Larvik

Larvik Municipality

Larvik kommune | |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): Bakkebyen, The Hilly City | |

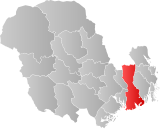

Vestfold og Telemark within Norway | |

Larvik within Vestfold og Telemark | |

| Coordinates: 59°4′52″N 10°0′59″E / 59.08111°N 10.01639°E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Vestfold og Telemark |

| District | Vestfold |

| Administrative centre | Larvik |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2019) | Erik Bringedal (H) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 535 km2 (207 sq mi) |

| • Land | 501 km2 (193 sq mi) |

| • Rank | #199 in Norway |

| Population (2017-1-1) | |

| • Total | 46,211 |

| • Rank | #19 in Norway |

| • Density | 82/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | |

| Demonym(s) | Larviking Larviker Larvikar[1] |

| Official language | |

| • Norwegian form | Neutral |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-3805[3] |

| Website | Official website |

Larvik (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈlɑ̂rviːk] )[4] is a town and municipality in Vestfold in Vestfold og Telemark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Larvik. The municipality of Larvik has about 46,364 inhabitants. The municipality has a 110 km coastline, only shorter than that of neighbouring Sandefjord.[5]

The city achieved market town status in 1671.[6] Larvik was established as a municipality on 1 January 1838 (see formannskapsdistrikt). The city of Stavern, and the rural municipalities of Brunlanes, Hedrum, and Tjølling were forcefully merged into the municipality of Larvik on 1 January 1988.[7] On 1 January 2018, neighboring Lardal was merged into Larvik as part of a nationwide municipal reform.[8] After the merge, Larvik is the largest municipality in Vestfold by area, and the second-most populous municipality in the Vestfold district.[9]

Larvik is known as the hometown of Thor Heyerdahl.[10] It is also home to Bøkeskogen, the northernmost beech tree forest in the world. It is also home of Norway's only natural mineral water spring, Farriskilden.[11][12] Farris Bad has been described as one of the best spas in Europe.[13] It has the largest spa department in Scandinavia.[14][15]

Larvik has a daily ferry connection to Hirtshals, Denmark.[16]

Etymology

The Norse form of the name must have been Lagarvík. The first element is the genitive case of lǫgr m 'water; river' (now called Numedalslågen River). The second element is vík f 'cove, wick'. The meaning of the name is "the cove at the mouth of (Numedals)lågen". Prior to 1889, the name was written "Laurvik" or "Laurvig".

Coat of arms

The coat of arms is from only 2017. It is blue, with silver drops to represent waterways, harbour and growth for which the municipality is known.

History

Various remains from the Stone Age have been discovered in Larvik, for instance by Torpevannet by Helgeroa village. Raet goes through all of Vestfold County before peaking out of the ocean in Mølen. Ancient peoples have carried rocks from Raet and constructed vast numbers of burial mounds at Mølen. During the Roman Iron Age, ancient peoples erected a stone monument resembling a ship at Istrehågan, one of Norway's greatest remains ("oldtidsminne") from prehistoric times.[18] Immediately across the Sandefjord border by Istrehågan is Haugen farm, which is the largest petroglyph site in Vestfold County.[19]

Kaupang in Skiringssal is an archaeological site where archaeologists first discovered burial mounds, and later uncovered the remains of an ancient town. It is now known as the oldest known merchant town in Norway. There was international trade from a bay in Viksfjord, a few kilometres east of Larvik, over 1,200 years ago.[20] Skiringssal has remains from the oldest town yet discovered in the Nordic Countries,[21] and it was one of Scandinavia's earliest urban sites.[22]

Larvik was a Danish county (grevskap) until 1817; the rest of Norway had come under Swedish rule in 1814; four local businessmen purchased the county (in 1817).[23]

The city of Larvik was a 19th-century spa community, home of Larvik Bath. The spa welcomed several members of government and also Russian oligarchs. The royal family, King Haakon VII and Queen Maud, vacationed at Larvik Bad in 1906. The spa also welcomed Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson in 1909, who wrote some of his lasts poems in Larvik, and Knut Hamsun in 1917. Hamsun wrote his novel Growth of the Soil in Larvik, which later earned him the 1920 Nobel Prize for Literature.[24]

