Turkish people

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 61.2 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| c. 56,400,000[1][2] | |

| 2,700,000[3][4] | |

| 2,500,000[5][6] | |

| 1,500,000[7] | |

| 746,000[8]-[9] | |

| 500,000[10] | |

| 358,000[11] | |

| 300,000[12][13] | |

| 265,000[14][15] | |

| 250,000[16]-[9] | |

| 228,000[17] | |

| 200,000[18][9] | |

| 200,000[19] | |

| 120,000[20] | |

| 100,000[21] | |

| 100,000[22]-[23] | |

| 100,000[24] | |

| 80-120,000[25][26][27] | |

| 78,000[28] | |

| 75,000[29] | |

| 60,000[30] | |

| 24,910[31] | |

| 50,000 (50% of the Muslim minority)[32] | |

| 33,000[33] | |

| 11,000[34] | |

| 10,000[35] | |

| 2,200[citation needed] | |

| 700[36] | |

| 884[37] | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam

| |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Turkish people |

|---|

|

The Turkish people (Turkish: Türk Halkı), also known as "Turks" (Türkler) are a nation (Millet) defined mainly as being speakers of Turkish as a first language.[38]

In the Republic of Turkey, an early history text provided the definition of being a Turk as "any individual within the Republic of Turkey, whatever his faith who speaks Turkish, grows up with Turkish culture and adopts the Turkish ideal is a Turk." This ideal came from the beliefs of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[39]. Today the word is primarily used for the inhabitants of Turkey, but may also refer to the members of sizeable Turkish-speaking populations of the former lands of the Ottoman Empire and large Turkish communities which been established in Europe (particularly in Germany, France, and the Netherlands), as well as North America, and Australia.

History

The word "Turk" was first documented in the 6th century in Central Asia[40][41] The Oghuz Turks were the main Turkic people[42] that moved into Anatolia.[43] Many Turks began their migration after the victory of the Seljuks against the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert on August 26, 1071. The victory, led by Alp Arslan, paved the way for Turkish hegemony in Anatolia.[44][45]

In the centuries after Manzikert local populations began to assimilate to the emerging Turkish population.[46] Over time, as word spread regarding the victory of the Turks in Anatolia, more Turkic ghazis arrived from the Caucasus, Persia, and Central Asia. Turkish migrants began to intermingle with the local inhabitants, which helped to bolster the Turkish-speaking population.

The Ottoman Empire, originally based in the Söğüt region of western Anatolia, was also founded by the Oghuz Turks. Following the Balkan Wars and the Russian conquest of the Caucasus and annexation of Crimea many Turkic speaking Muslims in the North Caucasus, Balkans and Crimea emigrated to the territory of present-day Turkey. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire and formation of the Republic of Turkey these various cultures and languages melded into one supra identity and culture. The modern Turks of Turkey thus are composed of various Turkic groups from various regions.

By the late 19th century Turks were evenly spread throughout Eastern Europe and most noticeably the Balkans; however, territorial losses in the Balkans sparked a large scale exodus from that region. This was finalized by a population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

Göktürk era

Turks are the principal descendants of large bands of nomads who roamed in the Altai Mountains (and thus are also called the Altaic peoples) in northern Mongolia and on the steppes of Central Asia[47]. The original Central Asian Turkic nomads established their first great empire in the 551 AD, a nomadic confederation that they called Göktürks meaning "Sky Turk"[48]. A confederation of tribes under a dynasty of Khans whose influences extended during the sixth to eighth centuries from the Aral Sea to the Hindu Kush in the land bridge known as Transoxania. The Göktürks are known to have been enlisted by a Byzantine emperor in the seventh century as allies against the Sassanians. In the eighth century some Turkish tribes, among them the Oghuz, moved south of the Oxus River, while others migrated west to the northern shore of the Black Sea[49].

Seljuk era

The Seljuks were a Turkic tribe from Central Asia [50]. In 1037, they entered Persia and established their first powerful state, called by historians the Empire of the Great Seljuks. They captured Baghdad in 1055 and a relatively small contingent of warriors (around 5000 by some estimates) moved into eastern Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuks engaged the armies of the Byzantine Empire at Manzikert, north of Lake Van. The Byzantines experienced minor casualties despite the fact that Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes was captured. With no potent Byzantine force to stop them, the Seljuks took control of most of Eastern and Central Anatolia [51]. They established their capital at Konya (ca. 1150) and ruled what would be known as the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. The success of the Seljuk Turks stimulated a response from Latin Europe in the form of the First Crusade. A counteroffensive launched in 1097 by the Byzantines with the aid of the Crusaders dealt the Seljuks a decisive defeat. Konya fell to the Crusaders, and after a few years of campaigning, Byzantine rule was restored in the western third of Anatolia. Although a Turkish revival in the 1140s nullified much of the Christian gains, greater damage was done to Byzantine security by dynastic strife in Constantinople in which the largely French contingents of the Fourth Crusade and their Venetian allies intervened. In 1204, these Crusaders conquered Constantinople and installed Count Baldwin of Flanders in the Byzantine capital as emperor of the so-called Latin Empire of Constantinople, dismembering the old realm into tributary states where West European feudal institutions were transplanted intact. Independent Greek kingdoms were established at Nicaea (present-day Iznik), Trebizond (present-day Trabzon), and Epirus from remnant Byzantine provinces. Turks allied with Greeks in Anatolia against the Latins, and Greeks with Turks against the Mongols. In 1261, Michael Palaeologus of Nicaea drove the Latins from Constantinople and restored the Byzantine Empire. Seljuk Rum survived in the late 13th century as a vassal state of the Mongols, who had already subjugated the Great Seljuk sultanate at Baghdad. Mongol influence in the region had disappeared by the 1330s, leaving behind gazi emirates competing for supremacy. From the chaotic conditions that prevailed throughout the Middle East, however, a new power was to emerge in Anatolia, the Ottoman Turks [52].

Beyliks era

Political unity in Anatolia was disrupted from the time of the collapse of the Anatolia Seljuk State at the beginning of the 14th century (1308), when until the beginning of the 16th century each of the regions in the country fell under the domination of beyliks (principalities). Eventually, the Ottoman principality, which subjugated the other principalities and restored political unity in the larger part of Anatolia, was established in the Eskişehir, Bilecik and Bursa areas [53]. On the other hand, the area in central Anatolia east of the Ankara-Aksaray line as far as the area of Erzurum remained under the administration of the Ilhani General Governor until 1336. The infighting in Ilhan gave the principalities in Anatolia their complete independence. In addition to this, new Turkish principalities were formed in the localities previously under Ilhan occupation.

