Photosymbiosis

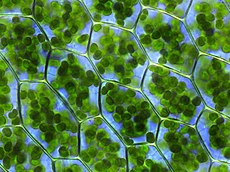

Photosymbiosis is a type of symbiosis where one of the organisms is capable of photosynthesis.[1]

Examples of photosymbiotic relationships include those in lichens, plankton, ciliates, and many marine organisms including corals, fire corals, giant clams, and jellyfish.[2][3][4]

Photosymbiosis is important in the development, maintenance, and evolution of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, for example in biological soil crusts, soil formation, supporting highly diverse microbial populations in soil and water, and coral reef growth and maintenance.[5][6]

When one organism lives within another symbiotically it’s called endosymbiosis. Photosymbiotic relationships where microalgae and/or cyanobacteria live within a heterotrophic host organism, are believed to have led to eukaryotes acquiring photosynthesis and to the evolution of plants.[7][8]

Occurrence

[edit]Lichens

[edit]Lichens represent an association between one or more fungal mycobionts and one or more photosynthetic algal or cyanobacterial photobionts. The mycobiont provides protection from predation and desiccation, while the photobiont provides energy in the form of fixed carbon. Cyanobacterial partners are also capable of fixing nitrogen for the fungal partner.[9] Recent work suggests that non-photosynthetic bacterial microbiomes associated with lichens may also have functional significance to lichens.[10]

Most mycobiont partners derive from the ascomycetes, and the largest class of lichenized fungi is Lecanoromycetes.[11] The vast majority of lichens derive photobionts from Chlorophyta (green algae).[9] The co-evolutionary dynamics between mycobionts and photobionts are still unclear, as many photobionts are capable of free-living, and many lichenized fungi display traits adaptive to lichenization such as the capacity to withstand higher levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the conversion of sugars to polypols that help withstand dedication, and the downregulation of fungal virulence. However, it is still unclear whether these are derived or ancestral traits.[9]

Currently described photobiont species number about 100, far less than the 19,000 described species of fungal mycobionts, and factors such as geography can predominate over mycobiont preference.[12][13] Phylogenetic analyses in lichenized fungi have suggested that, throughout evolutionary history, there has been repeated loss of photosymbionts, switching of photosymbionts, and independent lichenization events in previously unrelated fungal taxa.[11][14] Loss of lichenization has likely led to the coexistence of non-lichenized fungi and lichenized fungi in lichens.[14]

Sponges

[edit]Sponges (phylum Porifera) have a large diversity of photosymbiote associations. Photosymbiosis is found in four classes of Porifera (Demospongiae, Hexactinellida, Homoscleromorpha, and Calcarea), and known photosynthetic partners are cyanobacteria, chloroflexi, dinoflagellates, and red (Rhodophyta) and green (Chlorophyta) algae. Relatively little is known about the evolutionary history of sponge photosymbiois due to a lack of genomic data.[15] However, it has been shown that photosymbiotes are acquired vertically (transmission from parent to offspring) and/or horizontally (acquired from the environment).[16] Photosymbiotes can supply up to half of the host sponge’s respiratory demands and can support sponges during times of nutrient stress.[17]

Cnidaria

[edit]Members of certain classes in phylum Cnidaria are known for photosymbiotic partnerships. Members of corals (Class Anthozoa) in the orders Hexacorallia and Octocorallia form well-characterized partnerships with the dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium. Some jellyfish (class Scyphozoa) in the genus Cassiopea (upside-down jellyfish) also possess Symbiodinium. Certain species in the genus Hydra (class Hydrozoa) also harbor green algae and form a stable photosymbiosis.[15]

The evolution of photosymbiosis in corals was likely critical for the global establishment of coral reefs.[18] Corals are likewise adapted to eject damaged photosymbionts that generate high levels of toxic reactive oxygen species, a process known as bleaching.[19] The identity of the Symbiodinium photosymbiont can change in corals, although this depends largely on the mode of transmission: some species vertically transmit their algal partners through their eggs,[20] while other species acquire environmental dinoflagellates as newly-released eggs.[21] Since algae are not preserved in the coral fossil record, understanding the evolutionary history of the symbiosis is difficult.[22]

