Operation Chastise

| Operation Chastise | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second World War | |||||||

The Möhne dam the day following the attacks | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 19 Lancaster bombers |

XII. Fliegerkorps (Defending three dams) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

8 aircraft lost 53 aircrew killed 3 aircrew taken prisoner. |

2 dams breached 1 dam lightly damaged c. 1,600 civilians killed (including c. 1,000 prisoners and slave labourers, mainly Soviet) | ||||||

Operation Chastise, commonly known as the Dambusters Raid,[1][2] was an attack on German dams carried out on the night of 16/17 May 1943 by 617 Squadron RAF Bomber Command, later called the Dam Busters, using special "bouncing bombs" developed by Barnes Wallis. The Möhne and Edersee dams were breached, causing catastrophic flooding of the Ruhr valley and of villages in the Eder valley; the Sorpe Dam sustained only minor damage. Two hydroelectric power stations were destroyed and several more damaged. Factories and mines were also damaged and destroyed. An estimated 1,600 civilians – about 600 Germans and 1,000 enslaved labourers, mainly Soviet – were killed by the flooding. Despite rapid repairs by the Germans, production did not return to normal until September. The RAF lost 56 aircrew, with 53 dead and 3 captured, amid losses of 8 aircraft.

Background

Before the Second World War, the British Air Ministry had identified the industrialised Ruhr Valley, especially its dams, as important strategic targets.[3] The dams provided hydroelectric power and pure water for steel-making, drinking water and water for the canal transport system. Calculations indicated that attacks with large bombs could be effective but required a degree of accuracy which RAF Bomber Command had been unable to attain when attacking a well-defended target. A one-off surprise attack might succeed but the RAF lacked a weapon suitable for the task.[4]

Concept

The mission grew out of a concept for a bomb designed by Barnes Wallis, assistant chief designer at Vickers.[4] Wallis had worked on the Vickers Wellesley and Vickers Wellington bombers and while working on the Vickers Windsor, he had also begun work, with Admiralty support, on an anti-shipping bomb, although dam destruction was soon considered. At first, Wallis wanted to drop a 10-long-ton (22,000 lb; 10,000 kg) bomb from an altitude of about 40,000 ft (12,000 m), part of the earthquake bomb concept. No bomber aircraft was capable of flying at such an altitude or of carrying such a heavy bomb and although Wallis proposed the six-engined Victory Bomber for this purpose this was rejected.[5] Wallis realized that a much smaller explosive charge would suffice if it exploded against the dam wall under the water but German reservoir dams were protected by heavy torpedo nets to prevent an explosive device from travelling through the water.[6]

Wallis devised a 9,000 lb (4,100 kg) bomb (more accurately, a mine) in the shape of a cylinder, equivalent to a very large depth charge armed with a hydrostatic fuse, designed to be given a backspin of 500 rpm. Dropped at 60 ft (18 m) and 240 mph (390 km/h) from the release point, the mine would skip across the surface of the water before hitting the dam wall as its forward speed ceased. Initially the backspin was intended to increase the range of the mine but it was later realized that it would cause the mine, after submerging, to run down the side of the dam towards its base, thus maximising the explosive effect against the dam.[7] This weapon was code-named Upkeep.[8]

Testing of the concept included blowing up a scale model dam at the Building Research Establishment, Watford, in May 1942 and then the breaching of the disused Nant-y-Gro dam in Wales in July. A subsequent test suggested that a charge of 7,500 lb (3,400 kg) exploded 30 ft (9.1 m) under water would breach a full-size dam; crucially this weight would be within the carrying capacity of an Avro Lancaster.[9] The first air drop trials were at Chesil Beach in December 1942; these used a spinning 4 ft 6 in sphere dropped from a modified Vickers Wellington, serial BJ895/G; the same aircraft was used until April 1943 when the first modified Lancasters became available. The tests continued at Chesil Beach and Reculver, often unsuccessfully, using revised designs of the mine and variations of speed and height.

Avro Chief Designer Roy Chadwick adapted the Lancaster to carry the mine. To reduce weight, much of the internal armour was removed, as was the mid-upper (dorsal) gun turret. The dimensions of the mine and its unusual shape meant that the bomb-bay doors had to be removed and the mine hung partly below the fuselage. It was mounted on two crutches and before dropping it was spun by an auxiliary motor. Chadwick also worked out the design and installation of controls and gear for the carriage and release of the mine in conjunction with Barnes Wallis. The Avro Lancaster B Mk IIIs so modified were known as Lancaster B Mark III Special (Type 464 Provisioning).[10][11]

