Old City (Bern)

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Bern's old city as seen from across the Aare | |

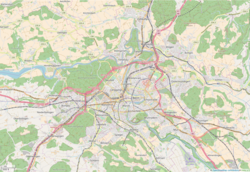

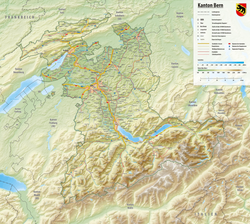

| Location | Bern, Bern-Mittelland, Canton of Bern, Switzerland |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 267 |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

| Area | 84.684 ha (209.26 acres) |

| Coordinates | 46°56′53″N 7°27′1″E / 46.94806°N 7.45028°E |

The Old City (German: Altstadt) is the medieval city center of Bern, Switzerland. Built on a narrow hill bordered on three sides by the river Aare, its compact layout has remained essentially unchanged since its construction during the twelfth to the fifteenth century. Despite a major fire in 1405, after which much of the city was rebuilt in sandstone, and substantial construction efforts in the eighteenth century, Bern's old city has retained its medieval character.

The Old City is home to Switzerland's tallest minster as well as other churches, bridges and a large collection of Renaissance fountains. In addition to many historical buildings, the seats of the federal, cantonal and municipal government are also situated in the Old City. It is a UNESCO Cultural World Heritage Site since 1983 due to the compact and generally intact medieval core and is an excellent example of incorporating the modern world into a medieval city. Numerous buildings in the Old City have been designated as Swiss Cultural Properties of National Significance, as well as the entire Old City.[1]

History

[edit]

The earliest settlements in the valley of the Aare date back to the Neolithic period. During the second century BC, the valley was settled by the Helvetii. Following the Roman conquest of Helvetia, a small Roman settlement was established near the Old City. This settlement was abandoned during the second century AD. From that time until the founding of Bern the area remained sparsely settled.

Founding

[edit]

The history of the city of Bern proper begins with its founding by Duke Berchtold V of Zähringen in 1191. Local legend has it that the duke vowed to name the city after the first animal he met on the hunt, which turned out to be a bear.[2] Both the name of the city (Bern can stand for Bär(e) n, bears) and its heraldic beast, come from this legend. At that time, much of today's Switzerland (then considered part of southern Burgundy) was under the authority of the house of Zähringen. The Zähringer leaders, although with no actual duchy of their own, were styled dukes by decree of the German king and exercised imperial power south of the Rhine. To establish their position there, they founded or expanded numerous settlements, including Fribourg (in 1157), Bern, Burgdorf and Morat.[3]

The area chosen by Berchtold V was a hilly peninsula bounded by the Aare on three sides. This location made the city easy to defend and influenced the later development of the city. The long, narrow shape of the peninsula made the city develop as several long, parallel rows of houses. The only major cross streets (going north and south) developed along the city walls, which were moved to allow the city to expand. Therefore, the cross streets mark the stages of development in the Old City of Bern.

On the eastern end of the peninsula a small fort, called Castle Nydegg, was founded by Berchtold IV in the second half of the twelfth century. Either when the fort was built or in 1191, the city of Bern was founded around the eastern end of the peninsula.[4]

First expansion – 1191

[edit]The first expansion of Bern occurred as the city was founded. Most likely the first city started at Nydegg Castle and reached to the Zytglogge (Swiss German: clock tower). The city was divided by three longitudinal streets, which stretched from the Castle to the city wall. Both the position of the town church and the shape of the eaves were typical for a Zähringer city.[4]

During the first half of the thirteenth century two additional streets (Brunngasse and Herrengasse) were added. Brunngasse was a semi-circular street on the north edge of the city, while Herrengasse was on the south side of the city. A wood bridge was built over the Aare which allowed increased trade and limited settlements on the east bank of the river.

Second expansion – 1255 to 1260

[edit]During the second half of the thirteenth century, the riverside foundation of Nydegg Castle was strengthened and connected to a new west city wall. This wall was added to protect the four streets, known as the New City or Savoy City, that had sprung up outside the Zytglogge. The new west wall included a gate known as the Käfigturm (German: Prison Tower).

Around 1268 Nydegg Castle was destroyed, and the city expanded into the area formerly occupied by the castle.[4] In the south-east part of the peninsula below the main hill that the rest of the Old City occupied, a section known as Matte grew up.

Third expansion – 1344 to 1346

[edit]For almost a century the Käfigturm remained the western boundary of Bern. However, as the city grew, people began settling outside the city walls. In 1344 the city started to build a third wall to protect the growing population. By 1346 the project was finished, and six new streets were protected by a wall and the Christoffelturm (German: St. Christopher Tower). The Christoffelturm remained the western border of Bern until the nineteenth century. From 1622 to 1634 a series of defensive walls and strong points were added outside the Christoffelturm. These defensive walls, known as the Grosse Schanze and Kleine Schanze (large and small redoubts respectively) as well as the Schanzegraben (redoubt ditch or moat), were never used as living space for the city, though the Schanzengraben was used for a while to house the Bärengraben.

Great Fire of 1405

[edit]

Bern was included in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites because of "an exceptionally coherent planning concept" and because "the medieval town...has retained its original character".[5] Bern owes its coherent planning concept and its famous arcades to a disaster. In 1405 a fire broke out in Bern, which was mostly wooden buildings at the time. The fire raced through the city and destroyed most of the buildings in town. In the wake of this disaster, the city was rebuilt with all stone houses in similar medieval styles. The arcades were added throughout the fifteenth century as houses expanded in the upper stories out into the street. Throughout the next three centuries houses were modified, but the essential elements (stone construction, arcades) remained.

In the sixteenth century, as Bern became a powerful and rich city-state, public fountains were added to Bern. A number of fountains were topped with large allegorical statues, eleven of which are still visible in the city. The fountains served to show the power and wealth of the city,[6] as well as providing fresh water for the citizens of the city. Overall, the city remained nearly unchanged for the next two centuries.

Expansion and destruction of the Christoffelturm

[edit]

By the early nineteenth century, Bern had expanded as far as it could within the old city walls. An increasing number of people were living outside the city walls in neighbouring communities. Throughout the nineteenth century, this ring of modern cities grew up around the Old City without forcing it to demolish the medieval city core. However, the growth around the Old City did lead to several projects.

Within the Old City of Bern, many of the old stone buildings were renovated without changing the outer appearance. The bell tower was finally finished on the Münster (German: Minister or Cathedral), making it the tallest church in Switzerland. A new bridge was built across the Aare at Nydegg in 1842 to 1844. The new bridge was larger than the, still standing, old bridge, called Untertorbrücke, which had been built in 1461 to 1487.

One of the biggest projects was the proposed destruction of the Christoffelturm to open up the west end of the city. Following a very close vote, the decision to remove the Christoffelturm and city wall was made on 15 December 1864. In the spring of the following year Gottlieb Ott led the team that removed the tower. Currently, the former location of the Christoffelturm is a large road interchange, a major bus station and the central train station.

Federal Capital in the twentieth century

[edit]

Following the Sonderbundskrieg (German: Separate Alliance War) in 1847, Switzerland established a federal constitution and Bern was chosen as the capital of the new Federal State. The vote to make Bern the federal city was met with little enthusiasm (419 vs 313 votes) in Bern[7] due to concerns over the cost. The first Bundesrathaus or Parliament House was built in 1852–1857 by the city of Bern in a New-Renaissance style. The mirror image Bundeshaus Ost (East Federal Building) was built in 1884–1892. Then, in 1894–1902 the domed Parlamentsgebäude or Parliament Building was built between the other two buildings.[8] The three parliament buildings represent the majority of the new, federal construction in the Old City. Most of the other buildings that come with a national capital were placed outside the Old City or were incorporated into existing buildings.

For centuries the famous Bärengraben (German: Bear Pits) were located in the Old City. According to the Bernese historian Valerius Anshelm, the first bears were kept on Bärenplatz (German: Bears' Plaza) in 1513.[2] They were moved from the modern Bärenplatz to the Schanzengraben near the former Christoffelturm in 1764. However, the bears remained in the Old City until the expansion of the new capital forced them out. The bears and the Bärengraben were moved from the Old City across the Aare on 27 May 1857.[2]

In the twentieth century, Bern has had to deal with incorporating the modern world into a medieval city. The plaza where the Christoffelturm used to be, has become the central bus stop for the city. The main train station was built under the plaza, and actually includes some of the foundations from the Christoffelturm and wall in the train station. However, one of the biggest challenges has been integrating automobile traffic into the Old City. Due to the number of important buildings in the Old City and the central location of the Old City, it was impossible to completely close off this area to vehicles. While some streets have remained pedestrian zones, most major streets carry city buses, trams or personal vehicles.

Districts and neighbourhoods

[edit]

The old city was historically subdivided into four Viertel and four Quartiere. The Viertel were the city's official administrative districts. They were instituted for tax and defence purposes in the thirteenth century and ceased to be used in 1798 after the fall of the Ancien Régime in Bern.[9]

Of greater practical importance were the Quartiere, the four traditional neighbourhoods in which people of similar social and economic rank congregated. They emerged in the late Middle Ages, overlap the Viertel boundaries and remain easily identifiable in today's cityscape.[9]

The central and oldest neighbourhood is the Zähringerstadt (Zähringer town), which contained the medieval city's principal political, economic and spiritual institutions. These were strictly separated: official buildings were situated around the Kreuzgasse (Cross Alley), ecclesiastical buildings were located at the Münstergasse (Cathedral Alley) and Herrengasse (Lords' Alley), while guilds and merchants' shops clustered around the central Kramgasse (Grocers Alley) and Gerechtigkeitsgasse (Justice Alley).[10] Junkerngasse (Junker Lane), which is parallel to Gerechtigkeitsgasse, was originally known as Kilchgasse (Church Lane) but was renamed because of number of patricians or untitled nobility which lived on the southern side of the peninsula.

The second oldest neighbourhood, the Innere Neustadt ('Inner New City'), was built during the city's first westward expansion in 1255, between the first western wall guarded by the Zytglogge tower and the second wall, guarded by the Käfigturm. Its central feature is the broad Marktgasse (Market Alley).

Situated in the northeast and southeast of the Aare peninsula, the Nydeggstalden and the Mattequartier together constitute medieval Bern's smallest neighbourhood. Workshops and mercantile activity prevailed in this area, and medieval sources tell of numerous complaints about the ceaseless and apparently nerve-wracking noise of machinery, carts and commerce. The Matte area at the riverside features three artificial channels, through which Aare water was diverted to power three city-owned watermills built in 1360.[11] In the early twentieth century, a small hydroelectric plant was built in that location. Nearby, the busy Schiffländte (ship landing-place) allowed for the reloading of goods transported by boat up and down the river.[12]

The last neighbourhood to be built was the Äussere Neustadt ('Outer New City'), which added a third and final layer to Bern's defences starting in 1343. All of these walls, gates and earthworks were demolished in the nineteenth century ending with the destruction of Bern's greatest of its three guard towers, the Christoffelturm. Only the four central streets were lined with residential houses in late medieval times, while the rest of the area was devoted to agriculture and animal husbandry.[13]

Significant buildings

[edit]While the entire old town of Bern is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, there are a number of buildings and fountains within the city that merit special mention. All of these buildings are also listed in the Swiss Inventory of Cultural Property of National and Regional Significance.[1]

Münster (Cathedral)

[edit]

The Münster of Bern (German: Berner Münster) is a Protestant Gothic cathedral located on the south side of the peninsula. Construction on the Münster began in 1421 and finished with the bell tower in 1893. The bell tower is 100 m (328 ft) and is the tallest in Switzerland. The largest bell in the bell tower is also the largest bell in Switzerland. This enormous bell, weighing about 10 tons and 247 cm (8.1 ft) in diameter,[14] was cast in 1611 and is still rung every day. It is possible to stand next to the bell when it is rung, but one has to cover one's ears to avoid hearing damage.

Above the main portal is a rare complete collection of Gothic sculpture. The collection represents the Christian belief in the Last Judgment where the wicked will be separated from the righteous. The large 47 free-standing statues are replicas (the originals are in the Bern History Museum) and the 170 smaller statues are all original.

The interior is large, open and fairly empty. Nearly all the art and altars in the cathedral were removed in 1528 during the iconoclasm of the Protestant Reformation. The paintings and statues were dumped in what became the Cathedral Terrace, making the terrace a rich archaeological site. The only major pieces of art that survived the iconoclasm inside the cathedral are the stained-glass windows and the choir stalls.

The stained-glass windows date from 1441–1450 and are considered the most valuable in Switzerland.[15] The windows include a number of heraldic symbols and religious images as well as an entire "Dance of Death" window. This window shows death, as a skeleton, claiming people from all professions and social classes. A "Dance of Death" was intended as a reminder that death would come to everyone regardless of wealth or status and may have been a comfort in a world filled with plagues and wars.

The choir, in the eastern side of the Cathedral between the nave and the sanctuary, houses the first Renaissance choir stalls in Switzerland.[16] The stalls are carved with lifelike animals and images of daily life.

Zytglogge

[edit]

The Zytglogge is the landmark medieval clock tower in the Old City of Bern. It has existed since about 1218–1220[17] and is one of the most recognisable symbols of Bern. The name Zyglogge is Bernese German and translates as Zeitglocke in Standard German or time bell in English. A "time bell" was one of the earliest public timekeeping devices, consisting of a clockwork connected to a hammer that rang a small bell at every full hour.[18] The Zytglogge clock is one of the three oldest clocks in Switzerland.[19]

Following the first expansion of Bern, the Zytglogge was the gate tower of the western fortifications. At this time, it was a squat tower of only about 16 m (52 ft) in height which was open in the back.[19] During the second expansion, to the Käfigturm, the Zytglogge wall was removed, and the tower was relegated to second-line status. Around 1270–1275 an additional 7 m (23 ft) was added to the tower to allow it to overlook the surrounding houses.[18] After the third expansion, to the Christoffelturm, the Zytglogge was converted into a women's prison. Most commonly it was used to house Pfaddendirnen – "priests' whores", women convicted of sexual relations with clerics.[20] At this time, the Zytglogge also received its first slanted roof.[21]

In the Great Fire of 1405, the tower was completely burned out. The structural damage would not be completely repaired until 1983. The prison cells were abandoned[22] and a clock was installed above the gate. This clock, together with a bell cast in 1405, gave the tower the name of Zytglogge. In the late fifteenth century the tower was decorated with four decorative corner towerlets and heraldic symbols.[23] The astronomical clock was extended to its current state in 1527–1530. In addition to the astronomical clock, the Zytglogge features a group of mechanical figures. At three minutes before the hour the figures which include a rooster, a fool, a knight, a piper, a lion and bears, put on a show.[24] The animals chase each other around, the fool rings his bells and the rooster caws. During the day it is common to see small crowds gathered around the foot of the Zytglogge waiting for the show to start.

The Zytglogge's exterior was repainted by Gotthard Ringgli and Kaspar Haldenstein in 1607–10, who introduced the large clock faces that now dominate the east and west façades of the tower.[22] The corner towerlets were removed again sometime before 1603.[25] In 1770–71, the Zytglogge was renovated by Niklaus Hebler and Ludwig Emanuel Zehnder, who refurbished the structure in order to suit the tastes of the late Baroque, giving the tower its contemporary outline.[26]

Both façades were again repainted in the Rococo style by Rudolf von Steiger in 1890. The idealising historicism of the design came to be disliked in the twentieth century, and a 1929 competition produced the façade designs visible today: on the west façade, Victor Surbek's fresco "Beginning of Time" and on the east façade, a reconstruction of the 1770 design by Kurt Indermühle.[26] In 1981–83, the Zytglogge was thoroughly renovated again and generally restored to its 1770 appearance.[27]

Parliament buildings

[edit]

The Parliament Building (German: Bundeshaus, French: Palais fédéral, Italian: Palazzo federale, Latin: Curia Confoederationis Helveticae) is built along the southern edge of the peninsula and straddles the location of the former Käfigturm wall. The building is the used by both the Swiss Federal Council or Executive and Parliament or Federal Assembly of Switzerland. The complex includes the Bundeshaus West (built in 1852–57), the central Parliament Building (built in 1894–1902) and the Bundeshaus East (built in 1884–1892).[8] The central plaza in front of the Parliament building was built into a fountain in 2004. The plaza was paved with granite slabs and 26 water jets, one for each canton, were hidden under the plaza. The design of the plaza has won two international awards.[28]

The central Parliament Building was built to be visible and is topped with several large copper domes. The interior was decorated by 38 artists from every corner of the country. Three major themes tied all the works together. The first theme, national history, is represented by events and persons from Swiss history. This includes the Rütlischwur or the foundation of Switzerland in 1291 and figures such as William Tell, Arnold von Winkelried and Nicholas of Flüe. The second theme is the fundamental principles that Switzerland was founded on; including independence, freedom, separation of government powers, order and security. The final theme is the cultural and material variety of Switzerland; including politically (represented by Canton flags), geographically and socially.[8]

The two chambers where the National Council and the Council of States meet are separated by the Hall of the Dome. The dome itself has an external height of 64 m, and an internal height of 33 m. The mosaic in the center represents the Federal coat of arms along with the Latin motto Unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno (One for all, and all for one), surrounded by the coat of arms of the 22 cantons that existed in 1902. The coat of arms of the Canton of Jura, created in 1979, was placed outside of the mosaic.

Untertorbrücke

[edit]

The Untertorbrücke (German: Lower Gate bridge) is the oldest bridge in Bern still in existence. The original bridge, most likely a wooden walkway, was built in 1256 and spanned the Aare at the Nydegg Fortress. The bridge was destroyed in a flood in 1460. Within one year, construction began on a new stone bridge. The small Mariakapelle (Mary's Chapel) located in the side of the bridge column on the city side was blessed in 1467. However, the bridge wasn't finished until 1490. The new bridge was 52 meters (171 ft) long with the three arches spanning 13.5 m (44 ft), 15.6 m (51 ft) and 13.9 m (46 ft).[29] The bridge was modified several times including the removal of the stone guard rails which were replaced with iron rails in 1818–19.[29]

Until the construction of the Nydeggbrücke in 1840, the Untertorbrücke was the only bridge crossing the Aare near Bern. See List of Aare bridges in Bern.

Nydegg Church

[edit]

The original Nydegg Castle was built around 1190 by either Duke Berchtold V. von Zähringen[30] or his father Berchtold IV.[31] as part of the city defenses. Following the second expansion, the castle was destroyed by the citizens of Bern in 1268. The castle was located about where the Choir of the church now stands, with the church tower resting on the southern corner of the donjon.[32]

From 1341 to 1346 a church with a small steeple was built on the ruins of the castle. Then, between 1480 and 1483 a tower was added to the church. The central nave was rebuilt in 1493 to 1504. In 1529, following the Reformation, the Nydegg Church was used as a warehouse for wood and grain. Later, in 1566, the church was again used for religious services and in 1721 was placed under the Münster.

Holy Ghost Church

[edit]

The Holy Ghost Church (German: Heiliggeistkirche) is a Swiss Reformed Church at Spitalgasse 44. It is one of largest Swiss Reformed churches in Switzerland. The first church was a chapel built for the Holy Ghost hospital and abbey. The chapel, hospital and abbey were first mentioned in 1228 and at the time sat about 150 meters (490 ft) outside the western gate of the first city wall. This building was replaced by the second church between 1482 and 1496. In 1528 the church was secularized by the reformers and the last two monks at the Abbey were driven out of Bern.[33] During the following years it was used as a granary. In 1604 it was again used for religious services, as the hospital church for the Oberer Spital. The second church was demolished in 1726 to make way for a new church building, which was built in 1726–29 by Niklaus Schiltknecht.[34]

The first organ in the new church was installed in 1804 and was replaced in 1933 by the second organ. The church has six bells, one of the two largest was cast in 1596 and the other in 1728. The four other bells were all cast in 1860.[35] The interior is supported by 14 monolithic columns made of sandstone and has a free-standing pulpit in the northern part of the nave. Much like the St. Pierre Cathedral in Geneva, the Church of the Holy Ghost holds about 2,000 people and is one of the largest Protestant churches in Switzerland.[35]

From 1693 to 1698 the hospital's chief minister was the Pietist theologian, Samuel Heinrich König. In 1829 and 1830, the vicar of the church was the poet Jeremias Gotthelf.

Fountains

[edit]There are over 100 public fountains in the city of Bern of which eleven are crowned with Renaissance allegorical statues.[6] The statues were created during the period of civic improvement that occurred as Bern became a major city-state during the sixteenth century. The fountains were originally built as a public water supply. As Bern grew in power, the original fountains were expanded and decorated but retained their original purpose.

Nearly all the sixteenth-century fountains, except the Zähringer fountain which was created by Hans Hiltbrand, are the work of the Fribourg master Hans Gieng:

-

The Läufer (Runner) Fountain

-

Justice fountain

-

Vennerbrunnen

-

Moses with the Ten Commandments

-

The Zähringer fountain with Zytglogge in the background

-

The Ogre has a sack of children waiting to be devoured

-

Statue of Anna Seiler, founder of Bern's hospital in 1354

From east to west, the first fountain is the Läuferbrunnen (German: Runner fountain) near the Nydegg Church on Nydeggstalden. The trough was built in 1824, but the figure dates from 1545.[36] The Runner has moved several times since its creation, and until about 1663 was known as the Brunnen beim unteren Tor (Fountain by the lower gate). Originally the Läuferbrunnen had an octagonal trough and a tall, round column. The trough was replaced with a rectangular trough before 1757[37] which was replaced in 1824. The round column was replaced with the current square limestone pillar in the eighteenth or nineteenth century.

The next fountain is the Gerechtigkeitsbrunnen (German:Justice fountain) on Gerechtigkeitsgasse. Built in 1543 by Hans Gieng, the fountain is topped with a representation of Justice. She stands with her eyes and ears bound, a sword of truth one hand and the scales in the other. On the pillar below her feet are four figures: the Pope, a Sultan, the Kaiser or Emperor and the Schultheiß or Lord Mayor. This represents the power of Justice over the rulers and political systems of the day; Theocracy, Monarchy, Autocracy and the Republic.[36]

The statue has been widely copied in towns throughout Switzerland. Currently, eleven "fountains of Justice" remain in Switzerland, and several others have probably been destroyed.[38] Direct copies exist in Solothurn (1561), Lausanne (1585), Boudry, Cudrefin and Neuchâtel; designs influenced by the Bernese statue are found in Aarau (1643), Biel, Burgdorf, Brugg, Zürich and Luzern.[39]

The Vennerbrunnen (German: Banner Carrier or Vexillum) is located in front of the old city hall or Rathaus. The Venner was military-political title in medieval Switzerland. He was responsible for peace and protection in a section of a city and then to lead troops from that section in battle. In Bern, the Venner was a very powerful position and was key in city's operations. Each Venner was connected to a guild and chosen from the guild. Venner was one of only two positions from which the Schultheiß or Lord Mayor was chosen.[40] The statue, built in 1542 shows a Venner in full armour with his banner.[36]

The Moses fountain, located on Münsterplatz (German: Cathedral Plaza) was rebuilt in 1790–1791. The Louis XVI style basin was designed by Niklaus Sprüngli. The Moses figure dates from the sixteenth century. The statue represents Moses bringing the Ten Commandments to the Tribes of Israel.[36] Moses is portrayed with two rays of light projecting from his head, which represent Exodus 34:29–35 which tells that after meeting with God the skin of Moses' face became radiant. The twin rays of light come from one longstanding tradition that Moses instead grew horns.

This is derived from a misinterpretation of the Hebrew phrase karan `ohr panav (קָרַן עֹור פָּנָיו). The root קרן Q-R-N (qoph, resh, nun) may be read as either "horn" or "ray of light", depending on vocalization. `Ohr panahv (עֹור פָּנָיו) translates to "the skin of his face".[41]

Interpreted correctly, these two words form an expression meaning that Moses was enlightened, that "the skin of his face shone" (as with a gloriole), as the KJV has it.[41]

The Septuagint properly translates the Hebrew phrase as δεδόξασται ἡ ὄψις, "his face was glorified"; but Jerome translated the phrase into Latin as cornuta esset facies sua "his face was horned".[41]

With apparent Biblical authority, and the added convenience of giving Moses a unique and easily identifiable visual attribute (something the other Old Testament prophets notably lacked), it remained standard in Western art to depict Moses with small horns until well after the mistranslation was realized by the Renaissance. In this depiction of Moses, the error has been identified but the artist has chosen to place horns of light on Moses' head to aid in identification.

The Simsonbrunnen or Samson fountain represents the Biblical story of Samson killing a lion found in Judges 14:5–20. According to the story, Samson was born to a sterile Israelite couple on the conditions that his mother and her child (Samson) abstain from all Alcohol and that he never shave nor cut his hair. Because of his commitment to living under these conditions, Samson is granted great strength. As a young man, he falls in love with a Philistine woman and decides to marry her. At this time, the Philistines ruled over the Israelites and Samson's decision to marry one causes great concern among his family. He calms their concerns and travels to marry his love. On the way, he is attacked by the lion and with his incredible strength kills the lion. Later, he sees that bees have built a honeycomb in the lion's body. He uses this event as the basis of a riddle, which when not answered, gives him the pretext to attack the Philistines and lead an unsuccessful rebellion. The fountain, built in 1544 by Hans Gieng, is modeled after the Simsonbrunnen in Solothurn.[36]

The Zähringerbrunnen was built in 1535 as a memorial to the founder of Bern, Berchtold von Zähringer. The statue is a bear in full armour, with another bear cub at his feet. The bear represents the bear, that according to legend, Berchtold shot on the Aare peninsula as he was searching for a site to build a city.

One of the most interesting statues is the Kindlifresserbrunnen (Bernese German: Child Eater Fountain but often translated Ogre Fountain) which is located on Kornhausplatz. The fountain was built in 1545–46 on the site of a fifteenth-century wooden fountain. Originally known as Platzbrunnen (German: Plaza Fountain), the current name dates to 1666.[42] The statue is a seated giant or ogre swallowing a naked child. Several other children are visible in a sack at the figure's feet. There are several interpretations of what the statue represents;[43] including that it is a Jew with a pointed Jewish hat[44] or the Greek god Chronos. However, the most likely explanation is that the statue represents a Fastnacht figure that scares disobedient children.[45]

The Anna Seiler fountain, located at the upper end of Marktgasse memorializes the founder of the first hospital in Bern. Anna Seiler is represented by a woman in a blue dress, pouring water into a small dish. She stands on a pillar brought from the Roman town of Aventicum (modern Avenches). On 29 November 1354 in her will[46] she asked the city to help found a hospital in her house which today stands on Zeughausgasse. The hospital initially had 13 beds and 2 attendants[24] and was to be an ewiges Spital[46] or a perpetual hospital. When Anna died around 1360[47] the hospital was renamed the Seilerin Spital. In 1531 the hospital moved to the empty Dominican Order monastery St. Michaels Insel (St. Michael's Island) and was then known as the Inselspital, which still exists over 650 years after Anna Seiler founded it. The modern Inselspital has about 6,000 employees and treats about 220,000 individuals per year.[48]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b "Swiss Inventory of Cultural Property of National and Regional Significance" (PDF). 27 November 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c The Old Bärengraben Archived 10 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 April 2008 (in German)

- ^ Zähringen, von in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c Bern (Gemeinde) Section 1.4 in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage List Description of the Old City of Bern. Accessed 25 April 2008

- ^ a b City of Fountains, Bern Tourism Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 April 2008

- ^ Bern (Gemeinde) Section 3.2 in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c Bundeshaus (Parliament Building) in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b Roland Gerber. Der Stadtgrundriss – Spiegel der Gesellschaft. In: Ellen J. Beer, Norberto Gramaccini, Charlotte Gutscher-Schmid, Rainer C. Schwinges (eds.) (2003). Berns grosse Zeit. Berner Zeiten (in German). Bern: Schulverlag blmv and Stämpfli Verlag. p. 42. ISBN 3-906721-28-0.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gerber, at 44.

- ^ Gerber, at 46.

- ^ Gerber, ibid.

- ^ Gerber, at 47.

- ^ Official Church Website-The Bells Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 April 2008 (in German)

- ^ Benteliteam (1985). Bern in Colors. Wabern, CH: Benteli-Werd Verlags AG. p. 34. ISBN 3-7165-0407-6.

- ^ Official Church Website-Tourism Archived 6 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 April 2008 (in German)

- ^ Ueli Bellwald (1983). Der Zytglogge in Bern. Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-85782-341-1.

- ^ a b Markus Marti (2005). 600 Jahre Zytglogge Bern. Eine kleine Chronik der Zeitmessung. p. 19. ISBN 3-7272-1180-6.

- ^ a b Niklaus Flüeler, Lukas Gloor & Isabelle Rucki (1982). Kulturführer Schweiz. Zürich: Ex Libris Verlag AG. pp. 68–73.

- ^ Clare O'Dea (8 October 2005). "Time marches on at the Zytglogge". Swissinfo.

- ^ Bellwald, 4.

- ^ a b Hofer, Paul (1952). Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Bern, Band 1: Die Stadt Bern (in German). Basel: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte. p. 107. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ^ Hofer, 107

- ^ a b Zurkinden (1983). Aral Auto-Reisebuch: Schweiz (in German). Zurich, CH: Ringier AG. pp. 222–224. ISBN 3-85859-179-3.

- ^ Hofer, 108.

- ^ a b Bellwald, 9.

- ^ Bellwald, 13.

- ^ Swiss World.org website accessed 25 April 2008.

- ^ a b Weber, Berchtold (1976). "Untertorbrücke". Historic-topographic Lexicon of Berne (in German). Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ Hofer, Paul; Luc Mojon (1969). Band 5: Die Kirchen der Stadt Bern (in German). Basel: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte. pp. 233–234. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ History of the Nydegg Church, from the church website Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine pg 27, accessed 28 April 2009 (in German)

- ^ History of the Nydegg Church, from the church website Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine pg 28, accessed 28 April 2009 (in German)

- ^ Historische Notizen zur Heiliggeistkirche, A. 5., G.2., F.4., F.2., Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ Paul Hofer und Luc Mojon; Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Bern Band V, die Kirchen der Stadt Bern Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine 58. Band der Reihe Die Kunstdenkmäler der Schweiz, Birkhäuser Basel 1969

ISBNSeiten 157–232 - ^ a b Weber, Berchtold (1976). Historisch-topographisches Lexikon der Stadt Bern. Archived from the original on 6 September 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2010.(in German)

- ^ a b c d e Flüeler (1982). Kulturführer Schweiz. Zurich, CH: Ex Libris Verlag AG. pp. 72–73.

- ^ "Hofer, 323". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ^ Hofer, 321.

- ^ Hofer, 319.

- ^ Venner in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c Moses horns Archived 4 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 April 2008

- ^ Weber, Berchtold (1976). "Kindlifresserbrunnen". Historic-topographic Lexicon of Berne (in German). Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ City Council of Bern minutes of the 14 May 1998 5:00PM session accessed 23 November 2008(in German)

- ^ Switzerland is yours.com travel guide accessed 25 April 2008

- ^ "Hofer, 281". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ^ a b Copy of Anna Seiler's will, translated into modern German Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 April 2008 (in German)

- ^ Inselspital website-History accessed 25 April 2008 (in German)

- ^ Inselspital website-Home Page accessed 25 April 2008 (in German)

External links

[edit]- Official UNESCO listing for Old City of Bern

- UNESCO Evaluation of the Old City of Bern (PDF)

- Tourist Office of the city of Bern (archived 27 September 2007)

- The Website of the Clock Tower (Zytglogge) (in English and German)

- Lists of Swiss Inventory of Cultural Property of National and Regional Significance for Every Canton (archived 7 January 2017)