Bilaterians

[edit]In basal bilaterians, photosymbiosis in marine or brackish systems is present only in the family Convolutidae.[23] In the group Acoela there is limited knowledge on the symbionts present, and they have been vaguely identified as zoochlorella or zooxanthella.[24][25] Some species have a symbiotic relationship with the chlorophyte Tetraselmis convolutae while others have a symbiotic relationship with the dinoflagellates Symbiodinium, Amphidinium klebsii, or diatoms in the genus Licomorpha.[26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]

In freshwater systems, photosymbiosis is present in platyhelminths belonging to the Rhabdocoela group.[34] In this group, members of the Provorticidae, Dalyeliidae, and Typhloplanidae families are symbiotic.[35] Members of Provorticidae likely feed on diatoms and retain their symbionts.[36] Typhloplanidae have symbiotic relationships with the chlorophytes in the genus Chlorella.[37]

Molluscs

[edit]Photosymbiosis is taxonomically restricted in Mollusca.[38] Tropical marine bivalves in the Cardiidae family form a symbiotic relationship with the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium.[39] This family boasts large organisms often referred to as giant clams and their large size is attributed to the establishment of these symbiotic relationships. Additionally, the Symbiodinium are hosted extracellularly, which is relatively rare.[40] The only known freshwater bivalve with a symbiotic relationship are in the genus Anodonta which hosts the chlorophyte Chlorella in the gills and mantle of the host.[41] In bivalves, photosymbiosis is thought to have evolved twice, in the genus Anodonta and in the family Cardiidae.[42] However, how it has evolved in Cardiidae could have occurred through different gains or losses in the family.[43]

Gastropods

[edit]In gastropods, photosymbiosis can be found in several genera.

The species Strombus gigas hosts Symbiodinium which is acquired during the larval stage, at which point it is a mutualistic relationship.[44] However, during the adult stage, Symbiodinium becomes parasitic as the shell prevents photosynthesis.[45]

Another group of gastropods, heterobranch sea slugs, have two different systems for symbiosis. The first, Nudibranchia, acquire their symbionts through feeding on cnidarian prey that are in symbiotic relationships.[46] In Nudibranchs, photosymbiosis has evolved twice, in Melibe and Aeolidida.[47] In Aeolidida it is likely there have been several gains and losses of photosymbiosis as most genera include both photosymbiotic and non-photosymbiotic species.[48] The second, Sacoglossa, removes chloroplasts from macroalgae when feeding and sequesters them into their digestive tract at which point they are called kleptoplasts.[49] Whether these kleptoplasts maintain their photosynthetic capabilities depends on the host species ability to digest them properly.[50] In this group, functional kleptoplasy has been acquired twice, in Costasiellidae and Plakobranchacea.[51]

Chordates

[edit]Photosymbiosis is relatively uncommon in chordate species.[52] One such example of photosymbiosis is in ascidians, the sea squirts. In the genus Didemnidae, 30 species establish symbiotic relationships.[53] The photosynthetic ascidians are associated with cyanobacteria in the genus of Prochloron as well as, in some cases, the species Synechocystis trididemni.[54] The 30 species with a symbiotic relationship span four genera where the congeners are primarily non-symbiotic, suggesting multiple origins of photosymbiosis in ascidians.[55]

In addition to sea squirts, embryos of some amphibian species (Ambystoma maculatum, Ambystoma gracile, Ambystoma jeffersonium, Ambystoma trigrinum, Hynobius nigrescens, Lithobates sylvaticus, and Lithobates aurora) form symbiotic relationships with the green alga in the genus of Oophila.[56][57][58] This algae is present in the egg masses of the species, causing them to appear green and providing oxygen and carbohydrates to the embryos.[59] Similarly, little is known about the evolution of symbiosis in amphibians, but there appears to be multiple origins.