In February 1943, Air Vice-Marshal Francis Linnell at the Ministry of Aircraft Production thought the work was diverting Wallis from the development of the Vickers Windsor bomber (which did not become operational). Pressure from Linnell via the chairman of Vickers, Sir Charles Worthington Craven, caused Wallis to offer to resign.[12] Sir Arthur Harris, head of Bomber Command, after a briefing by Linnell also opposed the allocation of his bombers; Harris was about to start the strategic bombing campaign against Germany and Lancasters were just entering service. Wallis had written to an influential intelligence officer, Group Captain Frederick Winterbotham, who ensured that the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal, heard of the project. Portal saw the film of the Chesil Beach trials and was convinced.[13] On 26 February 1943, Portal over-ruled Harris and ordered that thirty Lancasters were to be allocated to the mission and the target date was set for May, when water levels would be at their highest and breaches in the dams would cause the most damage.[14] With eight weeks to go, the larger Upkeep mine that was needed for the mission and the modifications to the Lancasters had yet to be designed.

Assignment

The operation was given to No. 5 Group RAF, which formed a new squadron to undertake the dams mission. It was initially called Squadron X, as the speed of its formation outstripped the RAF process for naming squadrons. Led by 24-year-old Wing Commander Guy Gibson, a veteran of more than 170 bombing and night-fighter missions, twenty-one bomber crews were selected from 5 Group squadrons. The crews included RAF personnel of several nationalities, members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). The squadron was based at RAF Scampton, about 5 mi (8 km) north of Lincoln.

The targets selected were the Möhne Dam and the Sorpe Dam, upstream from the Ruhr industrial area, with the Eder Dam on the Eder River, which feeds into the Weser, as a secondary target. The loss of hydroelectric power was important but the loss of water to industry, cities and canals would have greater effect and there was potential for devastating flooding if the dams broke.

Preparations

Bombing from an altitude of 60 ft (18 m), at an air speed of 240 mph (390 km/h) and at set distance from the target called for expert crews. Intensive night-time and low-altitude training began. There were also technical problems to solve, the first one being to determine when the aircraft was at optimum distance from its target. The Möhne and Eder Dams had towers at each end. A special targeting device with two prongs, making the same angle as the two towers at the correct distance from the dam, showed when to release the bomb. (The BBC documentary Dambusters Declassified (2010) stated that the pronged device was not used, owing to problems related to vibration and that other methods were employed, including a length of string tied in a loop and pulled back centrally to a fixed point in the manner of a catapult.)

The second problem was determining the aircraft's altitude, as barometric altimeters lacked accuracy. Two spotlights were mounted, one under the aircraft's nose and the other under the fuselage, so that at the correct height their light beams would converge on the surface of the water. The crews practised at the Eyebrook Reservoir, near Uppingham, Rutland; Abberton Reservoir near Colchester; Derwent Reservoir in the Derbyshire Peak District; and Fleet Lagoon on Chesil Beach. Wallis's bomb was first tested at the Elan Valley Reservoirs.

Gibson also had VHF radios (normally reserved for fighters) fitted to the Lancasters so that he could control the operation while over the target,[15] an early example of what became the master bomber role.

The squadron took delivery of the bombs on 13 May, after the final tests on 29 April. At 18:00 on 15 May, at a meeting in Whitworth's house, Gibson and Wallis briefed the squadron's two flight commanders, Squadron Leader Henry Eric Maudslay and Sqn Ldr H. M. "Dinghy" Young, Gibson's deputy for the Möhne attack, Flt Lt John V. Hopgood and the squadron bombing leader, Flight Lieutenant Bob Hay. The rest of the crews were told at a series of briefings the following day, which began with a briefing of pilots, navigators and bomb-aimers at about midday.

Organisation

Formation No. 1 was composed of nine aircraft in three groups (listed by pilot): Gibson, Hopgood and Flt Lt H. B. "Micky" Martin (an Australian serving in the RAF); Young, Flt Lt David Maltby and Flt Lt Dave Shannon (RAAF); and Maudslay, Flt Lt Bill Astell and Pilot Officer Les Knight (RAAF). Its mission was to attack the Möhne; any aircraft with bombs remaining would then attack the Eder.

Formation No. 2, numbering five aircraft, piloted by Flt Lt Joe McCarthy (an American serving in the RCAF), P/O Vernon Byers (RCAF),[16] Flt Lt Norman Barlow (RAAF), P/O Geoff Rice[17] and Flt Lt Les Munro (RNZAF), was to attack the Sorpe.

Formation No. 3 was a mobile reserve consisting of aircraft piloted by Flight Sergeant Cyril Anderson, Flt Sgt Bill Townsend, Flt Sgt Ken Brown (RCAF), P/O Warner Ottley and P/O Lewis Burpee (RCAF), taking off two hours later on 17 May, either to bomb the main dams or to attack three smaller secondary target dams: the Lister, the Ennepe and the Diemel.