Larvik received market town status in 1671.[25] The city of Larvik (in contemporaneous Danish spelling: Laurvig) was founded in 1671 by Ulrik Fredrik Gyldenløve, who became the first count of Laurvig. The count's residence, "Herregården", can still be visited today. Larvik houses the Treschow estate, Fritzøehus, which is currently owned by the heirs of Mille-Marie Treschow, reportedly "Norway's richest woman". The Treschow estate was created in 1835 when Willum Frederik Treschow bought the county from the Danish crown, who in turn had bought the county from the local consortium "grevlingene", four local entrepreneurs who proved unable to manage the ownership financially (the consortium had bought the county from the Danish crown in 1817 originally, the crown taking over the county when the last of the counts had to sell it because of debt).

Larvik, along with neighbouring Sandefjord and Tønsberg, were the three dominant whaling cities of Norway in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[26]

Demographics

Larvik's population is primarily centred around the coast. The administrative centre of the municipality, Larvik proper, is one of two cities in the municipality; the other one being Stavern. The city's residential areas are first and foremost in the hills between the fjord and Bøkeskogen.[27]

| Ancestry | Number |

|---|---|

| 1,095 | |

| 412 | |

| 391 | |

| 388 | |

| 333 | |

| 297 | |

| 216 | |

| 211 | |

| 203 | |

| 196 | |

| 139 | |

| 127 | |

| 119 | |

| 116 | |

| 113 | |

| 1 |

The municipality had a total population of 46,899 as of January 1, 2018,[29] while the city of Larvik had a population of 23,927 as of 2016.[30] Immigrants made up 11.2 percent of the population in 2017.[31] The largest immigrant groups (first- and second generation immigrants) were: Polish (1,200), Lithuanians (446), Iraqis (408), Vietnamese (327), and Somalis (318).[32]

Figures from a census held at the beginning of the 19th century indicate that Larvik's population has quadrupled in approximately 200 years. Its population however is spread through the county's largest municipality, and less than 50% reside in the city of Larvik. The majority of the population is found along and around the Larviksfjord, from Stavern in the west to Gon in the east.[33] The population sometimes double during summer weeks due to tourism.[34] Larvik is home to 4,775 vacation homes as of 2018.[35]

Economy

Larvik is the most important agricultural municipality in Vestfold. Besides grains, other crops include potatoes and vegetables. It has the county's largest production of cucumbers and tomatoes. Important industries are commerce, hotel and restaurant management. The fishing industry is the second-largest in Vestfold, only smaller than in Færder. Important fishing harbours are Stavern, Helgeroa, and Nevlunghavn. Furthermore, Larvik has the biggest logging industry in the county. Norway Spruce is the most important tree species.[36]

Larvikite is exported from Larvik to countries in Europe and to the United States.[37]

Tourism

Larvik is first and foremost known as a summer community. Due to its stable climate and one of Norway's highest median temperatures, Larvik experiences significant summer tourism.[38][39] Larvik's climate is among the mildest in Norway, with one of the nation's highest number of annual sunshine days. It is home to over 4,000 holiday homes.[40]

The coastal town of Stavern and picturesque villages of Helgeroa and Nevlunghavn receive large numbers of tourists during summer months. Stavern is known as a summer community,[41] and its population more than doubles during summers.[42] Tourist attractions in Stavern include Hall of Remembrance, Fredriksvern, and Citadellet. Citadel Island is home of Staverns Fortress which dates to the 1680s. The island is a current refuge for artists.[43][44]

Kaupang has been described as the "chief attraction" for visitors in Larvik.[45] Kapuang is also known as Norway's most important monument from the Viking Age.[46] Another source describes Mølen Geopark as Larvik's most visited tourist attraction.[47] Other attractions include the Maritime Museum, Fritzøehus, Herregården, the home of Thor Heyerdahl, and Bøkeskogen. Larvik is also home to Farris Bad, the largest spa in the Nordic countries, which has been described as one of Europe's best spa facilities.[48]

