Cornu aspersum

| Cornu aspersum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Garden snail (Cornu aspersum) on Limonium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Order: | Stylommatophora |

| Family: | Helicidae |

| Subfamily: | Helicinae |

| Tribe: | Thebini |

| Genus: | Cornu |

| Species: | C. aspersum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cornu aspersum (O. F. Müller, 1774)[2]

| |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Cornu aspersum (syn. Helix aspersa, Cryptomphalus aspersus), known by the common name garden snail, is a species of land snail in the family Helicidae, which includes some of the most familiar land snails. Of all terrestrial molluscs, this species may well be the most widely known. It was classified under the name Helix aspersa for over two centuries, but the prevailing classification now places it in the genus Cornu.

The snail is relished as a food item in some areas, but it is also widely regarded as a pest in gardens and in agriculture, especially in regions where it has been introduced accidentally, and where snails are not usually considered to be a menu item.

Description

[edit]

The adult bears a hard, thin calcareous shell 25–40 millimetres (1–1+5⁄8 in) in diameter and 25–35 millimetres (1–1+3⁄8 in) high, with four or five whorls. The shell is variable in coloring and shade of color, but generally it has a reticulated pattern of dark brown, brownish-golden, or chestnut with yellow stripes, flecks, or streaks (characteristically interrupted brown colour bands). The aperture is large and characteristically oblique, its margin in adults is whitish and reflected.

The body is soft and slimy, brownish-grey, and able to be retracted entirely into the shell, which the animal does when inactive or threatened. When injured or badly irritated the snail produces a defensive froth of mucus that might repel some enemies or overwhelm aggressive small ants and the like. It has no operculum; during dry or cold weather it seals the aperture of the shell with a thin membrane of dried mucus; the term for such a membrane is epiphragm. The epiphragm helps the snail retain moisture and protects it from small predators such as some ants.

The snail's quiescent periods during heat and drought are known as aestivation; its quiescence during winter is known as overwintering. When overwintering, Cornu aspersum avoids the formation of ice in its tissues by altering the osmotic components of its blood (or haemolymph); this permits it to survive temperatures as low as −5 °C (23 °F).[4] During aestivation, the mantle collar has the ability to change its permeability to water.[5] The snail also has an osmoregulatory mechanism that prevents excessive absorption of water during hibernation. These mechanisms allow Cornu aspersum to avoid either fatal desiccation or hydration during months of either kind of quiescence.

During times of activity the snail's head and "foot" emerge. The head bears four tentacles; the upper two are larger and bear eye-like light sensors, and the lower two are tactile and olfactory sense organs. The snail extends the tentacles by internal pressure of body fluids, and retracts all four tentacles into the head by invagination when threatened or otherwise retreating into its shell. The mouth is located beneath the tentacles, and contains a chitinous radula with which the snail scrapes and manipulates food particles.

The shell of Cornu aspersum is almost always right-coiled, but exceptional left-coiled specimens are also known; see Jeremy (snail) for an example.

Taxonomy

[edit]The accepted name of the species was long considered to be Helix aspersa, a member of the genus Helix, like the Roman snail Helix pomatia. However, in a number of publications since 1990,[6] it has instead been placed in various genera previously considered as subgenera of Helix. One such genus is Cornu, which is appropriate if the species is considered as congeneric with the species previously known as Helix aperta.[7][8] Then the name would be Cornu aspersum.[9][10][11] Previously there was debate whether Cornu was a valid generic name (because it was first applied to teratological specimens), but a 2015 ruling has confirmed that it is so.[12] Until this was established, Italian research teams and others used the generic name Cantareus instead.[13][14][15][16] Other workers, including Ukrainian and Russian research teams, who regard H. aspersa and H. aperta as being in different genera, call the former Cryptomphalus aspersus.[17][18][19][20]

Analyses based on DNA sequences have now established that C. aspersum and C. aperta share a clade with snails in the genera Otala and Eobania, distinct from the clade containing Helix, so it is no longer tenable to consider them as species of Helix.[21]