Two crews were unable to make the mission owing to illness.

The Operations Room for the mission was at 5 Group Headquarters in St Vincents Hall, Grantham, Lincolnshire. The mission codes (transmitted in morse) were: Goner, meaning "bomb dropped"; Nigger, meaning that the Möhne was breached; and Dinghy, meaning that the Eder was breached. Nigger was the name of Gibson's dog, a black labrador retriever that had been run over and killed on the morning of the attack.[18] Dinghy was Young's nickname, a reference to the fact that he had twice survived crash landings at sea where he and his crew were rescued from the aircraft's inflatable rubber dinghy.

The attacks

Outbound

The aircraft used two routes, carefully avoiding known concentrations of flak, and were timed to cross the enemy coast simultaneously. The first aircraft, those of Formation No. 2 and heading for the longer, northern route, took off at 21:28 on 16 May.[19] McCarthy's bomber developed a coolant leak and he took off in the reserve aircraft 34 minutes late.[20]

Formation No. 1 took off in groups of three at 10-minute intervals beginning at 21:39.[19] The reserve formation did not begin taking off until 00:09 on 17 May.[19]

Formation No. 1 entered continental Europe between Walcheren and Schouwen, flew over the Netherlands, skirted the airbases at Gilze-Rijen and Eindhoven, curved around the Ruhr defences, and turned north to avoid Hamm before turning south to head for the Möhne River. Formation No. 2 flew further north, cutting over Vlieland and crossing the IJsselmeer before joining the first route near Wesel and then flying south beyond the Möhne to the Sorpe River.[21]

The bombers flew low, at about 100 ft (30 m) altitude, to avoid radar detection. Flight Sergeant George Chalmers, radio operator on "O for Orange", looked out through the astrodome and was astonished to see that his pilot was flying towards the target along a forest's firebreak, below treetop level.[22]

First casualties

The first casualties were suffered soon after reaching the Dutch coast. Formation No. 2 did not fare well: Munro's aircraft lost its radio to flak and turned back over the IJsselmeer, while Rice[17] flew too low and struck the sea, losing his bomb in the water; he recovered and returned to base. After the completion of the raid Gibson sympathised with Rice, telling him how he had also nearly lost his bomb to the sea. Barlow and Byers crossed the coast around the island of Texel. Byers was shot down by flak shortly afterwards, crashing into the Waddenzee. Barlow's aircraft hit electricity pylons and crashed 5 km east of Rees, near Haldern. The bomb was thrown clear of the crash and was examined intact by Heinz Schweizer.[23] Only the delayed bomber piloted by McCarthy survived to cross the Netherlands. Formation No. 1 lost Astell's bomber near the German hamlet of Marbeck when his Lancaster hit high voltage electrical cables and crashed into a field.[19]

Attack on the Möhne Dam

Formation No. 1 arrived over the Möhne lake and Gibson's aircraft (G for George) made the first run, followed by Hopgood (M for Mother). Hopgood's aircraft was hit by flak as it made its low-level run and was caught in the blast of its own bomb, crashing shortly afterwards when a wing disintegrated. Three crew members successfully abandoned the aircraft, but only two survived. Subsequently, Gibson flew his aircraft across the dam to draw the flak away from Martin's run. Martin (P for Popsie) bombed third; his aircraft was damaged, but made a successful attack. Next, Young (A for Apple) made a successful run, and after him Maltby (J for Johnny), when finally the dam was breached. Gibson, with Young accompanying, led Shannon, Maudslay and Knight to the Eder.[19]

Attack on the Eder Dam

The Eder Valley was covered by heavy fog, but the dam was not defended with anti-aircraft positions as the difficult topography of the surrounding hills was thought to make an attack virtually impossible. With approach so difficult the first aircraft, Shannon's, made six runs before taking a break. Maudslay (Z for Zebra) then attempted a run but the bomb struck the top of the dam and the aircraft was severely damaged in the blast. Shannon made another run and successfully dropped his bomb. The final bomb of the formation, from Knight's aircraft (N for Nut), breached the dam.[24]

Attacks on the Sorpe and Ennepe Dams

The Sorpe dam was the one least likely to be breached. It was a huge earthen dam, unlike the two concrete-and-steel gravity dams that were attacked successfully. Due to various problems, only two Lancasters reached the Sorpe Dam: Joe McCarthy (in T for Tommy, a delayed aircraft from the second wave) and later Brown (F for Freddie) from the third formation. This attack differed from the previous ones in two ways: the 'Upkeep' bomb was not spun, and due to the topography of the valley the approach was made along the length of the dam, not at right angles over the reservoir.