During the 14th century, the Turkomans, who made up the western Turks, started to re-establish their previous political sovereignty in the Islamic world. Rapid developments in the Turkish language and culture took place during the time of the Anatolian principalities. In this period, the Turkish language began to be used in the sciences and in literature, and became the official language of the principalities. New medreses were established and progress was made in the medical sciences during this period.

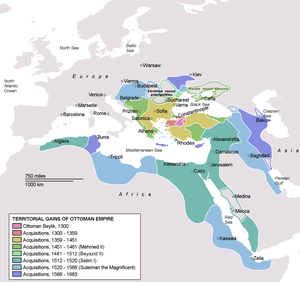

Ottoman era

Starting as a small tribe whose territory bordered on the Byzantine frontier, the Ottoman Turks built an empire that would eventually stretch from Morocco to Iran, from the deserts of Iraq and Arabia to the gates of Vienna.

As the power of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum weakened in the late 1200s, warrior chieftains claimed the lands of Northwestern Anatolia, along the Byzantine Empire's borders. Ertuğrul gazi ruled the lands around Söğüt, a town between Bursa and Eskisehir. Upon his death in 1281, his son, Osman, from whom the Ottoman dynasty and the Empire took its name, expanded the territory to 16,000 square kilometers. Osman I extended the frontiers of Ottoman settlement towards the edge of the Byzantine Empire. He moved the Ottoman capital to Bursa, and shaped the early political development of the nation. Given the nickname "Kara" (Turkish for black) for his courage, [54]

Osman's son, Orhan, conquered Iznik (Nicaea) and took his armies across the Dardanelles and into Thrace and Europe by 1362. By 1452 the Ottomans controlled almost all of the former Byzantine lands except Constantinople. In 1453, Mehmet the Conqueror took the city and made it his capital, extinguishing the 1100-year-old Byzantine Empire forever.

On May 29, 1453, Sultan Mehmed II "the Conqueror" captured Constantinople after a 53-day siege and proclaimed that the city was now the new capital of his Ottoman Empire[55]. Sultan Mehmed's first duty was to rejuvenate the city economically, creating the Grand Bazaar and inviting the fleeing Orthodox and Catholic inhabitants to return. Captured prisoners were freed to settle in the city whilst provincial governors in Rumelia and Anatolia were ordered to send four thousand families to settle in the city, whether Muslim, Christian or Jew, to form a unique cosmopolitan society.

Selim I (r. 1512-20) extended Ottoman sovereignty southward, conquering Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. He also gained recognition as guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina; he accepted pious title of The Servant of The Two Holy Shrines.[56] [57]

Süleyman I (r. 1520-66) is known in the West as Suleiman the Magnificent[58] and in the East, as the Lawgiver (in Turkish Kanuni; Arabic: القانونى, al‐Qānūnī), for his complete reconstruction of the Ottoman legal system. The reign of Süleyman the Magnificent is known as the Ottoman golden age. The brilliance of the Sultan's court and the might of his armies outshone those of England's Henry VIII, France's François I, and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. When Süleyman died in 1566, the Ottoman Empire was a world power. Most of the great cities of Islam--Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Damascus, Cairo, Tunis, and Baghdad were under the sultan's crescent flag. After Süleyman, however, the empire declined rapidly due to poor leadership; many successive Sultans largely depended upon their Grand Viziers to run the empire.

The Ottoman sultanate lasted for over 600 years, but its last three centuries were marked by stagnation and eventual decline. By the 19th century, the Ottomans had fallen well behind the rest of Europe in science, technology, and industry. Reformist Sultans such as Selim III (1789-1807) and Mahmud II (1808-1839) succeeded in pushing Ottoman bureaucracy, society and culture ahead, but were unable to cure all of the empire's ills. Despite its collapse, the Ottoman empire has left an indelible mark on Turkish culture and architecture. Ottoman culture has given the Turkish people a splendid legacy of art, architecture and domestic refinement, as a visit to Istanbul's Topkapi Palace readily shows.

The Republic of Turkey

The Republic of Turkey was born from the disastrous World War I defeat of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman war hero, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later called Atatürk), fled Istanbul to Anatolia in 1919; he organized the remnants of the Ottoman army into an effective fighting force, and rallied the people to the nationalist cause. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander who had distinguished himself during the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish War of Independence was waged with the aim of revoking the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres.[59]. By 1923 the nationalist government had driven out the invading armies, abolished the Ottoman Empire, promulgated a republican constitution, and established Turkey's new capital in Ankara [60].

The new government passed drastic reforms in order to reconstruct Ottoman social structure and politics. Polygamy was abolished, women were granted suffrage and equal legal rights, secularism was institutionalized, the Arabic alphabet was replaced by the Latin alphabet for written Turkish. The Fez and veil were outlawed, and European dress was encouraged.

During a meeting in the early days of the newly proclaimed republic, addressing to the women, Atatürk declaimed:

To the women: 'Win for us the battle of education and you will do yet more for your country than we have been able to do. It is to you that I appeal'.

To the men: 'If henceforward the women do not share in the social life of the nation, we shall never attain to our full development. We shall remain irremediably backward, incapable of treating on equal terms with the civilizations of the West'.[61]— Mustafa Kemal

Chronology of Major Kemalist Reforms:

- 1922 Sultanate abolished (November 1).

- 1923 Treaty of Lausanne secured (July 24). Republic of Turkey with capital at Ankara proclaimed (October 29).

- 1924 Caliphate abolished (March 3). Traditional religious schools closed, seriat abolished. Constitution adopted (April 20).

- 1925 Dervish brotherhoods abolished. Fez outlawed by the Hat Law (November 25). Veiling of women discouraged; Western clothing for men and women encouraged. Western (Gregorian) calendar adopted.

- 1926 New civil, commercial, and penal codes based on European models adopted. New civil code ended Islamic polygamy and divorce by renunciation and introduced civil marriage. Millet system ended.

- 1927 First systematic census.

- 1928 New Turkish alphabet (modified Latin form) adopted. State declared secular (April 10); constitutional provision establishing Islam as official religion deleted.

- 1933 Islamic call to worship and public readings of the Kuran (Quran) required to be in Turkish rather than Arabic.

- 1934 Women given the vote and the right to hold office. Law of Surnames adopted--Mustafa Kemal given the name Kemal Atatürk (Father Turk) by the Grand National Assembly; Ismet Pasha took surname of Inönü.

