Flood myth

The story of a Great Flood sent by a deity or deities to destroy civilization as an act of divine retribution is a widespread theme among many cultural myths. Though it is best known by the Biblical story of Noah, it is also well known in other versions, such as stories of Matsya in the Hindu Puranas, Deucalion in Greek mythology and Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh. A large percentage of the world's cultures past and present have stories of a "great flood" that devastated earlier civilization.

Flood myths in various cultures

Ancient Near East

Sumerian

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

The Sumerian myth of Ziusudra tells how the god Enki warns Ziusudra (meaning "he saw life," in reference to the gift of immortality given him by the gods), king of Shuruppak, of the gods' decision to destroy mankind in a flood - the passage describing why the gods have decided this is lost. Enki instructs Ziusudra to build a large boat - the text describing the instructions is also lost. After a flood of seven days, Ziusudra makes appropriate sacrifices and prostrations to An (sky-god) and Enlil (chief of the gods), and is given eternal life in Dilmun (the Sumerian Eden) by Anu and Enlil.

The Sumerian king list, a genealogy of traditional, legendary and mythological Sumerian kings, also mentions a great flood.

Excavations in Iraq have shown evidence of a flood at Shuruppak about 2,900-2,750 BCE, which extended nearly as far as the city of Kish, whose king Etana, supposedly founded the first Sumerian dynasty after the flood.

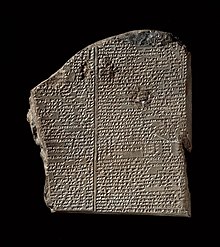

The myth of Ziusudra exists in a single copy, the fragmentary Eridu Genesis, datable by its script to the 17th century BC.[1]

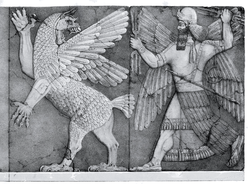

Babylonian (Epic of Gilgamesh)

In the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, toward the end of the He who saw the deep version by Sin-liqe-unninn (tablet 11), there are references to a great flood. But this is a late addition to the Gilgamesh cycle, having been paraphrased or copied verbatim from the Epic of Atrahasis (see below), but in a way that turns a local river flood into an ocean deluge.[2]

The hero Gilgamesh, seeking immortality, searches out Utnapishtim (whose name is a direct translation into Akkadian of the Sumerian Ziusudra) in Dilmun, a kind of paradise on earth. Utnapishtim tells how Ea (equivalent of the Sumerian Enki) warned him of the gods' plan to destroy all life through a great flood and instructed him to build a vessel in which he could save his family, his friends, and his wealth and cattle. After the Deluge the gods repented their action and made Utnapishtim immortal.

Akkadian (Atrahasis Epic)

The Babylonian Atrahasis Epic (written no later than 1700 BC, the name Atrahasis means "exceedingly wise"), gives human overpopulation as the cause for the great flood. After 1200 years of human fertility, the god Enlil felt disturbed in his sleep due to the noise and ruckus caused by the growing population of mankind. He turned for help to the divine assembly who then sent a plague, then a drought, then a famine, and then saline soil, all in an attempt to reduce the numbers of mankind. All these were temporary fixes. 1200 years after each solution, the original problem returned. When the gods decided on a final solution, to send a flood, the god Enki, who had a moral objection to this solution, disclosed the plan to Atrahasis, who then built a survival vessel according to divinely given measurements.

To prevent the other gods from bringing such another harsh calamity, Enki created new solutions in the form of social phenomena such as non-marrying women, barrenness, miscarriages and infant mortality, to help keep the population from growing out of control.

Hebrew

Biblical: The story recorded in the book of Genesis, says that God is "grieved in His heart" by seeing that "every intent of the thoughts of his (man's) heart was only evil continually", and decides to destroy the earth. [3] He selects Noah, who alone with his family is righteous, and instructs him to build an ark, and preserve two of each creature (or seven if they're "clean"). After Noah builds the ark, God makes the "fountains of the great deep burst open" and "the floodgates of the sky" open, making it rain for 40 days and 40 nights. [4] After 150 days, the ark comes to rest on the mountains of Ararat. Four months later the earth was dry enough that they were able to leave the Ark.[5]

Non-Biblical: The 2nd century BC 1st Book of Enoch is a late apocryphal addition to the Hebrew flood legend, in which God sends the Great Flood to rid the earth of the Nephilim, the titanic children of the Grigori, the "sons of God" mentioned in Genesis and of human females.