McCarthy's plane was on its own when it arrived over the Sorpe Dam at 00:15 hours, and realised the approach was even more difficult than expected: the flight path led over a church steeple in the village of Langscheid, located on the hillcrest overlooking the dam. With only seconds to go before the bomber had to pull up, to avoid hitting the hillside at the other end of the dam, the bomb aimer George Johnson had no time to correct the bomber's height and heading.

McCarthy made nine attempted bombing runs before Johnson was satisfied. The 'Upkeep' bomb was dropped on the tenth run. The bomb exploded but when he turned his Lancaster to assess the damage, it turned out that only a section of the crest of the dam had been blown off; the main body of the dam remained.

Three of the reserve aircraft had been directed to the Sorpe Dam. Burpee (S for Sugar) never arrived, and it was later determined that the plane had been shot down while skirting the Gilze-Rijen airfield. Brown (F for Freddie) reached the Sorpe Dam: in the increasingly dense fog, after 7 runs, Brown conferred with his bomb aimer and dropped incendiary devices on either side of the valley, which ignited a fire which subsequently lifted the fog enough to drop a direct hit on the eighth run. The bomb cracked but failed to breach the dam. Anderson (Y for York) never arrived having been delayed by damage to his rear turret and dense fog which made his attempts to find the target impossible. The remaining two bombers were then sent to secondary targets, with Ottley (C for Charlie) being shot down en route to the Lister Dam. Townsend (O for Orange) eventually dropped his bomb at the Ennepe Dam without harming it.[19]

Possible attack on Bever Dam

There is some evidence that Townsend might have attacked the Bever Dam by mistake rather than the Ennepe Dam.[25] The War Diary of the German Naval Staff reported that the Bever Dam was attacked at nearly the same time that the Sorpe Dam was. In addition, the Wupperverband authority responsible for the Bever Dam is said to have recovered the remains of a "mine"; and Paul Keiser, a 19-year-old soldier on leave at his home close to the Bever Dam, reported a bomber making several approaches to the dam and then dropping a bomb that caused a large explosion and a great pillar of flame.

In the book The Dambusters' Raid, author John Sweetman suggests Townsend's report of the moon's reflecting on the mist and water is consistent with an attack that was heading to the Bever Dam rather than to the Ennepe Dam, given the moon's azimuth and altitude during the bombing attacks. Sweetman also points out that the Ennepe-Wasserverband authority was adamant that only a single bomb was dropped near the Ennepe Dam during the entire war, and that this bomb fell into the woods by the side of the dam, not in the water, as in Townsend's report. Finally, members of Townsend's crew independently reported seeing a manor house and attacking an earthen dam, which is consistent with the Bever Dam rather than the Ennepe Dam. The main evidence supporting the hypothesis of an attack of the Ennepe Dam is Townsend's post-flight report that he attacked the Ennepe Dam on a heading of 355 degrees magnetic. Assuming that the heading was incorrect, all other evidence points toward an attack on the Bever Dam.[25]

Townsend reported difficulty in finding his dam, and in his post-raid report he complained that the map of the Ennepe Dam was incorrect. The Bever Dam is only about 5 mi (8 km) southwest of the Ennepe Dam. With the early-morning fog that filled the valleys, it would be understandable for him to have mistaken the two reservoirs.

Return flight

On the way back, flying again at treetop level, two more Lancasters were lost. The damaged aircraft of Maudslay was struck by flak near Netterden, and Young's (A for Apple) was hit by flak north of IJmuiden and crashed into the North Sea just off the coast of the Netherlands.[19] On the return flight over the Dutch coast, some German flak aimed at the aircraft was aimed so low that shells were seen to bounce off the sea.[26]

Eleven bombers began landing at Scampton at 03:11 hours, with Gibson returning at 04:15. The last of the survivors, Townsend's bomber, landed at 06:15.[19] It was the last to land because one of its engines had been shut down after passing the Dutch coast. Air Chief Marshal Harris was among those who came out to greet the last crew to land.[27]

List of aircraft involved

| Aircraft call sign | Commander | Target | Attacked target? | Hit target? | Breached target? | Returned? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Wave | |||||||

| G George | Gibson | Möhne Dam | Yes | No | — | Yes | Raid leader. Mine exploded short of dam. Used aircraft to draw anti-aircraft fire away from other crews. |

| M Mother | Hopgood | Yes | No | — | No | Hit by anti-aircraft fire outbound. Mine bounced over dam. Shot down over the target while attacking. (P/O Fraser and P/O Burcher survived) | |

| P Peter (Popsie) | Martin | Yes | No | — | Yes | Mine missed the target. | |

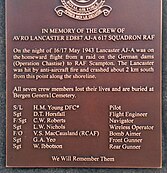

| A Apple | Young | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Mine hit dam and caused small breach. On the homeward flight Lancaster AJ-A was hit by anti-aircraft fire and crashed along the shoreline 2 km south of the Dutch coastal resort of Castricum aan Zee. All seven crew members lost their lives and are buried at the Bergen General Cemetery. | |

