overarching ambition was to disrupt the nation's food supplies. Coupled with the planned military uprising in Moscow, they believed a chronic food shortage would trigger popular unrest and further undermine the Soviet authorities. In turn, the Soviets would be overthrown by a new government friendly to the Allied Powers which would renew hostilities against Kaiser Wilhelm II's German Reich.[95] On 28 August, Reilly informed Hill that he was immediately leaving Moscow for Petrograd where he would discuss final details related to the coup with Commander Francis Cromie at the British consulate.[110] That night, Reilly had no difficulty in traveling through picket lines between Moscow and Petrograd due to his identification as a member of the Petrograd Cheka and his possession of Cheka travel permits.[110]

On 30 August, Boris Savinkov and Maximilian Filonenko ordered a military cadet named Leonid Kannegisser—Filonenko's cousin—to shoot and kill Moisei Uritsky, head of the Petrograd Cheka.[111] Uritsky had been the second most powerful man in the city after Grigory Zinoviev, the leader of the Petrograd Soviet, and his murder was seen as a blow to both the Cheka and the entire Bolshevik leadership.[103] After killing Uritsky, a panicked Kannegisser sought refuge either at the English Club[103] or at the British mission where Cromie resided and where Savinkov and Filonenko may have been temporarily in hiding.[112][113] Regardless of whether he fled to the English Club or to the British consulate, Kannegisser was compelled to leave the premises. After donning a long overcoat, he fled into the city streets where he was apprehended by Red Guards after a violent shootout.

On the same day, Fanya Kaplan—a former anarchist who was now a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party[114]—shot and wounded Lenin as he departed the Michelson arms factory in Moscow.[114] As Lenin exited the building and before he entered his motor car, Kaplan called out to him. When Lenin turned towards her, she fired three shots with a Browning pistol.[115] One bullet narrowly missed Lenin's heart and penetrated his lung, while the other bullet lodged in his neck near the jugular vein.[111] Due to the severity of these wounds, Lenin was not expected to survive.[111][103] The attack was widely covered in the Russian press, generating much sympathy for Lenin and boosting his popularity.[116] As a consequence of this assassination attempt, however, the meeting between Lenin and Trotsky—where the bribed soldiery would seize them on behalf of the Allies—was postponed.[9] At this point, Reilly was notified by fellow conspirator Alexander Grammatikov that "the [Socialist Revolutionary Party] fools have struck too early".[85]

Chekist reprisal

Although it is unknown if Kaplan either was part of the Ambassadors' Plot or was even responsible for the assassination attempt on Lenin,[g] the murder of Uritsky and the failed assassination of Lenin were used by Dzerzhinsky's Cheka to implicate any malcontents and foreigners in a grand conspiracy that warranted a full-scale reprisal campaign: the "Red Terror".[118] Thousands of political opponents were seized and "mass executions took place across the city, at Khodynskoe field, Petrovsky Park and the Butyrki prison, all in the north of the city, as well as in the Cheka headquarters at Lubyanka".[118] The extent of the Chekist reprisal likely foiled much of the inchoate plans by Cromie, Boyce, Lockhart, Reilly, Savinkov, Filonenko, and other conspirators.[105][103]

Using lists supplied by undercover agents, the Cheka proceeded to clear out the "nests of conspirators" in the foreign embassies and, in doing so, they arrested key figures vital to the impending coup.[103][9] On 31 August 1918, believing Savinkov and Filonenko were hiding in the British consulate,[112][113] a Cheka detachment raided the British consulate in Petrograd and killed Cromie who put up an armed resistance.[119][112][113] Immediately prior to his death, it is possible that Cromie may have been trying to communicate with other conspirators and to give instructions to accelerate their planned coup.[103] Before the Cheka detachment stormed the consulate, Cromie burned key correspondence pertaining to the coup.[103]

According to press reports, he made a valiant last stand on the first floor of the consulate armed only with a revolver.[119] In close quarters combat, he dispatched three Chekist soldiers before he was in turn killed and his corpse mutilated.[119][112] Eyewitnesses, such as the sister-in-law of Red Cross nurse Mary Britnieva, asserted that Cromie was shot by the Cheka while retreating down the consulate's grand staircase.[120] The Cheka detachment searched the building and, with their rifle butts, repelled the diplomatic staff from getting close to the corpse of Captain Cromie which the Chekist soldiers had looted and trampled.[103] The Cheka detachment then arrested over forty persons who had sought refuge within the British consulate, as well as seized weapon caches and compromising documents which they claimed implicated the consular staff in the forthcoming coup attempt.[119][23] Cromie's death was publicly "depicted as a measure of self-defence by the Bolshevik agents, who had been forced to return his fire".[23]