Many subspecific varieties have been described on the basis of shell characters (e.g.[22]). The most prominent example nowadays is the subspecies Cornu aspersum maximum (Taylor, 1883),[23] originally described as a large shelled form from Algeria (but perhaps including similar forms from elsewhere). In the recent scientific literature the name has been applied both to large Algerian snails[24] and to a large form found in snail farms.[25] Some Algerian forms are indeed genetically quite distant from the usual, most widespread form, but the large form in snail farms is different again.[26][25] It is also problematic that there was a prior use of the name Helix aspersa maxima unassociated with Algeria.[27] The subspecies maximum is formally considered by some authorities as a junior synonym of Cornu aspersum.[28][29]

Life cycle

[edit]

Like other Pulmonata, individuals are hermaphrodites, producing both male and female gametes. Reproduction is predominantly, and probably exclusively, by outcrossing.[30][31] During a mating session of several hours, two snails exchange sperm reciprocally. H. aspersa snails stab a calcite spine, known as a love dart, into their partner. The mucus coating the love dart contains a chemical that diverts sperm away from being digested. This is important for sperm competition because individuals mate repeatedly and the donated sperm can remain viable for 4 years.[31][32] About 10 days after fertilisation, the snail lays a batch of on average 50 spherical, pearly-white eggs into crevices in the topsoil, or sheltered under stones.[30] In a year it may lay approximately six batches of eggs.[33] The size of the egg is 3 mm.[30]

After snails hatch from the egg, they mature in one or more years. Maturity takes two years in Southern California, while it takes only 10 months in South Africa.[citation needed] In captivity snails can become sexually mature within 3.5 months of hatching, before they stop growing.[30] The lifespan of snails in the wild is typically 2–3 years.[citation needed]

Distribution

[edit]

Cornu aspersum is native to the Mediterranean region and its present range stretches from northwest Africa and Iberia, eastwards to Asia Minor and Egypt,[34] and northwards to Britain.[35]

Cornu aspersum is a typically anthropochorous species; it has been spread to many geographical regions by humans, either deliberately or accidentally. Nowadays, it is cosmopolitan in temperate zones, and has become naturalised in regions with climates that differ from the mediterranean climate in which it evolved.[36][37] Its passive anthropochory is the likeliest explanation for genetic resemblances between allopatric populations. Its anthropochorous spread may have started as early as during the Neolithic Revolution some 8500 BP. Such anthropochory continues, sometimes resulting in locally catastrophic destruction of habitat or crops.[38]

Its increasing non-native distribution includes parts of Europe, such as Bohemia in the Czech Republic since 2008.[39] It is present in Australia, New Zealand, North America, Costa Rica[40] and southern South America.[41] It was introduced to Southern Africa as a food animal by Huguenots in the 18th century, and into California as a food animal in the 1850s; it is now a notorious agricultural pest in both regions, especially in citrus groves and vineyards. Many jurisdictions have quarantines for preventing the importation of the snail in plant matter.[42]

A number of North African endemic forms and subspecies have been described on the basis of shell characters. Cornu aspersum aspersum, in French commonly called the "petit gris", is native to the Mediterranean area and Western Europe, but has been spread widely elsewhere. The name Cornu aspersum maximum has been applied to a large form kept in heliciculture (in French commonly called the "gros gris"), but this is genetically distinct from large Algerian forms earlier given this name.[26]

Ecology

[edit]

Cornu aspersum is a primarily a herbivore. It feeds on numerous types of fruit trees, vegetable crops, rose bushes, garden flowers, and cereals. It also is an omnivorous scavenger that will feed on rotting plant material and on occasion scavenge animal matter, such as crushed snails and worms. Cornu aspersum can obtain the calcium required to build its shell by consuming soil.[43] In turn it is a food source for many other animals, including small mammals, some bird species, lizards, frogs, centipedes, predatory insects such as glowworms in the family Lampyridae, and predatory terrestrial snails.[44] The species may be of use as an indicator of environmental pollution, because it deposits heavy metals, such as lead, in its shell.[45]

Parasites

[edit]Parasites of Cornu aspersum include a number of nematodes.[46][47][48] Metacercariae of various species of the digenean genus Brachylaima have also been reported, and those have potential for being harmful to people because the adults can infect humans.[48] However, the snails are capable of trapping cercariae (trematode larvae) in their shell, thus possibly reducing the intensity of infestation by parasites.[49]

Behavior

[edit]

The snail secretes thixotropic adhesive mucus that permits locomotion by rhythmic waves of contraction passing forward within its muscular foot. Starting from the rear, the contraction of the longitudinal muscle fibres above a small area of the film of mucus causes shear that liquefies the mucus, permitting the tip of the tail to move forward. The contracted muscle relaxes while its immediately anteriad transverse band of longitudinal fibres contract in their turn, repeating the process, which continues forward until it reaches the head. At that point the whole animal has moved forward by the length of the contraction of one of the bands of contraction. However, depending on the length of the animal, several bands of contraction can be in progress simultaneously, so that the resultant speed amounts to the speed imparted by a single wave, multiplied by the number of individual waves passing along simultaneously.[50]

A separate type of wave motion that may be visible from the side enables the snail to conserve mucus when moving over a dry surface. It lifts its belly skin clear of the ground in arches, contacting only one to two thirds of the area it passes over. With suitable lighting the lifting may be seen from the side as illustrated, and the percentage of saving of mucus may be estimated from the area of wet mucus trail dabs that it leaves behind. This type of wave passes backwards at the speed of the snail's forward motion, therefore having a zero velocity with respect to the ground.

An estimate from 1974 for a top speed of 0.03 mph (1.3 cm/s)[51] has become popular.[52][53] However, this estimate has been questioned since in competitions between snails only speeds of 2.4 mm/s have been achieved.[54]

Cornu aspersum has a strong homing instinct, readily returning to a regular hibernation site.[55]

Human relevance

[edit]

The species is known as an agricultural and garden pest, an edible delicacy, and occasionally a household pet. In French cuisine, it is known as petit gris, and is served for instance in Escargot a la Bordelaise. Also in Lleida, a city of Catalonia (Spain), there is a gastronomic festival called L'Aplec del Caragol dedicated to this type of snail, known as bover, and attracts over 200,000 guests every year. From Crete are known a dish called "chochloi mpoumpouristoi" (snails turned upside down), the snails cooked alive in a hot pan, on a thick layer of sea salt. Other dishes with snails are snails with rosemary, etc. The practice of rearing snails for food is known as heliciculture. For purposes of cultivation, the snails are kept in a dark place in a wired cage with dry straw or dry wood. Coppiced wine-grape vines are often used for this purpose. During the rainy period the snails come out of hibernation and release most of their mucus onto the dry wood/straw. The snails are then prepared for cooking. Their texture when cooked is slightly chewy.

Approaches to snail pest control

[edit]There are a variety of snail-control measures that gardeners and farmers use in an attempt to reduce damage to valuable plants. Traditional pesticides are still used, as are many less toxic control options such as concentrated garlic or wormwood solutions. Copper metal is also a snail repellent, and thus a copper band around the trunk of a tree will prevent snails from climbing up and reaching the foliage and fruit. Caffeine has proven surprisingly toxic to snails, to the extent that spent coffee grounds (not decaffeinated) make a safe and immediately effective snail-repellant and even molluscicidal mulch for pot-plants, or for wherever else the supply is adequate.[citation needed]

The decollate snail (Rumina decollata) will capture and eat garden snails, and because of this it has sometimes been introduced as a biological pest control agent.[57] However, this is not without problems, as the decollate snail is just as likely to attack and devour other species of gastropods that may represent a valuable part of the native fauna of the region.

Pharmacological studies

[edit]Cornu aspersum has gained some popularity as the chief ingredient in skin creams and gels (crema/gel de caracol) sold in the US. These creams are promoted as being suitable for use on wrinkles, scars, dry skin, and acne to reduce pigmentation, scarring, and wrinkles.[58]

Secretions of Cornu aspersum produced under stress have skin-regenerative properties because of antioxidant superoxide dismutase and glutathione S-transferase (GSTs) activities. The secretions can stimulate fibroblast proliferation and rearrange the actin cytoskeleton stimulate extracellular matrix assembly and regulation of metalloproteinase activities for regeneration of wounded tissue.[59]

The mucus of Cornu aspersum contains a rich source of substances that can be used to treat biotic human diseases. Nine fractions of compounds with varying molecular weight were purified from the mucus and was tested against gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial strains. Results found three fractions exhibited predominant antibacterial activity against the gram-positive strain.[60]

While further confirmatory research is still needed, potential benefits of the snail extracts or secretion filtrates have been also demonstrated in other disease models in mice, including protective effects against ethanol-induced gastric ulcer[61] and against the progression of Alzheimer's type dementia.[62]

References

[edit]This article incorporates CC-BY-2.0 text from reference.[38]

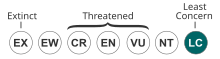

- ^ Neubert, E. (2011). "Cornu aspersum (Europe assessment)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T156890A5012868. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Müller O. F. (1774). Vermivm terrestrium et fluviatilium, seu animalium infusoriorum, helminthicorum, et testaceorum, non marinorum, succincta historia. Volumen alterum. pp. I-XXVI [= 1-36], 1-214, [1-10]. Havniae & Lipsiae. (Heineck & Faber).

- ^ MolluscaBase eds. "Cornu aspersum (O. F. Müller, 1774)". MolluscaBase. LifeWatch Belgium. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Ansart, A.; Vernon, P.; Daguzan, J. (2002). "Elements of cold hardiness in a littoral population of the land snail Cornu aspersum (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 172 (7): 619–625. doi:10.1007/s00360-002-0290-z. PMID 12355230. S2CID 8880986.

- ^ Machin, J (1966). "The evaporation of water from Cornu aspersum IV. Loss from the mantle of the inactive snail". Journal of Experimental Biology. 45 (2): 269–278. doi:10.1242/jeb.45.2.269. PMID 5971994.

- ^ The species was called Cryptomphalus aspersus on p. 244 in the important and widely distributed work Falkner, G. 1990. Binnenmollusken. - pp. 112-280, in: Fechter, R, & Falkner, G.: Weichtiere. Europäische Meeres- und Binnenmollusken. Steinbachs Naturführer 10. -- pp. 1-288. München. (Mosaik).

- ^ "The Cornu problem". The Living World of Mollusks. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ^ Welter-Schultes, F. "Genus taxon summary for Cornu. version 12-01-2014". AnimalBase. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ^ Falkner, G.; Bank, R.A.; Proschwitz, T. von (2001). "Check-list of the non-marine molluscan species-group taxa of the states of northern, Atlantic and central Europe". Heldia. 4 ((1/2)): 1–76.

- ^ Falkner, G.; Ripken, T.E.J.; Falkner, M. (2002). "Mollusques continentaux de France. Liste de référence annotée et bibliographie". Collection Patrimoines Naturels. 52: [1–2], 1–350, [1–3].

- ^ Bank, R.; Falkner, G.; Proschwitz, T. von (2007). "CLECOM-Project. A revised checklist of the non-marine Mollusca of Britain and Ireland". Heldia. 5 (3): 41–72.

- ^ ICZN (2015). "Opinion 2354 (Case 3518). Cornu Born, 1778 (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Helicidae): request for a ruling on the availability of the generic name granted". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 72 (2): 157–158. doi:10.21805/bzn.v72i2.a9. S2CID 85702218.

- ^ Manganelli, G., Bodon, M., Favilli, L. & Giusti, F. 1995. Fascicolo 16. Gastropoda Pulmonata. - pp. 1-60, in: Minelli A., Ruffo, S. & La Posta, S.: Checklist delle specie della fauna italiana. Bologna. (Calderini).