| J Johnny | Maltby | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mine hit dam and caused a large breach. | |

| L Leather | Shannon | Eder Dam | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Mine hit target—no effect. |

| Z Zebra | Maudslay | Yes | No | — | No | Mine overshot target and damaged the bomber, which was shot down over Germany while trying to return. | |

| N Nancy (Nan) | Knight | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mine hit the dam and caused a large breach. | |

| B Baker | Astell | N/A | No | — | — | No | Crashed after hitting large-scale power lines outbound. |

| Second Wave | |||||||

| T Tommy | McCarthy | Sorpe Dam | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Mine hit the target – no apparent effect. |

| E Easy | Barlow | N/A | No | — | — | No | Crashed after hitting power lines outbound. |

| K King | Byers | No | — | — | No | Shot down over the Dutch coast outbound. | |

| H Harry | Rice | No | — | — | Yes | Lost the mine after clipping the sea outbound. Returned without attacking a target. | |

| W Willie | Munro | No | — | — | Yes | Damaged by anti-aircraft fire over the Dutch coast. Returned without attacking a target. | |

| Third Wave | |||||||

| Y York | Anderson | Sorpe Dam | No | — | — | Yes | Could not find the target due to mist. Landed at Scampton with an armed mine. |

| F Freddy | Brown | Sorpe Dam | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Mine hit the target – no apparent effect. |

| O Orange | Townsend | Ennepe or Bever Dam | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Mine hit the target – no apparent effect. |

| S Sugar | Burpee | N/A | No | — | — | No | Shot down over the Netherlands outbound. |

| C Charlie | Ottley | No | — | — | No | Shot down over Germany outbound. Frederick Tees was the sole survivor | |

| Totals | 19 aircraft | 4 dams | 11 of 19 | 7 of 11 | 3 of 7 | 11 of 19 | 2 hit power lines outbound; 3 shot down outbound; 3 returned without attacking;

11 attacked; 1 shot down over target; 2 shot down homebound; 8 attacked target and returned. |

Bomb damage assessment

Bomber Command wanted a bomb damage assessment as soon as possible and the CO of 542 Squadron was informed of the estimated time of the attacks. A photo-reconnaissance Spitfire, piloted by Flying Officer Frank 'Jerry' Fray, took off from RAF Benson at 07:30 hours and arrived over the Ruhr River some hours after first light.[28] Photos were taken of the breached dams and the huge floods.[29] The pilot later described the experience:

When I was about 150 miles [240 km] from the Möhne Dam, I could see the industrial haze over the Ruhr area and what appeared to be a cloud to the east. On flying closer, I saw that what had seemed to be cloud was the sun shining on the floodwaters. I looked down into the deep valley which had seemed so peaceful three days before but now it was a wide torrent. The whole valley of the river was inundated with only patches of high ground and the tops of trees and church steeples showing above the flood. I was overcome by the immensity of it.

— Jerry Fray[28]

After the raid

Three aircrew from Hopgood's aircraft parachuted but one later died from wounds and the others were captured. A crewman in Ottley's aircraft survived its crash. In total, therefore, 53 of the 133 aircrew who participated in the attack were killed, a casualty rate of almost 40 percent. Thirteen of those killed were members of the RCAF and two belonged to the RAAF.[30]

Of the survivors, 34 were decorated at Buckingham Palace on 22 June, with Gibson awarded the Victoria Cross. There were five Distinguished Service Orders, 10 Distinguished Flying Crosses and four bars, two Conspicuous Gallantry Medals, eleven Distinguished Flying Medals and one bar.[31]

Initial German casualty estimates from the floods were 1,294 killed, including 749 French, Belgian, Dutch and Ukrainian prisoners of war and labourers.[32][33] Later estimates put the death toll in the Möhne Valley at about 1,600, including people who drowned in the flood wave downstream from the dam.[citation needed]

After a public relations tour of North America, and time spent working in the Air Ministry in London writing the book published as Enemy Coast Ahead, Gibson returned to operations and was killed on a Mosquito operation in 1944.

Following the Dams Raid, 617 Squadron was kept together as a specialist unit. A motto, Après moi le déluge ("After me the flood"), and a squadron badge were chosen. According to Paul Brickhill there was some controversy over the motto, with the original version Après nous le déluge ("After us the flood") being rejected by the Heralds as having inappropriate provenance (having been coined, reportedly, by Madame de Pompadour) and après moi le déluge having been said by Louis XV in an "irresponsible" context. The motto having been chosen by King George VI, the latter was finally deemed acceptable.[34] The squadron went on to drop the Tallboy and Grand Slam bombs and attacked the German battleship Tirpitz, using an advanced bomb sight, which enabled the bombing of small targets with far greater accuracy than conventional bomb aiming techniques.