Asia-Pacific

China

Shanhaijing, "Classic of the Mountain & Seas", ends with the Chinese ruler Da Yu spending ten years to control a deluge whose "floodwaters overflowed [to] heaven". (see: Shanhaijing, chapter 18, second to last paragraph; Anne Birrells translation. note: Nuwa is not mentioned in this translation in the context of a flood)

There are many sources of flood myths in ancient Chinese literature. Some appear to refer to a worldwide deluge:

Shujing, or "Book of History", probably written around 700 BC or earlier, states in the opening chapters that Emperor Yao is facing the problem of flood waters that "reach to the Heavens". This is the backdrop for the intervention of the famous Da Yu, who succeeded in controlling the floods. He went on to found the first Chinese dynasty. (see: Shujing, Part 1 Tang Document, Yao Canon; James Legges translation)

Shiji, Chuci, Liezi, Huainanzi, Shuowen Jiezi, Siku Quanshu, Songsi Dashu, and others, as well as many folk myths, all contain references to a personage named Nüwa. Nuwa is generally represented as a female (although not always) who repairs the broken heavens after a great flood or calamity, and repopulates the world with people. There are many versions of this myth. (see Nüwa for additional detail)

The ancient Chinese civilization concentrated at the bank of Yellow River near present day Xian also believed that the severe flooding along the river bank was caused by dragons (representing gods) living in the river being angered by the mistakes of the people [citation needed].

India

Matsya (Fish in Sanskrit) was the first Avatara of Vishnu.

According to the Matsya Purana and Shatapatha Brahmana (I-8, 1-6), the mantri to the king of pre-ancient Dravida, Satyavata who later becomes known as Manu was washing his hands in a river when a little fish swam into his hands and begged him to save its life. He put it in a jar, which it soon outgrew; he successively moved it to a tank, a river and then the ocean. The fish then warned him that a deluge would occur in a week that would destroy all life. Manu therefore built a boat which the fish towed to a mountaintop when the flood came, and thus he survived along with some "seeds of life" to re-establish life on earth.

Archaeologist MS Dhingra links this myth to a possible meteor impact event in the Indian Ocean. This impact may have occurred in 2084 BC.

Andaman Islands

In myths of the aboriginal tribes inhabitating the Andaman Islands people became remiss of the commands given to them at the creation. Puluga, the god creator, ceased to visit them and then without further warning sent a devastating flood. Only four people survived this flood: two men, Loralola and Poilola, and two women, Kalola and Rimalola. When they landed they found they had lost their fire and all living things had perished. Puluga then recreated the animals and plants but does not seem to have given any further instructions, nor did he return the fire to the survivors[6].

Indonesia

In Batak traditions, the earth rests on a giant snake, Naga-Padoha. One day, the snake tired of its burden and shook the Earth off into the sea. However, the God Batara-Guru saved his daughter by sending a mountain into the sea, and the entire human race descended from her. The Earth was later placed back onto the head of the snake.

Australia

According to the Australian aborigines, in the Dreamtime a huge frog drank all the water in the world and a drought swept across the land. The only way to finish the drought was to make the frog laugh. Animals from all over Australia have gathered together and one by one attempted to make the frog laugh. When finally eel succeeded, the frog opened his sleepy eyes, his big body quivered, his face relaxed, and, at last, he burst into a laugh that sounded like rolling thunder. The water poured from his mouth in a flood. It filled the deepest rivers and covered the land. Only the highest mountain peaks were visible, like islands in the sea. Many men and animals were drowned. The pelican who was blackfellow at that time painted himself with white clay and went from island to island in a great canoe, rescuing other blackfellows. Since that time pelicans have been black and white in remembrance of the Great Flood[7].

Europe

Greek

Greek mythology knows three floods. The flood of Ogyges, the flood of Deucalion and the flood of Dardanus, two of which ending two Ages of Man: the Ogygian Deluge ended the Silver Age, and the flood of Deucalion ended the First Brazen Age.