Meanwhile, Lockhart was arrested by Dzerzhinsky's Cheka and transported under guard to Lubyanka Prison.[111] During a tense interview with a pistol-wielding Cheka officer, he was asked "Do you know the Kaplan woman?" and "Where is Reilly?"[111] When queried about the coup, Lockhart and other British nationals dismissed the mere idea as nonsense.[10] Afterwards, Lockhart was placed in the same holding cell as Fanya Kaplan whom their watchful Chekist jailers hoped might betray some sign of recognizing Lockhart or other British agents.[121] However, while confined together, Kaplan showed no sign of recognition towards Lockhart or anyone else.[121] When it became clear that Kaplan would not implicate any accomplices, she was executed in the Kremlin's Alexander Garden on 3 September 1918, with a bullet to the back of the head.[115] Her corpse was bundled into a rusted iron barrel and set alight.[115] Lockhart was later released and deported in exchange for Maxim Litvinov, an unofficial Soviet attaché in London who had been arrested by the British government as a form of diplomatic reprisal.[122] In stark contrast to Lockhart's good fortune, "imprisonment, torture to compel confession, [and] death were the swift rewards of many who had been implicated" in the prospective coup against Lenin's government.[9] Yelizaveta Otten, Reilly's chief courier "with whom he was romantically involved,"[123] was arrested as well as his other mistress Olga Starzheskaya.[81] After interrogation, Starzheskaya was imprisoned for five years.[81] Yet another courier, Mariya Fride, likewise was arrested at Otten's flat with an intelligence communiqué that she was carrying for Reilly.[124][125][105]

Escape from Russia

On 3 September 1918 the Pravda and Izvestiya newspapers sensationalised the aborted coup on their front pages.[94][23] Outraged headlines denounced the Allied representatives and other foreigners in Moscow as "Anglo-French Bandits".[23] The papers arrogated credit for the coup to Reilly and, when he was identified as a key suspect, a dragnet ensued.[94] Reilly "was hunted through days and nights as he had never been hunted before,"[9] and "his photograph with a full description and a reward was placarded" throughout the area.[126] The Cheka raided his assumed refuge, but the elusive Reilly avoided capture and met Captain Hill while in hiding.[126] Hill later wrote that Reilly, despite narrowly escaping his pursuers in both Moscow and Petrograd, "was absolutely cool, calm and collected, not in the least downhearted and only concerned in gathering together the broken threads and starting afresh".[126]

Hill proposed that Reilly escape from Russia via Ukraine to Baku using their network of British agents for safe houses and assistance.[126] However, Reilly instead chose a shorter, more dangerous route north through Petrograd and the Baltic Provinces to Finland to get their reports to London as early as possible.[126] With the Cheka closing in, Reilly, carrying a Baltic German passport supplied by Hill, posed as a legation secretary and departed the region in a railway car reserved for the German Embassy. In Kronstadt, Reilly sailed by ship to Helsinki and reached Stockholm with the aid of local Baltic smugglers.[127] He arrived unscathed in London on 8 November.[127]

While safely in England, Reilly, Lockhart and other agents were tried in absentia before the Supreme Revolutionary Tribunal in a proceeding which opened 25 November 1918.[128] Approximately twenty defendants faced charges in the trial, most of whom had worked for the Americans or the British in Moscow. The case was prosecuted by Nikolai Krylenko,[h] an exponent of the theory that political considerations rather than criminal guilt should decide a case's outcome.[129][128]

Krylenko's case concluded on 3 December 1918, with two defendants sentenced to be shot and various others sentenced to terms of prison or forced labour for terms up to five years.[128] Thus, the day before Reilly met Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming ("C") in London for debriefing, the Russian Izvestia newspaper reported that both Reilly and Lockhart had been sentenced to death in absentia by a Revolutionary Tribunal for their roles in the attempted coup of the Bolshevik government.[128][131] The sentence was to be carried out immediately should either of them be apprehended on Soviet soil. This sentence would later be served on Reilly when he was caught by Dzerzhinsky's OGPU in 1925.[128][132]

Activities from 1919 to 1924

Russian Civil War

Within a week of their return debriefing, the British Secret Intelligence Service and the Foreign Office again sent Reilly and Hill to South Russia under the cover of British trade delegates. Their assignment was to uncover information about the Black Sea coast needed for the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.[134] At that time the region was home to a variety of anti-Bolsheviks. They travelled in the guise of British merchants, with appropriate credentials provided by the Department of Overseas Trade. Over the next six weeks or so Reilly prepared twelve dispatches which reported on various aspects of the situation in South Russia and were delivered personally by Hill to the Foreign Office in London.