In 1977, Article 56 of the Protocol I amendment to the Geneva Conventions outlawed attacks on dams "if such attack may cause the release of dangerous forces from the works or installations and consequent severe losses among the civilian population". There is however an exception if "it is used for other than its normal function and in regular, significant and direct support of military operations and if such attack is the only feasible way to terminate such support".[35]

The last surviving member of the 617 Squadron (aka Dambusters) responsible for the Operation, Johnny Johnson, died in 2022.[36][37]

Effect on the war

Tactical view

The two direct mine hits on the Möhnesee dam resulted in a breach around 250 feet (76 m) wide and 292 feet (89 m) deep. The destroyed dam poured around 330 million tons of water into the western Ruhr region. A torrent of water around 33 feet (10 m) high and travelling at around 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) swept through the valleys of the Möhne and Ruhr rivers. A few mines were flooded; 11 small factories and 92 houses were destroyed and 114 factories and 971 houses were damaged. The floods washed away about 25 roads, railways and bridges as the flood waters spread for around 50 miles (80 km) from the source. Estimates show that before 15 May 1943 steel production on the Ruhr was 1 million tonnes;[citation needed][clarification needed] this dropped to a quarter of that level after the raid.

The Eder drains towards the east into the Fulda which runs into the Weser to the North Sea. The main purpose of the Edersee was then, as it is now, to act as a reservoir to keep the Weser and the Mittellandkanal navigable during the summer months. The wave from the breach was not strong enough to result in significant damage by the time it hit Kassel, approximately 22 miles (35 km) downstream.

The greatest impact on the Ruhr armaments production was the loss of hydroelectric power. Two power stations (producing 5,100 kilowatts) associated with the dam were destroyed and seven others were damaged. This resulted in a loss of electrical power in the factories and many households in the region for two weeks. In May 1943 coal production dropped by 400,000 tons which German sources attribute to the effects of the raid.[38]

According to an article by German historian Ralf Blank,[39] at least 1,650 people were killed: around 70 of these were in the Eder Valley, and at least 1,579 bodies were found along the Möhne and Ruhr rivers, with hundreds missing. Of the bodies found downriver of the Möhne Dam, 1,026 were foreign prisoners of war and forced labourers in different camps, mainly from the Soviet Union. Worst hit was the city of Neheim (now part of Neheim-Hüsten) at the confluence of the Möhne and Ruhr rivers, where over 800 people perished, among them at least 493 female forced labourers from the Soviet Union. Some non-German sources cite an earlier total of 749 for all foreigners in all camps in the Möhne and Ruhr valleys as the casualty count at a camp just below the Eder Dam.[33]) One source states that the raid was no more than a minor inconvenience to the Ruhr's industrial output, although that is contradicted by others.[40] The bombing boosted British morale.[41]

In his book Inside the Third Reich, Albert Speer acknowledged the attempt: "That night, employing just a few bombers, the British came close to a success which would have been greater than anything they had achieved hitherto with a commitment of thousands of bombers."[42] He also expressed puzzlement at the raids: the disruption of temporarily having to shift 7,000 construction workers to the Möhne and Eder repairs was offset by the failure of the Allies to follow up with additional (conventional) raids during the dams' reconstruction, and that represented a major lost opportunity.[43] Barnes Wallis was also of this view; he revealed his deep frustration that Bomber Command never sent a high-level bombing force to hit the Möhne dam while repairs were being carried out. He argued that extreme precision would have been unnecessary and that even a few hits by conventional HE bombs would have prevented the rapid repair of the dam which was undertaken by the Germans.[44]

Strategic view

The Dams Raid was, like many British air raids, undertaken with a view to the need to keep drawing German defensive effort back into Germany and away from actual and potential theatres of ground war, a policy which culminated in the Berlin raids of the winter of 1943–1944. In May 1943 this meant keeping the Luftwaffe aircraft and anti-aircraft defences away from the Soviet Union; in early 1944, it meant clearing the way for the aerial side of the forthcoming Operation Overlord. The considerable amount of labour and strategic resources committed to repairing the dams, factories, mines and railways could not be used in other ways, on the construction of the Atlantic Wall, for example. The pictures of the broken dams proved to be a propaganda and morale boost to the Allies, especially to the British, still suffering from the German bombing of the Baedeker Blitz that had peaked roughly a year earlier.[28]