Geography

Larvik occupies the southwestern corner of Vestfold, between Sandefjord in the east and the Langesundsfjord in the west. The coast stretches from the entrance to the Sandefjordsfjord and to the Langesundsfjord. The coastline consists of various beaches, bays, islets and skerries. The land is relatively flat along the coast and by the many bays, while the interior parts consist of large and hilly woodlands. Larger mountains are found along the border to Telemark County in the west.[52] Berganvarden at 456 metres is the highest peak in Larvik municipality. It lies in northwestern Larvik, on the west side of Lågen River. The peak is situated at the border with Lardal and Siljan.[53]

The municipality is approximately 105 kilometres (65 mi) southwest of Oslo. The municipality covers an area of 530 square kilometres (200 sq mi), and has a population of 41,211 (23,100 of which reside in the town). Larvik is the largest municipality in Vestfold County with an area covering 531 km2. However, by population Larvik is the third-most populous municipality, only smaller than neighbouring Tønsberg and Sandefjord.[54] Larvik has its own fjord which connects to the Lågen River.[55]

Larvik borders to Kongsberg in the north, Sandefjord in the east, and Porsgrunn and Siljan (Telemark County) in the west. The southernmost point in the municipality is Tvistein Lighthouse in the sea south of Hummerbakken in Brunlanes. On the mainland, its southernmost point is found in Oddane, between Mølen and Nevlunghavn. The westernmost point is Geiterøya Island in the Langesundsfjord, and the easternmost point is one of the Rauer islets. The highest point is Vindfjell at 622 m. which lies on the border with Telemark County in the west.[56]

The district also includes the town of Stavern (population: 5,000) and the villages of Nevlunghavn, Helgeroa, Kvelde, Hvarnes, and Tjølling. Notable geographical features include the lake Farris and the river Numedalslågen, locally called Lågen, which terminates in Larvik, east of the town. Other bodies of water include the lakes Farris, Goksjø and Hallevatnet.

Larvik is also noted for its natural springs of mineral water, Farriskildene, which have been commercially exploited under the brand name Farris. At Kaupang in Tjølling lies the remains of the medieval Skiringssal trading outpost. Larvik is also home to the world's northernmost natural occurrence of Fagus sylvatica forests (European Beech tree), known as Bøkeskogen ("The Beech Tree Forest").

Villages

The municipality is home to one city and seven villages:[58]

- Larvik (23,927)

- Stavern (5,635)

- Helgeroa and Nevlunghavn (1,890)

- Lauve/Viksfjord (1,777)

- Kvelde (931)

- Verningen (931)

- Svarstad (608)

Himberg is an exclave which is part of Sandefjord, although bordering Larvik in all directions.[59][60][61] Attempts at annexing Himberg into Larvik have largely been met with protests from Himberg residents. A 1995 attempt at annexing Himberg was cancelled due to protests from local residents.[62] There are only four such enclaves in Norway, and Himberg is the most populous enclave in Norway, with a population of approximately 40 people. Himberg is 1.4 km2 (0.54 sq. mi.).[63]

Culture

Larvik Museum

Larvik Museum Society founded in 1916. The museum is now associated with Vestfold Museum (Vestfoldmuseene). Larvik Museum was established with the purpose of preserving, and restoring the city's collection of historic buildings. [64][65][66]

Treschow-Fritzøe Museum (Verkensgården) houses exhibitions from the former Treschow-Fritzøe ironworks. Verkensgarorden displays tools, equipment, drawings, and models illustrating the iron-production era in Larvik, which dated from 1670 to 1870. The exhibition shows various aspects; from the geological process of creation to production, and use of the stone larvikite, the area's main export product. The Iron Works was closed during 1868.[68]

Manor House (Herregården) was built by Ulrik Fredrik Gyldenløve for his third wedding in 1677. It is a large wooden structure with well-preserved baroque interiors from the 1730s. Herregården manor house is a large Baroque wooden building with classic elements. The interior design is mainly Baroque and Regency style. The house is filled with 17th- and 18th-century antiques.[73] Herregården from 1677 is considered one of Norway's finest secular Baroque structures.[74] It is one of few baroque architectural monuments representing nobility in Norway.[75][76] Furthermore, it is one of Norway's largest wooden buildings from 17th century.[77]