Ogyges

The Ogygian flood is so called because it occurred in the time of Ogyges[8], a mythical king of Attica. Ogyges is synonymous to "primeval", "primal", "earliest dawn". Others say he was founder and king of Thebes. The Ogygian flood covered the whole world and was so devastating that the country remained without kings until the reign of Cecrops[9]. Plato in his Laws, Book III, estimates that this flood occurred 10,000 years before his time. Also in Timaeus (22) and in Critias (111-112) he describes the "great deluge of all" during the 10th millennium BCE. In addition, the texts report that "many great deluges have taken place during the nine thousand years" since Athens and Atlantis were preeminent[10]. The theory of the flood in the Aegean Basin, proposed that a great flood occurred towards the end of the Miocene. This flood coincides with the end of the last ice age, estimated approximately 10,000 years ago, when the sea level rose as much as 130 metres. The map on the right shows how the region would look 12,000 years ago, when the sea level would have been 100 meters lower than today. The Peloponnese was connected to the mainland and the Corinthian Gulf was not formed. Islands around Attica, such as Aegina, Salamis and Euboea, were part of the mainland. The Cyclades formed a big island known as Aegeis. These geological findings support the hypothesis that the Ogygian Deluge may well be based on a real event.

Deucalion

The Deucalion legend as told by Apollodorus in The Library has some similarity to Noah's Ark: Prometheus advised his son Deucalion to build a chest. All other men perished except for a few who escaped to high mountains. The mountains in Thessaly were parted, and all the world beyond the Isthmus and Peloponnese was overwhelmed. Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha, after floating in the chest for nine days and nights, landed on Parnassus. An older version of the story told by Hellanicus has Deucalion's "ark" landing on Mount Othrys in Thessaly. Another account has him landing on a peak, probably Phouka, in Argolis, later called Nemea. When the rains ceased, he sacrificed to Zeus. Then, at the bidding of Zeus, he threw stones behind him, and they became men, and the stones which Pyrrha threw became women. Appollodorus gives this as an etymology for Greek laos "people" as derived from laas "stone". The Megarians told that Megarus, son of Zeus, escaped Deucalion's flood by swimming to the top of Mount Gerania, guided by the cries of cranes.

Dardanus

According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Dardanus left Pheneus in Arcadia to colonize a land in the North-East Aegean Sea. When the Dardanus' deluge occurred, the land was flooded and the mountain on which he and his family survived, formed the island of Samothrace. He left Samothrace on an inflated skin to the opposite shores of Asia Minor and settled at the foot of Mount Ida. Due to the fear of another flood they didn't built a city, but lived in the open for fifty years. His grandson Tros eventually built a city, which was named Troy after him.

Germanic

In Norse mythology, Bergelmir was a son of Thrudgelmir. He and his wife were the only frost giants to survive the deluge of Bergelmir's grandfather's (Ymir) blood, when Odin and his brothers (Vili and Ve) butchered him. They crawled into a hollow tree trunk and survived, then founded a new race of frost giants.

The mythologist Brian Branston noted the similarities between this myth and an incident described in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, which had traditionally been associated with the Biblical flood, so there was probably a corresponding incident in the broader Germanic mythology as well as in Anglo-Saxon mythology.

Irish

According to the apocryphal history of Ireland Lebor Gabála Érenn, the first inhabitants of Ireland led by Noah's granddaughter Cessair were all except one wiped out by a flood 40 days after reaching the island. Later, after Partholon's and Nemed's people reached the island, another flood rose and killed all but thirty of the inhabitants, who scattered across the world.

Americas

Aztec

There are several variants of the Aztec story, many of them are questionable in accuracy or authenticity.

- When the Sun Age came, there had passed 400 years. Then came 200 years, then 76. Then all mankind was lost and drowned and turned to fishes. The water and the sky drew near each other. In a single day all was lost, and Four Flower consumed all that there was of our flesh. The very mountains were swallowed up in the flood, and the waters remained, lying tranquil during fifty and two springs. But before the flood began, Titlachahuan had warned the man Nota and his wife Nena, saying, 'Make no more pulque, but hollow a great cypress, into which you shall enter the month Tozoztli. The waters shall near the sky.' They entered, and when Titlacahuan had shut them in he said to the man, 'Thou shalt eat but a single ear of maize, and thy wife but one also'. And when they had each eaten one ear of maize, they prepared to go forth, for the water was tranquil.

- — Ancient Aztec document Codex Chimalpopoca, translated by Abbé Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg.

Note: These Aztec translations are controversial. Many have no credible source and there is no proof of their authenticity. Some are based on the pictograph story of Coxcox, but other translations of this pictograph mention nothing of a flood. Most significantly, the time that these myths were heard from the local people was well after missionaries entered the region.