Protists

[edit]Photosymbiosis has evolved multiple times in the protist taxa Ciliophora, Foraminifera, Radiolaria, Dinoflagellata, and diatoms.[60] Foraminifera and Radiolaria are planktonic taxa that serve as primary producers in open ocean communities.[61] Photosynthetic plankton species associate with the symbiotes of dinoflagellates, diatoms, rhodophytes, chlorophytes, and cyanophytes that can be transferred both vertically and horizontally.[62] In Foraminifera, benthic species will either have a symbiotic relationship with Symbiodinium or retain the chloroplasts present in algal prey species.[63] The planktonic species of Foraminifera associate primarily with Pelagodinium.[64] These species are often considered indicator species due to their bleaching in response to environmental stressors.[65] In the Radiolarian group Acantharia, photosynthetic species inhabit surface waters whereas non-photosynthetic species inhabit deeper waters. Photosynthetic Acantharia are associated with similar microalgae as the Foraminifera groups, but were also found to be associated with Phaeocystis, Heterocapsa, Scrippsiella, and Azadinium which were not previously known to be involved in photosynthetic relationships.[66] In addition, several of the species present in symbiotic relationships with Acantharia were oftentimes identical to the free-living species, suggesting horizontal transfer of symbiotes.[67] This provides insight into the evolutionary patterns responsible for these symbiotic relationships, suggesting that the selection for symbiosis is relatively weak and symbiosis is likely a result of the adaptive capacity of the host plankton species.

References

[edit]- ^ "photosymbiosis". Oxford Reference.

- ^ Gault J, Bentlage B, Huang D, Kerr A (2021). "Lineage-specific variation in the evolutionary stability of coral photosymbiosis". Science Advances. 7 (39): eabh4243. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.4243G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh4243. PMC 8457658. PMID 34550731.

- ^ Decelle, Johan (2013). "New perspectives on the functioning and evolution of photosymbiosis in plankton: Mutualism or parasitism?". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 6 (4): e24560. doi:10.4161/cib.24560. PMC 3742057. PMID 23986805.

- ^ Enrique-Navarro A, Huertas E, Flander-Putrle V, Bartual A, Navarro G, Ruiz J, Malej A, Prieto L. "Living Inside a Jellyfish: The Symbiosis Case Study of Host-Specialized Dinoflagellates, "Zooxanthellae", and the Scyphozoan Cotylorhiza tuberculata". Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Gault J, Bentlage B, Huang D, Kerr A (2021). "Lineage-specific variation in the evolutionary stability of coral photosymbiosis". Science Advances. 7 (39): eabh4243. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.4243G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh4243. PMC 8457658. PMID 34550731.

- ^ Stanley Jr G, Lipps J (2011). "Photosymbiosis: The Driving Force for Reef Success and Failure". The Paleontological Society Papers. 17: 33–59. doi:10.1017/S1089332600002436. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Decelle, Johan (2013). "New perspectives on the functioning and evolution of photosymbiosis in plankton: Mutualism or parasitism?". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 6 (4): e24560. doi:10.4161/cib.24560. PMC 3742057. PMID 23986805.

- ^ Basic Biology (18 March 2016). "Bacteria".

- ^ a b c Spribille, Toby; Resl, Philipp; Stanton, Daniel E.; Tagirdzhanova, Gulnara (June 2022). "Evolutionary biology of lichen symbioses". New Phytologist. 234 (5): 1566–1582. doi:10.1111/nph.18048. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 35302240.

- ^ Grube, Martin; Cernava, Tomislav; Soh, Jung; Fuchs, Stephan; Aschenbrenner, Ines; Lassek, Christian; Wegner, Uwe; Becher, Dörte; Riedel, Katharina; Sensen, Christoph W; Berg, Gabriele (2015-02-01). "Exploring functional contexts of symbiotic sustain within lichen-associated bacteria by comparative omics". The ISME Journal. 9 (2): 412–424. Bibcode:2015ISMEJ...9..412G. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.138. ISSN 1751-7362. PMC 4303634. PMID 25072413.