Larvik Maritime Museum (Larvik Sjøfartsmuseum) is housed in Larvik's oldest brick building, dating from 1730. Larvik Maritime Museum is located in the old customs house, and is the residence of the local building inspector. This museum displays models of ships, paintings of sailing vessels, and other nautical artifacts to bring the port's maritime history alive. One section of the museum is devoted to the expeditions of Larvik-born Thor Heyerdahl.[78][79]

Fritzøehus

Fritzøehus is a private estate located in Larvik. The estate has traditionally been associated with various members of the Treschow family and is presently owned by Mille-Marie Treschow.

It is Norway's largest privately owned estate.[80][81][82]

Recreation areas

Recreation areas include the beach Lydhusstranda at Naverfjorden.[83]

Numedalslågen, which is considered one of Norway's best salmon fishing rivers, is located in Larvik.[84][85][86][87] Freshwater fishing is also common at Goksjø Lake, which lies on the Sandefjord-Larvik border. Fish species in this lake include Northern pike, European perch, Ide, Common dace, European eel, Salmon, and Brown trout.[88] The lake is also used for ice-skating, canoeing, swimming, boating, and other recreational activities.

The 12-metre Trollfoss is the largest and tallest waterfall in Vestfold County.[89][90][91][92]

Hiking trails can be found throughout the municipality, including in the city forest Bøkeskogen, Norway's largest beech tree forest.[93][94] This forest is home to various trails, from 2.6 km (1.6 mi.) to the longest which is 10 km (6.2 mi.) in length.[95] Hiking trails can also be found at Mølen, which is an UNESCO GeoPark and home of Norway's largest stone beach.[96][97] The Coastal Path (Kyststien) is a 35 km from Brunlanes to Stavern. Additional hiking trails can be found by Goksjø- and Farris Lakes.[98] Farris Lake is the largest lake in Vestfold County.[99]

Due to the municipality's many rural areas, Larvik is known for its game hunting, and large forests are open for hunting. There are great stocks of moose; Larvik has among Norway's highest number of moose.[100] Between 7-800 moose are annually slaughtered in the county.[101] Other important species of game are Roe deer, Red deer, Mountain hare, European beaver, and Common wood pigeon.[102]

Beaches

List of publicly owned beaches in Larvik:[103]

- Farris

- Rekkeviksbukta

- Batteritomta

- Gonstranda (Østre Halsen)

- Hvittensand (Østre Halsen)

- Corntin (Stavern)

- Blokkebukta (Naverfjord)

- Anvikstranda (Naverfjord)

- Stolpstadstranda (Naverfjord)

- Lydhusstranda (Naverfjord)

- Roppestad (Farris)

- Skjærsjø (Kvelde)

- Ula (Tjølling)

- Kjerringvik (Tjølling)

Transportation

Larvik is served by Sandefjord Airport Torp, its nearest international airport.[104] European route E18 traverses the municipality and is one of Norway's most important main highways.[105] Larvik Station is the city's main railway station, while daily ferries to Hirtshals, Denmark depart from the city harbour and are operated by Color Line.[106] The neighbouring city of Sandefjord has several ferry links with daily departures to Strömstad, Sweden and, further south, the city of Langesund links to Hirtshals, Denmark through a ferry which is operated by Fjord Line.

Points of interest

Notable points of interest include:[109]

- Istrehågan, ancient burial ground on the Larvik-Sandefjord border

- Bøkeskogen, Norway's largest and the world's northernmost beech tree forest.[110][111]

- Larvik Maritime Museum, museum dedicated to Larvik's nautical history. It is home to several models by Colin Archer, and has its own exhibition dedicated to Thor Heyerdahl.[112]

- Helgeroa and Nevlunghavn, adjacent coastal villages

- Kaupang in Skiringssal, remains from the oldest Nordic town yet discovered.[113]

- Mølen, first UNESCO Global Geopark in the Nordic Countries. It is home to 230 cairns dating to the Iron Age.[114]