- 1935 Sunday adopted as legal weekly holiday. State role in managing economy written into the constitution.

Upon the founder's death, his place at the head of the party and the nation was taken by his comrade-in-arms General Ismet Inönü, another hero of the War of Independence. Following Atatürk's advice, Inönü preserved Turkey's precarious neutrality during World War II, figuring that the war could only end in disaster for Turkey.

Geographic distribution

Turks primarily live in Turkey; however, when the borders of the Ottoman Empire became smaller after World War I and the foundation of the new Republic; many Turkish people chose to stay outside Turkey's borders. Since then, some of them have migrated to Turkey but there are still significant minorities of Turks living in different countries such as in Northern Cyprus (Turkish Cypriots), Greece, Bulgaria, Syria, Iraq, Republic of Macedonia, the Dobruja region of Romania and Kosovo (especially in Prizren).

Turks living in other countries can be summarized into three groups; as people who, from Central Asia, have not come to Anatolia, people who have stayed out of the borders after the Republic of Turkey was formed, and people who have gone to other countries as workers. The 20th century has resulted in large groups of Turkish workers in Germany, America and Australia and a new trend of immigration in European countires such as Austria.

Turks in Europe

The post-war migration of Turks to Europe began with ‘guest workers’ who arrived under the terms of a Labour Export Agreement with the Germany in October 1961, followed by a similar agreement with the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria in 1964; France in 1965 and Sweden in 1967. As one Turkish observer noted, ‘it has now been over 40 years and a Turk who went to Europe at the age of 25 has nearly reached the age of 70. His children have reached the age of 45 and their children have reached the age of 20’ [62]. Due to the high rate of Turks in Europe, the Turkish language is now home to one of the largest group of pupils after the German-speakers. Turkish in Germany is often used not only by members of its own community but also by people with a non-Turkish background. Especially in urban areas, it functions as a peer group vernacular for children and adolescents [63]. The increasing Turkish population of Europe can be explained by the continuation of migration through marriages and by the high birth rate of the Turkish population. This high rate has as a consequence that Turkish migrant population is very young (1/3 is under 18 years old); more than 80% of these young people have been born and schooled in Europe.

Turks in North America

In the United States, the largest Turkish communities are found in Paterson, New York City, Chicago, Miami, and Los Angeles. Since the 1970s, the number of Turkish immigrants has risen to more than 2,000 per year. There is also a growing Turkish population in Canada, Turkish immigrants have settled mainly in Montreal and Toronto, although there are small Turkish communities in Calgary, Edmonton, London, Ottawa, and Vancouver. The population of Turkish Canadians in Metropolitan Toronto may be as large as 5,000.

Culture

The culture of Turkish people is a diverse one, derived from various elements of the Ottoman Empire, European, and the Islamic traditions. Turkish culture is an immense mixture partly produced by the rich history. The original lands of Turks is Central Asia, bordering China. From this location, they were forced to move west for various reasons more than a thousand years ago. On the way to Anatolia they have interacted with Chinese, Indian, Middle Eastern, European and Anatolian civilizations, and today's Turkish culture carries motives from each one of these diverse cultures.

Because of the different historical factors playing an important role in defining a Turkish identity, the culture of Turkey is an interesting combination of clear efforts to be "modern" and Western, alongside a desire to maintain traditional religious and historical values.

Language

The Turkish language is a member of the ancient Oghuz subdivision of Turkic languages, which in turn is a branch of the proposed Altaic language family.[64][65][66] Turkish is for the most part, mutually intelligible with other Oghuz languages like Azeri, Crimean Tatar, Gagauz, Turkmen and Urum, and to a lesser extent with other Turkic languages.

Modern Turkish differs greatly from the Ottoman Turkish language, the administrative and literary language of the Ottoman Empire was influenced by Arabic and Persian. During the Ottoman period, the language was essentially a mixture of Turkish, Persian, and Arabic, differing considerably from the everyday language spoken by the empire's Turkish subjects, to the point that they had to hire arzıhâlcis (request-writers) to communicate with the state. After the proclamation of the Turkish Republic in early 20th century, many of the foreign borrowings in the language were replaced with Turkic equivalents in a language reform by the newly founded Turkish Language Association. Almost all government documents and literature from the Ottoman period and the early years of the Republic are thus unintelligible to today's Turkish-speaker without translation.

Historically, there were many dialects of Turkish that were spoken throughout Anatolia and the Balkans that differed significantly from each other. After the proclamation of the Republic, the Istanbul dialect was adopted as the standard. There is no official effort to protect regional dialects, and some are currently under threat of disappearing as they face the standard language used in the media and educational system.

Turkish heritage

Some 180 million people have a Turkic language as their native language; an additional 20 million people speak a Turkic language as a second language. The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish proper, or Anatolian Turkish, the speakers of which account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers, dwelling predominantly in Turkey proper and formerly Ottoman-dominated areas of Eastern Europe and West Asia; as well as in Western Europe, Australia and the Americas as a result of immigration. The remainder of the Turkic peoples are concentrated in Central Asia, Russia, the Caucasus, China, and northern and northwestern Iran.

Arts and Calligraphy

A transition from Islamic artistic traditions under the Ottoman Empire to a more secular , Western orientation has taken place in Turkey. Turkish painters today are striving to find their own art forms, free from Western influence. Sculpture is less developed, and public monuments are usually heroic representations of Ataturk and events from the war of independence. Literature is considered the most advanced of contemporary Turkish arts. The reign of the early Ottoman Turks in the (16th and early 17th centuries) introduced the Turkish form of Islamic calligraphy. It was invented by Housam Roumi and reached its height of popularity under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–66). As decorative as it was communicative, Diwani was distinguished by the complexity of the line within the letter and the close juxtaposition of the letters within the word.

Architecture

|

|

Turkish architecture reached its peak during the Ottoman period. Ottoman architecture, influenced by Seljuk, Byzantine and Islamic architecture, came to develop a style all of its own.

The years 1300-1453 constitute the early or first Ottoman period, when Ottoman art was in search of new ideas. During this period we encounter three types of mosque: tiered single-domed and sub line-angled mosques. The Junior Haci Özbek Mosque (1333) in Iznik, the first important centre of Ottoman art, is the first example of Ottoman single-domed mosques.