- ^ a b Miadlikowska, Jolanta; Kauff, Frank; Högnabba, Filip; Oliver, Jeffrey C.; Molnár, Katalin; Fraker, Emily; Gaya, Ester; Hafellner, Josef; Hofstetter, Valérie; Gueidan, Cécile; Otálora, Mónica A.G.; Hodkinson, Brendan; Kukwa, Martin; Lücking, Robert; Björk, Curtis (October 2014). "A multigene phylogenetic synthesis for the class Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota): 1307 fungi representing 1139 infrageneric taxa, 317 genera and 66 families". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 79: 132–168. Bibcode:2014MolPE..79..132M. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.04.003. hdl:11336/11976. PMC 4185256. PMID 24747130.

- ^ Yahr, Rebecca; Vilgalys, Rytas; DePriest, Paula T. (September 2006). "Geographic variation in algal partners of Cladonia subtenuis (Cladoniaceae) highlights the dynamic nature of a lichen symbiosis". New Phytologist. 171 (4): 847–860. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01792.x. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 16918555.

- ^ Sanders, William B.; Masumoto, Hiroshi (September 2021). "Lichen algae: the photosynthetic partners in lichen symbioses". The Lichenologist. 53 (5): 347–393. doi:10.1017/S0024282921000335. ISSN 0024-2829.

- ^ a b Nelsen, Matthew P.; Lücking, Robert; Boyce, C. Kevin; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten; Ree, Richard H. (September 2020). "The macroevolutionary dynamics of symbiotic and phenotypic diversification in lichens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (35): 21495–21503. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11721495N. doi:10.1073/pnas.2001913117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7474681. PMID 32796103.

- ^ a b Melo Clavijo, Jenny; Donath, Alexander; Serôdio, João; Christa, Gregor (November 2018). "Polymorphic adaptations in metazoans to establish and maintain photosymbioses". Biological Reviews. 93 (4): 2006–2020. doi:10.1111/brv.12430. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 29808579.

- ^ de Oliveira, Bruno Francesco Rodrigues; Freitas-Silva, Jéssyca; Sánchez-Robinet, Claudia; Laport, Marinella Silva (December 2020). "Transmission of the sponge microbiome: moving towards a unified model". Environmental Microbiology Reports. 12 (6): 619–638. Bibcode:2020EnvMR..12..619D. doi:10.1111/1758-2229.12896. ISSN 1758-2229. PMID 33048474.

- ^ Hudspith, Meggie; de Goeij, Jasper M; Streekstra, Mischa; Kornder, Niklas A; Bougoure, Jeremy; Guagliardo, Paul; Campana, Sara; van der Wel, Nicole N; Muyzer, Gerard; Rix, Laura (2022-06-02). "Harnessing solar power: photoautotrophy supplements the diet of a low-light dwelling sponge". The ISME Journal. 16 (9): 2076–2086. Bibcode:2022ISMEJ..16.2076H. doi:10.1038/s41396-022-01254-3. ISSN 1751-7362. PMC 9381825. PMID 35654830.

- ^ Muscatine, Leonard; Goiran, Claire; Land, Lynton; Jaubert, Jean; Cuif, Jean-Pierre; Allemand, Denis (February 2005). "Stable isotopes (δ 13 C and δ 15 N) of organic matrix from coral skeleton". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (5): 1525–1530. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408921102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 547863. PMID 15671164.

- ^ Weis, Virginia M. (2008-10-01). "Cellular mechanisms of Cnidarian bleaching: stress causes the collapse of symbiosis". Journal of Experimental Biology. 211 (19): 3059–3066. doi:10.1242/jeb.009597. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 18805804.