- Farris Lake, largest lake in Vestfold County.[115][116]

- Stavern, coastal village and former home of Norway's main naval base in Fredriksvern

- Hall of Remembrance, largest monument in Vestfold County.[117]

- Citadel Island, fort which came to prominence during the Nordic War of 1709–1720.[118]

- Farris Bad, built next to Larvik's best sandy beach, Farris Bad is named amongst the best spas in Europe by Lonely Planet Publications.[119]

- The Nesjar Monument, located in Helgeroa, made on the 1,000th anniversary for the Battle of Nesjar. First unveiled July 29, 2016.

- Herregården, erected in 1677 and recognised as one of Norway's finest secular Baroque structures.[120]

- Larvik Church, erected in 1877 and situated at Tollerodden. Famous for its paintings.[121]

- Childhood home of Thor Heyerdahl, located at Steingata 7 in Larvik proper.

- Goksjø, third-largest lake in Vestfold County, located on the Sandefjord-Larvik border. Used for swimming, fishing, kayaking, ice-skating, and skiing.

Gallery

-

Burial mound in Bøkeskogen.

-

Fredriksvern in Stavern.

-

Former Larvik Town Hall.

-

Widerøe aerial photo, 1964.

-

Larvik City Centre.

-

Mølen is Norway's longest stone beach.

Notable residents

Honorary citizens

- Thor Heyerdahl (1914–2002) a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer

- Carl Nesjar (1920–2015) a painter, sculptor and graphic artist; worked with Pablo Picasso

- Antonio Bibalo (1922–2008) an Italian-Norwegian pianist; composed classical operas

- Arne Nordheim (1931–2010) a Norwegian composer

- Ingvar Ambjørnsen (born 1956) a Norwegian writer [125]

Explorers

- Johan Bryde (1858–1925) a Norwegian ship owner and whaler

- Carl Anton Larsen (1860–1924) a Norwegian Antarctic explorer, discovered fossils

- Oscar Wisting (1871–1936) a Norwegian Naval officer and polar explorer

- Erik Hesselberg (1914-1972) Kon-Tiki crew member, author, painter and sculptor

- Thorstein Baarnes (born 1984), explorer, hunter, philanthropist and inventor

- Jarle Andhøy (born 1977) a controversial Norwegian adventurer and sailing skipper

Public Service & public thinking

- Jens Schou Fabricius (1758–1841) Vice-admiral & Norwegian Minister of the Navy 1817–1818

- Friderich Adolph von Schleppegrell (1792–1850) was a Dano-Norwegian military officer.

- Johan Sverdrup (1816–1892), politician, Prime Minister of Norway 1884-1889

- Thomas Archer (1823-1905), Australian pastoralist and Agent General for Queensland

- Colin Archer (1832–1921) a Norwegian naval architect and shipbuilder

- Sophus Bugge (1833–1907) a Norwegian philologist and linguist

- Karl Gether Bomhoff (1842–1925) pharmacist, politician and Governor of Norges Bank

- Bertrand Narvesen (1860–1939) a Norwegian businessman, founded Narvesen

- Bernt Berntsen (1863–1933) a Norwegian-American Protestant Christian missionary to China

- Anna Hvoslef (1866–1954) a Norwegian journalist, politician and feminist

- Adolf Fonahn (1873–1940) a Norwegian physician, medical historian and orientalist

- Niels Christian Ditleff (1881–1956) diplomat, architect of White Buses operation

- Erling Utnem (1920–2006) a theologian, priest and Bishop of Agder 1973-1983

- Herman Sachnowitz (1921-1978) one of the few Norwegian Jews who survived deportation to a concentration camp

- Knut Helle (1930–2015) a Norwegian historian and academic

- Mille-Marie Treschow (born 1954–2018) a Norwegian landlord and businessperson

- Lars Gule (born 1955) a Norwegian philosopher and commentator on extremism and terrorism

- Anders Anundsen (born 1975) a Norwegian politician, Minister of Justice 2013-2016

- Hassan Abdi Dhuhulow (1990–2013) a Norwegian-Somalian Islamist terrorist

The Arts

- Hans Holmen (1878–1958) a Norwegian painter and sculptor

- Herman Wildenvey, (1885–1959) prominent Norwegian poet

- Arthur Omre (1887–1967) a Norwegian novelist, liquor smuggler, swindler and thief

- Gunnar Reiss-Andersen (1896–1964) a Norwegian lyric poet and author

- Ruth Lagesen (1914–2005) a Norwegian pianist and conductor

- Carl Nesjar (1920–2015) a painter, sculptor and graphic artist; fabricator for Pablo Picasso

- Arne Nordheim (1931–2010) a Norwegian composer

- Louis Jacoby (born 1942) a Norwegian singer and writer

- Mari Bjørgan (1950–2014) a Norwegian actress and variety show comedian [126]

- Birgitte Einarsen (born in 1975) a Norwegian singer and musical theatre artist from Helgeroa

- Anne Holt (born 1958) a crime writer, lawyer and former Minister of Justice

- Terje Gewelt (born 1960) a Norwegian jazz musician, plays the upright bass, raised in Larvik

- Bjørn Lynne (born 1966) a Norwegian sound engineer and music composer [127]

- Jonas Kilmork Vemøy (born 1986) a Norwegian Jazz trumpeter and composer, raised in Larvik

- Absolute Steel (formed in 1999) a Norwegian heavy metal band

Sport

- Sverre Hansen (1913–1974) footballer, team bronze medallist at the 1936 Summer Olympics

- Gunnar Thoresen (1920-2017) famous footballer, 261 caps for Larvik Turn and 64 for Norway

- Anette Bøe (born 1957) cross-country skier, team bronze medallist at the 1980 Winter Olympics

- Hallvar Thoresen (born 1957) a footballer, with 320 club caps and 50 for Norway

- Tom Erik Oxholm (born 1959) speed skater, twice bronze medallist at the 1980 Winter Olympics

- Tom Sundby (born 1960) a footballer with 39 caps for Norway

- Bjørg Eva Jensen (born 1960) a speed skater and gold medallist at the 1980 Winter Olympics

- Gunnar Halle (born 1965) a football manager and player with 509 club caps and 64 for Norway

- Espen Hoff (born 1981) a Norwegian retired professional footballer with 427 club caps

- Alexander Hvaal (born 1992) a professional rallycross driver

Sports teams

Twin towns – sister cities

Borlänge, Sweden

Borlänge, Sweden Frederikshavn, Denmark

Frederikshavn, Denmark

See also

References

- ^ "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- ^ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ^ Bolstad, Erik; Thorsnæs, Geir, eds. (2023-01-26). "Kommunenummer". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget.

- ^ Berulfsen, Bjarne (1969). Norsk Uttaleordbok (in Norwegian). Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co (W Nygaard). p. 194.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2011). På Tur i Vestfold del 2. E-forlag. Page 238. ISBN 9788293057222.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én: Suksesskriteriene bak nye Sandefjord. E-forl. Page 128. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ "Fra 26 til 6 kommuner". 21 November 2016.

- ^ "Sjekk den nye filmen fra Larvik og Lardal!". 7 December 2017.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 30. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (1998). Bli kjent med Vestfold / Become acquainted with Vestfold. Stavanger Offset AS. Page 65. ISBN 9788290636017.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469.

- ^ Ham, Anthony and Stuart Butler (2015). Lonely Planet Norway. Lonely Planet. Page 91. ISBN 978-1742202075.

- ^ "Farris Bad".

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Pages 17 and 56).

- ^ Doreen, Taylor-Wilkie (2018). Insight Guides Norway. Insight. Page 304. ISBN 978-1780052106.

- ^ "Attractions".

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 8. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Børresen, Svein E. (2004). Vestfoldboka: en reise i kultur og natur. Skagerrak forl. Page 38. ISBN 9788292284070.

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 12. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Doreen, Taylor-Wilkie (2018). Insight Guides Norway. Insight. Page 157. ISBN 978-1780052106.

- ^ Skre, Dagfinn (2007). Kaupang in Skiringssal. Aarhus University Press. Page 13. ISBN 978-8779342590.

- ^ "Unike dokument viser Larviks danske hemmelegheit". 26 June 2021.

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Pages 60-63. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2012). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 125. ISBN 9780756693305.

- ^ Tønnessen, Johan Nicolay and Arne Odd Johnsen (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press. Page 84. ISBN 9780520039735.

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, by immigration category, country background and percentages of the population". ssb.no. Retrieved 23 Sep 2017.

- ^ "Kommunefakta".

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Statistikk".

- ^ "Kommunefakta".

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 32. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 48. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ "Kommunefakta".

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 64. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 97. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 70. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 64. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ "Visit Stavern -Historie".

- ^ Evensberget, Sverre (2016). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465458902.

- ^ Nickel, Phyllis and Hans Jakob Valderhaug (2017). Norwegian Cruising Guide—Vol 2: Sweden, West Coast and Norway, Swedish Border to Bergen. Attainable Adventure Cruising Ltd. Page 98. ISBN 9780995893962.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469.

- ^ Engel, Lyle Kenyon (1963). Scandinavia: A Simon & Schuster Travel Guide. Cornerstone Library. Page 147.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 14. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 67. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Ham, Anthony and Stuart Butler (2015). Lonely Planet Norway. Lonely Planet. Page 91. ISBN 978-1742202075.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (1998). Bli kjent med Vestfold / Become acquainted with Vestfold. Stavanger Offset AS. Page 65. ISBN 9788290636017.

- ^ Ham, Anthony and Stuart Butler (2015). Lonely Planet Norway. Lonely Planet. Page 91. ISBN 978-1742202075.

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 6. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2011). På Tur i Vestfold del 2. E-forlag. Pages 179-182. ISBN 9788293057222.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 32. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Ferguson-Kosinski, Laverne (2015). Europe by Eurail 2016: Touring Europe by Train. Rowman & Littlefield. Page 386. ISBN 9781493012763.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 32. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 67. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et Sted i Sandefjord. Sandar Historielag. Page 139. ISBN 978-82-994567-5-3.

- ^ Larsen, Erlend (2016). Tre kommuner blir til én. Erlend Larsen Forlag. Page 13. ISBN 9788293057277.

- ^ "Sandefjord". 25 March 2021.

- ^ Jøranlid, Marianne (1996). 40 trivelige turer i Sandefjord og omegn. Vett Viten. Pages 114-117. ISBN 9788241202841.

- ^ "Her er Sandefjords ytterste nøgne ø". 11 October 2014.

- ^ Larvik Museum Society(Frommer's)

- ^ Larvik Museum (visitnorway)

- ^ Larvik Museum (Store norske leksikon)

- ^ "Verkensgården | Larvik, Norway Attractions".

- ^ Treschow-Fritzøe AS (Store norske leksikon)

- ^ Ferguson-Kosinski, Laverne (2015). Europe by Eurail 2016: Touring Europe by Train. Rowman & Littlefield. Page 386. ISBN 9781493012763.

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Page 29).

- ^ "Fritzøehus". 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Fritzøehus - Norges største privatbolig".

- ^ Herregården (Kulturnett.no) Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469.

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Page 23).

- ^ "Herregården in Larvik".

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 22. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Larvik Sjøfartsmuseum (Store norske leksikon)

- ^ Larvik Maritime Museum (Innovation Norway) Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Page 29).

- ^ "Fritzøehus". 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Fritzøehus - Norges største privatbolig".

- ^ Mann i 70-årene omkom

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 68. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ Ebbesen, Jorgen Tandberg (2018). The Sulphureous Bath at Sandefjord in Norway. Sagwan Press. Page 10. ISBN 9781297731068.

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Sandefjord".

- ^ "Goksjø".

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ Børresen, Svein E. (2004). Vestfoldboka: en reise i kultur og natur. Skagerrak forl. Page 96. ISBN 9788292284070.

- ^ Aadnevik, Kjell-Einar (2019). Turguide til Larvik og Omegn. Dreyers forlag. Page 274. ISBN 9788282654418.