- ^ Giusti, F., Manganelli, G. & Schembri, P. J. 1995. The non-marine molluscs of the Maltese Islands. - pp. 1-608. Torino.

- ^ Neubert, E (1998). "Annotated checklist of the terrestrial and freshwater molluscs of the Arabian Peninsula with descriptions of new species". Fauna of Arabia. 17: 333–461.

- ^ Manganelli, G.; Salomone, N.; Giusti, F. (2005). "A molecular approach to the phylogenetic relationships of the western palaearctic Helicoidea (Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 85 (4): 501–512. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00514.x.

- ^ Sverlova, N. V. (2006). "O rasprostranenii nekotorɨkh vidov nazemnɨkh mollyuskov na territorii Ukrainɨ". Ruthenica. 16 (1/2): 119–139.

- ^ Schileyko, A. A. (2006). "Treatise on recent terrestrial pulmonate molluscs, Part 13. Helicidae, Pleurodontidae, Polygyridae, Ammonitellidae, Oreohelicidae, Thysanophoridae". Ruthenica. 2 (10): 1765–1906.

- ^ Egorov, R. (2008). Treasure of Russian shells. Supplement 5. Illustrated catalogue of the recent terrestrial molluscs of Russia and adjacent regions. Moscow. pp. 1–179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sysoev, A.; Schileyko, A.A. (2009). Land snails and slugs of Russia and adjacent countries. Sofia: Pensoft. pp. 1-312, figs 1-142. ISBN 9789546424747.

- ^ Nordsieck, H. (2017). "Chapter 9: Systematic position of Helix aspersa Müller 1774 (Helicinae, Helicidae)". Pulmonata, Stylommatophora, Helicoidea: systematics with comments. Harxheim: ConchBooks. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9783939767817.

- ^ Taylor, J.W. (1913). Monograph of the land and freshwater Mollusca of the British Isles. Leeds: Taylor Brothers. pp. 236–273.

- ^ Taylor, J.W. (1883). "Life histories of British Helices: Helix (Pomatia) aspersa Müll". Journal of Conchology. 4: 89–105.

- ^ Madec, L.; Guiller, A. (1993). "Observations on distal genitalia and mating activity in three conchologically distinct forms of the land snail Helix aspersa Müller". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 59 (4): 455–460. doi:10.1093/mollus/59.4.455.

- ^ a b Guiller, Annie; Martin, Marie-Claire; Hiraux, Céline; Madec, Luc; Sorci, Gabriele (5 December 2012). "Tracing the invasion of the Mediterranean land snail Cornu aspersum aspersum becoming an agricultural and garden pest in areas recently introduced". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e49674. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749674G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049674. PMC 3515588. PMID 23227148.

- ^ a b Guiller, A.; Coutellec-Vreto, M. A.; Madec, L.; Deunff, J. (2001). "Evolutionary history of the land snail Helix aspersa in the Western Mediterranean: preliminary results inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences". Molecular Ecology. 10 (1): 81–87. Bibcode:2001MolEc..10...81G. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01145.x. PMID 11251789. S2CID 23678042.

- ^ Parfitt (1874). "The Fauna of Devon. Part X. Conchology". Transactions of the Devonshire Association: 567–640.

- ^ MolluscaBase. "Helix aspersa var. maxima Parfitt, 1874". MolluscaBase. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ MolluscaBase. "Helix aspersa var. maxima Taylor, 1883". MolluscaBase. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Herzberg, Fred; Herzberg, Anne (1962). "Observations on reproduction in Helix aspersa". The American Midland Naturalist. 68 (2): 297–306. doi:10.2307/2422735. ISSN 0003-0031. JSTOR 2422735.

- ^ a b Garefalaki, M.-E.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Abatzopoulos, T. J.; Staikou, A. (May 2010). "The outcome of sperm competition is affected by behavioural and anatomical reproductive traits in a simultaneously hermaphroditic land snail". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 23 (5): 966–976. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.01964.x. PMID 20298442.