- ^ Padilla-Gamiño, Jacqueline L.; Pochon, Xavier; Bird, Christopher; Concepcion, Gregory T.; Gates, Ruth D. (2012-06-06). "From Parent to Gamete: Vertical Transmission of Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) ITS2 Sequence Assemblages in the Reef Building Coral Montipora capitata". PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e38440. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738440P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038440. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3368852. PMID 22701642.

- ^ van Oppen, Madeleine J. H.; Medina, Mónica (2020-09-28). "Coral evolutionary responses to microbial symbioses". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 375 (1808): 20190591. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0591. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 7435167. PMID 32772672.

- ^ Stanley, G. D.; van de Schootbrugge, B. (2009), van Oppen, Madeleine J. H.; Lough, Janice M. (eds.), "The Evolution of the Coral–Algal Symbiosis", Coral Bleaching, vol. 205, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 7–19, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69775-6_2, ISBN 978-3-540-69774-9, retrieved 2024-05-08

- ^ Paps, J.; Baguna, J.; Riutort, M. (2009-07-14). "Bilaterian Phylogeny: A Broad Sampling of 13 Nuclear Genes Provides a New Lophotrochozoa Phylogeny and Supports a Paraphyletic Basal Acoelomorpha". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (10): 2397–2406. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp150. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 19602542.

- ^ SHANNON, THOMAS; ACHATZ, JOHANNES G. (2007-07-12). "Convolutriloba macropyga sp. nov., an uncommonly fecund acoel (Acoelomorpha) discovered in tropical aquaria". Zootaxa. 1525 (1). doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1525.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ^ Ax, P. (April 1970). "Neue Pogaina-Arten (Turbellaria, Dalyellioda) mit Zooxanthellen aus dem Mesopsammal der Nordsee- und Mittelmeerküste". Marine Biology. 5 (4): 337–340. Bibcode:1970MarBi...5..337A. doi:10.1007/bf00346899. ISSN 0025-3162.

- ^ Gschwentner, Robert; Mueller, Johann; Ladurner, Peter; Rieger, Reinhard; Tyler, Seth (2003-02-12). "Unique patterns of longitudinal body-wall musculature in the Acoela (Plathelminthes): the ventral musculature of Convolutriloba longifissura". Zoomorphology. 122 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1007/s00435-003-0074-3. ISSN 0720-213X.

- ^ Serôdio, João; Silva, Raquel; Ezequiel, João; Calado, Ricardo (2010-07-14). "Photobiology of the symbiotic acoel flatwormSymsagittifera roscoffensis: algal symbiont photoacclimation and host photobehaviour". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 91 (1): 163–171. doi:10.1017/s0025315410001001. ISSN 0025-3154.

- ^ Taylor, D. L. (May 1971). "On the symbiosis betweenAmphidinium klebsii[Dinophyceae] andAmphiscolops langerhansi[Turbellaria: Acoela]". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 51 (2): 301–313. Bibcode:1971JMBUK..51..301T. doi:10.1017/s0025315400031799. ISSN 0025-3154.

- ^ Lopes, Rubens Mendes; Silveira, Marina (July 1994). "Symbiosis between a pelagic flatworm and a dinoflagellate from a tropical area: structural observations". Hydrobiologia. 287 (3): 277–284. doi:10.1007/bf00006376. ISSN 0018-8158.

- ^ Barneah, Orit; Brickner, Itzchak; Hooge, Matthew; Weis, Virginia M.; Benayahu, Yehuda (2007-08-14). "First evidence of maternal transmission of algal endosymbionts at an oocyte stage in a triploblastic host, with observations on reproduction inWaminoa brickneri(Acoelomorpha)". Invertebrate Biology. 126 (2): 113–119. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7410.2007.00082.x. ISSN 1077-8306.

- ^ Hikosaka-Katayama, Tomoe; Koike, Kanae; Yamashita, Hiroshi; Hikosaka, Akira; Koike, Kazuhiko (September 2012). "Mechanisms of Maternal Inheritance of Dinoflagellate Symbionts in the Acoelomorph WormWaminoa litus". Zoological Science. 29 (9): 559–567. doi:10.2108/zsj.29.559. ISSN 0289-0003. PMID 22943779.