- ^ Schandy, Tom and Tom Helgesen (2012). Naturperler i Vestfold. Forlaget Tom & Tom v/Schandy. Page 192. ISBN 9788292916148.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 23. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Krohn-Holm, Jan W. (1971). Larvik: Grevens By. Leif Holktedahls Forlag. Page 58. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999849827902121

- ^ "Bøkeskogen | Larvik, Norway Attractions".

- ^ "Mølen".

- ^ "Mølen".

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Page 16).

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 99. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ "Larvik". 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Vestfold – tidligere fylke". 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Jakt".

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Page 15).

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 6. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ Tollnes, Ivar and Olaf Akselsen (1994). Sandefjord: Den lille storbyen. Sandefjords blad. Page 140. ISBN 9788299070447.

- ^ Doreen, Taylor-Wilkie (2018). Insight Guides Norway. Insight. Page 304. ISBN 978-1780052106.

- ^ Evensberget, Sverre (2016). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465458902.

- ^ "Visit Stavern -Historie".

- ^ "Attractions".

- ^ Ham, Anthony and Stuart Butler (2015). Lonely Planet Norway. Lonely Planet. Page 91. ISBN 978-1742202075.

- ^ Bertelsen, Hans Kristian (1998). Bli kjent med Vestfold / Become acquainted with Vestfold. Stavanger Offset AS. Page 63. ISBN 9788290636017.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469.

- ^ Doreen, Taylor-Wilkie (2018). Insight Guides Norway. Insight. Page 157. ISBN 978-1780052106.

- ^ Aadnevik, Kjell-Einar (2019). Turguide til Larvik og Omegn. Dreyers forlag. Page 54. ISBN 9788282654418.

- ^ Schandy, Tom and Tom Helgesen (2012). Naturperler i Vestfold. Forlaget Tom & Tom v/Schandy. Page 227. ISBN 9788292916148.

- ^ Lund, Arild and Charlotte Jørgensen (2001). Larvik. Capella Media. Page 99. ISBN 978-8299606912.

- ^ "Minnehallen".

- ^ https://issuu.com/visitvestfold/docs/visit_larvik_2018-2019_web (Page 29).

- ^ Ham, Anthony and Stuart Butler (2015). Lonely Planet Norway. Lonely Planet. Page 91. ISBN 978-1742202075.

- ^ Evensberget, Snorre (2014). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Norway. Penguin. Page 129. ISBN 9781465432469.

- ^ "Larvik church".

- ^ Børresen, Svein E. (2004). Vestfoldboka: en reise i kultur og natur. Skagerrak forl. Pages 50-51. ISBN 9788292284070.

- ^ Davidsen, Roger (2008). Et Sted i Sandefjord. Sandar Historielag. Page 144. ISBN 9788299456753.

- ^ Børresen, Svein E. (2004). Vestfoldboka: en reise i kultur og natur. Skagerrak forl. Page 28. ISBN 9788292284070.

- ^ NORDHEIM, LASSE (29 April 2014). "Tar gjerne turen til Larvik oftere". Østlands-Posten. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 30 November 2020

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 30 November 2020

- ^ "Vennskapskommuner". larvik.kommune.no (in Norwegian). Larvik Kommune. Retrieved 2021-01-31.

External links

- opplevlarvik.no Tourist information (in Norwegian)

- ilovelarvik.com (in Norwegian)

Vestfold travel guide from Wikivoyage

Vestfold travel guide from Wikivoyage Larvik travel guide from Wikivoyage

Larvik travel guide from Wikivoyage- iBrunlanes.no (in Norwegian)

- Municipal web site (in Norwegian)

- Live Camera - 10 cameras from Larvik (in Norwegian)

- Larvik Museum official website

- Vestfoldmuseene website

![Kaupang is the oldest town in Norway.[122]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Kaupang%2C_Vestfold_view_22jun2005.jpg/240px-Kaupang%2C_Vestfold_view_22jun2005.jpg)

![Rock settings at Istrehågan resemble a ship.[123][124]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Istre_H%C3%A5gan.jpg/270px-Istre_H%C3%A5gan.jpg)