Kula ring

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Kula, also known as the Kula exchange or Kula ring, is a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring was made famous by Bronisław Malinowski, considered the father of modern anthropology. He used this test case to argue for the universality of rational decision-making and for the cultural nature of the object of their effort. Malinowski's seminal work on the topic, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922),[1] directly confronted the question, "Why would men risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets?" Malinowski carefully traced the network of exchanges of bracelets and necklaces across the Trobriand Islands, and established that they were part of a system of exchange (the Kula ring), and that this exchange system was clearly linked to political authority.

Malinowski's study became the subject of debate with the French anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, author of The Gift ("Essai sur le don", 1925).[2] Since then, the Kula ring has been central to the continuing anthropological debate on the nature of gift-giving, and the existence of gift economies.

Basic description

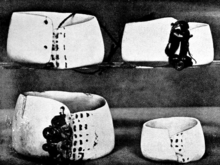

The Kula ring spans 18 island communities of the Massim archipelago, including the Trobriand Islands, and involves thousands of individuals.[3] Participants travel at times hundreds of miles by canoe in order to exchange Kula valuables, which consist of red shell-disc necklaces (veigun or soulava) that are traded to the north (circling the ring in clockwise direction) and white shell armbands (mwali) that are traded in the southern direction (circling counterclockwise). If the opening gift was an armband, then the closing gift must be a necklace and vice versa. The exchange of Kula valuables is also accompanied by the trade in other items known as gimwali (barter). The terms of participation vary from region to region. Whereas on the Trobriand Islands the exchange is monopolised by the chiefs, in Dobu there are between 100 and 150 people involved in Kula trade, between one and two in each matrilineage.[4]

Items for trade

All Kula valuables are non-use items traded purely for purposes of enhancing one's social status and prestige. Carefully prescribed customs and traditions surround the ceremonies that accompany the exchanges which establish strong, ideally lifelong relationships between the exchange parties (karayta'u, "partners"). The act of giving, as Mauss wrote, is a display of the greatness of the giver, accompanied by shows of exaggerated modesty in which the value of what is given is actively played down. (Marcel Mauss (1979), Sociología y Antropología, Ed. Tecnos, Madrid, page. 181) Such a partnership involves strong mutual obligations such as hospitality, protection and assistance. According to the Muyuw, a good Kula relationship should be "like a marriage". Similarly, the saying around Papua is: "once in the Kula, always in the Kula."[5]

Kula valuables never remain for long in the hands of the recipients; rather, they must be passed on to other partners within a certain amount of time, thus constantly circling around the ring. However, even temporary possession brings prestige and status. Important chiefs can have hundreds of partners while less significant participants may only have fewer than a dozen.[6] Even though the vast majority of items that Kula participants have at any given time are not theirs and will be passed on, Damon (1980:281) notes that e.g. amongst the Muyuw all Kula objects are someone's kitoum, meaning they are owned by that person (or by a group). The person owning a valuable as kitoum has full rights of ownership over it: he can keep it, sell it or even destroy it. The Kula valuable or an equivalent item must be returned to the person who owns it as kitoum. For example, the most important Muyuw men own between three and seven Kula valuables as kitoum, while others do not own any. The fact that, at least in theory, all such valuables are someone's kitoum adds a sense of responsibility to the way they are handled, reminding the recipient that he is only a steward of somebody else's possession. (The ownership of a particular valuable is, however, often not known.) Kula valuables can be exchanged as kitoum in a direct exchange between two partners, thus fully transferring the rights of ownership.

Trading and the social hierarchy

The right of participation in Kula exchange is not automatic; one has to "buy" one's way into it through participating in various lower spheres of exchange.[7] The giver-receiver relationship is always asymmetrical: givers are higher in status. Also, Kula valuables are ranked according to value and age, as are the relationships that are created through their exchange. Participants will often strive to obtain particularly valuable and renowned Kula objects whose owner's fame will spread quickly through the archipelago. Such a competition unfolds through different persons offering pokala (offerings) and kaributu (solicitory gifts) to the owner, thus seeking to induce him to engage in a gift exchange relationship involving the desired object. Kula exchange therefore involves a complex system of gifts and countergifts whose rules are laid down by custom. The system is based on trust as obligations are not legally enforceable. However, strong social obligations and the cultural value system, in which liberality is exalted as highest virtue while meanness is condemned as shameful, create powerful pressures to "play by the rules". Those who are perceived as holding on to valuables and as being slow to give them away soon get a bad reputation (cf.[8]).