- ^ Apelt, G. (June 1969). "Die Symbiose zwischen dem acoelen Turbellar Convoluta convoluta und Diatomeen der Gattung Licmophora". Marine Biology. 3 (2): 165–187. Bibcode:1969MarBi...3..165A. doi:10.1007/bf00353437. ISSN 0025-3162.

- ^ Ax, Peter; Apelt, Gieselbert (1965). "Die ?Zooxanthellen? vonConvoluta convoluta (Turbellaria Acoela) entstehen aus Diatomeen". Die Naturwissenschaften. 52 (15): 444–446. doi:10.1007/bf00627043. ISSN 0028-1042.

- ^ Melo Clavijo, Jenny; Donath, Alexander; Serôdio, João; Christa, Gregor (November 2018). "Polymorphic adaptations in metazoans to establish and maintain photosymbioses". Biological Reviews. 93 (4): 2006–2020. doi:10.1111/brv.12430. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 29808579.

- ^ Ax, P. (April 1970). "Neue Pogaina-Arten (Turbellaria, Dalyellioda) mit Zooxanthellen aus dem Mesopsammal der Nordsee- und Mittelmeerküste". Marine Biology. 5 (4): 337–340. Bibcode:1970MarBi...5..337A. doi:10.1007/bf00346899. ISSN 0025-3162.

- ^ Ax, P. (April 1970). "Neue Pogaina-Arten (Turbellaria, Dalyellioda) mit Zooxanthellen aus dem Mesopsammal der Nordsee- und Mittelmeerküste". Marine Biology. 5 (4): 337–340. Bibcode:1970MarBi...5..337A. doi:10.1007/bf00346899. ISSN 0025-3162.

- ^ Douglas, Angela E. (June 1987). "Experimental studies on symbioticChlorellain the Neorhabdocoel TurbellariaDalyellia viridisandTyphloplana viridata". British Phycological Journal. 22 (2): 157–161. doi:10.1080/00071618700650181. ISSN 0007-1617.

- ^ Melo Clavijo, Jenny; Donath, Alexander; Serôdio, João; Christa, Gregor (November 2018). "Polymorphic adaptations in metazoans to establish and maintain photosymbioses". Biological Reviews. 93 (4): 2006–2020. doi:10.1111/brv.12430. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 29808579.

- ^ HERNAWAN, UDHI EKO (2008-12-06). "REVIEW: Symbiosis between the Giant Clams (Bivalvia: Cardiidae) and Zooxanthellae (Dinophyceae)". Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity. 9 (1). doi:10.13057/biodiv/d090112. ISSN 2085-4722.

- ^ Septiadi, Angga; Hernawan, Hernawan; Widiastuti, Widiastuti (2019-11-10). Journal Sport Area. 4 (2): 285. doi:10.25299/sportarea.2019.vol4(2).1803. ISSN 2528-584X https://doi.org/10.25299%2Fsportarea.2019.vol4%282%29.1803.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ PARDY, R. L. (June 1980). "SYMBIOTIC ALGAE AND14C INCORPORATION IN THE FRESHWATER CLAM,ANODONTA". The Biological Bulletin. 158 (3): 349–355. doi:10.2307/1540861. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1540861.

- ^ PARDY, R. L. (June 1980). "SYMBIOTIC ALGAE AND14C INCORPORATION IN THE FRESHWATER CLAM,ANODONTA". The Biological Bulletin. 158 (3): 349–355. doi:10.2307/1540861. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1540861.

- ^ Maruyama, T.; Ishikura, M.; Yamazaki, S.; Kanai, S. (August 1998). "Molecular Phylogeny of Zooxanthellate Bivalves". The Biological Bulletin. 195 (1): 70–77. doi:10.2307/1542777. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1542777. PMID 9739550.

