Cope rearrangement

| Cope rearrangement | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Arthur C. Cope |

| Reaction type | Rearrangement reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| Organic Chemistry Portal | cope-rearrangement |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000028 |

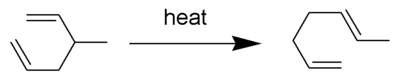

The Cope rearrangement is an extensively studied organic reaction involving the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-dienes.[1][2][3][4] It was developed by Arthur C. Cope and Elizabeth Hardy. For example, 3-methyl-hexa-1,5-diene heated to 300 °C yields hepta-1,5-diene.

The Cope rearrangement causes the fluxional states of the molecules in the bullvalene family.

Mechanism

[edit]The Cope rearrangement is the prototypical example of a concerted sigmatropic rearrangement. It is classified as a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement with the Woodward–Hoffmann symbol [π2s+σ2s+π2s] and is therefore thermally allowed. It is sometimes useful to think of it as going through a transition state energetically and structurally equivalent to a diradical, although the diradical is not usually a true intermediate (potential energy minimum).[5] The chair transition state illustrated here is preferred in open-chain systems (as shown by the Doering-Roth experiments). However, conformationally constrained systems like cis-1,2-divinyl cyclopropanes can undergo the rearrangement in the boat conformation.

It is currently generally accepted that most Cope rearrangements follow an allowed concerted route through a Hückel aromatic transition state and that a diradical intermediate is not formed. However, the concerted reaction can often be asynchronous and electronically perturbed systems may have considerable diradical character at the transition state.[6] A representative illustration of the transition state of the Cope rearrangement of the electronically neutral hexa-1,5-diene is presented below. Here one can see that the two π-bonds are breaking while two new π-bonds are forming, and simultaneously the σ-bond is breaking while a new σ-bond is forming. In contrast to the Claisen rearrangement, Cope rearrangements without strain release or electronic perturbation are often close to thermally neutral, and may therefore reach only partial conversion due to an insufficiently favorable equilibrium constant. In the case of hexa-1,5-diene, the rearrangement is degenerate (the product is identical to the starting material), so K = 1 by necessity.

In asymmetric dienes one often needs to consider the stereochemistry, which in the case of pericyclic reactions, such as the Cope rearrangement, can be predicted with the Woodward–Hoffmann rules and consideration of the preference for the chair transition state geometry.

Examples

[edit]The rearrangement is widely used in organic synthesis. It is symmetry-allowed when it is suprafacial on all components. The transition state of the molecule passes through a boat or chair like transition state. An example of the Cope rearrangement is the expansion of a cyclobutane ring to a cycloocta-1,5-diene ring:

In this case, the reaction must pass through the boat transition state to produce the two cis double bonds. A trans double bond in the ring would be too strained. The reaction occurs under thermal conditions. The driving force of the reaction is the loss of strain from the cyclobutane ring.

An organocatalytic Cope rearrangement was first reported in 2016. In this process, an aldehyde-substituted 1,5-diene is used, allowing "iminium catalysis" to be achieved using a hydrazide catalyst and moderate levels of enantioselectivity (up to 47% ee) to be achieved.[7]

A number of enzymes catalyze the Cope rearrangement, although its occurrence is rare in nature.[8][9]

Oxy-Cope rearrangement and related variants

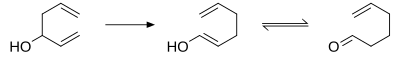

[edit]In the oxy-Cope rearrangement, a hydroxyl group is added at C3 forming an enal or enone after keto-enol tautomerism of the intermediate enol.[10][11][12]

In its original implementation, the oxy-Cope reaction required high temperatures. Subsequent work showed that the corresponding potassium alkoxides rearranged faster by 1010 to 1017.[13] By virtue of this innovation, reaction proceed well at room temperature or even 0 °C. Typically potassium hydride and 18-crown-6 are employed to generate the dissociated potassium alkoxide:[14]

The diastereomer of the starting material shown above with an equatorial vinyl group does not react, providing evidence of the concerted nature of this reaction. Nevertheless, the transition state of the reaction is believed to have a high degree of diradical character. Consequently, the anion-accelerated oxy-Cope reaction can proceed with high efficiency even in systems that do not permit efficient orbital overlap, as illustrated by a key step in the synthesis periplanone B:[15]

![Example from [Stuart Schreiber]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Schreiber.png/600px-Schreiber.png)

The corresponding neutral oxy-Cope and siloxy-Cope rearrangements failed, giving only elimination products at 200 °C.

Another variation of the Cope rearrangement is the aza-Cope rearrangements.

See also

[edit]- Claisen rearrangement, another widely studied [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangement

- divinylcyclopropane-cycloheptadiene rearrangement

References

[edit]- ^ Arthur C. Cope; Elizabeth M. Hardy; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 441.

- ^ Rhoads, S. J.; Raulins, N. R.; Org. React. 1975, 22, 1–252. (Review)

- ^ Hill, R. K.; Compr. Org. Synth. 1991, 5, 785–826.

- ^ Wilson, S. R.; Org. React. 1993, 43, 93–250. (Review)

- ^ Michael B. Smith & Jerry March: March's Advanced Organic Chemistry, pp. 1659-1673. John Wiley & Sons, 2007 ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Williams, R. V., Chem. Rev. 2001, 101 (5), 1185–1204.

- ^ Kaldre, Dainis; Gleason, James L. (2016). "An Organocatalytic Cope Rearrangement". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 55 (38): 11557–11561. doi:10.1002/anie.201606480. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 27529777.

- ^ Tang, Xueke; Xue, Jing; Yang, Yunyun; Ko, Tzu-Ping; Chen, Chin-Yu; Dai, Longhai; Guo, Rey-Ting; Zhang, Yonghui; Chen, Chun-Chi (2019). "Structural insights into the calcium dependence of Stig cyclases". RSC Advances. 9 (23): 13182–13185. doi:10.1039/C9RA00960D. ISSN 2046-2069. PMC 9063808. PMID 35520811.

- ^ Tang, Man-Cheng; Zou, Yi; Watanabe, Kenji; Walsh, Christopher T.; Tang, Yi (2017-04-26). "Oxidative Cyclization in Natural Product Biosynthesis". Chemical Reviews. 117 (8): 5226–5333. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00478. ISSN 0009-2665. PMC 5406274. PMID 27936626.

- ^ A Synthesis of Ketones by the Thermal Isomerization of 3-Hydroxy-1,5-hexadienes. The Oxy-Cope Rearrangement Jerome A. Berson, Maitland Jones, , Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964; 86(22); 5019–5020. doi:10.1021/ja01076a067

- ^ Stepwise Mechanisms in the Oxy-Cope Rearrangement Jerome A. Berson and Maitland Jones pp 5017 – 5018; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964; doi:10.1021/ja01076a066

- ^ Carey, Francis A.; Sundberg, Richard J. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part B: Reactions and Synthesis (5th ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 555–556. ISBN 978-0387683546.

- ^ Carey, Francis A.; Sundberg, Richard J. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part B: Reactions and Synthesis (5th ed.). New York: Springer. p. 556. ISBN 978-0387683546.

- ^ Evans, D. A.; Golob, A. M. (1975). "[3,3]Sigmatropic rearrangements of 1,5-diene alkoxides. Powerful accelerating effects of the alkoxide substituent". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 97 (16): 4765–4766. doi:10.1021/ja00849a054.

- ^ Schreiber, Stuart L.; Santini, Conrad (1984). "Cyclobutene bridgehead olefin route to the American cockroach sex pheromone, periplanone-B". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 106 (14): 4038–4039. doi:10.1021/ja00326a028.