- ^ Rogers, David; Chase, Ronald (1 July 2001). "Dart receipt promotes sperm storage in the garden snail Helix aspersa". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 50 (2): 122–127. doi:10.1007/s002650100345. S2CID 813656.

- ^ Bezemer, T.M.; Knight, K.J. (2001). "Unpredictable responses of garden snail Helix aspersa populations to climate change". Acta Oecologica. 22 (4): 201–208. Bibcode:2001AcO....22..201B. doi:10.1016/s1146-609x(01)01116-x.

- ^ Commonwealth of Australia. 2002 (April) Citrus Imports from the Arab Republic of Egypt. A Review Under Existing Import Conditions for Citrus from Israel Archived 2009-01-09 at the Wayback Machine. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Australia. Caption: Gastropods, page 12 and Appendix 2.

- ^ Kerney, M. P. (1999). Atlas of the land and freshwater molluscs of Britain and Ireland. Colchester, Essex: Harley Books. ISBN 978-0-946589-48-7.

- ^ Arkive: Helix aspersa Archived 2008-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pfleger, V. & Chatfield, J. (1983). A guide to snails of Britain and Europe. Hamlyn, London.

- ^ a b Annie Guiller, A.; Madec, L. (2010). "Historical biogeography of the land snail Cornu aspersum: a new scenario inferred from haplotype distribution in the Western Mediterranean basin:". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-18. PMC 2826328. PMID 20089175.

- ^ Juřičková L. & Kapounek F. (18 November 2009) "Helix (Cornu) aspersa (O.F. Müller, 1774) (Gastropoda: Helicidae) in the Czech Republic". Malacologica Bohemoslovaca 8: 53-55. PDF.

- ^ Barrientos, Zaidett (2003). "Lista de especies de moluscos terrestres (Archaeogastropoda, Mesogastropoda, Archaeopulmonata, Stylommatophora, Soleolifera) informadas para Costa Rica". Revista de Biología Tropical. 51: 293–304.

- ^ "brown garden snail - Cornu asperum (Müller)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "USDA grazing systems and alternative livestock breeds". Archived from the original on 2014-06-23. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ^ Smith, P.N.; Boomer, S.M.; Baltzley, M.J. (2019). "Faecal microbiota dynamics in Cornu aspersum during dietary change and antibiotic challenge". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 85 (3): 327–335. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyz016.

- ^ Fisher, TW; Orth, RE; Swanson, SC (1980). "Snail against snail". California Agriculture. 34 (11): 18–20.

- ^ Beeby, A.; Richmond, L. (1989). "The shell as a site of lead deposition in Cornu aspersum". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 18: 623–628. doi:10.1007/bf01055031. S2CID 95091766.

- ^ Morand, S.; Petter, A. J. (1986). "Nemhelix bakeri n.gen., n.sp. (Nematoda: Cosmocercinae) parasite de l'appareil génital de Helix aspersa (Gastropoda: Helicidae) en France". Canadian Journal of Zoology (in French). 64 (9): 2008–2011. doi:10.1139/z86-303.

- ^ Morand, S (1988). "Cycle évolutif du Nemhelix bakeri Morand et Petter (Nematoda, Cosmocercidae), parasite de l'appareil génital de l'Helix aspersa Müller (Gastropoda, Helicidae)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 66 (8): 1796–1802. doi:10.1139/z88-260.

- ^ a b Gérard, Claudia; Ansart, Armelle; Decanter, Nolwenn; Martin, Marie-Claire; Dahirel, Maxime (2020). "Brachylaima spp. (Trematoda) parasitizing Cornu aspersum (Gastropoda) in France with potential risk of human consumption". Parasite. 27: 15. doi:10.1051/parasite/2020012. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 7069358. PMID 32167465.

- ^ Gérard, Claudia; De Tombeur, Youna; Dahirel, Maxime; Ansart, Armelle (2023). "Land snails can trap trematode cercariae in their shell: Encapsulation as a general response against parasites?". Parasite. 30: 1. doi:10.1051/parasite/2023001. PMC 9879143. PMID 36656045.