The architectural style which was to take on classical form after the conquest of Istanbul, was born in Bursa and in Edirne. The Great Mosque (Ulu Cami) in Bursa was the first Seljuk mosque to be converted into a domed one. Edirne was the last Ottoman capital before Istanbul, and it is here that we witness the final stages in the architectural development that culminated in the construction of the great mosques of Istanbul. The buildings constructed in Istanbul between the capture of the city and the construction of the mosque of Sultan Bayezit are also considered works of the early period. Among these are the mosques of Fatih (1470), the mosque of Mahmutpasa, Tiled Pavilion and Topkapi Palace.

In Ottoman times the mosque did not exist by itself. It was looked on by society as being very much interconnected with city planning and communal life. Beside the mosque there were soup kitchens, theological schools, hospitals, Turkish baths and tombs.

Examples of Ottoman architecture of the classical period, aside from Istanbul and Edirne, can also be seen in Egypt, Tunisia, Algiers, the Balkans and Hungary, where mosques, bridges, fountains and schools were built.

During the years 1720-1890, Ottoman art deviated from the principles of classical times. In the 18th century, during the Lale (Tulip) period, Ottoman art came under the influence of the excessive decorations of the west; Baroque, Rococo, Ampir and other styles intermingled with Ottoman art. Fountains became the characteristic structures of this period. An eclecticism set in. The Aksaray Valide mosque in Istanbul is an example of the mixture of Turkish art and Gothic style.

Music

The roots of traditional music in Turkey spans across centuries to a time when the Seljuk Turks colonized Anatolia and Persia in the 11th century and contains elements of both Turkic and pre-Turkic influences. Much of its modern popular music can trace its roots to the emergence in the early 1930s drive for Westernization [67].

Traditional music in Turkey falls into two main genres; classical art music and folk music. Turkish classical music is characterized by an Ottoman elite culture and influenced lyrically by neighbouring regions and Ottoman provinces [68] Earlier forms are sometimes termed as saray music in Turkish, meaning royal court music, indicating the source of the genre comes from Ottoman royalty as patronage and composer.[69] Neo-classical or postmodern versions of this traditional genre are termed as art music or sanat musikisi, though often it is unofficially termed as alla turca. In addition, from the saray or royal courts came the Ottoman military band, Mehter takımı in Turkish, considered to be the oldest type of military marching band in the world. It was also the forefather of modern Western percussion bands and has been described as the father of Western military music [70].

Turkish folk music is the music of Turkish-speaking rural communities of Anatolia, the Balkans, and Middle East. While Turkish folk music contains definitive traces of the Central Asian Turkic cultures, it has also strongly influenced and been influenced by many other indigenous cultures. Religious music in Turkey is sometimes grouped with folk music due to the tradition of the wandering minstrel or aşık (pronounced ashuk), but its influences on Sufism due to the spritiual Mevlevi sect arguably grants it special status.[71] It has been suggested the distinction between the two major genres comes during the Tanzîmat period of Ottoman era, when Turkish classical music was the music played in the Ottoman palaces and folk music was played in the villages.[72]

Musical relations between the Turks and the rest of Europe can be traced back many centuries,[73] and the first type of musical Orientalism was the Turkish Style.[74] European classical composers in the 18th century were fascinated by Turkish music, particularly the strong role given to the brass and percussion instruments in Janissary bands. Joseph Haydn wrote his Military Symphony to include Turkish instruments, as well as some of his operas. Turkish instruments were also included in Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony Number 9. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote the "Ronda alla turca" in his Sonata in A major and also used Turkish themes in his operas, such as the Chorus of Janissaries from his Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782). This Turkish influence introduced the cymbals, bass drum, and bells into the symphony orchestra, where they remain. Jazz musician Dave Brubeck wrote his "Blue Rondo á la Turk" as a tribute to Mozart and Turkish music.

Today Turkish pop music boasts numerous mainstream artists with large followings since the 1960s like Ajda Pekkan and Sezen Aksu, and younger pop stars like Sertab Erener, Tarkan, Serdar Ortac and Mustafa Sandal. Underground music and the genres of electronica, hip-hop, rap and dance music saw an increased demand and activity following the 1990s. Turkish rock music, sometimes referred to as Anatolian rock, initiated during the 1960s by individuals like Cem Karaca, Barış Manço, and Erkin Koray, has seen wide-range success and has grown a considerable fan base.

Literature

The history of Turkish literature may be divided into three periods, reflecting the history of Turkish civilization as follows; the period up to the adoption of Islam, the Islamic period, and the period under western influence[75]. Before the adoption of Islam, the Seljuks had a mainly oral tradition.

The oldest known examples of Turkish writings are on obelisks dating from the late 7th and early 8th centuries. The Orhun monumental inscriptions written in 720 for Tonyukuk, in 732 for Kültigin and in 735 for Bilge Khan are masterpieces of Turkish literature with their subject matter and ideal style. Turkish epics dating from those times include the Yaratilis, Saka, Oguz-Kagan, Göktürk, Uygur and Manas. The "Book of Dede Korkut", put down in writing in the 9th century, is an extremely valuable work that preserves the memory of that epic era in Turkish literature [76].

Following Turkish migrations into Anatolia in the wake of the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the establishment of various Beyliks in Anatolia and the eventual founding of the Seljuk and Ottoman Empires set the scene for Turkish literature to develop along two distinct lines, with "divan" or classical literature drawing its inspiration from the Arabic and Persian languages and Turkish folk literature still remaining deeply rooted in Central Asian traditions.

In 1928, five years after the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey, the Arabic alphabet was replaced by the Latin one, which in turn speeded up the movement to rid the language of foreign words. The Turkish Language Institute was established in 1932 to carry out linguistic research and contribute to the natural development of the language. As a consequence of these efforts, modern Turkish is a literary and cultural language developing naturally and free of foreign influences.

To a certain extent, theTurkish folk literature which has survived till our day, reflects the influence of Islam and the new life style and form of the traditional literature of Central Asia after the adoption of Islam. Turkish folk literature comprised anonymous works of bard poems and Tekke (mystical religious retreats) literature. Yunus Emre who lived in the second half of the 13th and early 14th centuries was an epoch making poet and sufi (mystical philosopher) expert in all three areas of folk literature as well as divan poetry. Important figures of poetic literature were Karacaoglan, Atik Ömer, Erzurumlu Emrah and Kayserili Seyrani.