Inca

In Inca mythology, Viracocha destroyed the giants with a Great Flood, and two people repopulated the earth. Uniquely, they survived in sealed caves.

Chibcha and Muisca

In Colombian mythology, there are references to a great flood that nearly destroyed the whole of mankind and a savior, the god Bochica.

Maya

In Maya mythology, from the Popol Vuh, Part 1, Chapter 3, Huracan ("one-legged") was a wind and storm god who caused the Great Flood (of resin) after the first humans (made of wood) angered the gods (by being unable to worship them). He supposedly lived in the windy mists above the floodwaters and spoke the word "earth" until land came up again from the seas.

Later, in Part 3, Chapter 3&4,

- Four men & four women repopulate the Quiche world after the flood

- all speaking the same language (but a confusing reference)

- and gather together in the same location

- where their speech is changed (affirmed several times)

- after which they disperse throughout the world.

Like many others, this account does not present an "Ark". A "Tower of Babel" depends upon the translation; some render the peoples arriving at a city, others, at a citadel.

Hopi

In Hopi mythology, the people moved away from Sotuknang, the creator, repeatedly. He destroyed the world by fire, and then by cold, and recreated it both times for the people that still followed the laws of creation, who survived by hiding underground. People became corrupt and warlike a third time. As a result, Sotuknang guided the people to Spider Woman, and she cut down giant reeds and sheltered the people in the hollow stems. Sotuknang then caused a great flood, and the people floated atop the water in their reeds. The reeds came to rest on a small piece of land, and the people emerged, with as much food as they started with. The people traveled on in their canoes, guided by their inner wisdom (which is said to come from Sotuknang, through the door at the top of their head). They travelled to the northeast, passing progressively larger islands, until they came to the Fourth World. When they reached the fourth world, the islands sank into the ocean.

Caddo

In Caddo mythology, four monsters grew in size and power until they touched the sky. At that time, a man heard a voice telling him to plant a hollow reed. He did so, and the reed grew very big very quickly. The man entered the reed with his wife and pairs of all good animals. Waters rose, and covered everything but the top of the reed and the heads of the monsters. A turtle then killed the monsters by digging under them and uprooting them. The waters subsided, and winds dried the earth.

Menominee

In Menominee mythology, Manabus, the trickster, "fired by his lust for revenge" shot two underground gods when the gods were at play. When they all dived into the water, a huge flood arose. "The water rose up .... It knew very well where Manabus had gone." He runs, he runs; but the water, coming from Lake Michigan, chases him faster and faster, even as he runs up a mountain and climbs to the top of the lofty pine at its peak. Four times he begs the tree to grow just a little more, and four times it obliges until it can grow no more. But the water keeps climbing "up, up, right to his chin, and there it stopped": there was nothing but water stretching out to the horizon. And then Manabus, helped by diving animals, and especially the bravest of all, the Muskrat, creates the world as we know it today.

Mi'kmaq

In Mi'kmaq mythology, evil and wickedness among men causes them to kill each other. This causes great sorrow to the creator-sun-god, who weeps tears that become rains sufficient to trigger a deluge. The people attempt to survive by traveling in bark canoes, but only a single old man and woman survive to populate the earth.[11]

Polynesian

Several different flood stories are recorded among the Polynesians. None of them approach the scale of the Biblical flood.

The people of Ra'iatea tell of two friends, Te-aho-aroa and Ro'o, who went fishing and accidentally awoke the ocean god Ruahatu with their fish hooks. Angered, he vowed to sink Ra'iatea below the sea. Te-aho-aroa and Ro'o begged for forgiveness, and Ruahatu warned them that they could escape only by bringing their families to the islet of Toamarama. These set sail, and during the night, the island slipped under the ocean, only to rise again the next morning. Nothing survived except for these families, who erected sacred marae (temples) dedicated to the god Ruahatu.

A similar legend is found on Tahiti. No reason for the tragedy is given, but the whole island sunk beneath the sea except for Mount Pitohiti. One human couple managed to flee there with their animals and survived.

In a tradition of the Ngāti Porou, a Māori tribe of the east coast of New Zealand's North Island, Ruatapu became angry when his father Uenuku elevated his younger half-brother Kahutia-te-rangi ahead of him. Ruatapu lured Kahutia-te-rangi and a large number of young men of high birth into his canoe, and took them out to sea where he drowned them. He called on the gods to destroy his enemies and threatened to return as the great waves of early summer. As he struggled for his life, Kahutia-te-rangi recited an incantation invoking the southern humpback whales (paikea in Māori) to carry him ashore. Accordingly, he was renamed Paikea, and was the only survivor (Reedy 1997:83-85).

Some versions of the Māori story of Tawhaki contain episodes where the hero causes a flood to destroy the village of his two jealous brothers-in-law. A comment in Grey's Polynesian Mythology may have given the Māori something they did not have before - as A.W Reed put it, "In Polynesian Mythology Grey said that when Tawhaki's ancestors released the floods of heaven, the earth was overwhelmed and all human beings perished - thus providing the Māori with his own version of the universal flood" (Reed 1963:165, in a footnote). Christian influence has led to the appearance of genealogies where Tawhaki's grandfather Hema is reinterpreted as Shem, son of Noah of the Biblical deluge.

In Hawaii, a human couple, Nu'u and Lili-noe, survived a flood on top of Mauna Kea on the Big Island. Nu'u made sacrifices to the moon, to whom he mistakenly attributed his safety. Kāne, the creator god, descended to earth on a rainbow, explained Nu'u's mistake, and accepted his sacrifice.

In the Marquesas, the great war god Tu was angered by critical remarks made by his sister Hii-hia. His tears tore through heaven's floor to the world below and created a torrent of rain carrying everything in its path. Only six people survived.

Theories of origin

Many[citation needed] orthodox Jews, Muslims and Christians believe that the flood actually happened as recorded in Genesis. The latter say that the large number of flood myths between many cultures suggests that they originated from a common, historical event.[citation needed] Proponents of Flood geology contend that the myths from various cultures are corrupted memories of an historical global deluge.[citation needed] Flood geology is not accepted by geologists, both Christian and non-Christian, who consider it a form of pseudoscience.[12] At one time even prominent workers in Biblical archaeology were willing to argue for a historical worldwide flood,[13][14] but that view is no longer widely held.[15]

There has been speculation that a large tsunami in the Mediterranean Sea caused by the Thera eruption dated ca. 1630-1600 BC geologically, but to ca. 1500 BC archaeologically, was the historical basis for folklore that evolved into the Deucalion myth. One might argue that although the tsunami hit the South Aegean Sea, and Crete, it did not affect cities in the mainland of Greece such as Mycenae, Athens, Thebes which continued to prosper, therefore it had a local rather than a regionwide effect[16].

Other scholars believe that the flood recorded in Genesis is actually a later version of the story, which was based upon earlier Mesopotamian myths (including the Epic of Ziusudra, the Epic of Atrahasis, and the Gilgamesh flood myth)[17]. Although some scholars dispute the idea that the Genesis myth has features that would date it to an even earlier Babylonian version, the various claimed points of uniqueness in the Biblical tale are actually quite common in the earlier versions of the myths as well. According to Biblical scholars Campbell and O'Brien[18] both the J and P portions of the Genesis flood text were authored during and after the Babylonian exile (after 539 BC) and were derived from Babylonian sources. Speaking of the Mesopotamian stories, Georges Roux has stated, "The resemblance with the biblical story, is of course, striking; furthermore it would seem that the Hebrews had borrowed from a long and well established Mesopotamian tradition. The question arose: are there traces of such a cataclysm in Mesopotamia."[19]. This, however, is inconsistent with standards used to treat folklore in other disciplines of study, as later versions of borrowed lore tend to increase in complexity, and the Genesis account is remarkably simple when compared to its "Gilgamesh" counterpart.[citation needed]

Some geologists believe that quite dramatic, greater than normal flooding of rivers in the distant past might have influenced the myths. One of the latest, and quite controversial, theories of this type is the Ryan-Pitman Theory, which argues for a catastrophic deluge about 5600 BC from the Mediterranean Sea into the Black Sea. Many other prehistoric geologic events, including tsunamis, have also been advanced as possible foundations for these myths. For example, some have asserted that the original versions of the Greek myth of Deukalion's flood likely originated from the effects of the megatsunami created by the eruption of Thera in the 18th-15th century BC.[20] More speculatively, some have suggested that flood myths could have arisen from folk stories of the huge rise in sea levels that accompanied the end of the last Ice Age some 10,000 years ago, passed down the generations as an oral history. Another controversial theory is that a deluge was caused by one or more asteroid impacts which released a large amount of water vapor into the atmosphere and low space.

Recently, perhaps starting with the publication of The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor, followed by Fossil Legends of the First Americans, the hypothesis that flood stories have been inspired by ancient observations of fossil seashells and fish inland and on mountains has gained ground. Indeed, there is much documentary evidence to support this view, as the Greeks, Egyptians, Romans, Chinese, and Japanese all commented in ancient writings about seashells and/or impressions of fish that they found inland and/or in the mountains. The Greeks theorized that the earth had been covered by water several times, and noted the seashells and fish fossils that they found on mountain tops as the evidence for this belief. Native Americans also expressed this belief to early Europeans, though they had not written these idea down previously.

Instead of trying to find cataclysmic real life floods to explain these stories, some historians point out that early civilized cultures lived in the fertile flood plains along river basins such as the Nile in Egypt and the Tigris-Euphrates river basin of Mesopotamia (in present day Iraq). The latter is especially prone to violent flash floods, and extensive traces of riverine silt interrupt human settlements at a number of southern Iraqi settlements. It is possible that such peoples would have deep memories of floods and have developed mythologies surrounding floods to explain and cope with an integral part of their lives. To these ancient cultures, a flood that covered their known world, from horizon to horizon, would likely be considered local flooding by First World standards instead of literally the entire planet. Scholars point out that most cultures living in areas where flooding was less likely to occur did not have flood myths of their own. These observations, coupled with the human tendency to make stories more dramatic than events originally warranted, are all the points most mythology scholars feel is necessary to explain how myths of world-destroying, cataclysmatic floods evolved.[citation needed]

Local flood theory

The Sumerian king list describes a very long period of kingship, by which hegemony started with Eridu, the oldest city, and passed to Bad Tabira, Larak, Sippar and then Shuruppak. At the end of the entry on Unar-Tutu, king of Shurrupak the account says briefly "The Flood swept thereover". Kingship when it started again, began with the first Dynasty of Kish. Archaeologists have wondered if there was an actual Mesopotamian flood event in the Early Dynastic Period. A theory that found support with archaeologists Max Mallowan and Leonard Woolley is the local flood theory that links the Ancient Near East flood myths to one specific flood.

Sir Leonard Woolley, in the period from 1929-1934, in his famous excavations of the "Death Pits" at Ur, sank a series of text trenches down to bedrock. Finding early evidence of human habitation, he was surprised to find this sequence interrupted by 11 feet (about 3 1/2 meters) of clean, water-lain silt. Woolley wrote, "Eleven feet of silt would probably mean a flood of no less than 25 feet deep; in the flat low-lying land of Mesopotamia a flood of that depth would cover an area about 300 miles long and 100 miles across....[which is evidence] ...of an inundation unparalleled in any later period of Mesopotamian history"[21]. Woolley concluded that this inundation of the early Ubaid period was the Biblical Deluge, and that the story had been carried to Canaan by Abraham.

However, examining the geology of the Persian Gulf showed that this period coincided with the warm Atlantic phase of world climatic history, when sea levels were 4 meters (12 feet) higher than they are now - the same rise that produced the so-called Black Sea Deluge. This rise of the sea level occurred at the rate of a few centimeters a decade - hardly capable of producing a flash flood described in Biblical or Mesopotamian myth. Furthermore, the Ubaid period dates did not coincide with Jemdet Nasr-Early Dynastic dating as suggested by the Sumerian king list.

Excavations at Shuruppak (modern Fara) conducted by the University of Philadelphia and others, have confirmed that during the end of the Jemdet Nasr period, Shuruppak did boom, as a result of four watercourses converging in the town, making it an important transport hub. The team of archaeologists found a layer of riverine silt, deposited between the late Jemdet Nasr and early Dynastic deposits exactly as indicated by the Sumerian texts. This local river flood of the Euphrates River that has been radio-carbon dated to about 2900 BC at the end of the Jemdet Nasr Period. The Epic of Atrahasis tablet III,iv, lines 6-9 clearly identifies the flood as a local river flood: "Like dragonflies they [dead bodies] have filled the river. Like a raft they have moved in to the edge [of the boat]. Like a raft they have moved in to the riverbank." The WB-444 Sumerian king list places the flood after the reign of Ziusudra, the flood hero in the Epic of Ziusudra that has numerous parallels to the other flood stories. According to archaeologist Max Mallowan[22] the Genesis flood "was based on a real event which may have occurred in about 2900 BC... at the beginning of the Early Dynastic period."

