Comb

A comb is a tool consisting of a shaft that holds a row of teeth for pulling through the hair to clean, untangle, or style it. Combs have been used since prehistoric times, having been discovered in very refined forms from settlements dating back to 5,000 years ago in Persia.[1]

Weaving combs made of whalebone dating to the middle and late Iron Age have been found on archaeological digs in Orkney and Somerset.[2]

Description

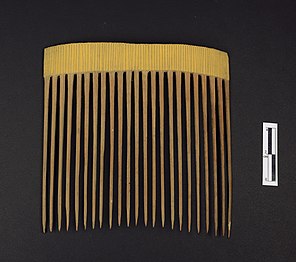

[edit]Combs are made of a shaft and teeth that are placed at a perpendicular angle to the shaft. Combs can be made out of a number of materials, most commonly plastic, metal, or wood. In antiquity, horn and whalebone was sometimes used. Combs made from ivory[3] and tortoiseshell[4] were once common but concerns for the animals that produce them have reduced their usage. Wooden combs are largely made of boxwood, cherry wood, or other fine-grained wood. Good quality wooden combs are usually handmade and polished.[5]

Combs come in various shapes and sizes depending on what they are used for. A hairdressing comb may have a thin, tapered handle for parting hair and close teeth. Common hair combs usually have wider teeth halfway and finer teeth for the rest of the comb.[6] Hot combs were used solely for straightening hair during the colonial era in North America.[7]

A hairbrush comes in both manual and electric models.[8] It is larger than a comb, and is also commonly used for shaping, styling, and cleaning hair.[9] A combination comb and hairbrush was patented in the 19th century.[10]

Uses

[edit]

Combs can be used for many purposes. Historically, their main purpose was securing long hair in place, decorating the hair, matting sections of hair for dreadlocks, or keeping a kippah or skullcap in place. In Spain, a peineta is a large decorative comb used to keep a mantilla in place.[5]

In industry and craft, combs are used in separating cotton fibres from seeds and other debris (the cotton gin, a mechanized version of the comb, is one of the machines that ushered in the Industrial Revolution). A comb is used to distribute colors in paper marbling to make the swirling colour patterns in comb-marbled paper.[11]

Combs are also a tool used by police investigators to collect hair and dandruff samples that can be used in ascertaining dead or living persons' identities, as well as their state of health and toxicological profiles.[12]

Hygiene

[edit]Sharing combs is a common cause of parasitic infections much like sharing a hat, as one user can leave a comb with eggs or live parasites, facilitating the transmission of lice, fleas, mites, fungi, and other undesirables. Siblings are also more likely to pass on nits to each other if they share a comb.[13]

Making music

[edit]Stringing a plant's leaf or a piece of paper over one side of the comb and humming with cropped lips on the opposite side dramatically increases the high-frequency harmonic content of the hum produced by the human voice box, and the resulting spread sound spectrum can be modulated by changing the resonating frequency of the oral cavity.[14] This was the inspiration for the kazoo, a membranophone.

The comb is also a lamellophone. Comb teeth have harmonic qualities of their own, determined by their shape, length, and material. A comb with teeth of unequal length, capable of producing different notes when picked, eventually evolved into the thumb piano[15] and music box.[16]

Types

[edit]Chinese combs

[edit]In China, combs are referred to by the generic term shubi (梳篦) or zhi (栉) and originated about 6000 years ago during the late Neolithic period. Chinese combs are referred as shu (梳) when referring to thick-tooth comb and bi (篦) when referred to thin-tooth comb.[17] A form of shubi produced in Changzhou is the Changzhou comb; the Palace Comb Factory, also called Changzhou combs Factory, found in the city of Changzhou started to operate since the 5th century and continues to produce handmade wooden combs up to this day.[5]: 87 Shubi were also introduced in Japan during the Nara period where they were referred by the generic name kushi.[18]

-

Shu, Shang dynasty comb

-

Qin dynasty comb

-

Western Han jade comb

-

Tang dynasty comb

-

Changzhou comb, double-edged fine-tooth comb

Japanese combs

[edit]In Japan, combs are referred to as kushi. Indigenous Japanese kushi started to be used by Japanese people about 6000 years ago in the Jōmon era. In the Nara period, Chinese combs from the Tang dynasty were introduced in Japan.[18] Another form of comb in Japan is the Satsuma comb, which started to appear around the 17th century and was produced by the samurai warriors of the Satsuma clan as a side job.[19]

-

Kushi made of tortoiseshell with lacquer, Japan, Edo or Taiso period

-

Hana kushi

Liturgical comb

[edit]

A liturgical comb is a decorated comb with used ceremonially in both Catholic and Orthodox Christianity during the Middle Ages, and in Byzantine Rite up to this day.[20]

Nit comb

[edit]

Specialized combs such as "flea combs" or "nit combs" can be used to remove macroscopic parasites and cause them damage by combing.[21] A comb with teeth fine enough to remove nits is sometimes called a "fine-toothed comb", as in the metaphoric usage "go over [something] with a fine-toothed comb", meaning to search closely and in detail. Sometimes in this meaning, "fine-toothed comb" has been reanalysed as "fine toothcomb" and then shortened to "toothcomb", or changed into forms such as "the finest of toothcombs".[22][23]

Afro pick

[edit]An Afro pick is a type of comb having long, thick teeth which is usually used on kinky or Afro-textured hair. It is longer and thinner than the typical comb, and it is sometimes worn in the hair.[24][25]

The history of the Afro pick dates back at least 5,000 years, as a practical tool that may also have cultural and political meaning.[26]

Unbreakable plastic comb

[edit]An unbreakable plastic comb is a comb that, despite being made of plastic rather than (more expensive) metal, does not shatter into multiple pieces if dropped on a hard surface such as bathroom tiles, a hardwood floor, or pavement.[27] Such combs were introduced in the mid-twentieth century.[28] Today most plastic combs are unbreakable as technology has reached a point of understanding the causation of brittleness in these products.[29]

Modern artisan combs

[edit]

Modern artisan combs crafted from a wide variety of new and recycled materials have become popular over recent years. Used skateboard decks, vinyl records,[30] brass, titanium alloy, acrylic, sterling silver, and exotic wood are a few of the materials being used.

