History of Kentucky

This article's lead section may be too long. (December 2023) |

| History of Kentucky |

|---|

|

|

|

The prehistory and history of Kentucky span thousands of years, and have been influenced by the state's diverse geography and central location. Archaeological evidence of human occupation in Kentucky begins approximately 9,500 BCE. A gradual transition began from a hunter-gatherer economy to agriculture c. 1800 BCE. Around 900 CE, the Mississippian culture took root in western and central Kentucky; the Fort Ancient culture appeared in eastern Kentucky. Although they had many similarities, the Fort Ancient culture lacked the Mississippian's distinctive, ceremonial earthen mounds.

The first Europeans to visit Kentucky arrived in the late 17th century via the Ohio River from the northeast, and later, in the late 18th century, from the southeast through natural passes in the Appalachian Mountains. Early Settlers pursuant to the Treaty of Fort Stanwix 1768, came into conflict with the Shawnee, Cherokee and other tribes in their south of Ohio hunting grounds. This launched Lord Dunmore's war in 1774, and during the Revolution, it became the Cherokee-American Wars that lasted until after statehood. A series of county divisions of Virginia Colony west of the Appalachians resulted in Kentucke County in 1777, the District of Kentucky, and finally its admission into the Union as the 15th state on June 1, 1792.

The early economy rested on family farms and traditional southern plantations in the central and western parts of the state, with a rapid growth in tobacco for the national market. Until 1865, slavery played a significant role and was a backbone in Kentucky's economy and politics. The state remained a border state during the Civil War, with both Union and Confederate sympathizers as well as split state governments with 68 of 110 counties or half of Kentucky sending delegates to the Russellville Convention, signing an ordinance of secession creating the Confederate government of Kentucky and joining the Confederacy on December 10, 1861, and making Bowling Green the capital. The issue of slavery ultimately led to the state's split between the Union and Confederacy with most Kentuckians deeply supporting the institution and Southern rights while also having split conditional Southern Unionist sentiments. While the Confederacy controlled more than half of Kentucky early in the war. Union forces controlled the state during the remainder of the war after 1862. Slavery was abolished by the 13th Amendment in late 1865. Following the Civil War, Kentucky underwent a period of Reconstruction, during which the state's political and social structures were reshaped to reflect the post-war era. Black people gained the right to vote in Kentucky and never lost the right.

Kentucky has a long and complicated history of feuds, especially in the mountains. They were rooted in political, economic, and social tensions. Violence climaxed with the assassination of Governor William Goebel in 1900. Industrialization rose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the coal mining and manufacturing industries playing a significant role in the state's economy.

In 1919, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect, prohibiting the sale and consumption of alcohol. Kentucky, a major producer of bourbon and other distilled spirits, saw significant social and economic changes as a result, with moonshining in the mountains to provide liquor for the cities to the north.

The mid-20th century saw significant civil rights struggles in Kentucky and across the United States, with activists fighting for equal rights for African Americans and other marginalized groups. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, environmental issues have become increasingly important in Kentucky. Especially important are concerns over the coal mining industry's impact on the environment and public health leading to political and social changes. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen significant economic changes as globalization has become a major force in the American and global economies. Also in the 21st century, Kentucky has seen a significant increase in immigration, leading to demographic changes and debates over immigration policy.

Etymology and nickname

The etymology of "Kentucky" or "Kentucke" is uncertain. One suggestion is that it is derived from an Iroquois name meaning "land of tomorrow".[1] According to Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia, "Various authors have offered a number of opinions concerning the word's meaning: the Iroquois word kentake meaning 'meadow land', the Wyandotte (or perhaps Cherokee or Iroquois) word ken-tah-the meaning 'land of tomorrow', the Algonquian term kin-athiki referring to a river bottom, a Shawnee word meaning 'at the head of a river', or an Indian word meaning land of 'cane and turkeys'".[2] Kentucky's nickname, the "Bluegrass State", derives from the imported grass grown in the central part of the state; "The nickname also recognizes the role that the Bluegrass region has played in Kentucky's economy and history."[3]

Pre-European habitation and culture

Paleo-Indian era (9500 – 7500 BCE)

Based on evidence in other regions, humans were probably living in Kentucky before 10,000 BCE; however, archaeological evidence of their occupation has not yet been documented.[4] Stone tools, particularly projectile points (arrowheads) and scrapers, are primary evidence of the earliest human activity in the Americas. Paleo-Indian bands probably moved their camps several times per year. Their camps were typically small, consisting of 20 to 50 people. Band organization was egalitarian, with no formal leaders and no social ranking or classes. Linguistic, blood-type and molecular evidence, such as DNA, indicate that indigenous Americans are descendants of east Siberian peoples.

At the end of the last ice age, between 8000 and 7000 BCE, Kentucky's climate stabilized; this led to population growth, and technological advances resulted in a more sedentary lifestyle. The warming trend killed Pleistocene megafauna such as the mammoth, mastodon, giant beavers, tapirs, short-faced bear, giant ground sloths, saber-toothed tiger, horse, bison, muskox, stag-moose, and peccary. All were native to Kentucky during the ice age, and became extinct or moved north as the ice sheet retreated.[5]

No skeletal remains of Paleo-Indians have been found in Kentucky. Although many Paleo-Indian Clovis points have been discovered, there is little evidence at Big Bone Lick State Park that they hunted mastodons.[4]

The radiocarbon evidence indicates that mastodons and Clovis people overlapped in time; however, other than one fossil with a possible cut mark and Clovis artifacts that are physically associated with but dispersed within the bone-bearing deposits, there is no incontrovertible evidence that humans hunted Mammut americanum at the site.[6]

Archaic period (7500 – 1000 BCE)

The extinction of large game animals at the end of the ice age changed the area's culture by 7500 BCE. By 4000 BCE, the people of Kentucky exploited native wetlands. Large shell middens (trash piles, ancient landfills) are evidence of clam and mussel consumption.[citation needed] Although middens have been found along rivers, there is limited evidence of riverbank Archaic occupation before 3000 BCE. Archaic Kentucky natives' social groups were small: a few cooperating families. Large shell middens, artifact caches, human and dog burials, and burnt-clay flooring indicate permanent Archaic settlements. White-tailed deer, mussels, fish, oysters, turtles, and elk were significant food sources.

Natives developed the atlatl, which launched spears faster. Other Archaic tools were grooved axes, conical and cylindrical pestles, bone awls, cannel coal beads, hammerstones, and bannerstones. "Hominy holes" – depressions in sandstone made by the grinding of hickory nuts or seed to make them easier to use for food – were also used.[7]

People buried their dogs in shell (mussel) mound sites along the Green and Cumberland Rivers.[8] At the Indian Knoll site, 67,000 artifacts have been uncovered; they include 4,000 projectile points and twenty-three dog burials, seventeen of which are well-preserved. Some dogs were buried alone; others were buried with their masters, with adults (male and female), or with children. Archaic dogs were medium-sized, about 14–18 inches (36–46 cm) tall at the shoulder, and were probably related to the wolf. Dogs had a special place in the lives of Archaic and historic indigenous peoples. The Cherokee believed that dogs were spiritual, moral and sacred, and the Yuchi (a tribe who lived near the Green River) may have shared that belief.