Turkish Literature was also influenced by the Western world throguh social, economic and political changes which were reflected in the literature of the time. Leading figures in the first period (1860-1880) in Tanzimat literature were Sinasi, Ziya Pasa, Namik Kemal, and Ahmet Mithat Efendi. Leading figures during the second period (1880-1896) were Mahmut Ekrem, Abdülhak Hamit, Sami Pasazade Sezai, and Nabizade Nazim. Tevfik Fikret, Süleyman Nazif, and Halit Ziya Usakligil are the important representatives of this trend. Others who adopted the western approach, but who were outside the group, were Ahmet Rasim and Hüseyin Rahmi Gürpinar who supported the new Turkish literature.

The backgrounds of current novelists can be traced back to "Young Pens" (Genç Kalemler) journal in Ottoman period. Young Pens was published in Selanik under the Ömer Seyfettin, Ziya Gökalp ve Ali Canip Yontem. They covered the social and political concepts of their time with the nationalistic perspective. They became the core of a movement which will be called national literature.

With the declaration of republic, Turkish literature becomes interested in folkloric styles. This was also the first time the literature was escaping from the western influence and begin to mix western forms with others. During the 1930s Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu and Vedat Nedim Tor begin to publish Kadro, a leftist revolutionary journal. Kemal Tahir was a prominent modern Turkish novelist. Among authors translated into English is Yaşar Kemal.

Orhan Pamuk is a Turkish novelist of post-modern literature. He is hugely popular in his homeland, but also with a growing readership around the globe. As one of Europe's most prominent novelists, his work has been translated into more than twenty languages. He is the recipient of major Turkish and international literary awards. His most recent novel is "Snow". Pamuk won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006, with his melancholic point of view to various cultures in Istanbul. However, a big debate is going on in Turkey about Pamuk winning; many Turks think that he won the prize because of his political ideas.

Religion

The Turks first came in contact with the traditions of the Islamic world at the beginning of the 8th century and fully embraced Islam in the 10th century,[77] establishing the Kara-Khanid Khanate (990–1212) in Central Asia as the first Muslim Turkic state.[78]

The vast majority of the present-day Turkish people are Muslim and the most popular sect is the Hanafite school of Sunni Islam, which was officially espoused by the Ottoman Empire; according to a Eurobarometer Poll 2005:[79]

- 95% of Turkish citizens responded that "they believe there is a God".

- 2% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force".

- 1% answered that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".

Secularism in Turkey was introduced with the Turkish Constitution of 1924, and later the Atatürk's Reforms set the administrative and political requirements to create a modern, democratic, secular state aligned with the Kemalist ideology. Thirteen years after its introduction, laïcité (February 5 1937) was explicitly stated as a property of the State in the second article of the Turkish constitution. The current Turkish constitution neither recognizes an official religion nor promotes any. This includes Islam, which at least nominally more than 95% of citizens subscribe to [80].

In addition to Islam, smaller groups adhere to Alevi, Christianity and Judaism.

Sciences and technology

From the sixteenth century onwards, noteworthy geographical works were produced by Piri Reis, In 1511, Pîrî Reis drew his first map. This map is part of the world map prepared on a large scale. It was drawn on the basis of his rich and detailed drafts an in addition, European maps including Columbus' map of America. This first Ottoman map which included preliminary information about the New World represents south western Europe, north western Africa, south eastern and Central America. It is a portalano, without latitude and longitude lines but with lines delineating coasts and islands. Pîrî Reis drew his second map and presented it to Süleyman the Magnificent in 1528. Only the part which contains the North Atlantic Ocean and the then newly discovered areas of Northern and Central America is extant.

Symbols

The most widely used symbol by Turkish people is the crescent moon and a star. The Turkish flag is also widely used by the Turkish Cypriot community in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

-

The late Ottoman Navy flag

-

Ottoman Naval Flag, flying on all military vessels 1793-1844

-

Ottoman Religious Flag, or the Flag of the Caliphate 1793-1844

-

The last flag of the Ottoman Empire from 1844 to 1923 was adopted with the Tanzimat reforms as the first official Ottoman national flag

-

Flag of The Republic of Turkey

Turkish Timeline

Throughout history the Turks have established numerous states in different geographical areas on the continents of Asia, Europe and Africa. Therefore, they encountered different cultures, influenced these cultures and have also been influenced by them. This list consists of the main events of the ancient Turks to today's modern Turks.

| Time | Events |

|---|---|

| c.200 BCE-216 | Hun Empire/ Confederations in Central Asia |

| c.350-550 | Hun Empire in Eastern Europe and Western Asia |

| 434-453 | Rule of Attila |

| c.552-744 | Gokturk Empire/ Confederation in Central Asia |

| 732-735 | Orkhon Inscriptions, first discovered records in Turkish |

| c.620-1016 | Khazar Kingdom in Western Central Asia, (today's southern Russia and Eastern Ukraine) |

| 9th Century | Oguz Confederation of tribes north of the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) and in Transoxania |

| 830-850 | Turkish mercenaries from Central Asia found in service of Abbasid caliphs |

| 850-905 | Tulunids (Turkish generals) rule Egypt virtually independently of the Abbasids |

| 900 | Samanids rule in eastern Persia and borderlands of Turkistan; Turks are exposed to Persianate Islamic culture; preparation far incorporation of Turks into main body of Middle Eastern Islamic civilization |

| 10thc. | Term ‘sultan’ (Arabic abstract noun meaning ”sovereign authority”) begins to be used to designate rulers |

| c.1000 | Ghaznavids establish rule in Afghanistan, break Samanid power, and expand into Persia below Oxus River; champions of Sunni Islam within a predominantly Persian cultural context |

| 1040 | Seljuks take Khorasan from Ghaznavids; soon control most of Persia with center at Isfahan; from there advance to defeat Buwayhids (Shi’i Persians) who had dominated Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad for a century |

| 1055 | Seljuk sultans become de facto rulers in Abbasid Baghdad; two centuries of turmoil is ended and unity restored in eastern Islamic region; Persia and Mesopotamia are reunited and northern Syria added to the ”Great Seljuk” state |

| 1071 | Battle of Manzikert ( Malazgirt ) a decisive victory for Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan over Byzantines; break Byzantine line of defense in Eastern Anatolia; Turkish-speaking Muslims raid and settle in area now known as ”Turkey”; much of the Greek/ Christian veneer of indigenous Anatolian population gradually replaced by a Turkish/Muslim veneer |

| 1092 | Death of Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah and his great vizier, Nizam al-Mulk; dynastic strife ensues |

| 1118 | Seljuk Empire splits into principalities ruled by princes of the family, often over- shadowed by their ”atabeys” ( tutor guardians ) |

| 12th century | Seljuks of Rum (Konya, Anatolia) rule centra1 Anatolian plateau with center at Konya (Iconium). |