Reilly identified four principal factors in the affairs of South Russia at this time: the Volunteer Army; the territorial or provincial governments in the Kuban, Don, and Crimea; the Petlyura movement in Ukraine; and the economic situation. In his opinion, the future course of events in this region would depend not only on the interaction of these factors with each other, but "above all upon Allied attitude towards them". Reilly advocated Allied assistance to organise South Russia into a suitable place d'armes for decisive advance against Petlurism and Bolshevism. In his opinion: "The military Allied assistance required for this would be comparatively small as proved by recent events in Odessa. Landing parties in the ports and detachments assisting Volunteer Army on lines of communication would probably be sufficient."[135]

Reilly's reference to events in Odessa concerned the successful landing there on 18 December 1918 of troops from the French 156th Division commanded by General Borius, who managed to wrest control of the city from the Petlyurists with the assistance of a small contingent of Volunteers.[135]

Urgent as the need for Allied military assistance to the Volunteer Army was in Reilly's estimation, he regarded economic assistance for South Russia as "even more pressing". Manufactured goods were so scarce in this region that he considered any moderate contribution from the Allies would have a most beneficial effect. Otherwise, apart from echoing a certain General Poole's suggestion for a British or Anglo-French Commission to control merchant shipping engaged in trading activities in the Black Sea, Reilly did not offer any solutions to what he called a state of "general economic chaos" in South Russia. Reilly found White officials, who had been given the job of helping the Russian economy get better, "helpless" in coming to terms with "the colossal disaster which has overtaken Russia's finances, ... and unable to frame anything, approaching even an outline, of a financial policy". But he supported their request for the Allies to print "500 Million roubles of Nicholas money of all denominations" for the Special Council as a matter of urgency, with the justification that "although one realises the fundamental futility of this remedy, one must agree with them that for the moment this is the only remedy". Lack of funds was one reason offered by Reilly to explain the Whites' blatant inactivity in the propaganda field. They were also said to be lacking paper and printing presses needed for the preparation of propaganda material. Reilly claimed that the Special Council had come to appreciate fully the benefits of propaganda.[135]

Final marriage

While on a visit to postwar Berlin in December 1922, Reilly met a charming young actress named Pepita Bobadilla in the Hotel Adlon. Bobadilla was an attractive blonde who falsely claimed to be from South America.[136] Her real name was Nelly Burton, and she was the widow of Charles Haddon Chambers,[137] a well-known British playwright. For the past several years Bobadilla had gained notoriety both as Chambers' wife and for her stage career as a dancer.[136] On 18 May 1923, after a whirlwind romance, Bobadilla married Reilly at a civil Registry Office on Henrietta Street, in Covent Garden, Central London, with Captain Hill acting as a witness.[138][9] As Reilly was already married at the time, their union was bigamous. Bobadilla later described Reilly as a sombre individual and found it strange that he never entertained guests at their home. Except for two or three acquaintances, hardly anyone could boast of being his friend.[22] Nevertheless, their marriage was reportedly happy as Bobadilla believed Reilly to be "romantic", "a good companion", "a man of infinite courage", and "the ideal husband".[22] Their union would last merely 30 months before Reilly's disappearance in Russia and his execution by the Soviet OGPU.

Zinoviev scandal

One year later Reilly was involved—possibly alongside Sir Stewart Graham Menzies[139]—in the international scandal known as the Zinoviev Letter.[6][7][139] Four days before the British general election on 8 October 1924, a Tory newspaper printed a letter purporting to originate from Grigory Zinoviev, head of the Third Communist International.[6] The letter claimed the planned resumption of diplomatic and trade relations by the Labour party with Soviet Russia would indirectly hasten the overthrow of the British government.[140] Mere hours later the British Foreign Office incorporated this letter in a stiff note of protest to the Soviet government.[6] Soviet Russia and British Communists denounced the letter as a forgery by British intelligence agents, while Conservative politicians and newspapers maintained the document was genuine.[citation needed] Recent scholarship argues that the Zinoviev letter was indeed a forgery.[139][citation needed]

Amid the uproar following the printing of the letter and the Foreign Office protest, Ramsay MacDonald's Labour Government lost the general election.[6] According to Samuel T. Williamson, writing in The New York Times in 1926, Reilly may have served as a courier to transport the forged Zinoviev letter into the United Kingdom.[6][139] Reflecting upon these events, the journalist Winfried Lüdecke[c] posited in 1929 that Reilly's role in "the famous Zinoviev letter assumed a world-wide political importance, for its publication in the British press brought about the fall of the [Ramsay] Macdonald ministry, frustrated the realization of the proposed Anglo-Russian commercial treaty, and, as a final result, led to the signing of the treaties of Locarno, in virtue of which the other states of Europe presented, under the leadership of Britain, a united front against Soviet Russia".[7]

Career with British intelligence

[Mansfield] Cumming's most remarkable, though not his most reliable, agent was Sidney Reilly, the dominating figure in the mythology of modern British espionage. Reilly, it has been claimed, 'wielded more power, authority and influence than any other spy,' was an expert assassin 'by poisoning, stabbing, shooting and throttling,' and possessed eleven passports and a wife to go with each.[17]

— Christopher Andrew, emeritus professor at the University of Cambridge, Her Majesty's Secret Service (1985)