The Kula trade was organized differently in the more hierarchical parts of the Trobriand islands. There, only chiefs were allowed to engage in Kula exchange. In hierarchical areas, individuals can earn their own kitomu shells, whereas in less hierarchical areas, they are always subject to the claims of matrilineal kin. And lastly, in the hierarchical areas, Kula necklaces and bracelets are saved for external exchange only; stone axe blades are used internally. In less hierarchical areas, exchange partners may lose their valuables to internal claims. As a result, most seek to exchange their Kula valuables with chiefs, who thus become the most successful players. The chiefs have saved their Kula valuables for external trade, and external traders seek to trade with them before they lose their valuables to internal claims.[9]

The Kula exchange system can be viewed as reinforcing status and authority distinctions since the hereditary chiefs own the most important shell valuables and assume the responsibility for organizing and directing the ocean voyages. Damon (1980) notes that large amounts of Kula valuables are handled by a relatively small number of people, e.g. amongst the Muyuw, three men account for over 50 percent of Kula valuables. The ten most influential men control about 90 percent of all and almost 100 percent of the most precious Kula objects. The movement of these valuables and the related relationships determine most of the Muyuw's political alliances. Fortune notes that Kula relationships are fragile, beset with various kinds of manipulation and deceit. But the recent research results of Susanne Kuehling do not support Fortune's emphasis on cheating and even killing in relation to king.[10] The Muyuw for example state that the only way to get ahead in Kula is to lie, commenting that deceit frequently causes Kula relationships to fall apart.[11] Similarly, Malinowski wrote of "many squabbles, deep resentments and even feuds over real or imaginary grievances in the Kula exchange."[12]

Gift versus commodity exchange

The Kula ring is a classic example of Marcel Mauss' distinction between gift and commodity exchange. Melanesians carefully distinguish gift exchange (Kula) and market exchange in the form of barter (gimwali). Both reflect different underlying value systems and cultural customs. The Kula, Mauss wrote, is not supposed to be conducted like gimwali. The former involves a solemn exchange ceremony, a "display of greatness" where the concepts of honour and nobility are central; the latter, in contrast, often done as part of Kula exchange journeys, involves hard bargaining and serves purely economic purposes.[13]

Kula valuables are inalienable in the sense that they (or an equivalent object) have to be returned to the original owner. Those who receive them can pass them on as gifts, but they cannot be sold as commodities (except by the one who owns them as kitoum).

Malinowski, however, highlighted the unusual characteristics of these "gifts". Malinowski placed the emphasis on the exchange of goods between individuals, and their non-altruistic motives for giving the gift: they expected a return of equal or greater value. In other words, reciprocity is an implicit part of gifting; there is no such thing as the "free gift" given without expectation. Mauss, in contrast, emphasized that the gifts were not between individuals, but between representatives of larger collectivities. These gifts were, he argued, a "total prestation" (see Law of obligations) and not a gift in the Western sense of the word. They were not simple, alienable commodities to be bought and sold, but, like the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, embodied the reputation, history, and sense of identity of a "corporate kin group", such as a line of kings. Given the stakes, Mauss asked "why anyone would give them away?" His answer was an enigmatic concept, "the spirit of the gift". A good part of the confusion (and resulting debate) was due to a bad translation of that phrase. Mauss appeared to be arguing that a return gift is given to keep the very relationship between givers alive; a failure to return a gift ends the relationship and the promise of any future gifts. Jonathan Parry has demonstrated that Mauss was arguing instead that the concept of a "pure gift" given altruistically only emerges in societies with a well-developed market ideology, such as the West and India.[14]

Mauss' concept of "total prestations" was further developed by Annette Weiner, who revisited Malinowski's fieldsite in the Trobriand Islands. Her critique was twofold: first, Trobriand Island society is matrilineal, and women hold a great deal of economic and political power. Their exchanges were ignored by Malinowski. Secondly, she developed Mauss's argument about reciprocity and the "spirit of the gift" in terms of "inalienable possessions: the paradox of keeping while giving."[15] Weiner contrasts "moveable goods" which can be exchanged with "immoveable goods" that serve to draw the gifts back (in the Trobriand case, male Kula gifts with women's landed property). She argues that the specific goods given, like Crown Jewels, are so identified with particular groups that, even when given, they are not truly alienated.

Not all societies, however, have these kinds of goods, which depend upon the existence of particular kinds of kinship groups. French anthropologist Maurice Godelier[16] pushed the analysis further in The Enigma of the Gift (1999). Albert Schrauwers has argued that the kinds of societies used as examples by Weiner and Godelier (including the Kula ring in the Trobriands, the potlatch of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, and the Toraja of South Sulawesi, Indonesia) are all characterized by ranked aristocratic kin groups that fit with Claude Lévi-Strauss' model of "House Societies" (where "House" refers to both noble lineage and their landed estate). Total prestations are given, he argues, to preserve landed estates identified with particular kin groups and maintain their place in a ranked society.[17]

See also

- Potlatch, a similar practice among some Native American and First Nations peoples of west coast North America

- Koha, a similar practice among the Māori

- Moka, a similar practice in the Mt. Hagen area of Papua New Guinea

- Sepik Coast exchange, a similar practice in the Sepik Coast of Papua New Guinea

Footnotes

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ^ Mauss, Marcel (1970). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Cohen & West.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ^ The name of the gift : ethics of exchange on Dobu Island, Susanne Kuehling, Australian National University, 1998, p.212

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 82.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 98.

- ^ Damon, F. H. (1980). "The Kula and Generalised Exchange: Considering some Unconsidered Aspects of the Elementary Structures of Kinship". Man (new series) 15: 278.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 100.

- ^ Weiner, Annette (1992). Inalienable Possessions: The paradox of keeping-while-giving. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 137–140.

- ^ The name of the gift : ethics of exchange on Dobu Island, Susanne Kuehling, Australian National University, 1998, p.208

- ^ Damon, F. H. (1980). "The Kula and Generalised Exchange: Considering some Unconsidered Aspects of the Elementary Structures of Kinship". Man (new series) 15: 278.

- ^ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 100.

- ^ Mauss, Marcel (1970). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Cohen & West. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Parry, Jonathan (1986). "The Gift, the Indian Gift and the 'Indian Gift'". Man. 21 (3): 453–73. doi:10.2307/2803096. JSTOR 2803096. S2CID 152071807.

- ^ Weiner, Annette (1992). Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-while-Giving. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Godelier, Maurice (1999). The Enigma of the Gift. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- ^ Schrauwers, Albert (2004). "H(h)ouses, E(e)states and class: On the importance of capitals in central Sulawesi". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 160 (1): 72–94. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003735.

References

- "Kula in Woodlark". Fieldwork report: Logging or conservation on Woodlark (Muyuw) island, by Michael Young, Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2005.

- "Kula: the standard model". Notes for reading Bronislaw Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922). Retrieved March 14, 2005.

- Jerry Leach and Edmund Leach (1983). The Kula: New Perspectives on Massim Exchange. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Damon, F. H. (1980). "The Kula and Generalised Exchange: Considering some Unconsidered Aspects of the Elementary Structures of Kinship". Man. New Series. 15 (2): 267–292. doi:10.2307/2801671. JSTOR 2801671.

- Malinowski, B. (1920). "Kula; the Circulating Exchange of Valuables in the Archipelagoes of Eastern New Guinea". Man. 20. Man, Vol. 20: 97–105. doi:10.2307/2840430. JSTOR 2840430.

- Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. George Routledge & Sons, Ltd.

- Mauss, M. (1990). The Gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. London: Routledge.