| 1204 | Byzantium fatally weakened by 4th. Crusade and Latin occupation |

| c.1200 | high point of Seljuk’s of Rum; by absorption of smaller Turkish principalities (Beyliks), Seljuk’s extend their jurisdiction to south coast of Anatolia; Turkish nomads (‘Gazis’) active in western border/march region adjacent to Byzantium |

| 1243 | Mongols under Hulagu Khan’s move west, defeat Seljuk Sultan Kaykhusrav II, and establish over lordship in Seljuk Anatolia |

| class="col-break " |

| Time | Events |

|---|---|

| 1258 | Mongols conquer Baghdad and bring Abbasid Caliphate to an end |

| 13th c. | Turkish Anatolia fragmented as Mongol control weakens and is withdrawn; many small principalities ( Beyliks ) emerge, one of them led by Osman (Turkish form of the Arabic/Muslim name, Uthmm; European corruption of Osman is Ottoman) in northwest Anatolia (around Iznik and Bursa) adjacent to Byzantine territories. |

| 1071-1300 | Anatolia witnesses swift military penetration, ragged political conquest, partial and superficial cultural/linguistic conquest by Muslim Turks who, in their upper ranks were carriers of Persianate Muslim culture. That group was small in number but powerful. Below them, Turkish-speaking Muslims mix with indigenous population. Folk culture and folk religion often at odds with high culture and Islamic orthodoxy represented by the religious and political elite in the society. |

| 1288 | Foundation of the Ottoman state by a warrier chieftain named Osman, at Sögüt near Bursa. |

| 1453 | Conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul) by Sultan Mehmet II 'the Conqueror'. |

| 1520-1566 | Reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, the great age of the Ottoman Empire. The sultan rules most of North Africa, most of Eastern Europe and all of the Middle East. His navies patrol the Mediterranean and Red seas and the Indian Ocean. |

| 1699 | Treaty of Karlowitz, the first time in over 400 years that the Ottomans were decisively defeated and forced to sign a peace treaty as the clear losers. The mighty empire was clearly in decline. |

| 1876-1909 | Reign of Abdülhamid II, a ruthless despot who was the last of the powerful sultans. |

| 1914-1918 | The Ottoman Empire enters World War I in alliance with Germany. Australian, British, French and New Zealand troops invade Gallipoli which is successfully defended by Ottoman forces led by Mustafa Kemal. Eventual defeat of the Ottomans, loss of most of the empire's territory, and occupation of parts of Anatolia by victorious foreign troops. |

| 1919-1923 | Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) organizes remaining Ottoman military units into an army of resistance, and establishes a government of resistance at Ankara. |

| 1922 | Encouraged by Great Britain, Greece invades Anatolia through Izmir and presses eastward, threatening the fledgling government in Ankara. |

| 1923 | Defeat and expulsion of the invading armies. Abolishment of the last vestiges of the Ottoman Empire and Proclamation of the Turkish Republic by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, its founder and first president. Most ethnic Greeks in Turkey, and ethnic Turks in Greece, migrate to the opposite country. |

| 1923-1938 | Atatürk's reforms: equal rights for women, secular government, prohibition of the fez and the veil, substitution of the Latin alphabet for the Arabic, Turkification of city names, everyone adopts a surname, etc. |

| 1938 | Death of Atatürk, continuation of one-party rule. |

| 1939-1945 | Turkey maintains a precarious neutrality during World War II. |

| 1946-1950 | Institution of multi-party democracy. |

Possible genetic links

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (April 2008) |

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (March 2008) |

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (March 2008) |

Turkey is situated on the bridgehead between Europe and Asia. The data on the DNA of Turkish people suggests that a human demographic expansion occurred sequentially in the Middle East, through Anatolia, and finally to the rest of Europe. The estimated time of this expansion is roughly 50,000 years ago, which corresponds to the arrival of anatomically modern humans in Europe.[81] During antiquity Anatolia was a cradle for a wide variety of numerous indigenous peoples as Armenians, Assyrians, Hattians, Hittites, Hellenes, Pelasgians, Phrygians, Thracians, Medes and others. It is concluded that aboriginal Anatolian groups (older than 2000 BCE) may have given rise to present-day Turkish population.[82] DNA results suggests the lack of strong genetic relationship between the Mongols and the Turks despite the close relationship of their languages and shared historical neighborhood.[83] Anatolians do not significantly differ from other Mediterraneans, indicating that while the ancient Asian Turks carried out an invasion with cultural significance (language), it is not genetically detectable.[84] Recent genetic research has suggested the local, Anatolian origins of the Turks and that genetic flow between Turks and Asiatic peoples might have been marginal.[85]

According to a 1998 study:

Whereas the historical and cultural consequences of the Turkic invasion of Anatolia were profound, the genetic contribution of he Turkic people to the modern Turkish population seems less significant. Previous studies ... have shown that the mtDNA pool found in Turkey can be interpreted as the result of upper Paleolithic and/or Neolithic expansions from the Middle East to Europe, with a small contribution by Asian sequences. The present results show that those sequences were found in the Turkic central Asian peoples, whose ancestors may have brought the Asian mtDNA sequences to Anatolia. [86]

The major components, 94.1% (haplogroups E3b, G, J, I, L, N, K2, and R1), are shared with European and Near Eastern populations. In contrast, only a minor share of haplogroups are attributed to Central Asian (C, Q and O; 3.4%), Indian (H, R2; 1.5%), and African (A, E3*, E3a; 1%) affinity.[87] The comprehensive high resolution SNP analysis of 513 individuals provides slight paternal gene flow (<9%) from Central Asia. Various estimates exist of the proportion of gene flow associated with the arrival of Central Asian Turkic speaking people to Anatolia. One study based on an analysis of Y-chromosomes from Turkey suggested that Central Asians have only made a 10% genetic contribution (Rolf et al. 1999). Another study suggests roughly 30% based upon mtDNA control region sequences and one STR Y-chromosome (Di Benedetto et al.[88] 2001). While it is likely that genetic flow from Central Asia to Anatolia has occurred repeatedly throughout prehistory, uncertainties exist with respect to the source populations and the number of such episodes between Central Asia and Europe. These uncertainties confound any assessment of the genetic contribution of the 11th century AD Oghuz nomads responsible for the Turkic language replacement. The recent Y-chromosome data provides candidate haplogroups to differentiate lineages specific to the postulated source populations, thus overcoming potential artifacts caused by indistinguishable overlapping gene flows.