Even within Germany, as evidenced by Gauleiters' reports to Berlin at the time, the German population regarded the raids as a legitimate attack on military targets and thought they were "an extraordinary success on the part of the English" [sic]. They were not regarded as a pure terror attack by the Germans, even in the Ruhr region, and in response the German authorities released relatively accurate (not exaggerated) estimates of the dead.[45]

An effect of the dam raids was that Barnes Wallis's ideas on earthquake bombing, which had previously been rejected, came to be accepted by 'Bomber' Harris. Prior to this raid, bombing had used the tactic of area bombardment with many light bombs, in the hope that one would hit the target. Work on the earthquake bombs resulted in the Tallboy and Grand Slam weapons, which caused damage to German infrastructure in the later stages of the war. They rendered the V-2 rocket launch complex at Calais unusable, buried the V-3 guns, and destroyed bridges and other fortified installations, such as the Grand Slam attack on the railway viaduct at Bielefeld. The most notable successes were the partial collapse of 20-foot-thick (6 m) reinforced concrete roofs of U-boat pens at Brest, and the sinking of the battleship Tirpitz.

Harris regarded the raid as a failure and a waste of resources.[46]

Books and film

The raid was the subject of two books, Enemy Coast Ahead (1946) by Guy Gibson and The Dam Busters (1951) by Paul Brickhill, and a film, The Dam Busters (1955).

Memorials

-

Plaque on the monument to the German victims of the bombing of the Möhne dam, called there the "Möhne catastrophe"

-

Details in Germany of Operation Chastise at the Möhne dam memorial entrance

-

Memorial to Operation Chastise members at Woodhall Spa, Lincolnshire

-

Memorial at Castricum aan Zee

-

Memorial at Castricum aan Zee

See also

- Attack on the Sui-ho Dam during the Korean War

- Dam failure

- Hydroelectric power station failures

- Operation Eisenhammer, a German plan to wreck critical Soviet hydroelectric turbines in World War II

- Operation Garlic, an attack by 617 Squadron on the Dortmund-Ems Canal

- Proposed bombing of Vietnam's dikes

- Noah Wolff – German Jewish industrialist and philanthropist (1809–1907)

- Destruction of the Kakhovka Dam

References

Notes

- ^ "Just how much of a strategic success was the Dambuster raid?". Sky HISTORY TV channel. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "The story of the Dambusters". RAF Benevolent Fund. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Ashworth 1995, p. 76.

- ^ a b Ashworth 1995, p. 77.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, pp. 60–62.

- ^ "Lancaster Bomber Specification." The Dambusters (617 Squadron) via web.archive.org, 2008. Retrieved: 10 October 2010.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Sweetman 1999, p. 78.

- ^ BBC Timewatch programme "Dam Busters: The Race to Smash the German Dams", 8 November 2011

- ^ Sweetman 1999, p. 79.

- ^ Leo McKinstry (2010) Lancaster John Murray Publishers ISBN 978-0-7195-2363-2. p. 277

- ^ Holland 2012, p. 210.

- ^ a b "Geoffrey Rice DFC of RAF 617 Squadron Dambusters". www.hinckleypastpresent.org. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "Avro Lancaster Mk I." Warbird Photo Album. Retrieved: 16 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "617 Squadron, The Operational Record Book 1943–1945, pp. 22–30." Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Dambusters.org.uk, 15 February 2009. Retrieved: 15 May 2009.

- ^ Sweetman 1982, p. 128.

- ^ Sweetman 1982, p. 124.

- ^ Sweetman 1982, p. 135.

- ^ Jasper Copping (5 May 2013). "New German plaque for downed Dambuster bomber". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Obituary: Flying Officer Ray Grayston." telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved: 16 July 2010.

- ^ a b Sweetman 1999, pp. 222–224.

- ^ "Obituary: George Chalmers." The Daily Telegraph, 11 August 2002. Retrieved: 4 February 2008.

- ^ Holland 2012, p. 345.

- ^ a b c Foggo, Daniel and Michael Burke. "I captured proof of Dambusters' raid". The Sunday Telegraph 15 January 2001. Retrieved: 1 February 2008.

- ^ Falconer, Jonathan and Chris Staerck. Allied Photo Reconnaissance of World War II. London: PRC Publishing Ltd., 1998. ISBN 1-57145-161-7.

- ^ Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 2005, Operation Chastise: The Dams Raid, 16/17 May 1943, pp. 4–5. Access date: 16 January 2011.

- ^ "No. 36030". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 May 1943. pp. 2361–2362.

- ^ "Casualties of the Dams Raid." Archived 25 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine RAF Museum. Retrieved: 11 October 2009.

- ^ a b "On This Day: 17 May 1943 – RAF raid smashes German dams". BBC.

- ^ Brickhill 1951, pp. 84, 102.