Gallery

[edit]-

Ancient Egyptian comb, c. fifteenth century BC

-

Etruscan comb, c. seventh century BC

-

Scythian comb, c. 400 BC

-

Ancient Roman comb, 4th or 5th century AD

-

The world's oldest runic inscription (160 AD) on the Vimose comb, Denmark

-

A set of combs found on the 16th-century ship Mary Rose

-

Ivory sculptured comb, 16th century

-

Indian metal comb for keeping hair in place, adorned with a pair of birds. After removing the central stopper, perfume can be poured into the opening in order to moisten the teeth of the comb and the hair of the wearer.

-

A Punjabi wooden comb

-

Head louse comb

-

Artisan hand-finished metal comb

-

Bamboo comb of the Kanak people

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Vaux, William Sandys Wright (1850). Nineveh and Persepolis: An Historical Sketch of Ancient Assyria and Persia, with an Account of the Recent Researches in Those Countries. A. Hall, Virtue, & Company.

- ^ Helen Chittock, “Arts and crafts in Iron Age Britain: reconsidering the aesthetic effects of weaving combs,” Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 33 (3) August 2014, pp.315-6.

- ^ Sandell, Hanne Tuborg; Sandell, Birger (1991). Archaeology and Environment in the Scoresby Sund Fjord. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788763512084.

- ^ White, Carolyn L. (2005). American Artifacts of Personal Adornment, 1680–1820: A Guide to Identification and Interpretation. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780759105898.

- ^ a b c Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313331459. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ^ Laing, Lloyd Robert (2006). The Archaeology of Celtic Britain and Ireland: C. AD 400–1200. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521838627.

- ^ Hodder, Ian (1997). Interpreting Archaeology: Finding Meaning in the Past. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415157445.

- ^ Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. 1937. p. 39.

- ^ Cooley, Arnold James (1866). The Toilet and Cosmetic Arts in Ancient and Modern Times. R. Hardwicke. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ^ The Canadian Patent Office Record and Register of Copyrights and Trade Marks. Patent Office. 1895. p. 437.

- ^ Wolfe, Richard J. (1990). Marbled Paper: Its History, Techniques, and Patterns: with Special Reference to the Relationship of Marbling to Bookbinding in Europe and the Western World. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812281880.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Frank Dalton; Wright, Walter Edward (1940). Practical Instruction in Police Work and Detective Science: A Course of Instruction ... Containing Lecture-lessons for Law Enforcement Officers and Others. American Police Review Publishing Company.

- ^ Sinha, Meenakshi; Rajgopal, Reena; Banerjee, Suchismita (2012). All You Wanted To Know About Hair Care. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788120791022.

- ^ Green, Douglas (2001). The Everything Lawn Care Book: From Seed to Soil, Mowing to Fertilizing – hundreds of Tips for Growing a Beautiful Lawn. Adams Media. p. 23. ISBN 9781580624879.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nicholls, David (1998). The Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521454292.

- ^ Bulleid, Henry Anthony Vaughan (1994). Cylinder musical box technology: including makers, types, dating, and music. Almar Press. ISBN 9780930256227. Archived from the original on 2016-12-23. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ^ "Chinese Shubi [page 1]". en.chinaculture.org. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ a b Zhang, Linyi (2019). "Comparison of aesthetic styles of decorative combs in Japan and China". วารสารศิลปกรรมบูรพา. 20 (1): 374–384.

- ^ "Satsuma Comb – A Traditional Craft created by Samurai Warriors". Najimu-Japan. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ^ Hourihane, Colum, ed. (2012). The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0195395365.

- ^ Copeland, Lennie (2001). The Lice-Buster Book: What to Do When Your Child Comes Home with Head Lice. Grand Central. ISBN 9780759526297.

- ^ "fine toothcomb/fine-tooth comb". WSU.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ Morewitz, H. (2008). "A Brief History of Lice Combs". Nuvoforheadlice.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Moore, Jennifer Grayer (2015). Fashion Fads Through American History: Fitting Clothes into Context. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610699020.

- ^ Jet. Johnson. 1972.

- ^ "Origins of the Afro Comb". cam.ac.uk.

- ^ Adams, Glenn Arthur (2000). A Likely Story. iUniverse. ISBN 9780595004294. Archived from the original on 2016-12-23. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ^ Division, Great Britain Central Office of Information Reference (1951). Home Affairs Survey.

- ^ International, A. S. M.; Lampman, Steve (2003). Characterization and Failure Analysis of Plastics. ASM International. ISBN 9781615030736.

- ^ "Tame your hipster beard with a comb made from what?". Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

External links

[edit]- Ashby, S. (2011). "An Atlas of Medieval Combs from Northern Europe". Internet Archaeology (30). doi:10.11141/ia.30.3.

- Ireland, Kay. "Cómo usar un peine navaje (How to Use Razor Combs)". eHow en Espanol (in Spanish).

- "The Origin of Combs". TheOriginOf.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2008-09-11.