The Indian Knoll site, along the Green River in Ohio County, is over 5,000 years old. Although evidence of earlier settlement exists, the area was most densely settled from c. 3000 to 2000 BCE (when the climate and vegetation neared modern conditions). The Green River floodplain provided a stable environment, which supported agricultural development; nearby mussel beds facilitated permanent settlement. At the end of the Archaic period, natives had cultivated a form of squash for its edible seeds and use as a container.[9]

Woodland period (1000 BCE – 900 CE)

Native Americans began to cultivate several species of wild plants c. 1800 BCE, transitioning from a hunter-gatherer society to one based on agriculture. In Kentucky, the Woodland period followed the Archaic period and preceded the agricultural Mississippian culture. It was characterized by the development of shelter construction, stone and bone tools, textile manufacturing, leather crafting, and cultivation. Archaeologists have identified a distinct Middle Woodland cultures, Crab Orchard culture, in the western part of the state. The remains of two groups, the Adena (early Woodland) and the Hopewell (middle Woodland), have been found in present-day Louisville, in the central bluegrass region and northeastern Kentucky.[9]

The introduction of pottery, its widespread use, and the increased sophistication of its forms and decoration (first believed to have occurred around 1000 BCE) are major demarcations of the Woodland period. Archaic pots were thick, heavy, and fragile; Woodland pottery was more intricately designed and had more uses, such as cooking and storing surplus food. Woodland peoples also used baskets and gourds as containers.[10] Around 200 BCE, maize cultivation migrated to the eastern United States from Mexico. The introduction of corn changed Kentucky agriculture from growing indigenous plants to a maize-based economy. In addition to cultivating corn, the Woodland people also cultivated giant ragweeds, amaranth (pigweed), and maygrass.[10] The initial four plants known to have been domesticated were goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri), sunflower (Helianthus annuus var. macroscarpus), marsh elder (Iva annua var. macrocarpa), and squash (Cucurbita pepo ssp. ovifera). Woodland people grew tobacco, which they smoked ritually; they still used stone tools, especially for grinding nuts and seeds.[10] They mined Mammoth and Salts Caves for gypsum and mirabilite, a salty seasoning. Shellfish was still an important part of their diet, and the most common prey were white-tailed deer. They continued to make and use spears; late in the Woodland period, however, the straight bow became the weapon of choice in the eastern United States (evidenced by smaller arrowheads during this period).[10] In addition to bows and arrows, some southeastern Woodland peoples also used blowguns.

Between 450 and 100 BCE, Native Americans began to build earthen burial mounds.[9] The Woodland Indians buried their dead in conical (later flat or oval) burial mounds, which were often 10 to 20 feet (3.0–6.1 m) high. The Woodland people were called "Mound Builders" by 19th-century observers.[10]

The Eastern Agricultural Complex enabled Kentucky natives to change from a nomadic culture to living in permanent villages. They lived in bigger houses and larger communities,[10] although intensive agriculture only began with the Mississippian culture.

Mississippian culture (900 – 1600 CE)

Maize became highly productive c. 900 CE, and the Eastern Agricultural Complex was replaced by the Mississippian culture's maize-based agriculture. Native village life revolved around planting, growing and harvesting maize and beans, which made up 60 percent of their diet.[10] Stone and bone hoes were used by women for most cultivation. They grew the "Three Sisters" (maize, beans, and squash), which were planted together to complement each plant's characteristics. Beans climbed the cornstalks, and large squash leaves retained soil moisture and reduced weeds. White-tailed deer were the dominant game animals.[9] Mississippian culture pottery was more varied and elaborate than that of the Woodland period (including painting and decoration), and included bottles, plates, pans, jars, pipes, funnels, bowls, and colanders. Potters added handles to jars, attaching human and animal effigies to some bowls and bottles. Elite Mississippians lived in substantial, rectangular houses atop large platform mounds. Excavations of their houses revealed burned clay wall fragments, indicating that they decorated their walls with murals. They lived year-round in large communities, some of which had defensive palisades, which had been established for centuries. An average Fort Ancient or Mississippian town had about 2,000 inhabitants.[10] Some people lived on smaller farms and in hamlets. Larger towns, centered on mounds and plazas, were ceremonial and administrative centers; they were located near the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys and their tributaries: rivers with large floodplains.

A Mississippian culture developed in western Kentucky and the surrounding area, while a Fort Ancient culture dominated in the eastern portion of what became Kentucky. While the two cultures are similar in numerous ways, the Fort Ancient culture didn't have the temple mounds and chiefs' houses like the Mississippian culture had.[11]

Mississippian sites in western Kentucky are at Adams, Backusburg, Canton, Chambers, Jonathan Creek, McLeod's Bluff, Rowlandtown, Sassafras Ridge, Turk, Twin Mounds and Wickliffe. The Wickliffe Mounds, in western Kentucky, were inhabited from 1000 to 1350 CE; two large platform mounds and eight smaller mounds were distributed around a central plaza. Its inhabitants traded with those of North Carolina, Wisconsin, and the Gulf of Mexico. The Wickliffe community had a social hierarchy ruled by a hereditary chief. The Rowlandton Mound Site was inhabited from 1100 to 1350 CE. The 2.4-acre (0.97 ha) Rowlandton Mound Site has a large platform mound and an associated village area, similar to the Wickliffe Mounds; these settlements were probably established by Late Woodland peoples. The Tolu Site was inhabited by Kentucky natives from 1200 to 1450 CE. It originally had three mounds: a burial mound, a substructure platform mound, and another mound of unknown function. The site has a central plaza and a large, 6.6-foot-deep (2.0 m) midden. A rare Cahokia-made Missouri flint clay 7-inch (180 mm) human-effigy pipe was found at this site. The Marshall Site was inhabited from 900 to 1300 CE, and the Turk and Adams sites from 1100 to 1500. The Slack Farm, inhabited from 1400 to 1650, had a mound and a large village. One thousand or more people could have been buried at the site's seven cemeteries, and some were buried in stone box graves. Native Americans abandoned a large, late-Mississippian village at Petersburg which had at least two periods of habitation: 1150 and 1400 CE.[12]

The Mississippian period ends at about the time of the earliest French, Spanish, and English explorers. Seventeenth-century French explorers documented a number of tribes living in Kentucky until the Beaver Wars in the 1670s including the Cherokee (in southeastern Kentucky caves and along the Cumberland River); the Chickasaw, in the western Jackson Purchase area (especially along the Tennessee River); the Delaware (Lenape) and Mosopelea (at the mouth of the Cumberland River); the Shawnee (throughout the state), and the Wyandot and Yuchi (on the Green River).[13][14] Hunting bands of Iroquois, Illinois, Lenape and Miami also visited Kentucky.[15]

Beaver Wars and Iroquois dominance

This article is missing information about Beaver wars and Iroquois dominance. (May 2023) |

The Eskippakithiki Settlement 18th century

The archaeological evidence (or lack thereof) indicates that for 50 years following the Beaver Wars, there were no Native American settlements in Kentucky, until the appearance of Eskippakithiki. Historians do not think that singular settlement is part of a continuous Kentuckian Native American culture, but rather that it was transplanted from elsewhere, possibly a separatist band from one of the Shawnee towns along the Scioto River in Ohio, or a late Shawnee migration from eastern North Carolina.[citation needed]

Eskippakithiki (also known as Indian Old Fields), was Kentucky's last Native American (Shawnee) village,[16] in the eastern portion of present-day Clark County, in the north central portion of the state. The name translates as "place of blue licks", in reference to the salt licks nearby. It existed from 1718-1754. A 1736 French census reported Eskippakithiki's population as two hundred families.[17]

Eskippakithiki had a population of eight hundred to one thousand. The town was protected by a stout stockade some two hundred yards in diameter, and it was surrounded by three thousand five hundred acres (1,400 ha) of land that had been cleared for crops.[18]

John Finley, a compatriot of Daniel Boone, lived and traded in Eskippakithiki in 1752. Finley said that he was attacked by a party of 50 Christian Conewago and Ottawa Indians, a white French Canadian and renegade Dutchman Philip Philips (all from the St. Lawrence River) who were on a scalp-hunting expedition against southern tribes on January 28, 1753, on the Warrior's Path 25 miles (40 km) south of Eskippakithiki, near the head of Station Camp Creek in Estill County.[16] Major William Trent wrote a letter which first mentions "Kentucky" about the attack on Finley:

I have received a letter just now from Mr. Croghan, wherein he acquaints me that fifty-odd Ottawas, Conewagos, one Dutchman, and one of the Six Nations, that was their captain, met with some of our people at a place called Kentucky on this side Allegheny river, about one hundred and fifty miles (240 km) from the Lower Shawnee Town. They took eight prisoners, five belonging to Mr. Croghan and me, the others to Lowry; they took three or four hundred pounds worth of goods from us; one of them made his escape after he had been a prisoner three days. Three of John Findley's men are killed by the Little Pict Town, and no account of himself ... There was one Frenchman in the Company.

— Lucien Beckner[16]

Seven Pennsylvanian traders were in Finley's crew along with a Cherokee slave. The traders shot at the natives, who took them prisoner and brought them to Canada; some were then shipped to France as prisoners of war. Finley fled, and the next European who went to Eskippathiki found the town burned to the ground.[16]

French colonial period to 1763

Prior to 1763, all of trans-Appalachia including what was later to be known as Kentucke country (and much else besides) was part of Louisiana, an administrative district of New France. It was the first European claim on North American lands west of the Appalachians and south of the Great lakes. Two early pass-bys by Robert de la Salle at the Falls of the Ohio in 1669 (speculatively) and Marquette and Jolliet at the mouth of the Ohio on the Mississippi in 1673 are recorded.