Throughout his life, Sidney Reilly maintained a close yet tempestuous relationship with the British intelligence community. In 1896, Reilly was recruited by Superintendent William Melville for the émigré intelligence network of Scotland Yard's Special Branch. Through his close relationship with Melville, Reilly would be employed as a secret agent for the Secret Service Bureau, which the Foreign Office created in October 1909.[11] In 1918, Reilly began to work for MI1(c), an early designation[11] for the British Secret Intelligence Service, under Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming. Reilly was allegedly trained by the latter organization and sent to Moscow in March 1918 to assassinate Vladimir Ilyich Lenin or attempt to overthrow the Bolsheviks.[10] He had to escape after the Cheka unraveled the so-called Lockhart Plot against the Bolshevik government. Later biographies contain numerous tales about his espionage deeds. It has been claimed that:

- In the Boer War he masqueraded as a Russian arms merchant to spy on Dutch weapons shipments to the Boers.[141]

- He obtained intelligence on Russian military defences in Manchuria for the Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police.[17]

- He procured Persian oil concessions for the British Admiralty in events surrounding the D'Arcy Concession.[5]

- He infiltrated a Krupp armaments plant in prewar Germany and stole weapon plans for the Entente Powers.[141]

- He seduced the wife of a Russian minister to glean information about German weapons shipments to Russia.[15]

- He participated in missions of so-called "German sabotage" designed to draw the United States into World War I.[74]

- He attempted to overthrow the Russian Bolshevik government and to rescue the imprisoned Romanov family.[4]

- Prior to his demise, he served as a courier to transport the forged Zinoviev letter into the United Kingdom.[6][139]

British intelligence adhered to its policy of publicly saying nothing about anything.[1] Yet Reilly's espionage successes did garner indirect recognition. After a formal recommendation by Sir Mansfield "C" Smith-Cumming, Reilly, who had received a military commission in 1917, was awarded the Military Cross on 22 January 1919, "for distinguished services rendered in connection with military operations in the field".[142][143] This vaguely-worded citation misled later biographers such as Richard Deacon to wrongly conclude that Reilly's medal was bestowed for valorous military feats against the Imperial German Army during the Great War of 1914–1918[72] however most later biographers agree the medal was bestowed due to Reilly's anti-Bolshevik operations in southern Russia.[i]

Reilly's most skeptical biographer, Andrew Cook, asserts that Reilly's SIS-specific career has been greatly embellished as he wasn't accepted as an agent until 15 March 1918. He was then discharged in 1921 because of his tendency to be a rogue operative. Nevertheless, Cook concedes that Reilly previously had been a renowned operative for Scotland Yard's Special Branch and the Secret Service Bureau which were the early forerunners of the British intelligence community. Historian Christopher Andrew, a professor at University of Cambridge with a focus on the history of the intelligence services, described Reilly's secret service career overall as "remarkable, though largely ineffective".[144][27]

Execution and death

According to Reilly's wife Pepita Bobadilla, Reilly was perpetually determined "to return to Russia to see if he could not find and succor some of his friends whom he believed to be still alive. This he did in 1925—and never came back."[9] In September 1925 in Paris, Reilly met Alexander Grammatikov, White Russian General Alexander Kutepov, counter-espionage expert Vladimir Burtsev, and Commander Ernest Boyce from British Intelligence.[145] This assembly discussed how they could make contact with a supposedly pro-Monarchist, anti-Bolshevik organisation known as "The Trust" in Moscow.[145] The assembly agreed that Reilly should journey to Finland to explore the feasibility of yet another uprising in Russia using The Trust apparatus.[145] However, in reality The Trust was an elaborate counter-espionage deception created by the OGPU, the intelligence successor of the Cheka.[146][147]

Thus, undercover agents of the OGPU lured Reilly into Bolshevik Russia, ostensibly to meet with supposed anti-Communist revolutionaries. At the Soviet-Finnish border Reilly was introduced to undercover OGPU agents posing as senior Trust representatives from Moscow. One of these undercover Soviet agents, Alexander Alexandrovich Yakushev, later recalled the meeting:

The first impression of [Sidney Reilly] is unpleasant. His dark eyes expressed something biting and cruel; his lower lip drooped deeply and was too slick—the neat black hair, the demonstratively elegant suit. ... Everything in his manner expressed something haughtily indifferent to his surroundings.[148]

Reilly was brought across the border by Toivo Vähä, a former Finnish Red Guard fighter who now served the OGPU. Vähä took Reilly over the Sestra River to the Soviet side and handed him to the OGPU officers.[149][150] (In the 1973 book The Gulag Archipelago, Russian novelist and historian Alexandr Solzhenitsyn states that Richard Ohola, a Finnish Red Guard, was "a participant in the capture of British agent Sidney Reilly".[151] In the biographical glossary appended to the latter work, Solzhenitsyn incorrectly speculates that Reilly was "killed while crossing the Soviet-Finnish border."[151])

After Reilly crossed the Finnish border, the Soviets captured, transported and interrogated him at Lubyanka Prison.[citation needed] On arrival Reilly was taken to the office of Roman Pilar, a Soviet official who had arrested and ordered the execution of a close friend of Reilly, Boris Savinkov, the previous year; Reilly was reminded of his own death sentence by a 1918 Soviet tribunal for participation in a counter-revolutionary plot against the Bolshevik government.[citation needed] While Reilly was being interrogated, the Soviets publicly claimed that he had been shot trying to cross the Finnish border.[citation needed] Whether Reilly was tortured while in OGPU custody is a matter of debate by historians;[who?] Cook contends that Reilly was not tortured other than psychologically, through mock executions designed to shake the resolve of prisoners.[citation needed]

During OGPU interrogation Reilly prevaricated about his personal background and maintained his charade of being a British subject born in Clonmel, Ireland. Although he did not abjure his allegiance to the United Kingdom, he also did not reveal any intelligence matters.[152] While facing such daily interrogation, Reilly kept a diary in his cell of tiny handwritten notes on cigarette papers which he hid in the plasterwork of a cell wall. While his Soviet captors were interrogating Reilly he in turn was analysing and documenting their techniques. The diary was a detailed record of OGPU interrogation techniques, and Reilly was understandably confident that such unique documentation would, if he escaped, be of interest to the British SIS. After Reilly's death, Soviet guards discovered the diary in Reilly's cell, and photographic enhancements were made by OGPU technicians.[153]

Reilly was executed in a forest near Moscow on Thursday, 5 November 1925.[154] Eyewitness Boris Gudz claimed the execution was supervised by an OGPU officer, Grigory Feduleev, while another OGPU officer, Grigory Syroezhkin, fired the final shot into Reilly's chest. Gudz also confirmed that the order to kill Reilly came from Stalin directly. Within months after his execution, various outlets of the British and American press carried an obituary notice: "REILLY—On the 28th of September, killed near the village of Allekul, Russia, by S. R. U. Troops. Captain Sidney George Reilly, M. C., beloved husband of Pepita Reilly."[137] Two months later, on 17 January 1926, The New York Times reprinted this obituary notice and, citing unnamed sources in the intelligence community, the paper asserted that Reilly had been somehow involved in the still ongoing scandal of the Zinoviev Letter,[6] a fraudulent document published by the British Daily Mail newspaper a year prior during the general election in 1924.[139]

After Reilly's death there were various rumours about his survival;[clarification needed] Reilly's wife Pepita Bobadilla claimed to possess evidence indicating that Reilly was still alive as late as 1932.[9][15] Others speculated that the unscrupulous Reilly had defected to the opposition, becoming an adviser to Soviet intelligence.[12][155][f] Despite such unfavourable rumours the international press quickly turned Reilly into a household name, lauding him as a masterful spy and chronicling his many espionage adventures with numerous embellishments. Contemporary newspapers dubbed him "the greatest spy in history" and "the Scarlet Pimpernel of Red Russia".[15] In May 1931, The London Evening Standard published an illustrated serial headlined "Master Spy" which sensationalised his many exploits as well as outright invented others.[citation needed]

Fictional portrayals

Soviet cinema

As one of the principal suspects in the Ambassador's Plot and a key figure in the counter-revolutionary activities of White Russian émigrés, Reilly accordingly became a recurring villain in Soviet cinema. In the latter half of the 20th century, he frequently appeared as a historical character in films and television shows produced by the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries. He was portrayed by many different actors of various nationalities including: Vadim Medvedev in The Conspiracy of Ambassadors (Zagovor Poslov) (1966); Vsevolod Yakut in Operation Trust (Operatsiya Trest) (1968); Aleksandr Shirvindt in Crash (Krakh) (1969); Vladimir Tatosov in Trust (1976), Sergei Yursky in Coasts in the Mist (Mglistye Berega) (1986), and Harijs Liepins in Syndicate II (Sindikat-2) (1981).

Reilly: Ace of Spies

In 1983, a television miniseries, Reilly, Ace of Spies, dramatised the historical adventures of Reilly. Directed by Martin Campbell and Jim Goddard, the programme won the 1984 BAFTA TV Award. Reilly was portrayed by actor Sam Neill who was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for his performance. Leo McKern portrayed Sir Basil Zaharoff. The series was based on Robin Bruce Lockhart's book, Ace of Spies, which was adapted by Troy Kennedy Martin.

In a review of the programme, Michael Billington of The New York Times noted that "pinning Reilly down in 12 hours of television is difficult precisely because he was such an enigma: an alleged radical, yet one who helped to bring down Britain's first Labour government in 1924 by means of a forged letter, supposedly from the Bolshevik leader Grigory Zinoviev, instructing the British Communists to form cells in the armed forces; a Lothario and two-time bigamist who was yet never betrayed by any of the women he was involved with; an avid collector of Napoleona who wanted to be the power behind the throne rather than to rule himself."[15]

James Bond

In Ian Fleming, The Man Behind James Bond by Andrew Lycett, Sidney Reilly is listed as an inspiration for James Bond.[16] Reilly's friend, former diplomat and journalist Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, was a close acquaintance of Ian Fleming for many years and recounted to Fleming many of Reilly's espionage adventures.[157] Lockhart had worked with Reilly in Russia in 1918, where they became embroiled in an SIS-backed plot to overthrow Lenin's Bolshevik government.[73]