- ^ Chan, Brian; Balmforth, N. J.; Hosoi, A. E. (2005). "Building a better snail: Lubrication and adhesive locomotion". Phys. Fluids. 17 (11): 113101–113101–10. Bibcode:2005PhFl...17k3101C. doi:10.1063/1.2102927.

- ^ Willoughby, David P. (1974). "Running and jumping". Natural History. 83 (3): 71.

- ^ Yee, Angie (1999). "Speed of a Snail". The Physics Factbook. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012.

- ^ "Speed of a Snail". Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ^ Cameron, R.A.D. (2016). Slugs and snails. Collins New Naturalist Library, Book 133. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780008203498.

- ^ Attia, J (2004). "Behavioural Rhythms of Land Snails in the Field". Biological Rhythm Research. 35 (1–2): 35–41. doi:10.1080/09291010412331313223. S2CID 84522316.

- ^ Garden Snail in Israel, 29 November 2014, retrieved 2022-01-12

- ^ Wilen, Cheryl A.; Flint, Mary Louise. "Pests in Gardens and Landscapes: Snails and Slugs". Institute of Pest Management. University of California Dep. Agriculture and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ^ Liu, Lucy; Sood, Anshum; Steinweg, Stephanie (2017). "Snails and Skin Care—An Uncovered Combination". JAMA Dermatol. 153 (7): 650. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1383. PMID 28700796.

- ^ Brieva, A.; Philips, N.; Tejedor, R.; Guerrero, A.; Pivel, J. P.; Alonso-Lebrero, J. L.; Gonzalez, S. (2008-01-01). "Molecular basis for the regenerative properties of a secretion of the mollusk Cryptomphalus aspersa". Skin Pharmacology and Physiology. 21 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1159/000109084. PMID 17912020. S2CID 21020611.

- ^ Dolashki, Aleksandar; Velkova, Lyudmila; Daskalova, Elmira; Zheleva, N.; Topalova, Yana; Atanasov, Ventseslav; Voelter, Wolfgang; Dolashka, Pavlina (September 2020). "Antimicrobial activities of different fractions from mucus of the Garden Snail Cornu aspersum". Biomedicines. 8 (9): 315. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8090315. ISSN 2227-9059. PMC 7554965. PMID 32872361.

- ^ Gugliandolo, E; Cordaro, M; Fusco, R; Peritore, AF; Siracusa, R; Genovese, T; D'Amico, R; Impellizzeri, D; Di Paola, R; Cuzzocrea, S; Crupi, R (11 February 2021). "Protective effect of snail secretion filtrate against ethanol-induced gastric ulcer in mice". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 3638. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3638G. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83170-8. PMC 7878904. PMID 33574472.

- ^ Tancheva, L; Lazarova, M; Velkova, L; Dolashki, A; Uzunova, D; Minchev, B; Petkova-Kirova, P; Hassanova, Y; Gavrilova, P; Tasheva, K; Taseva, T; Hodzhev, Y; Atanasov, AG; Stefanova, M; Alexandrova, A; Tzvetanova, E; Atanasov, V; Kalfin, R; Dolashka, P (2022). "Beneficial Effects of Snail Helix aspersa Extract in an Experimental Model of Alzheimer's Type Dementia". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 88 (1): 155–175. doi:10.3233/JAD-215693. PMID 35599481. S2CID 248873157.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Helix aspersa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Helix aspersa at Wikimedia Commons

- Helix aspersa at Animalbase taxonomy, short description, distribution, biology, status (threats), images

- Helix aspersa images at Encyclopedia of Life including genitalia drawings

- brown garden snail on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures website

- Canada Agriculture Fact Sheet

- BBC Info Page

- Extreme Close-Up Video of the North American Garden Snail

- University of California Pest Management Guidelines: Brown Garden Snail

- Video of froth protection response of Cornu aspersum

- Zachi Evenor, A video showing a garden snail (Cornu aspersum / Helix aspersa) in action, YouTube, November 9, 2013