More recently the cause and extent of this flood has been estimated. It has been found that the Shuruppak flood extended as far north as Kish, and was associated with a simultaneous flooding of both the Tigris and the Euphrates. The Priora oscillation was a brief climatic period, about 3,200 BC, which led to a drying of the Middle East and a spread of sand-dunes. One of these dunes dammed the lower course of the Karun River creating an inland lake. In about 2,900 BC, this water swollen by winter rains and melted snows in early summer, broke out towards the north, inundating the Tigris and hence the Euphrates producing the Fara flood mentioned in the Mesopotamian tablets[citation needed].

See also

- Atlantis

- Atrahasis

- Cantref Gwaelod

- Black Sea deluge theory

- Deluge (prehistoric)

- Deucalion

- Epic of Gilgamesh

- Noah

- Not Wanted on the Voyage

- Utnapishtim

- Ys

- 40th century BC

Notes

- ^ Overview of Mesopotamian flood myths

- ^ Jeffrey H. Tigay, The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1982, pages 238-239. ISBN 0-8122-7805-4

- ^ Genesis 6:5–8

- ^ Genesis 6:9–22, 7

- ^ Genesis 8:4,13,14

- ^ Myths and Legends of the Andamanese

- ^ Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines - A Legend of the Great Flood

- ^ Entry Ωγύγιος at Liddell & Scott

- ^ Gaster, Theodor H. Myth, Legend, and Custom in the Old Testament, Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

- ^ Luce, J.V. (1971), "The End of Atlantis: New Light on an Old Legend" (Harper Collins)

- ^ Canada's Fist Nations - Native Creation Myths

- ^ Plimer, Ian (1994) "Telling Lies for God: reason versus creationism" (Random House)

- ^ William F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel (Baltimore: John Hopkins, 1953), 176.

- ^ Nelson Glueck, Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Cudahy, 1959), 31.

- ^ Dever, William G. (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. p. 21. (quoted in Packham, Richard (2006). "Review of Veith: The Genesis Conflict".)

- ^ Castleden, Rodney (2001) "Atlantis Destroyed" (Routledge)

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah, (1963) "The Sumerians: their history, culture and character" (University of Chicago)

- ^ Antony F. Campbell and Mark A. O'Brien, Sources of the Pentateuch, (1993) pp. 2-11, and note 24.

- ^ Roux, Georges (1982) "Ancient Iraq" (Penguin, Harmondsworth)

- ^ http://www.mystae.com/restricted/streams/thera/thera.html

- ^ Woolley, Leonard (1963) "Ur of the Chaldees" (Thames and Hudson)

- ^ M.E.L.Mallowan, "Noah's Flood Reconsidered", Iraq, 26 (1964), pp 62-82.

References

- Alan Dundes (editor), The Flood Myth, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988. ISBN 0-520-05973-5 / 0520059735

- Lloyd R. Bailey. Noah, the Person and the Story, University of South Carolina Press, 1989, ISBN 0-87249-637-6

- Robert M. Best, "Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic", Enlil Press, 1999, ISBN 0-9667840-1-4

- John Greenway (editor), The Primitive Reader, Folkways, 1965

- G. Grey, Polynesian Mythology, Illustrated edition, reprinted 1976. (Whitcombe and Tombs: Christchurch), 1956.

- A.W. Reed, Treasury of Maori Folklore (A.H. & A.W. Reed:Wellington), 1963.

- Anaru Reedy (translator), Ngā Kōrero a Pita Kāpiti: The Teachings of Pita Kāpiti. Canterbury University Press: Christchurch, 1997.

- W. G. Lambert and A. R. Millard, Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood, Eisenbrauns, 1999, ISBN 1-57506-039-6.

External links

- A complete explanation of the flood and the creation Professionl scientists who give a detailed explanation over the flood and more.

- The Great Flood All texts (Eridu Genesis, Atrahasis, Gilgamesh, Bible, Berossus), commentary, and a table with parallels

- Parallels Parallels between versions of the Ancient Near East flood myths.

- Mark Isaak (1996–2002). "Flood stories from around the world". Retrieved 2007-06-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link)- "Mirror from September 2002". Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- "Biblical Evidence for the Universality of the Genesis Flood" by Richard M. Davidson

- The Flood: Myth and Science

- Flood Legends from Around the World

- The Great Atlantis Flood