Within five years of his disappearance in Soviet Russia in 1925, the press had turned Reilly into a household name, lauding him as a master spy and recounting his many espionage adventures. Fleming had therefore long been aware of Reilly's mythical reputation and had listened to Lockhart's recollections. Like Fleming's fictional creation, Reilly was multi-lingual, fascinated by the Far East, fond of fine living, and a compulsive gambler.[157] When queried on whether Reilly's colourful life had directly inspired Bond, Ian Fleming replied: "James Bond is just a piece of nonsense I dreamed up. He's not a Sidney Reilly, you know."[15]

The Gadfly

In 1895, Reilly encountered author Ethel Lilian Voynich, née Boole.[28] Boole was a well-known figure in the late Victorian literary scene and later married to Polish revolutionary Wilfrid Voynich. She and Reilly had a sexual liaison in Italy together.[28] During their affair, Reilly supposedly "bared his soul" to Ethel and revealed to her the peculiar story of his revolutionary past in the Russian Empire. After their affair had concluded, Voynich published in 1897 The Gadfly, a critically acclaimed novel whose central character is allegedly based on Reilly's early life.[36] Alternatively, Reilly modelled himself on the hero of Voynich's novel, Giuseppe Mazzini, although historian Mark Mazower observed "separating fact from fantasy in the case of Reilly is difficult".[158] For years, the existence of this purported relationship was doubted by sceptical historians until confirmed by new evidence in 2016.[28] Archived communication between Anne Fremantle—who attempted a biography of Ethel Voynich—and a relative of Ethel's on the Hinton side demonstrates that a liaison did occur.[28] The theme music for the 1983 television mini-series is essentially a piece of The Gadfly Suite (Op. 97a) by Dmitri Shostakovich.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Reilly's birth year is disputed. He listed 1873 as his birth year in all documents prior to 1917,[21] after which he listed 1874.[21] In the Evening Standard serialization of Reilly's life, his wife Pepita Bobadilla speculated that he was born in 1872,[21] but she revised this to 1874 in her memoir.[22] R. H. Bruce Lockhart believed that he was born in 1873,[23] while the Soviet OGPU posited 1874.[20]

- ^ Switching one's political allegiances from anti-Tsarist revolutionary activist to pro-Tsarist police informant as a result of Okhrana blackmail was quite frequent in the final decade of the Russian Empire.[29] For examples of Okhrana informants similar to Sidney Reilly and Alexander Grammatikov, see R. C. Elwood, Russian Social Democracy in the Underground: A Study of the RSDRP in the Ukraine, 1907–1914 (Assen, 1974), pp. 51–58.

- ^ a b Winfried Lüdecke's 1929 mini-biography of Reilly was criticized as highly erroneous by Pepita Bobadilla, Reilly's last wife. Bobadilla wrote in 1931: "The section devoted to [Reilly] in Winfried Ludecke's standard work Behind the Scenes of Espionage abounds in inaccuracies." See Bobadilla's foreword to Adventures of a British Master Spy.[22]

- ^ William Melville is inaccurately described by writer Andrew Cook as the first director general of MI5.[56] In contrast, MI5's authorized biographer Christopher Andrew describes Melville as the informal chief of a separate Special Section of the British Secret Service Bureau,[40] the antiquated forerunner to the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS).[11]

- ^ Confusion exists regarding whom Reilly initially contacted upon his April 1918 arrival in Moscow.[85] Pepita Bobadilla's 1931 book claims that Reilly saw General Mikhail Bonch-Bruyevich. However, General Bonch-Bruyevich's memoirs state that—while his old acquaintance Reilly had spoken with him in Petrograd during Spring 1918—Reilly "never came to see me in Moscow".[86] Edward Van Der Rhoer posits that Reilly instead contacted Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich, Vladimir Lenin's friend and secretary of the Council of People's Commissars.[84]

- ^ a b The persistent myth that Sidney Reilly was a Soviet agent originates in speculative remarks made at Oslo on 30 September 1918 by Dewitt C. Poole, the former U.S. Consul-General in Russia.[12] Both R. H. Bruce Lockhart and George Hill later rejected Poole's remarks as risible. Their confidence in Reilly's anti-Bolshevism was confirmed in 1992 following access to OGPU interrogation reports preceding Reilly's execution.[156]

- ^ a b In 1993, Russia's Security Ministry raised doubts about the participation of Fanya Kaplan in the 30 August 1918 assassination attempt on Vladimir Lenin. See UPI press release in the Bibliography section.[117]

- ^ In 1938, Reilly's resolute prosecutor Nikolai Krylenko was ultimately arrested himself during Joseph Stalin's Great Purge.[129] Following interrogation and torture by the NKVD, Krylenko confessed to extensive involvement in anti-Soviet agitation. After a twenty-minute trial, Krylenko was sentenced to death by the Military Collegium of the Soviet Supreme Court and executed immediately afterwards.[129] In Memoirs of a British Agent (1932), R. H. Bruce Lockhart described Krylenko as "an epileptic degenerate ... and the most repulsive type I came across in all my connections with the Bolsheviks".[130]