- ^ Drewett, Peter L. (2014-03-04), "Strombus gigas (Queen Conch)", Encyclopedia of Caribbean Archaeology, University Press of Florida, pp. 329–330, doi:10.2307/j.ctvx1hst1.172, retrieved 2024-05-08

- ^ Banaszak, Anastazia T.; García Ramos, Maribel; Goulet, Tamar L. (November 2013). "The symbiosis between the gastropod Strombus gigas and the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium: An ontogenic journey from mutualism to parasitism". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 449: 358–365. Bibcode:2013JEMBE.449..358B. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2013.10.027. ISSN 0022-0981.

- ^ BURGHARDT, I (2008-03-27). "Symbiosis between Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) and various taxa of Nudibranchia (Mollusca: Gastropoda), with analyses of long-term retention". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 8 (1): 66–76. Bibcode:2008ODivE...8...66B. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2007.01.001. ISSN 1439-6092.

- ^ Melo Clavijo, Jenny; Donath, Alexander; Serôdio, João; Christa, Gregor (November 2018). "Polymorphic adaptations in metazoans to establish and maintain photosymbioses". Biological Reviews. 93 (4): 2006–2020. doi:10.1111/brv.12430. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 29808579.

- ^ Melo Clavijo, Jenny; Donath, Alexander; Serôdio, João; Christa, Gregor (November 2018). "Polymorphic adaptations in metazoans to establish and maintain photosymbioses". Biological Reviews. 93 (4): 2006–2020. doi:10.1111/brv.12430. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 29808579.

- ^ Händeler, Katharina; Grzymbowski, Yvonne P; Krug, Patrick J; Wägele, Heike (2009). "Functional chloroplasts in metazoan cells - a unique evolutionary strategy in animal life". Frontiers in Zoology. 6 (1): 28. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-6-28. ISSN 1742-9994. PMC 2790442. PMID 19951407.

- ^ Christa, Gregor; Gould, Sven B.; Franken, Johanna; Vleugels, Manja; Karmeinski, Dario; Händeler, Katharina; Martin, William F.; Wägele, Heike (2014-05-23). "Functional kleptoplasty in a limapontioidean genus: phylogeny, food preferences and photosynthesis inCostasiella, with a focus onC. ocellifera(Gastropoda: Sacoglossa)". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 80 (5): 499–507. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyu026. ISSN 0260-1230.

- ^ Christa, Gregor; Gould, Sven B.; Franken, Johanna; Vleugels, Manja; Karmeinski, Dario; Händeler, Katharina; Martin, William F.; Wägele, Heike (December 2014). "Functional kleptoplasty in a limapontioidean genus: phylogeny, food preferences and photosynthesis in Costasiella , with a focus on C. ocellifera (Gastropoda: Sacoglossa)". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 80 (5): 499–507. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyu026. ISSN 0260-1230.

- ^ Melo Clavijo, Jenny; Donath, Alexander; Serôdio, João; Christa, Gregor (November 2018). "Polymorphic adaptations in metazoans to establish and maintain photosymbioses". Biological Reviews. 93 (4): 2006–2020. doi:10.1111/brv.12430. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 29808579.

- ^ Hirose, Euichi (2014-04-15). "Ascidian photosymbiosis: Diversity of cyanobacterial transmission during embryogenesis". Genesis. 53 (1): 121–131. doi:10.1002/dvg.22778. ISSN 1526-954X. PMID 24700539.

- ^ Hirose, Euichi (2014-04-15). "Ascidian photosymbiosis: Diversity of cyanobacterial transmission during embryogenesis". Genesis. 53 (1): 121–131. doi:10.1002/dvg.22778. ISSN 1526-954X. PMID 24700539.

- ^ Yokobori, Shin-ichi; Kurabayashi, Atsushi; Neilan, Brett A.; Maruyama, Tadashi; Hirose, Euichi (July 2006). "Multiple origins of the ascidian-Prochloron symbiosis: Molecular phylogeny of photosymbiotic and non-symbiotic colonial ascidians inferred from 18S rDNA sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (1): 8–19. Bibcode:2006MolPE..40....8Y. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.025. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 16531073.

- ^ Gilbert, Perry W. (July 1944). "The Alga-Egg Relationship in Ambystoma Maculatum, A Case of Symbiosis". Ecology. 25 (3): 366–369. Bibcode:1944Ecol...25..366G. doi:10.2307/1931284. ISSN 0012-9658. JSTOR 1931284.

- ^ Muto, Kiyoaki; Nishikawa, Kanto; Kamikawa, Ryoma; Miyashita, Hideaki (April 2017). "Symbiotic green algae in eggs of Hynobius nigrescens, an amphibian endemic to Japan". Phycological Research. 65 (2): 171–174. doi:10.1111/pre.12173. ISSN 1322-0829.

- ^ Kerney, Ryan; Kim, Eunsoo; Hangarter, Roger P.; Heiss, Aaron A.; Bishop, Cory D.; Hall, Brian K. (2011-04-04). "Intracellular invasion of green algae in a salamander host". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (16): 6497–6502. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.6497K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018259108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3080989. PMID 21464324.

- ^ Marco, Adolfo; Blaustein, Andrew R. (December 2000). "Symbiosis with Green Algae Affects Survival and Growth of Northwestern Salamander Embryos". Journal of Herpetology. 34 (4): 617. doi:10.2307/1565283. hdl:10261/48328. JSTOR 1565283.

- ^ Decelle, Johan; Colin, Sébastien; Foster, Rachel A. (2015), "Photosymbiosis in Marine Planktonic Protists", Marine Protists, Tokyo: Springer Japan, pp. 465–500, doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55130-0_19, ISBN 978-4-431-55129-4, retrieved 2024-05-08

- ^ Decelle, Johan (2013-07-30). "New perspectives on the functioning and evolution of photosymbiosis in plankton: Mutualism or parasitism?". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 6 (4): e24560. doi:10.4161/cib.24560. ISSN 1942-0889. PMC 3742057. PMID 23986805.

- ^ Fay, S. A.; Weber, M. X.; Lipps, J. H. (2009-06-05). "The distribution of Symbiodinium diversity within individual host foraminifera". Coral Reefs. 28 (3): 717–726. Bibcode:2009CorRe..28..717F. doi:10.1007/s00338-009-0511-y. ISSN 0722-4028.

- ^ Decelle, Johan; Colin, Sébastien; Foster, Rachel A. (2015), "Photosymbiosis in Marine Planktonic Protists", Marine Protists, Tokyo: Springer Japan, pp. 465–500, doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55130-0_19, ISBN 978-4-431-55129-4, retrieved 2024-05-08

- ^ Decelle, Johan; Colin, Sébastien; Foster, Rachel A. (2015), "Photosymbiosis in Marine Planktonic Protists", Marine Protists, Tokyo: Springer Japan, pp. 465–500, doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55130-0_19, ISBN 978-4-431-55129-4, retrieved 2024-05-08

- ^ Hallock, Pamela; Williams, D. E; Fisher, E. M; Toler, S. K (2006-01-01). "Bleaching in foraminifera with algal symbionts: implications for reef monitoring and risk asessment". Anuário do Instituto de Geociências. 29 (1): 108–128. doi:10.11137/2006_1_108-128. ISSN 1982-3908.

- ^ Decelle, Johan (2013-07-30). "New perspectives on the functioning and evolution of photosymbiosis in plankton: Mutualism or parasitism?". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 6 (4): e24560. doi:10.4161/cib.24560. ISSN 1942-0889. PMC 3742057. PMID 23986805.

- ^ Decelle, Johan (2013-07-30). "New perspectives on the functioning and evolution of photosymbiosis in plankton: Mutualism or parasitism?". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 6 (4): e24560. doi:10.4161/cib.24560. ISSN 1942-0889. PMC 3742057. PMID 23986805.