- ^ "Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977." [ICRC Treaties and Documents]. Retrieved: 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Johnny Johnson: Goodbye to the last Dambuster". UK Aviation News. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Tributes paid as last surviving Dambuster Johnny Johnson dies". BBC News. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "The Dambusters raid: How effective was it?". BBC News. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Blank, Ralf (May 2006). "Die Nacht vom 16. auf den 17. Mai 1943 – 'Operation Züchtigung': Die Zerstörung der Möhne-Talsperre". Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe (in German). Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- ^ Falconer 2007, pp. 89–90.

- ^ "How effective was the Dambusters raid?". BBC News. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Speer 1999, p. 384.

- ^ Speer 1999, p. 385.

- ^ Max Hastings, Bomber Command, p. 262

- ^ The German War – N Stargardt – 2015 – p. 361.

- ^ McKinstry, Leo (15 August 2009). "Bomber Harris thought the Dambusters' attacks on Germany 'achieved nothing'". Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

Bibliography

- Arthur, Max. Dambusters: A Landmark Oral History. London: Virgin Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1-905264-33-9.

- Ashworth, Chris (1995). RAF Bomber Command 1936–1968. Somerset, UK: Haynes. ISBN 978-1-85260-308-3.

- Brickhill, Paul. The Dam Busters: An Account of 617 Squadron, R.A.F., 1943–45, with plates. London: Evans Bros., 1951. "Novelised" style. Covers entire wartime story of 617 Squadron. OCLC 771295878

- Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War, Volume IV: The Hinge of Fate. 2nd edition. London: Cassell, 1951. OCLC 978145234

- Cockell, Charles S. "The Science and Scientific Legacy of Operation Chastise." Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 27, 2002, pp. 278–286. ISSN 0308-0188

- Dildy, Douglas C. Dambusters: Operation Chastise, Osprey Raid Series No. 16. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84603-934-8.

- Falconer, Jonathan. The Dam Busters Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7509-4758-9.

- Gibson, Guy. Enemy Coast Ahead. London: Pan Books, 1955. Gibson's own account. OCLC 2947593

- Hastings, Max. Operation Chastise: The RAF's Most Brilliant Attack of World War II. HarperCollins, New York, 2020. ISBN 978-0-06-295363-6

- Holland, James (2012). Dam Busters: The race to smash the dams 1943. London: Bantam (Transworld). ISBN 978-0593-0667-68.

- Nichol, John (2015). After the Flood: What the Dambusters did next. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-810031-5.

- Robertson, J. H. The Story of the Telephone: A History of the Telecommunications Industry of Britain. London: Pitman & Sons Ltd., 1947. OCLC 930475400

- Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich: Memoirs. London: Cassell, 1999, First Edition 1970. (Translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston; originally published in German as Erinnerungen [Recollections], Propyläen/Ullstein, 1969.) ISBN 978-0-684-82949-4.

- Sweetman, John. Operation Chastise. London: Jane's, 1982. ISBN 978-0-86720-557-2.

- Sweetman, John. The Dambusters Raid. London: Cassell, 1999. ISBN 978-0-304-35173-2.

- Ward, Chris; Lee, Andy; Wachtel, Andreas (2008) [2003]. Dambusters: The definitive history of 617 Squadron at war 1943-1945 (2 ed.). Surrey, UK: Red Kite. ISBN 978-0-9554735-3-1.

External links

- The Dams Raid with context

- Official site of the Royal Air Force about Operation Chastise Archived 5-April-2017

- Dambusters site with details of Operation Chastise including video footage and more

- Online Dambusters exhibition at the UK National Archives

- BBC Online – Myths and Legends – Home of the Dambusters

- 60th Anniversary BBC News.

- "Fly-past marks Dambusters anniversary" (photographs), Daily Telegraph, 16 May 2008.

- German history website about Operation Chastise (in German)

- G for George at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra

- German photography archive (in German)

- Website about Flt Lt David Maltby and his crew

- Dambusters weblog

- List of all 133 aircrew who took part in Operation Chastise

- 20 Historical Photographs from Operation Chastise

- Allied Psychological Warfare to Capitalise on the Dambusters Raid Archived 20 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Dambusters site of Dambusters Museum Germany (in German)

- Operation Chastise

- Aerial operations and battles of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Battles and operations of World War II involving Australia

- Battles of World War II involving Canada

- Battles and operations of World War II involving New Zealand

- History of the Royal Air Force during World War II

- Conflicts in 1943

- 1943 in Germany

- May 1943 events in Europe

![Plaque on the monument to the German victims of the bombing of the Möhne dam, called there the "Möhne catastrophe" [de]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/Wickede_%28Ruhr%29-8348.jpg/133px-Wickede_%28Ruhr%29-8348.jpg)