- ^ The announcement that Sidney Reilly had been awarded the Military Cross (MC) was published in The London Gazette on 11/12 February 1919: "His Majesty the KING (George V) has been graciously pleased to approve the undermentioned rewards for distinguished services rendered in connection with Military operations in the Field:—Awarded the Military Cross. Lieutenant. George Alexander Hill, 4th Bn; Manch. R.; attend. R.A.F., 2nd Lt. Sidney George Reilly, R.A.F." See "No. 31176". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 11 February 1919. p. 2238. This citation misled biographers such as Richard Deacon to conclude that Reilly's medal was bestowed for military feats against the Imperial German Army during the World War I.[72]

Citations

- ^ a b c Deacon 1987, pp. 133–136.

- ^ a b c Deacon 1987, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Deacon 1972, pp. 144, 175.

- ^ a b c McNeal 2002, p. 137.

- ^ a b c Spence 2002, pp. 57–59.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Williamson 1926.

- ^ a b c Ludecke 1929, p. 107.

- ^ a b Hill 1932, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n New York Times 1933.

- ^ a b c d e Thomson 2011.

- ^ a b c d e SIS Website 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lockhart 1932, pp. 277, 322–323.

- ^ Spence 2002, Chapter 8: The Russian Question.

- ^ Lockhart 1932.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Billington 1984.

- ^ a b Lycett 1996, pp. 118, 132.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrew 1986, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d Deacon 1987, p. 134.

- ^ a b Ludecke 1929, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Spence 2002, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Cook 2002, pp. 24, 292.

- ^ a b c d e f Bobadilla & Reilly 1931, Foreword.

- ^ a b c d e f Lockhart 1932, p. 322.

- ^ Segodnya 2007.

- ^ a b Lockhart 1986

- ^ a b c Cook 2004, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Ainsworth 1998, p. 1447.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy 2016, pp. 274–276.

- ^ a b c d e Elwood 1986, p. 310.

- ^ a b c Lockhart 1967, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Cook 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Cook 2004, p. 56.

- ^ a b Lockhart 1967, p. 27.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2016, pp. 274–76.

- ^ a b c Ramm 2017.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, p. 39.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, p. 44.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, p. 34.

- ^ a b Andrew 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Spence 2002, pp. 28–39.

- ^ Lockhart 1967, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Cook 2004, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, pp. 15–18.

- ^ a b Spence 1995, p. 92.

- ^ Nish 2014.

- ^ Cook 2004, pp. 44–50.

- ^ a b c d Castravelli 2006, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f Ludecke 1929, p. 106.

- ^ Spence 2002, pp. 40–55.

- ^ Cook 2004, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Cook 2002, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Spence 2002, pp. 56–59.

- ^ a b Andrew 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b Yergin 1991, p. 140.

- ^ a b Lockhart 1967, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Cook 2004, p. 78.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, pp. 64–68.

- ^ a b c d Lockhart 1967, p. 47.

- ^ a b Spence 2002, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Lockhart 1967, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Lockhart 1967, p. 36.

- ^ Cook 2004, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Van Der Rhoer 1981, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Spence 2002, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Cook 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Lockhart 1967, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Deacon 1987, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Andrew 1986, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d e Long 1995, p. 1228.

- ^ Spence 2002, Chapter 6: War on the Manhattan Front.

- ^ Andrew 1986.

- ^ a b c d e Hicks 1920.

- ^ a b Spence 2002, pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b Spence 2002, pp. 172–173, 185–186.

- ^ "No. 30497". The London Gazette (Supplement). 25 January 1918. p. 1363.

- ^ a b c d McNeal 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Bonch-Bruyevich 1966, p. 303.

- ^ a b Spence 2002, p. 195.

- ^ a b Van Der Rhoer 1981, p. 2.

- ^ a b Elwood 1986, p. 311.

- ^ Bonch-Bruyevich 1966, p. 265.

- ^ Milton 2014, p. 112.

- ^ Van Der Rhoer 1981, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Elwood 1986, pp. 310–311.

- ^ McNeal 2018.

- ^ a b Spence 2002, pp. 187–191.

- ^ McNeal 2002, p. 121.

- ^ Hill 1932, pp. 241–242.

- ^ a b c d e f Long 1995, p. 1225.

- ^ a b Long 1995, p. 1226.

- ^ Debo 1971.

- ^ a b c d Long 1995, p. 1227.

- ^ Hill 1932, pp. 237–238.

- ^ McNeal 2002, pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b McNeal 2002, p. 234.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, pp. 162–164.

- ^ a b Long 1995, p. 1230.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ferguson 2010, pp. 1–5, Prologue.

- ^ Hill 1932, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e Cook 2004, pp. 166–169.

- ^ a b Long 1995, p. 1229.

- ^ a b c Long 1995, p. 1231.

- ^ Ainsworth 1998, p. 1448.

- ^ Kitchen: "Hill, George Alexander (1892–1968). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography."

- ^ a b Hill 1932, p. 239.

- ^ a b c d e Lockhart 1932, pp. 317–318.

- ^ a b c d Brooklyn Eagle 1918.

- ^ a b c Washington Post 1918.

- ^ a b Brooke 2006, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Donaldson & Donaldson 1980, p. 221.

- ^ Volkogonov 1994, pp. 222, 231.

- ^ Gransden 1993.

- ^ a b Brooke 2006, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d New York Times 1918, pp. 1, 6.

- ^ Britnieva 1934, pp. 77–86.

- ^ a b Lockhart 1932, p. 320.

- ^ Lockhart 1932, p. 330.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 209.

- ^ Hill 1932, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 234.

- ^ a b c d e Hill 1932, pp. 244–245.

- ^ a b Spence 2002, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d e Service 2012, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b c Feofanov & Barry 1995, pp. 3, 5, 10–12.

- ^ Lockhart 1932, p. 257.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 236.

- ^ Spence 2002, p. 453.

- ^ Ainsworth 1998, p. 1454.

- ^ Spence 2002, pp. 247–251.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 1998, pp. 1447–1470.

- ^ a b Lockhart 1967, p. 111.

- ^ a b New York Times 1925.

- ^ Bobadilla & Reilly 1931, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d e f Kettle 1986, p. 121.

- ^ Madeira 2014, p. 124.

- ^ a b Corry 1984.

- ^ Cook 2004, p. 188.

- ^ "No. 31176". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 February 1919. p. 2238.

- ^ Andrew 1986, pp. 433, 448.

- ^ a b c Elwood 1986, p. 312.

- ^ Deacon 1987, p. 136.

- ^ Grant 1986, pp. 51–77.

- ^ Cook 2004, p. 238.

- ^ Ristolainen 2009.

- ^ Kotakallio 2016, p. 142.

- ^ a b Solzhenitsyn 1974, pp. 127, 631.

- ^ Spence 2002, pp. 455–456.

- ^ Cook 2004, p. 250.

- ^ Cook 2004, pp. 258–259.

- ^ Van Der Rhoer 1981, pp. 186–235.

- ^ Ainsworth 1998, p. 1466.

- ^ a b Cook 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Mazower 2018, pp. 31–33.

Bibliography

Print sources

- Ainsworth, John (1998). "Sidney Reilly's Reports from South Russia, December 1918 – March 1919" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 50 (8): 1447–1470. doi:10.1080/09668139808412605.

- Andrew, Christopher (2009). Defend the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5. New York: Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0713998856.

- Andrew, Christopher (1986) [1985]. Her Majesty's Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community. Viking. ISBN 978-0-6708-0941-7.

- Bobadilla, Pepita; Reilly, Sidney (1931). Britain's Master Spy: The Adventures of Sidney Reilly. London: Elkin Mathews & Marrot. ISBN 978-0-88184-230-2.

- Britnieva, Mary (1934). One Woman's Story. London: Arthur Baker Limited. pp. 77–86. ASIN B000860RP4.

- Brooke, Caroline (2006). Moscow: A Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1953-0952-2.

- Bonch-Bruyevich, Mikhail Dmitriyevich (1966). From Tsarist General to Red Army Commander. Translated by Vladimir Vezey. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 257, 263, 265, 303.

- Cook, Andrew (2002). On His Majesty's Secret Service, Sydney Reilly Codename ST1. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2555-9. (2nd edition published as: Cook, Andrew (2004). Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-6953-9.)

- Deacon, Richard (1987). Spyclopedia: The Comprehensive Handbook of Espionage. London: MacDonald. ISBN 978-0-3561-4600-3.

- Deacon, Richard (1972). A History of the Russian Secret Service. Taplinger Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-8008-3868-3.

- Debo, Richard K. (3 September 1971). "Lockhart Plot or Dzerhinskii Plot?". The Journal of Modern History. 43 (3): 413–439. doi:10.1086/240650. JSTOR 1878562. S2CID 144258437.

- Donaldson, Norman; Donaldson, Betty (1980). How Did They Die?. Vol. Volume One. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3123-9488-2.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Ferguson, Harry (2010). Operation Kronstadt: The True Story of Honour, Espionage, and the Rescue of Britain's Greatest Spy The Man with a Hundred Faces. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-0995-1465-7.

Captain Francis Cromie of the British Naval Intelligence Department (NID) was the de facto chief of all British intelligence operations in northern Russia.

- Grant, Natalie (Winter 1986). "Deception on a Grand Scale". International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. 1 (4): 51–77. doi:10.1080/08850608608435036.

- Grant, Natalie (Winter 1991). "The Trust". American Intelligence Journal. 12 (1): 11–15. JSTOR 44319063.

- Hicks, W.W. (2 November 1920). Memorandum on British Secret Service Activities in This Country (PDF) (Report). National Archives and Record Service (NARS). pp. 1–3. Doc. 9771-745-45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Hill, George Alexander (1932). Go Spy the Land. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-8495-4708-6.