Using Central Asian Y-chromosome data from either 13 populations and 149 samples (Underhill et al. 2000) or 49 populations and 1,935 samples (Wells et al. 2001) where these diagnostic lineages occur at 33% and 18%, respectively, their estimated contribution is 8.5%. During the Bronze Age, the population of Anatolia expanded and reached an estimated level of 12 million people during the late Roman Period (Russell 1958). Such a large preexistent Anatolian population would have reduced the impact of the subsequent arrival of the Turkic-speaking Seljuk and Osmanlı groups from Central Asia. Although the genetic research of Anatolia still remains somewhat inchoate, the excavations of these new levels of shared Y-chromosome heritage and subsequent diversification provide new clues to Anatolian prehistory, as well as a substantial foundation for comparisons with other populations. The results demonstrate Anatolia’s role as a buffer between culturally and genetically distinct populations, being both an important source and recipient of gene flow.(see the plot:). According to Spencer Wells:[89]

The Turkish and Azeri populations are atypical among Altaic speakers in having low frequencies of M130, M48, M45, and M17 haplotypes. Rather, these two Turkic-speaking groups seem to be closer to populations from the Middle East and Caucasus, characterized by high frequencies of M96- and/or M89-related haplotypes. This finding is consistent with a model in which the Turkic languages, originating in the Altai-Sayan region of Central Asia and northwestern Mongolia, were imposed on the Caucasian and Anatolian peoples with relatively little genetic admixture---another possible example of elite dominance-driven linguistic replacement.

A 2007 study suggests that, genetically Anatolians are more closely related with the Balkan populations than to the Central Asian populations. Central Asian contribution to Anatolia with respect to the Balkans was quantified with an admixture analysis. Furthermore, the association between the Central Asian contribution and the language replacement episode was examined by comparative analysis of the Central Asian contribution to Anatolia, Azerbaijan (another Turkic speaking country) and their neighbors. In this study, the Central Asian contribution to Anatolia was estimated as 13%. This was the lowest value among the populations analyzed. This observation may be explained by Anatolia having the lowest migrant/resident ratio at the time of migrations.[90]

The question to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia to Anatolia has contributed to the current gene pool of the Turkish people, and what the role is in this of the 11th century invasion by Oghuz Turks, has been the subject of several studies. A factor that makes it difficult to give reliable estimates, is the problem of distinguishing between the effects of different migratory episodes. Per Chinese records, Kyrgyz Turks were the last Turks left ancient Mongolia due to massive Mongol settlement from east 600 A.D. Kyrgyz Turks possessed lighter hair color (including reddish), lighter eye colors and they were taller in height and strong people. Recent genetics research dated 2003[91] confirms the studies[92] indicating that the Turkic peoples[93] originated from Central Asia and therefore are possibly related with Xiongnu. According to the study, Turkish Anatolian tribes may have some ancestors who originated in an area north of Mongolia at the end of the Xiongnu period (3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE), since modern Anatolian Turks appear to have some common genetic markers with the remains found at the Xiongnu period graves in Mongolia:

The researchers found that interbreeding between Europeans and Asians occurred much earlier than previously thought. They also found DNA sequences similar to those in present-day Turks, supporting the idea that most of the Turks originated in Central Asia. Interestingly, this paternal lineage has been, at least in part (6 of 7 STRs), found in a present-day Turkish individual (Henke et al. 2001). Moreover, the mtDNA (female linkeage) sequence shared by four of these paternal relatives (from graves 46, 52, 54, and 57) were also found in a Turkish individuals (Comas et al. 1996), suggesting a possible Turkish origin of these ancient specimens. Two other individuals buried in the B sector (graves 61 and 90) were characterized by mtDNA sequences found in Turkish people (Calafell 1996; Richards et al. 2000).[94][95]

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

References and notes

- ^ The World Factbook - Turkey

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Turkey: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995. Turks

- ^ "Turkish Migrants in Germany, Prospects of Integration", Observatory of European Foreign Policy

- ^ C. Zouboulis, Christos (2003). Behçet's disease in Patients of German and Turkish Origin. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 0306477572.

- ^ Religion by Location: Iraq

- ^ "'The fifth most spoken language of the world' Turkish" (PDF) (Press release). Mirora Translation & Consultancy Co.

- ^ Aksiyon - Syrian Turks

- ^ National Statistical Institute - Population by districts and ethnos as of 1-03-2001 (census figures)

- ^ a b c Gulcan, Nilgun (2006-04-16). "Population of Turkish Diaspora".

- ^ Hunter, Shireen (2002). Islam, Europe's Second Religion: The New Social, Cultural, and Political Landscape. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 6. ISBN 978-0275976088.

- ^ Euro Islam: The Netherlands

- ^ Muslim Laws, Politics and Society in Modern Nation States

- ^ "'Turkish London'" (PDF) (Press release). Visit London.

- ^ Template:PDFlink Nüfus ve Konut Sayimi

- ^ ATCA news:National census held on 01/05/06 records a population of 264,172

- ^ Großer Türkenanteil in Österreich

- ^ Ethnologue report for Uzbekistan

- ^ "'Belgian-Turks A Bridge or a Breach between Turkey and the European Union?'" (PDF) (Press release). King Baudouin Foundation.

- ^ US demographic census

- ^ Gerald Robbins. Fostering an Islamic Reformation. American Outlook, Spring 2002 issue.

- ^ 1999 Azerbaijani census

- ^ Statistik Schweiz - Wohnbevölkerung nach Nationalität (2000)

- ^ 2002 Macedonian census

- ^ 2002 Russian census - Nationality report

- ^ DESTROYING ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE TURKS OF GREECE

- ^ The Human Rights Watch: Turks Of Western Thrace

- ^ Greek - Turkish minorities

- ^ Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002

- ^ 2002 census in Serbia (excluding Kosovo)

- ^ Immigrant Turks and their socio-economic structure in European countries

- ^ Turkish Canadian Relations

- ^ Greek MFA Census Data on Thrace Minorities

- ^ Census 2002

- ^ Statistiche demografiche ISTAT

- ^ "Japonya Türk Toplumu (Turkish Community of Japan)" (in Turkish). Embassy of Turkey in Japan. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ Demographics of Tajikistan

- ^ Liechtenstein - Turkey

- ^ Turks, The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-07.