On September 1, 1671, Thomas Batts (Thomas Batte), Thomas Wood, and Robert Fallam (Robert Hallom) set out on horse from Appomattox Town acting under a commission granted to Coloner Abraham Wood to explore the trans-Appalachian waterways. There is much ambiguity about the extent of their travels westward, but they are credited with discovering Wood's River (today the New River), a tributary of the Kanawha River. Some historians believe that their journey reached the basin of the Guyandotte River, or even that of the Tug Fork tributary of the Big Sandy River in extreme eastern Kentucky.[19] On account of Indian impatience, they returned to Fort Henry by Oct. 1. Later, the Kanawha River and by extension, the New River, and their environs would be considered part of south of Ohio lands known by the Native American name Kentucke.

English colonists Gabriel Arthur and James Needham were sent out by Abraham Wood from Fort Henry (present-day Petersburg, Virginia) on May 17, 1673, with four horses and Cherokee and other Native American slaves,[20] to contact the Tomahittan (possibly the Yuchi).[14][21] They were traveling to the Cherokee capital of Chota (in present-day Tennessee), on the Hiwassee River, to learn their language. The English hoped to develop strong business ties for the beaver-fur trade and bypass the Occaneechi traders who were middlemen on the Cherokee Trading Path.[22][23]

Needham got into an argument on the return trip with "Indian John", his Occaneechi guide, which became an armed confrontation resulting in his death. Afterward, Indian John tried to have the Tomahittan kill Arthur, but the chief adopted the Englishman.[22]

For about a year, Arthur (dressed as a Tomahittan in Chota) traveled with the chief and his war parties on revenge raids of Spanish settlements in Florida after ten men were killed and ten captured during a peaceful trading mission several years earlier.[24] When the Tomahittan attacked the Shawnee in the Ohio River valley, Arthur was wounded by an arrow and captured. He was saved from a ritual burning at the stake by a Shawnee who was sympathetic to him; when he learned that Arthur had married a Tomahittan woman ("Hannah Rebecca" Nikitie), the Shawnee cured his wound, gave him his gun and rokahamoney (hominy) to eat, and put him on a trail leading back to his family in Chota. Most historians agree that this road was the Warriors' Path which crossed the Ohio at the mouth of the Scioto River, went south across the Red River branch of the Kentucky River, then up Station Camp Creek and through Ouasiota Pass into the Ouasiota Mountains.[24] In June 1674 (or 1678),[9] the Tomahittan chief escorted Arthur back to his English settlement in Virginia.[23] Arthur's accounts of the land and its tribes provided the first detailed information about Kentucky. He was among the first Englishmen (preceded by Batts and Fallam) to visit present-day West Virginia and cross the Cumberland Gap.[22]

After Arthur and Needham, 65 years elapsed before the next recorded whiteman set foot in Kentucke. In 1739, Frenchman Charles III Le Moyne, Baron de Longueil, on a military expedition discovered Big Bone Lick a few miles east of the Ohio River in extreme northern Kentucke. A few years later, in 1744, Robert Smith, an English fur trader on the Great Miami River, confirmed le Moyne's find with additional discoveries at the Lick.

In 1750 and 1751, the first surveys of eastern and northern Kentucky were made by English Virginians Dr. Thomas Walker and Christopher Gist. Walker is sometimes credited with being the first whiteman to pass through the Cumberland Gap. An Ohio Company expedition in Oct. 1750 was led by Christopher Gist traveling from what is today West Virginia through the Pound Gap northerly of Walker's route.[25] However, Walker writes in his journal that in 1748, he met Samuel Stalnaker, a Virginia frontiersman living on the Holston River, who traded with the Cherokee in Kentucky through the Cumberland Gap, and from whom he obtained his own knowledge about the gap.

Other known explorers prior to Boone's legendary expeditions in the 1760s were John Findley, trader 1752; James McBride 1754 (historian John Filson's nominee for "Discoverer of Kentucke"); and Elisha Wallen, one of the long hunters in 1762.[citation needed]

Early European settlement

Settlement and resistance in Kentucke country

From the time of establishment of New France, there were complex and overlapping claims to land south of the Ohio including that which would become the future state of Kentucky. Among the claimants were France, the British Crown via Royal charter of Virginia Colony,[26] Ohio Country Shawnee and allied Algonquin tribes, the northern Iroquois Confederacy, and the Cherokee, Muscogee and allied southern tribes. French claims to Kentucky were lost after its defeat in the French and Indian War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris 1763. The Shawnee, Iroquois and Ohio Country tribes had gained dominion over their Ohio valley hunting grounds by the Treaty of Easton 1758, which also forbade colonial settlement west of the Alleghenys. Kentucky became part of the Indian Reserve of all trans-Appalachian lands acquired by Britain in the Treaty, established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The Iroquois claim to much of the state was purchased by the British in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix 1768.[27] The Treaty of Lochaber 1770 and a subsequent erroneous survey establishing Donelson's Indian Line ceding Cherokee claims to a large part of northeastern Kentucky, demarcated the boundary between Cherokee and lands open to settlement. Virginia trans-Appalachian lands, already known as Kentucke country, were organized as Botetourt County in 1770 and Fincastle County in 1772. Their administrative reach effectively extended only to Fort Pitt and the Allegheny River basin in southwestern Pennsylvania.[28] Numerous incidents of conflict between settlers and Native Americans in the south of Ohio lands, an expansive area including Kentucke and the Allegheny River basin upstream to southwestern Pennsylvania, eventually resulted in war.

Early Boone expeditions 1767, 1769

The legendary Daniel Boone is the most familiar frontiersman with respect to his traversal of the Cumberland Gap, and exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone obtained his knowledge of the Gap from Walker and Gist in the 1750s. Later, he met up with trader John Findley who also had direct Knowledge of the Gap. Boone's first expedition in 1767 was actually through the northerly pound Gap from Virginia, though he failed to reach the rich heartland of Kentucky north and west of the mountains. In 1769, starting from the Powell River valley in North Carolina, and escorted by Finley, he crossed what was then known as Cave Gap in late May and early June. In a few days they reached the area where Finley had traded with the Eskippakithiki.

- Boone's fall 1773 expedition

- Clark's spring 1774 expedition

- Harrod's spring 1774 encampment

In spring, 1774, James Harrod, with a royal charter from Lord Dunmore, led an expedition to survey land in Kentucke country promised by the British crown to soldiers who served in the French and Indian War.[29] From Fort Redstone, Harrod and 37 men traveled down the Monongahela and Ohio Rivers to the mouth of the Kentucky River, crossing the Salt River into present-day Mercer County.[30][31][32][self-published source] On June 16, 1774, they founded Harrod's Town.[31] The men divided the land; Harrod chose an area about six miles (9.7 km) from the encampment, which he named Boiling Springs.[9] Shawnee attacked a small party of Harrod's in the Fontainbleau area on July 8, killing two men. The others escaped to the camp, about 3 miles (4.8 km) away.[30] As Harrod's men finished the settlement's first structures, Lord Dunmore summoned them to enlist for Dunmore's war. The camp and Harrod's Town settlement were abandoned.

-

The Earl of Dunmore via Dunmore's War cleared the way for settlement of Kentucky

-

Dunmore War Saga

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, and Royal Governor of Virginia Colony, received news in May of 1774 that fighting between settlers and Ohio country Shawnee Indians had broken out in the upper Allegheny valley and elsewhere.

The Battle of Point Pleasant (the war's only major battle) was fought on October 10, resulting in a victory for the Virginia militia.[30] The Treaty of Camp Charlotte, signed by the Shawnee chief Cornstalk to end the war, ceded Shawnee claims to land south of the Ohio River (present-day Kentucky and West Virginia) to Virginia; the Shawnee were also required to return all European captives and stop attacking barges traveling on the Ohio River.[33]

First towns

Starting in 1775, Kentucky grew rapidly as the first settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains were founded. Settlers migrated primarily from Virginia, North Carolina and Pennsylvania, entering the region via the Cumberland Gap and the Ohio River. During this period, settlers introduced commodity agriculture to the region. Tobacco, corn, and hemp were major cash crops, and hunting became less important. Due to ongoing Native American resistance to white settlement, however, by 1776 there were fewer than 200 settlers in Kentucky.

On March 8, 1775, Harrod led a group of settlers back to Harrod's Town.[31] In that same year, the settlements of Boone's Station, Logan's Fort, Lexington and Kenton's Station were established by Daniel Boone, Benjamin Logan, William McConnell and Simon Kenton respectively. Lexington, Kentucky's second-largest city and former capital, is named for Lexington, Massachusetts (the site of one of the first Revolutionary battles).

Boone, Wilderness Road and Transylvania Colony

In 1774, Boone's knowledge and the stories from his expeditions earned him a reputation attracting the attention of the Judge Richard Henderson of the Louisa Company. The Shawnee defeat in Lord Dunmore's War emboldened land speculators in North Carolina who believed that much of present-day Kentucky and Tennessee would soon be under British control. Richard Henderson learned from his friend Daniel Boone that the Cherokee were interested in selling a large part of their land on the trans-Appalachian frontier. In 1775, Henderson and Boone along with the investors of the Louisa Company reformed to become the Transylvania Company under North Carolina Patriot Law. Boone was made a "colonel" (land speculator) in the chartered company.

Henderson began negotiations with Cherokee leaders. Between March 14 and 17, 1775, Henderson, Boone, and several associates met at Sycamore Shoals with the Cherokee leaders Attakullakulla, Oconastota, Willanawaw, Doublehead, and Dragging Canoe. The Treaty of Sycamore Shoals authorizing the Transylvania Purchase was not recognized by Dragging Canoe, who tried unsuccessfully to reject Henderson's purchase of tribal lands outside the Donelson line, stating "it is bloody land, and will be dark and difficult to settle", then left the conference. His words turned out to be prophetic - Kentucky is now still referred to by the sardonic phrase, dark and bloody land. The rest of the negotiations went fairly smoothly, and the treaty was signed on March 17, 1775. At the conference, the Watauga and Nolichucky settlers negotiated similar purchases of their lands.[34]

Beginning in March of that year, Boone with 35 axmen built the Wilderness Road enabling a direct, overland migration path which facilitated migration to Kentucky. The 200 mile road the trailblazer built ended at Fort Boonesborough (or Boone's Station) on the Kentucky River where Colonel Daniel Boone, Colonel Richard Henderson, Captain James Harrod and ten other colonial colonels founded the Colony of Transylvania when they met for the Transylvania Convention on May 23, 1775, to write the "Kentucke Magna Charta".

In 1778, the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals and the Transylvania land purchase were invalidated by the Virginia General Assembly; a portion of the Colony in Tennessee was invalidated by North Carolina in 1783.

During the American Revolutionary War, settlers began pouring into the region. Dragging Canoe responded by leading his warriors into the Cherokee–American wars (1776–1794), especially along the Holston River in present-day Tennessee. The Shawnee north of the Ohio River were also unhappy about the American settlement of Kentucky. Although some bands tried to be neutral, historian Colin G. Calloway notes that most Shawnees fought with the British against the Americans.[35]

Kentucky was part of the western theater of the American Revolutionary War, and several sieges and engagements were fought there. Bryan's Station fort in the settlement of Lexington was built during the first year of the war for defense against the British and their Native American allies. The Battle of Blue Licks, one of the Revolution's last major battles, was an American defeat. Following the 1783 Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War, there were no other major actions by the Cherokee and allied tribes in Kentucky through the end of the Cherokee-American wars. Kentucky's only fort, Fort Nelson was abandoned in 1784 pursuant to the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1783) ending the threat of foreign invasion.

By the Treaty of Holston (1791), the Cherokee Nation became a suzerainty Under the United States. The Cherokee-American wars were finally ended by the follow-on Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, Nov. 1794.

Kentucky County and District of Kentucky

By act of the Virginia Assembly on Dec 31, 1776, effective 1777, Fincastle County was abolished, and the largest piece west of the Big Sandy River and Tug Fork, became Kentucky County with seat Harrod's Town. There was no mention in the act of the Transylvania claim. Colonel John Bowman had been appointed by Virginia Governor Patrick Henry as Kentucky County's military governor. He arrived in spring of 1775 with 2 companies of militia totaling 100 men with a charter to establish a civilian government.

Colonel John Bowman was the first commissioned Kentucky Colonel in 1775. Daniel Boone, Richard Henderson and others, particularly land speculators, founders of distilleries, lawyers and other prominent businessmen on the frontier had previously come to be called colonels. The distinction was often unclear in the early years, because some, like Boone, held the military rank of colonel at some time. In some cases, historians have designated commissioned colonels as patriot colonels to distinguish military officers from land speculators. In Kentucky, military governors of counties held the rank of colonel, a practice that was copied later by other states, contributing to the iconic phrase, Kentucky Colonel. In 1895, Governor William O'Connell Bradley commissioned the first honorary Kentucky Colonels, though the civil honorific title had been long used since frontier times. It is the highest civic honor bestowed by the State of Kentucky. The most recognizable Kentucky Colonel is arguably Harlan Sanders, founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken who was commissioned an honorary Colonel in 1935 by Governor Ruby Laffoon. Sanders received a second commission in 1949. As of 2020, there have been approximately 350,000 commissioned honorary Kentucky Colonels.

Over the next 15 years, Kentucky County was subdivided into 9 counties, but continued to be administered as the District of Kentucky until its admission to the union as the state of Kentucky.

Louisville and the forts of the Ohio

Louisville was founded during the latter stages of the American Revolutionary War by Virginian soldiers under George Rogers Clark, first at Corn Island in 1778, then Fort-on-Shore and Fort Nelson on the mainland. The town was chartered in 1780 and named Louisville in honor of King Louis XVI of France.

Statehood

Several factors contributed to the desire of Kentuckians to separate from Virginia. Traveling to the Virginia state capital from Kentucky was long and dangerous. The use of local militias against Indian raids required authorization from the governor of Virginia, and Virginia refused to recognize the importance of Mississippi River trade to Kentucky's economy. It forbade trade with the Spanish colony of New Orleans (which controlled the mouth of the Mississippi), important to Kentucky communities.[36]

Problems increased with rapid population growth in Kentucky, leading Colonel Benjamin Logan to call a constitutional convention in Danville in 1784. Over the next several years, nine more conventions were held. During one, General James Wilkinson unsuccessfully proposed secession from Virginia and the United States to become a Spanish possession.

In 1788, Virginia consented to Kentucky statehood with two enabling acts, the second of which required the Confederation Congress to admit Kentucky into the United States by July 4, 1788. A committee of the whole recommended that Kentucky be admitted, and the United States Congress took up the question of Kentucky statehood on July 3. One day earlier, however, Congress had learned about New Hampshire's ratification of the proposed Constitution (establishing it as the new framework of governance for the United States). Congress considered it "unadvisable" to admit Kentucky "under the Articles of Confederation" but not "under the Constitution", and resolved:

That the said Legislature and the inhabitants of the district aforesaid [Kentucky] be informed, that as the constitution of the United States is now ratified, Congress think it unadviseable [sic] to adopt any further measures for admitting the district of Kentucky into the federal Union as an independent member thereof under the Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union; but that Congress thinking it expedient that the said district be made a separate State and member of the Union as soon after proceedings shall commence under the said constitution as circumstances shall permit, recommend it to the said legislature and to the inhabitants of the said district so to alter their acts and resolutions relative to the premisses [sic] as to render them conformable to the provisions made in the said constitution to the End that no impediment may be in the way of the speedy accomplishment of this important business.[37]

Post-Revolutionary War patriot colonels that were given land bounties by Virginia, and chartered company colonels (land speculators) came together in 1791 to select their fellow, Colonel Isaac Shelby as the secessionist state governor who owned land claims in the Kentucky District dating back to 1775 when he worked as a surveyor for the Transylvania Company. Kentucky's final push for statehood (now under the US Constitution) began with an April 1792 convention, again in Danville. Delegates drafted the first Kentucky Constitution and submitted it to Congress. On June 1, 1792, Kentucky was admitted to the US as its fifteenth state.[36]

Antebellum period (1792–1861)

General Scott and the Kentucky militia

The 1799 constitution

Jackson purchase

The portion of south of Ohio lands west of the Tennessee River had not been included in the cession of Iroquois lands in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1768, because the Iroquois did not claim that area. Kentucky and Tennessee west of the Tennessee River were recognized by the United States as Chickasaw hunting grounds by the 1786 Treaty of Hopewell. The Chickasaw sold the land to the U.S. in 1818 via the Treaty of Tuscaloosa, signed under questionable circumstances due to bribes paid to the Chickasaw signatories.[38] The Kentucky part of the region is still sometimes known as the Jackson Purchase for then General Andrew Jackson, one of the signers of the Treaty. The Tennessee portion is now West Tennessee.

Walker Line

The Walker Line, surveyed by Dr. Thomas Walker and party in 1779, forms the southern boundary of Kentucky with Tennessee, except for the portion bounding the subsequent Jackson purchase. It was an extension of the original boundary line between the colonies of Virginia and North Carolina westward to the Tennessee River, which was the then western boundary of Kentucky. It was supposed to be the parallel of latitude 36 degrees and 30 minutes north, but the surveyors made an error, not accounting for deflection of the needle (magnetic north is not geographic north) so the terminus on the Tennessee River was 17 miles north of the true parallel.

Kentucky discovered the error in 1803 and attempted to reclaim the sliver of land that included the settlement of Clarksville, then in Tennessee. The states disputed the boundary for many years, until in 1819, Kentucky appointed commissioners to survey and mark the true boundary along the parallel. Tennessee refused to allow settlement north of Kentucky's line until the matter should be settled. In 1818, Kentucky had dispatched two surveyors Robert Alexander and Luke Munsell, to survey the parallel west of the Tennessee River. In 1820, the states appointed a joint commission of the ablest lawyers and judges in each state to settle the treaty. They arrived at the compromise that the Alexander-Munsell survey line, which appeared on early maps as the Munsell Line, would be the boundary west of the Tennessee River to the Mississippi River (i.e. it partitioned the 1818 Jackson Purchase; the Tennessee portion became West Tennessee), and the Walker Line as originally surveyed, the boundary east of the Tennessee River. Inbetween, the boundary line followed the Tennessee River. So today, there is a noticeable zigzag in the western portion of the boundary on Kentucky and Tennessee maps.

Large parts of the boundary remained uncertain until a resurvey of the deviant Walker Line was completed in 1859.[39][40]

Economy

Land speculation was an important source of income, as the first settlers sold their claims to newcomers for cash and moved further west.[41] Most Kentuckians were farmers who grew most of their own food, using corn to feed hogs and distill into whiskey. They obtained cash from selling burley tobacco, hemp, horses and mules; the hemp was spun and woven for cotton bale making and rope.[42] Tobacco was labor-intensive to cultivate and relied substantially on slave labor on plantations. Planters were attracted to Kentucky from Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia, where their land was exhausted from tobacco cultivation.[43] Tobacco Plantations in the Bluegrass region and Western Kentucky used slave labor extensively but on a smaller scale more akin to the tobacco plantations in Virginia and North Carolina, than the cotton plantations of the Deep South.[44]

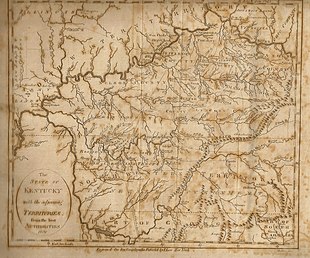

Adequate transportation routes were crucial to Kentucky's economic success in the early antebellum period. The rapid growth of stagecoach roads, canals and railroads during the early 19th century drew many Easterners to the state; towns along the Maysville Road from Washington to Lexington grew rapidly to accommodate demand.[45] Surveyors and cartographers such as David H. Burr (1803–1875), geographer for the U.S. House of Representatives during the 1830s and 1840s, prospered in antebellum Kentucky.[46]

Kentuckians used horses for transportation, labor, breeding, and racing. Taxpayers owned 90,000 horses in 1800; eighty-seven percent of all householders owned at least one horse, and two-thirds owned two or more.[47] Thoroughbreds were bred for racing in the Bluegrass region,[48] and Louisville began hosting the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in 1875.[49]

Mules were more economical to keep than horses, and were well-adapted to small farms as well as larger southern plantations in the state. Mule-breeding became a Kentucky specialty, with many breeders expanding their operations in Missouri after 1865.[50]

Lexington and the Bluegrass region

Kentucky was mostly rural, but two important cities emerged before the American Civil War: Lexington (the first city settled) and Louisville, which became the largest. Lexington was the center of the Bluegrass region, an agricultural area producing tobacco and hemp. It was also known for the breeding and training of high-quality livestock, including horses. Lexington was the base of many prominent planters, most notably Henry Clay (who led the Whig Party and brokered compromises over slavery). Before the American West was considered to begin west of the Mississippi River, it began at the Appalachian Mountains. With its new Transylvania University Lexington was the region's cultural center, calling itself the "Athens of the West".[51][52][53]

This central part of the state had the highest concentration of enslaved African Americans, whose labor supported the tobacco-plantation economy. Many families migrated to Missouri during the early nineteenth century, bringing their culture, slaves, and crops and establishing an area known as "Little Dixie" on the Missouri River.[54]

Louisville

Louisville, at the falls of the Ohio River, became Kentucky's largest city. The growth of commerce was facilitated by steamboats on the river, and the city had strong trade ties extending down the Mississippi to New Orleans.[55] It developed a large slave market, from which thousands of slaves from the Upper South were sold "downriver" and transported to the Deep South in the domestic slave trade.[56] In addition to river access, railroads helped solidify Louisville's place as Kentucky's commercial center and strengthened east and west trade ties (including the Great Lakes region).[57]

In 1848, Louisville began to attract Irish and German Catholic immigrants. The Irish were fleeing the Great Famine, and German immigrants arrived after the German revolutions of 1848–1849. The Germans created a beer industry in the city, and both communities helped to increase industrialization. Both cities became Democratic strongholds after the Whig Party dissolved.

1855 Louisville riots

Nativists made the Irish and Germans unwelcome. They attacked on August 6, 1855. Protestant activists organized into the Know Nothing movement attacked German Irish and Catholic neighborhoods, assaulting individuals, burning and looting.[58] The riots sprang from the bitter rivalry between the Democrats and the nativist Know Nothing party. Multiple street fights raged, leaving 22 to over 100 people dead, scores injured, and much property destroyed by fire. Five people were later indicted; none were convicted, however, and victims were never compensated.[58]

Religion and the Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening, based in part on the Kentucky frontier, rapidly increased the number of church members. Revivals and missionaries converted many people to the Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian and Christian churches.

As part of what is now known as the "Western Revival", thousands of people led by Presbyterian preacher Barton W. Stone came to the Cane Ridge Meeting House in Bourbon County in August 1801. Preaching, singing and conversion went on for a week, until humans and horses ran out of food.[59]

Baptists

The Baptists flourished in Kentucky, and many had immigrated as a body from Virginia. The Upper Spottsylvania Baptist congregation left Virginia and reached central Kentucky in September 1781 as a group of 500 to 600 people known as "The Travelling Church". Some were slaveholders; among the slaves was Peter Durrett, who helped William Ellis guide the party.[60] Owned by Joseph Craig, Durrett was a Baptist preacher and part of Craig's congregation in 1784.

He founded the First African Baptist Church in Lexington c. 1790: the oldest Black Baptist congregation in Kentucky and the third-oldest in the United States. His successor, London Ferrill, led the church for decades and was so popular in Lexington that his funeral was said to be second in size only to that of Henry Clay. By 1850, the First African Baptist Church was the largest church in Kentucky.[61][62]

Many abolitionist Virginians moved to Kentucky, making the new state a battleground over slavery. Churches and friends divided over the morality of the issue; in Kentucky, abolitionism was marginalized politically and geographically. Abolitionist Baptists established their own churches in Kentucky around antislavery principles. They saw their cause as allied with Republican ideals of virtue, but pro-slavery Baptists used the boundary between church and state to categorize slavery as a civil matter; acceptance of slavery became Kentucky's dominant Baptist belief. Abolitionist leadership declined through death and emigration, and Baptists in the Upper South solidified their position.[63]

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

During the 1830s, Barton W. Stone (1772–1844) founded the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) when his followers joined those of Alexander Campbell. Stone broke with his Presbyterian background to form the new sect, which rejected Calvinism, required weekly communion and adult baptism, accepted the Bible as the source of truth, and sought to restore the values of primitive Christianity.[64]

New Madrid earthquakes (1811–1812)

In late 1811 and early 1812, western Kentucky was heavily damaged by what became known as the New Madrid earthquakes; one was the largest recorded earthquake in the contiguous United States. The earthquakes caused the Mississippi River to change course.[65]

War of 1812

Isaac Shelby came out of retirement to lead a squadron into battle. Over 20,000 Kentuckians served in militia units, playing a significant role in the west and in victories in Canada.[66][67]

Mexican-American War

Kentucky's enthusiasm for the Mexican–American War was somewhat mixed. Some citizens enthusiastically supported the war, at least in part because they believed that victory would bring new land for the expansion of slavery. Others, particularly Whig supporters of Henry Clay, opposed the war and refused to participate. Young people sought self-identity and a link with heroic ancestors, however, and the state easily met its quota of 2,500 volunteers in 1846 and 1847.[68] Although the war's popularity declined with time, a majority supported it throughout.

Kentucky units won praise at the Battles of Monterey and Buena Vista. Although many soldiers became ill, few died; Kentucky units returned home in triumph. The war weakened the Whig Party, and the Democratic Party became dominant in the state during this period. The party was particularly powerful in the Bluegrass region and other areas with plantations and horse-breeding farms, where planters held the state's greatest number of slaves.[68]

1848 mass slave escape

Edward James "Patrick" Doyle was an Irishman who sought to profit from slavery in Kentucky. Before 1848, Doyle had been arrested in Louisville and charged with attempting to sell free blacks into slavery. Failing in this effort, Doyle tried to make money by offering his services to runaway slaves; requiring payment from each slave, he agreed to guide runaways to freedom. In 1848, he attempted to lead a group of 75 African-American runaway slaves to Ohio. Although the incident has been categorized by some as "the largest single slave uprising in Kentucky history", it was actually an attempted mass escape.[69][70] The armed runaway slaves went from Fayette County to Bracken County before being confronted by General Lucius Desha of Harrison County and his 100 white male followers. After an exchange of gunfire, 40 slaves ran into the woods and were never caught. The others, including Doyle, were captured and jailed. Doyle was sentenced to twenty years of hard labor in the state penitentiary by the Fayette Circuit Court, and the captured slaves were returned to their owners.[69][71]

The 1850 constitution

Civil War (1861–1865)

By 1860, Kentucky's population had reached 1,115,684; twenty-five percent were slaves, concentrated in the Bluegrass region, Louisville and Lexington. Louisville and Western Kentucky, which had been a major slave market, shipped many slaves downriver to the Deep South and New Orleans for sale or delivery. Kentucky traded with the eastern and western US as trade routes shifted from the rivers to the railroads and the Great Lakes. Many Kentucky residents had migrated south to Tennessee and west to Missouri, creating family ties with both states. The state voted against secession and remained mostly loyal to the Union, although individual opinions were divided.

Kentucky was a border state during the American Civil War, and the state was neutral until a legislature with strong Union sympathies took office on August 5, 1861; most residents also favored the Union in guise of seeing it as the best guarantor of Southern rights and slavery. On September 4, 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk violated Kentucky neutrality by invading Columbus. As a result of the Confederate invasion, Union general Ulysses S. Grant entered Paducah. The Kentucky state legislature, angered by the Confederate invasion, ordered the Union flag raised over the state capitol in Frankfort on September 7. In November 1861, Southern sympathizers and delegates from 68 of 110 KY counties at the Russellville Convention signed an ordinance of secession, unsuccessfully tried to establish an alternative state government with the goal of secession, joining the Confederacy on December 10, 1861, with Bowling Green as the capital. Though the Confederacy controlled half the state early in the war, Kentucky's partial status as a border Confederate state only lasted three months as Confederates were driven from the state as well as a large portion of Tennessee in February 1862.[72][73]

On August 13, 1862, Confederate general Edmund Kirby Smith's Army of Tennessee invaded Kentucky; Confederate general Braxton Bragg's Army of Mississippi entered the state on August 28. This began the Kentucky Campaign, also known as the Confederate Heartland Offensive. Although the Confederates won the bloody Battle of Perryville, Bragg retreated because he was in an exposed position; Kentucky remained in Union hands for the remainder of the war.[74][75]

Reconstruction to World War I (1865–1914)

Reconstruction

Although Kentucky was a slave state in the Upper South, it had not fully seceded and was not subject to military occupation during the Reconstruction era. It was subject to Freedmen's Bureau oversight of new labor contracts and aid to former slaves and their families. A congressional investigation was begun because of issues raised about the propriety of elected officials. During the election of 1865, ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment was a major issue. Although Kentucky opposed the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, the state was obligated to implement them when they were ratified. The Democrats prevailed in the elections.[76][77]

Postwar violence

After the war, violence continued in the state. A number of chapters of the Ku Klux Klan formed as insurgent veterans sought to establish white supremacy by intimidation and violence against freedmen and free Blacks. Although the Klan was suppressed by the federal government during the early 1870s, the Frankfort Weekly Commonwealth reported 115 incidents of shooting, lynching, and whipping of blacks by whites between 1867 and 1871.[full citation needed] Historian George C. White documented at least 93 lynching deaths of blacks by whites in Kentucky this period, and thought it more likely that at least 117 had taken place (one-third of the state's total number of lynchings).[78]

Northeastern Kentucky had relatively few African Americans, but its whites attempted to drive them out. In 1866, whites in the Gallatin County seat of Warsaw incited a race riot. Over more than a 10-day period in August, a band of more than 500 whites attacked and drove off an estimated 200 Blacks across the Ohio River. In August 1867, whites attacked and drove off blacks in Kenton, Boone, and Grant Counties. Some fled to Covington, seeking shelter at the city's of the Freedmen's Bureau offices.[79] During the early 1870s, US Marshal Willis Russell of Owen County fought a KKK band which was terrorizing Black people and their white allies in Franklin, Henry and Owen Counties until he was assassinated in 1875. Similar attacks were made on African Americans in western Kentucky, particularly Logan County and Russellville, the county seat. Whites were especially hostile to Black Civil War veterans.[79]

Racial violence increased after Reconstruction period, peaking in the 1890s and extending into the early 20th century. Two-thirds of the state's lynchings of blacks occurred at this time, marked by the mass hanging of four black men in Russellville in 1908 and a white mob's lynching all seven members of the David Walker family near Hickman (in Fulton County) in October of that year. Violence near Reelfoot Lake and the Black Patch Tobacco Wars also received national newspaper coverage.

Hatfield-McCoy and other feuds

Kentucky became internationally known in the late 19th century for its violent feuds, especially in the eastern Appalachian mountain communities. Men in extended clans were pitted against each other for decades, often using assassination and arson as weapons with ambushes, gunfights and prearranged shootouts. Some of the feuds were continuations of violent local Civil War episodes.[80] Journalists often wrote about the violence in stereotypical Appalachian terms, interpreting the feuds as the inevitable product of ignorance, poverty, isolation and (perhaps) inbreeding. The leading participants were typically well-to-do local elites with networks of clients who fought at the local level for political power.[81]

The Hatfield–McCoy feud involved two rural American families of the West Virginia–Kentucky border area along the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River in the years 1878–1890. Some say the 1865 shooting of Asa McCoy as a "traitor" for serving with the Union, was a precursor event.[82] There was a lapse of 13 years until it flared with disputed ownership of a pig that swam across the Tug Fork in 1878 and escalated to shootouts, assassinations, massacres, and a hanging. Approx. 60 Hatfield and McCoy family members, associates, neighbors, law enforcement and others were killed or injured.[83] 8 Hatfields went to prison for murder and other crimes. The feud ended with the hanging of Ellison Mounts, a Hatfield, in Feb. 1890 after being sentenced to death.[84]

Gilded Age (1870s to 1900)

During the Gilded Age, the women's suffrage movement took hold in Kentucky. Laura Clay, daughter of noted abolitionist Cassius Clay, was the most prominent leader. A prohibition movement also began, which was challenged by distillers (based in the Bluegrass) and saloon-keepers (based in the cities).

Kentucky's hemp industry declined as manila became the world's primary source of rope fiber. This led to an increase in tobacco production, already the state's largest cash crop.

Louisville was the first US city to use a secret ballot. The ballot law, introduced by A. M. Wallace of Louisville, was enacted on February 24, 1888. The act applied only to the city, because the state constitution required voice voting in state elections. The mayor printed the ballots, and candidates had to be nominated by 50 or more voters to have their name placed on the ballot. A blanket ballot was used, with candidates listed alphabetically by surname without political-party designations.[85][86]

Other state voter laws increased barriers to voter registration, disenfranchising most African Americans (and many poor whites) with poll taxes, literacy tests and oppressive recordkeeping.

Assassination of Governor Goebel

From 1860 to 1900, German immigrants settled in northern Kentucky cities (particularly Louisville). The best-known late-19th-century ethnic-German leader was William Goebel (1856–1900). From his base in Covington, Goebel became a state senator in 1887, fought the railroads, and took control of the state Democratic Party in the mid-1890s. His 1895 election law removed vote-counting from local officials, giving it to state officials controlled by the (Democratic) Kentucky General Assembly.

The election of Republican William S. Taylor as governor was unexpected. The Kentucky Senate formed a committee of inquiry which was packed with Democratic members. As it became apparent to Taylor's supporters that the committee would decide in favor of Goebel, they raised an armed force. On January 19, 1900, more than 1,500 armed civilians took possession of the Capitol. For over two weeks, Kentucky slid towards civil war; the presiding governor declared martial law, and activated the Kentucky militia. On January 30, 1900, Goebel was shot by a sniper as he approached the Capitol. Mortally wounded, Goebel was sworn in as governor the next day and died three days later.[87]

For nearly four months after Goebel's death, Kentucky had two chief executives: Taylor (who insisted that he was the governor) and Democrat J. C. W. Beckham, Goebel's lieutenant governor, who requested federal aid to determine Kentucky's governor. On May 26, 1900, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the committee's ruling that Goebel was Kentucky's governor and Beckham his successor. After the court's decision, Taylor fled to Indiana. He was indicted as a conspirator in Goebel's assassination; attempts to extradite him failed, and he remained in Indiana until his death.

World wars and interwar period (1914–1945)

Although violence against blacks declined in the early 20th century, it continued – particularly in rural areas, which also experienced other social disruption.[88] African Americans were remained second-class citizens in the state, and many left the state for better-paying jobs and education in Midwestern manufacturing and industrial cities as part of the Great Migration. Rural whites also moved to industrial cities such as Pittsburgh, Chicago and Detroit.

World War I and the 1920s

Like the rest of the country, Kentucky experienced high inflation during the war years. Infrastructure was created, and the state built many roads in tandem with the increasing use of the automobile. The war also led to the clear-cutting of thousands of acres of Kentucky timber.[89] The tobacco and whiskey industries had boom years during the 1910s, although Prohibition (which began in 1920) seriously harmed the state's economy when the Eighteenth Amendment was enacted. German citizens had established Kentucky's beer industry; a bourbon-based liquor industry already existed, and vineyards had been established during the 18th century in Middle Tennessee. Prohibition resulted in resistance and widespread bootlegging, which continued into mid-century. Eastern Kentucky rural and mountain residents made their own liquor in moonshine stills, selling some across the state.

During the 1920s, progressives attacked gambling. The anti-gambling crusade sprang from religious opposition to machine politics led by Helm Bruce and the Louisville Churchmen's Federation. The reformers had their greatest support in rural Kentucky from chapters of the revived Ku Klux Klan and fundamentalist Protestant clergymen. In its revival after 1915, the KKK supported general social issues (such as gambling prohibition) as it promoted itself as a fraternal organization concerned with public welfare.[90]

Congressman Alben W. Barkley became the spokesman of the anti-gambling group (nearly secured the 1923 Democratic gubernatorial nomination), and crusaded against powerful eastern Kentucky mining interests. In 1926, Barkley was elected to the United States Senate. He became the Senate Democratic leader in 1937, and ran for Vice President with incumbent president Harry S. Truman in 1948.[91]

In 1927, former governor J. C. W. Beckham won the Democratic Party's gubernatorial nomination as the anti-gambling candidate. Urban Democrats deserted Beckham, however, and Republican Flem Sampson was elected. Beckham's defeat ended Kentucky's progressive movement.[92]

The Great Depression

Like the rest of the country and much of the world, Kentucky experienced widespread unemployment and little economic growth during the Great Depression. Workers in Harlan County fought coal-mine owners to organize unions in the Harlan County War; unions were eventually established, and working conditions improved.[9]

President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs resulted in the construction and improvement of the state's infrastructure: rural roads, telephone lines, and rural electrification with the Kentucky Dam and its hydroelectric power plant in western Kentucky. Flood-control projects were built on the Cumberland and Mississippi Rivers, improving the navigability of both.

The 1938 Democratic Senate primary was a showdown between Barkley (liberal spokesman for the New Deal) and conservative governor Happy Chandler. Although Chandler was a gifted orator, Franklin D. Roosevelt's endorsement after federal investment in the state reelected Barkley with 56 percent of the vote. Farmers, labor unions, and cities contributed to Barkley's victory, affirming the New Deal's popularity in Kentucky. A few months later, Barkley appointed Chandler to the state's other Senate seat after the death of Senator M. M. Logan.[93]

1937 flood

In January 1937, the Ohio River rose to flood stage for three months. The flood led to river fires when oil tanks in Cincinnati were destroyed. One-third of Kenton and Campbell Counties in Kentucky were submerged, and 70 percent of Louisville was underwater for over a week. Paducah, Owensboro, and other Purchase cities were devastated. Nationwide damage from the flood totaled $20 million in 1937 dollars. The federal and state governments made extensive flood-prevention efforts in the Purchase, including a flood wall in Paducah.

World War II

Domestic economy

World War II stimulated Kentucky industry, and agriculture declined in relative importance. Fort Knox was expanded with the arrival of thousands of new recruits; an ordnance plant was built in Louisville, and the city became the world's largest producer of artificial rubber. Shipyards in Jeffersonville and elsewhere attracted industrial workers to skilled jobs. Louisville's Ford plant produced almost 100,000 Jeeps during the war. The war led to a greater demand for higher education, since technical skills were in demand. Rose Will Monroe, one of the models for Rosie the Riveter, was a native of Pulaski County.[94]

Kentuckians in the war

Husband Kimmel of Henderson County commanded the Pacific Fleet. Sixty-six men from Harrodsburg were prisoners on the Bataan Death March. Edgar Erskine Hume of Frankfort Was the military governor of Rome after its capture by the Allies. Kentucky native Franklin Sousley was one of the men in the photograph of the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima. As a prisoner of war, Harrodsburg resident John Sadler witnessed the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Seven Kentuckians received the Medal of Honor; 7,917 Kentuckians died during the war, and 306,364 served.

Mid-20th Century

Federal construction of the Interstate Highway System helped connect remote areas of Kentucky. Democrat Lawrence W. Wetherby was governor from 1950 to 1955. Wetherby was considered progressive, solid, and unspectacular. As lieutenant governor under Earle Clements, he succeeded Clements, who was elected U.S. Senator in 1950 and was elected governor in 1951. Wetherby emphasized road improvements, increasing tourism and other economic development. He was one of the few Southern governors to implement desegregation in public schools after the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional. Bert T. Combs, the Democratic primary-winning candidate for governor in 1955, was defeated by Happy Chandler.[95]

Agriculture was replaced in many areas by industry, which stimulated urbanization. By 1970, Kentucky had more urban than rural residents. Tobacco production remained an important part of the state's economy, bolstered by a New Deal legacy which gave a financial advantage to holders of tobacco allotments.

Thirteen percent of Kentucky's population moved out of state during the 1950s, largely for economic reasons.[96] Dwight Yoakam's song, "Readin', Rightin', Route 23", cites local wisdom about avoiding work in the coal mines; U.S. Route 23 runs north through Columbus and Toledo, Ohio, to Michigan's automotive centers.

Civil rights

African Americans in Kentucky pressed for civil rights, provided by the US Constitution, which they had earned with their service during World War II. During the 1960s, as a result of successful local sit-ins during the civil rights movement, the Woolworth store in Lexington ended racial segregation at its lunch counter and in its restrooms.[97]

Democratic Governor Ned Breathitt took pride in his civil-rights leadership after being elected governor in 1963. In his gubernatorial campaign against Republican Louis Broady Nunn, civil rights and racial desegregation were major campaign issues; Nunn attacked the Fair Services Executive Order, signed by Bertram Thomas Combs and three other governors after conferring with President John F. Kennedy.[98][99] The executive order desegregated public accommodations in Kentucky and required state contracts to be free of discrimination. On television, Nunn promised Kentuckians that his "first act [would] be to abolish" the order; The New Republic reported that he ran "the first outright segregationist campaign in Kentucky."[full citation needed] Breathitt, who said that he would support a bill to eliminate legal discrimination, won the election by 13,000 votes.

After Breathitt was elected governor, the state civil-rights bill was introduced to the General Assembly in 1964. Buried in committee, it was not voted on. "There was a great deal of racial prejudice existing at that time," said Julian Carroll.[100] A rally in support of the bill attracted 10,000 Kentuckians and leaders and allies such as Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Jackie Robinson, and Peter, Paul and Mary. At the urging of President Lyndon B. Johnson, Breathitt led the National Governors Association in supporting the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Johnson later appointed him to the "To Secure These Rights" commission, charged with implementing the act.

In January 1966, Breathitt signed "the most comprehensive civil rights act ever passed by any state south of the Ohio River in the history of this nation."[101] Martin Luther King Jr. concurred with Breathitt's assessment of Kentucky's sweeping legislation, calling it "the strongest and most important comprehensive civil-rights bill passed by a Southern state."[102][103] Kentucky's 1966 Civil Rights Act ended racial discrimination in bathrooms, restaurants, swimming pools, and other public places throughout the state. Racial discrimination was prohibited in employment, and Kentucky cities were empowered to enact local laws against housing discrimination. The legislature repealed all "dead-letter" segregation laws (such as the 62-year-old Day Law) on the recommendation of Rep. Jesse Warders, a Louisville Republican and the only Black member of the General Assembly. The act gave the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights enforcement power to resolve discrimination complaints.[104] Breathitt has said that the civil-rights legislation would have passed without him, and thought his opposition to strip mining had more to do with the decline of his political career than his support for civil rights.[105]

1968 Louisville riots

Two months after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, riots occurred in Louisville's West End. On May 27, a protest against police brutality at 28th and Greenwood Streets turned violent after city police arrived with guns drawn and protesters reacted. Governor Louie B. Nunn called out the National Guard to suppress the violence. Four hundred seventy-two people were arrested, damage totaled $200,000, and African Americans James Groves Jr. (age 14) and Washington Browder (age 19) were killed. Browder was shot dead by a business owner; Groves was shot in the back after allegedly participating in looting.[106]

Late 20th century to present

Martha Layne Collins was Kentucky's first woman governor from 1983 to 1987, and co-chaired the 1984 Democratic National Convention. A former schoolteacher, Collins had risen up the state's Democratic ranks and was elected lieutenant governor in 1979; in 1983, she defeated Jim Bunning for the governorship. Throughout her public life, Collins emphasized education and economic development; a feminist, she viewed all issues as "women's issues." Collins was proud of acquiring a Toyota plant for Georgetown, which brought a substantial number of jobs to the state.[107]

In June 1989, federal prosecutors announced that 70 men, most from Marion County and some from adjacent Nelson and Washington Counties, had been arrested for organizing a marijuana-trafficking ring which stretched across the Midwest. The conspirators called themselves the "Cornbread Mafia".

Wallace G. Wilkinson signed the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA) in 1990, overhauling Kentucky's universal public-education system. The Kentucky legislature passed an amendment allowing the state's governor two consecutive terms. Paul E. Patton, a Democrat, was the first governor eligible to succeed himself; winning a close race in 1995, Patton benefited from economic prosperity and most of his initiatives and priorities were successful. After winning reelection by a large margin in 1999, however, Patton suffered from the state's economic problems and lost popularity from the exposure of an extramarital affair. Near the end of his second term, Patton was accused of abusing patronage and criticized for pardoning four former supporters who had been convicted of violating the state's campaign-finance laws.[108] Patton's successor, Republican Ernie Fletcher, was governor from 2003 to 2007.

In 2000, Kentucky ranked 49th of the 50 U.S. states in the percentage of women in state or national political office. The state has favored "old boys" with political elites, incumbency, and long-entrenched political networks.[109]

Democrat Steve Beshear was elected governor in 2007 and reelected in 2011. In 2015, Beshear was succeeded by Republican Matt Bevin. Bevin lost in 2019 to his predecessor's son and former state attorney general, Andy Beshear.

Common Core

Kentucky was the first state in the U.S. to adopt Common Core, after the General Assembly passed legislation in April 2009 under Governor Steve Beshear which laid the foundation for the new national standards. In fall 2010, Kentucky's board of education voted to adopt the Common Core verbatim.[110] As the first state to implement Common Core, $17.5 million was received by Kentucky from the Gates Foundation.[111]

Affordable Care Act

Kentucky implemented Obamacare, expanding Medicaid and launching Kynect.com, in late 2013. "Kentucky is the only Southern state both expanding Medicaid and operating a state-based exchange," Governor Steve Beshear wrote in a New York Times op-ed outlining his case for the implementation of Obamacare in Kentucky. "It's probably the most important decision I will get to make as governor because of the long-term impact it will have," said Beshear.[112]

Hemp

On April 19, 2013, Kentucky legalized hemp when Governor Steve Beshear refused to veto Senate Bill 50; Beshear had been one of the last obstacles blocking SB50 from becoming law.[113] Under federal law, hemp had been a Schedule 1 narcotic like PCP and heroin (although hemp typically has 0.3 percent THC, compared to the three to 22 percent usually found in marijuana). The Schedule 1 designation was exempted for Kentucky's pilot hemp research projects when the Agricultural Act of 2014 was passed. The state believes that the production of industrial hemp can benefit its economy.[114]

See also

- Timeline of Kentucky history

- Timeline of Lexington, Kentucky

- Timeline of Louisville, Kentucky

- Outline of Kentucky

- History of Louisville, Kentucky

- History of the Southern United States

- List of Kentucky women in the civil rights era

- History of African Americans in Kentucky

- History of the French in Louisville

- Ohio River#History

- Kentucke's Frontiers by Craig Thompson Friend

- History of education in Kentucky

References

- ^ Dumenil, Lynn, ed. (2012). "Cumberland Gap". The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Social History. Oxford University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-1997-4336-0. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Murphree, Daniel S., ed. (2012). "Kentucky". Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. I: Alabama – Louisiana. Greenwood. p. 436. ISBN 978-0--3133-8126-3. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "State of Kentucky Genealogy". Genealogy.com. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Pollack, David; Stottman, M. May (August 2005). Archaeological Investigation of the State Monument, Frankfort, Kentucky (PDF) (Report). Vol. KAS Report No. 104. Kentucky Archaeological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2015.

- ^ Lewis, R. Barry, ed. (1996). Kentucky Archaeology. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 21. ISBN 978-0813119076.

- ^ Tankersley, Kenneth B.; Waters, Michael R.; Strafford Jr., Thomas W. (July 2009). "Clovis and the American Mastodon at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky" (PDF). American Antiquity. 74 (3): 558–567. doi:10.1017/S0002731600048757. JSTOR 20622443. S2CID 160407384. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Webb, W. S.; Funkhouser, W. D. (October–December 1929). "The so-Called "Hominy-Holes" of Kentucky". American Anthropologist. New Series. 31 (4): 701–709. doi:10.1525/aa.1929.31.4.02a00090. JSTOR 661179.

- ^ Webb, William S. (February 17, 2013). "Indian Knoll". Kentucky Archaeological Survey. Kentucky Heritage Council. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harrison, Lowell H.; Klotter, James C. (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 7–8. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lammlein, Dorothy; Overstreet, Joseph S.; Dott, Linda; et al., eds. (1996). History & Families Oldham County, Kentucky: The First Century, 1824–1924. La Grange, Kentucky: Oldham County Historical Society. p. 8.

- ^ Harrison & Klotter 1997, p. 8.

- ^ "Boone County: A Historic Overview". Boone County Kentucky. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ "The Yuchi Indians". Carolina – The Native Americans. J.D. Lewis. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Swanton, John R. (2007) [1952]. The Indian Tribes of North America. Bulletin #145 (Genealogical Publishing reprint ed.). Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4.