- ^ van Schendel, Willem (2001). Identity Politics in Central Asia and the Muslim World. I.B. Tauris.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Central Asia (The Middle Ages) History of the Turks Article

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05. Turks.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Oguz Article

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Seljuq Article

- ^ Medieval Sourcebook, Anna Comnena, The Alexiad: Complete Text

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Seljuq Article

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Battle of Manzikert Article

- ^ Deny (2000). History of the Turkic Peoples in the Pre-Islamic Period. Schwarz. pp. page 108.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Seljuk Turks Period (1071-1243 AD)

- ^ Turkish origins

- ^ Concise Britannica Online Seljuq Dynasty article

- ^ The History of the Seljuq Turks: From the Jami Al-Tawarikh (LINK)

- ^ Gürpınar, Doğan (2004). "THE SELJUKS OF RUM IN TURKISH REPUBLICAN NATIONALIST HISTORIOGRAPH" (PDF). Sabancı University. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fleet, Kate (1999). "European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Template:Tr Sultan Osman I, Turkish Ministry of Culture website

- ^ D. Nicolle, Constantinople 1453: The end of Byzantium, 32

- ^ Yavuz Sultan Selim Government Retrieved on 2007-09-16

- ^ The Classical Age, 1453-1600 Retrieved on 2007-09-16

- ^ Merriman.

- ^ Mango, Andrew (2000). Ataturk. Overlook. ISBN 1-5856-7011-1.

- ^ Ahmad, The Making of Modern Turkey, 50

- ^ Kinross, Ataturk, The Rebirth of a Nation, p. 343

- ^ Gogolin, Ingrid (2005). "Turks in Europe: Why are we afraid?" (PDF). The Foreign Policy Centre. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Twigg, Stephen (2002). "LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY AND NEW MINORITIES IN EUROPE" (PDF). Language Policy Division. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Georg, S., Michalove, P.A., Manaster Ramer, A., Sidwell, P.J.: "Telling general linguists about Altaic", Journal of Linguistics 35 (1999): 65-98 Online abstract and link to free pdf

- ^ Altaic Family Tree

- ^ Linguistic Lineage for Turkish

- ^ Stokes, Martin (2000). Sounds of Anatolia. Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0., pp 396-410.

- ^ "Traditional Music in Turkey". Medieval.org.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help). The Ottoman Empire included substantial territory which had been under Byzantine or Arabic control, and the substratum of traditional music in Turkey was conditioned by that history. - ^ "Suleyman the Magnificent". HyperHistory Biographies. Retrieved April 3.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) During his rule as sultan, the Ottoman Empire reached its peak in power and prosperity. Suleyman filled his palace with music and poetry and came to write many compositions of his own. - ^ "Ottoman Military Music". MilitaryMusic.com. Retrieved February 11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Introduction to Sufi Music and Ritual in Turkey". Middle East Studies Association of North America.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) The tradition of regional variations in the character of folk music prevails all around Anatolia and Thrace even today. The troubadour or minstrel (singer-poets) known as aşık contributed anonymously to this genre for ages. - ^ "The Ottoman Music". Tanrıkorur, Cinuçen (Abridged and translated by Dr. Savaş Ş. Barkçin). Retrieved June 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Levantine life: Giuseppe Donizetti at the Ottoman court". Araci, Emre. The Musical Times. Retrieved October 3.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Famous opera composer Gaetano Donizetti's brother, Giuseppe Donizetti, was invited to become Master of Music to Sultan Mahmud II in 1827. - ^ Bellman, Jonathan (1993). The Style Hongrois in the Music of Western Europe. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-169-5. pp.13-14; see also pp.31-2. According to Jonathan Bellman, it was "evolved from a sort of battle music played by Turkish military bands outside the walls of Vienna during the siege of that city in 1683."

- ^ Turkish Literature

- ^ Turkish Odyssey: Book of Dede Korkut

- ^ The History of Turkey

- ^ Sabanci University: Turkish History

- ^ "Eurobarometer on Social Values, Science and technology 2005 - page 11" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ Çarkoǧlu, Ali (2004). Religion and Politics in Turkey. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-4153-4831-5.

- ^ Calafell, F; Underhill P, P; Tolun, A; Angelicheva, D; Kalaydjieva L., L. (2006-01). "From Asia to Europe: mitochondrial DNA sequence variability in Bulgarians and Turks". Annals of Human Genetics. 60 (1): 35–49. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1996.tb01170.x.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ (2001) HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans Tissue Antigens 57 (4), 308–317

- ^ Tissue Antigens. Volume 61 Issue 4 Page 292-299, April 2003. Genetic affinities among Mongol ethnic groups and their relationship to Turks

- ^ Tissue Antigens Volume 60 Issue 2 Page 111-121, August(2002) Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA allele distribution and a historic perspective. Tissue Antigens 60 (2), 111–121

- ^ Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language.

- ^ Comas, David; Francesc Calafell, Eva Mateu, Anna Pérez-Lezaun, Elena Bosch, Rosa Martínez-Arias, Jordi Clarimon, Fiorenzo Facchini, Giovanni Fiori, Donata Luiselli, Davide Pettener; Jaume Bertranpetit (1998), "Trading Genes along the Silk Road: mtDNA Sequences and the Origin of Central Asian Populations", The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 1824–1838, doi:10.1086/302133

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia. Department of Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford, CA 94305-5120, USA.

- ^ American Journal Of Physical Anthropology 115:144–156 (2001) - "DNA Diversity and Population Admixture in Anatolia". pdf document

- ^ The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity

- ^ Alu insertion polymorphisms and an assessment of the genetic contribution of Central Asia to Anatolia with respect to the Balkans.

- ^ Keyser-Tracqui C., Crubezy E., Ludes B. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia American Journal of Human Genetics 2003 August; 73(2): 247–260.

- ^ The Gök Türk Empire All Empires

- ^ Nancy Touchette Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave "Skeletons from the most recent graves also contained DNA sequences similar to those in people from present-day Turkey. This supports other studies indicating that Turkic tribes originated at least in part in Mongolia at the end of the Xiongnu period."

- ^ Christine Keyser-Tracqui, Eric Crubézy, and Bertrand Ludes. Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of a 2,000-Year-Old Necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia American Journal of Human Genetics 73:247–260, 2003.

- ^ Nancy Touchette. Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave, Genome News Network.

External links

- Turkey: Country Studies from the US Library of Congress

- BBC News Country Profile for Turkey

- Cultural Exchange Programs in Turkey

- Council of Europe's Turkey Page

- Template:En iconTemplate:Tr icon Ulu Cami: A Turkish Mosque serving Muslim Community in Northern Jersey

- Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Anatolian Peninsula (Turkey)

- Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia