Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation (colloquially quitting smoking) is the process of discontinuing the practice of inhaling a smoked substance.[1] This article focuses exclusively on cessation of tobacco smoking; however, the methods described may apply to cessation of smoking other substances that can be difficult to stop using due to the development of strong physical substance dependence or psychological dependence.

Smoking cessation can occur without assistance from health care professionals or the use of medications.[2] Methods that have been found to be effective include interventions aimed at health care providers and health care systems; medications including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and varenicline; individual and group counseling; and Web-based and computer programs. Although stopping smoking can cause side effects such as weight gain, smoking cessation programs are cost-effective because of the positive health benefits.

Smoking addiction

Tobacco contains the chemical nicotine. Smoking cigarettes leads to a dependence on nicotine. Cessation of smoking leads to physiological symptoms of withdrawal.[citation needed] Methods of smoking cessation must address this dependency and subsequent withdrawal symptoms.

Methods of smoking cessation

Major reviews of the scientific literature on smoking cessation include:

- Systematic reviews of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group of the Cochrane Collaboration.[3] As of 2011, this independent, international, not-for-profit organization has published over 60 systematic reviews "on interventions to prevent and treat tobacco addiction"[3] which will be referred to as "Cochrane reviews."

- Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, which will be referred to as the "2008 Guideline."[4] The Guideline was originally published in 1996[5] and revised in 2000[6]. For the 2008 Guideline, experts screened over 8700 research articles published between 1975 and 2007.[4]: 13–14 More than 300 studies were used in meta-analyses of relevant treatments; an additional 600 reports were not included in meta-analyses, but helped formulate the recommendations.[4]: 22 Limitations of the 2008 Guideline include its not evaluating studies of "cold turkey" methods ("unaided quit attempts") and its focus on studies that followed up subjects only to about 6 months after the "quit date" (even though almost one-third of former smokers who relapse before one year will do so 7–12 months after the "quit date").[4]: 19, 23 [7][8]

Unassisted methods

Analyzing a 1986 U.S. survey, Fiore et al. (1990) found that 95% of former smokers who had been abstinent for 1-10 years had made an unassisted last quit attempt.[9] The most frequent unassisted methods were "cold turkey" and "gradually decreased number" of cigarettes.[9] A 1995 meta-analysis estimated that the quit rate from unaided methods was 7.3% after an average of 10 months of follow-up.[10] Another estimate is that "only about 4% to 7% of people are able to quit smoking on any given attempt without medicines or other help."[11]

Cold turkey

"Cold turkey" is abrupt cessation of all nicotine use. In three studies, it was the quitting method used by 76%[12], 85%[9], or 88%[13] of long-term successful quitters. In a large British study of ex-smokers in the 1980s, before the advent of pharmacotherapy, 53% of the ex-smokers said that it was “not at all difficult” to stop, 27% said it was “fairly difficult”, and the remainder found it very difficult.[2] Cold turkey methods have been advanced by J. Wayne McFarland and Elman J. Folkenburg[14][15]; Joel Spitzer and John R. Polito[16]; and Allen Carr[17].

Cut down to quit

Gradual reduction involves slowly reducing one's daily intake of nicotine. This can be done in three ways: (a) by repeated changes to cigarettes with lower levels of nicotine, (b) by gradually reducing the number of cigarettes smoked each day, or (c) by smoking only a fraction of a cigarette each time lighting up. As of 2010, and unlike earlier studies which claimed some benefit for gradual reduction, a Cochrane review found that abrupt cessation and gradual reduction with pre-quit NRT produced similar quit rates.[18][19]

Health care provider and system interventions

Interventions related to health care providers and health care systems have been shown to improve smoking cessation among people who visit those providers.

- A clinic screening system (e.g., computer prompts) to identify whether or not a person smokes doubled abstinence rates, from 3.1% to 6.4%.[4]: 78–79 Similarly, the Task Force on Community Preventive Services determined that provider reminders alone or with provider education are effective in promoting smoking cessation.[20]: 33–38

- A 2008 Guideline meta-analysis estimated that physician advice to quit smoking led to a quit rate of 10.2%, as opposed to a quit rate of 7.9% among patients who did not receive physician advice to quit smoking.[4]: 82–83 A Cochrane review found that even brief advice from physicians had "a small effect on cessation rates."[21] However, one study from Ireland involving vignettes found that physicians' probability of giving smoking cessation advice declines with the patient's age[22], and another study from the U.S. found that only 81% of smokers age 50 or greater received advice on quitting from their physicians in the preceding year.[23]

- For person-to-person counseling sessions, the duration of each session, the total amount of contact time, and the number of sessions all correlated with the effectiveness of smoking cessation. For example, "Higher intensity counseling (>10 minutes)" produced a quit rate of 22.1% as opposed to 10.9% for "no contact"; over 300 minutes of contact time produced a quit rate of 25.5% as opposed to 11.0% for "no minutes"; and more than 8 sessions produced a quit rate of 24.7% as opposed to 12.4% for 0–1 sessions.[4]: 83–86

- Both physicians and nonphysicians increased abstinence rates compared with self-help or no clinicians.[4]: 87–88 For example, a Cochrane review of 31 studies found that nursing interventions increased the likelihood of quitting by 28%.[24]

- According to the 2008 Guideline, based on two studies the training of clinicians in smoking cessation methods may increase abstinence rates[4]: 130 ; however, a Cochrane review found "no strong evidence" that such training decreased smoking in patients[25].

- Reducing or eliminating the costs of cessation therapies for smokers increased quit rates in three meta-analyses.[4]: 139–140 [20]: 38–40 [26]

Pharmacological

The American Cancer Society estimates that "between about 25% and 33% of smokers who use medicines can stay smoke-free for over 6 months."[11] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved seven medications for treating nicotine addiction. All of these helped with withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): Five of the approved medications are different methods of delivering nicotine in a form that does not involve the risks of smoking. The five NRT medications, which in a Cochrane review increased the chances of stopping smoking by 50 to 70% compared to placebo or to no treatment,[27] are:

- transdermal nicotine patches deliver doses of the addictive chemical nicotine, thus reducing the unpleasant effects of nicotine withdrawal. These patches can give smaller and smaller doses of nicotine, slowly reducing dependence upon nicotine and thus tobacco. A Cochrane review found further increased chance of success in a combination of the nicotine patch and a faster acting form.[27] Also, this method becomes most effective when combined with other medication and psychological support.[28]

- gum

- lozenges

- sprays

- inhalers.

- A study found that 93 percent of over-the-counter NRT users relapse and return to smoking within six months.[29] A 2009 systematic review by researchers at the University of Birmingham found that gradual nicotine replacement therapy was effective in smoking cessation.[30][31]

- Antidepressant: Bupropion is marketed under the brand name Zyban.

Bupropion is contraindicated in epilepsy, seizure disorder; anorexia/bulimia (eating disorders), patients' use of antidepressant drugs (MAO inhibitors) within 14 days, patients undergoing abrupt discontinuation of ethanol or sedatives (including benzodiazepines such as Valium)[32][33] - Nicotinic receptor partial agonists:

- Cytisine (Tabex) is a plant extract that has been in use since the 1960s in former Soviet-bloc countries.[34] It was the first medication approved as an aid to smoking cessation, and has very few side effects in small doses.[35][36]: 70 As of 2011 a Cochrane review stated that the evidence for the effectiveness of cytisine is "inconclusive"[37]

- Varenicline tartrate is a prescription drug marketed by Pfizer as Chantix in the U.S. and as Champix outside the U.S.[38] Synthesized as an improvement upon cytisine[39], varenicline decreases the urge to smoke and reduces withdrawal symptoms[40]. Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses supported by unrestricted funding from Pfizer, one in 2006[41] and one in 2009[42], found varenicline more effective than NRT or bupropion. A table in the 2008 Guideline indicates that 2 mg/day of varenicline leads to the highest abstinence rate (33.2%) of any single therapy, while 1 mg/day leads to an abstinence rate of 25.4%.[4]: 109 A 2011 Cochrane review of 15 studies (13 of which had been sponsored by Pfizer) found that varenicline was significantly superior to bupropion at one year but that varenicline and nicotine patches produced the same level of abstinence at 24 weeks.[37] Varenicline may cause neuropsychiatric side effects; for example, in 2008 the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued a warning about possible suicidal thoughts and suicidal behavior associated with varenicline.[43]

Two other medications have been used in trials for smoking cessation, although they are not approved by the FDA for this purpose. They may be used under careful physician supervision if the first line medications are contraindicated for the patient.

- Clonidine may reduce withdrawal symptoms and "approximately doubles abstinence rates when compared to a placebo," but its side effects include dry mouth and sedation, and abruptly stopping the drug can cause high blood pressure and other side effects.[4]: 55, 116–117 [44]

- Nortriptyline, another antidepressant, has similar success rates to bupropion but has side effects including dry mouth and sedation[33][4]: 56, 117–118 .

Community interventions

A Cochrane review concluded that there was "limited evidence" that community interventions using "multiple channels to provide reinforcement, support and norms for not smoking" had an effect on smoking cessation among adults.[45] Specific methods used in the community to encourage smoking cessation among adults include:

- Policies making workplaces[12] and public places smoke-free. It is estimated that "comprehensive clean indoor laws" can increase smoking cessation rates by 12%–38%.[46]

- Voluntary rules making homes smoke-free, which are thought to promote smoking cessation.[12][47]

- Initiatives to educate the public regarding the health effects of secondhand smoke

- Increasing the price of tobacco products, for example by taxation. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services found "strong scientific evidence" that this is effective in increasing tobacco use cessation.[20]: 28–30 It is estimated that an increase in price of 10% will increase smoking cessation rates by 3–5%.[46]

- Mass media campaigns. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services declared that "strong scientific evidence" existed for these when "combined with other interventions"[20]: 30–32 , but a Cochrane review concluded that it was "difficult to establish their independent role and value"[48].

Competitions and incentives

One 2008 Cochrane review concluded that "incentives and competitions have not been shown to enhance long-term cessation rates."[49] However, a randomized trial published in 2009 found that financial incentives for smoking cessation led to significantly higher rates of smoking cessation 15-18 months after enrollment.[50] Furthermore, a different 2008 Cochrane review found that one type of competition, "Quit and Win," did increase quit rates among participants.[51]

Psychosocial approaches

- Great American Smokeout is an annual event that invites smokers to quit for one day, hoping they will be able to extend this forever.

- The World Health Organization's World No Tobacco Day is held on May 31 each year.

- Smoking-cessation support and counseling is often offered over the internet, over phone quitlines[52][53] (e.g., the US toll-free number 1-800-QUIT-NOW), or in person. Three meta-analyses have concluded that telephone cessation counseling is effective when compared with minimal or no counseling or self-help, and that telephone cessation counseling with medication is more effective than medication alone.[4]: 91–92 [20]: 40–42 [54]

- Group or individual counseling can help people who want to quit. Counseling is effective alone; counseling and medication is more effective than medication alone (and conversely, medication and counseling is more effective than counseling alone); and the number of sessions of counseling with medication correlates with effectiveness.[4]: 89–90, 101–103 [55][56] The types of counseling that have been effective in smoking cessation programs include motivational interviewing[57][58][59] and cognitive behavioral therapy[60].

- Multiple formats of psychosocial interventions increase quit rates: 10.8% for no intervention, 15.1% for one format, 18.5% for 2 formats, and 23.2% for three or four formats.[4]: 91

- The Transtheoretical Model including "stages of change" has been used in tailoring smoking cessation methods to individuals.[61][62][63][64] However, a 2010 Cochrane review concluded that "stage-based self-help interventions (expert systems and/or tailored materials) and individual counselling were neither more nor less effective than their non-stage-based equivalents."[65]

Self-help

A 2005 Cochrane review found that self-help materials may produce only a small increase in quit rates.[66] In the 2008 Guideline, "the effect of self-help was weak," and the number of types of self-help did not produce higher abstinence rates.[4]: 89–91 Nevertheless, self-help modalities for smoking cessation include:

- In-person self-help groups such as Nicotine Anonymous[67][68] or electronic self-help groups such as Stomp It Out[69].

- Newsgroups: The Usenet group alt.support.stop-smoking has been used by people quitting smoking as a place to go to for support from others.[70] It is accessible through Google Groups.[71]

- Interactive web- and computer-based programs that assist participants in quitting. For example, "quit meters" keep track of statistics such as how long a person has remained abstinent.[72] In the 2008 Guideline, there was no meta-analysis of computerized interventions, but they were described as "highly promising."[4]: 93–94 A meta-analysis published in 2009[73] and a Cochrane review published in 2010[74] noted that the scientific evidence for such programs was "sufficient" but "did not show consistent effects."

- Mobile phone-based interventions: A 2009 Cochrane review stated that "more evidence is needed" to determine the effectiveness of such interventions.[75] As of 2009, a randomized trial of mobile phone-based smoking cessation support was underway in the U.K.[76]

- Self-help books such as Allen Carr's Easy Way to Stop Smoking.[17]

- Spirituality: In one survey of adult smokers, 88% reported a history of spiritual practice or belief, and of those more than three-quarters were of the opinion that using spiritual resources may help them quit smoking.[77]

Substitutes for cigarettes

- Electronic cigarette: Shaped like a cigar or cigarette to satisfy habitual tactile cravings, this device contains a rechargeable battery and a heating element that vaporizes liquid nicotine (and other flavorings) from an insertable cartridge, at lower initial cost than a vaporizer but with similar advantages including significantly reducing tar and carbon monoxide. In September 2008, the World Health Organization issued a release proclaiming that it does not consider the electronic cigarette to be a legitimate smoking cessation aid, stating that to its knowledge, "no rigorous, peer-reviewed studies have been conducted showing that the electronic cigarette is a safe and effective nicotine replacement therapy."[78]

- Plastic cigarette substitute: In one 2006 study, giving people a free "Better Quit" hollow tube resembling a cigarette did not improve quit rates.[79]

Alternative approaches

- Acupuncture. A Cochrane review concludes that acupuncture "do[es] not appear to help smokers who are trying to quit"[80], a meta-analysis from the 2008 Guideline showed no difference between acupuncture and placebo[4]: 99–100 , and the 2008 Guideline found no scientific studies supporting laser therapy based on acupuncture principles but without the needles.[4]: 99 . Nevertheless, acupuncture has been called a "reasonable option" for smoking cessation because of its low risk[81].

- Aromatherapy. A 2006 book reviewing the scientific literature on aromatherapy[82] identified only one study on smoking cessation and aromatherapy; the study concerned black pepper oil.[83]

- Hypnosis. Clinical trials studying hypnosis and hypnotherapy as a method for smoking cessation have been inconclusive[4]: 100 [84]; however, a randomized trial published in 2008 found that hypnosis and nicotine patches "compares favorably" with standard behavioral counseling and nicotine patches in 12-month quit rates[85].

Smoking cessation in special populations

Children and adolescents

Methods used with children and adolescents include:

- Motivational enhancement[86]

- Psychological support[86]

- Youth anti-tobacco activities, such as sport involvement

- School-based curriculum, such as life-skills training [1]

- Access reduction to tobacco

- Anti-tobacco media [2] and [3]

- Family communication

A Cochrane review, mainly of studies combining motivational enhancement and psychological support, concluded that "complex approaches" for smoking cessation among young people show promise.[86] The 2008 Guideline recommends counseling for adolescent smokers on the basis of a meta-analysis of seven studies.[4]: 159–161 Neither the Cochrane review nor the 2008 Guideline recommends medications for adolescents who smoke.

Pregnant women

Smoking during pregnancy can cause adverse health effects in both the woman and the fetus. The 2008 Guideline determined that "person-to-person psychosocial interventions" (typically including "intensive counseling") increased abstinence rates in pregnant women who smoke to 13.3%, compared with 7.6% in usual care.[4]: 165–167

Workers

A 2008 Cochrane review of smoking cessation programs in workplaces concluded that "interventions directed towards individual smokers increase the likelihood of quitting smoking."[87] A 2010 systematic review determined that worksite incentives and competitions needed to be combined with additional interventions to produce significant increases in smoking cessation rates.[88]

Hospitalized smokers

People who smoke who are hospitalized may be particularly motivated to quit.[4]: 149–150 A 2007 Cochrane review found that interventions beginning during a hospital stay and continuing for one month or more after discharge were effective in producing abstinence.[89]

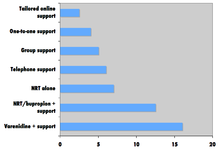

Comparison of success rates

Comparison of success rates across interventions can be difficult because of different definitions of "success" across studies.[11] Robert West and Saul Shiffman have authored works on smoking cessation. They believe that, used together, "behavioral support" and "medication" can quadruple the chances that a quit attempt will be successful. Both, however, disclosed that they are paid researchers or consultants to pharmaceutical companies or manufacturers of smoking cessation medications.[36]: 73, 76, 80

A 2008 systematic review in the European Journal of Cancer Prevention found that group behavioral therapy was the most effective intervention strategy for smoking cessation, followed by bupropion, intensive physician advice, nicotine replacement therapy, individual counseling, telephone counseling, nursing interventions, and tailored self-help interventions; the study did not discuss varenicline.[46]

In 2010 the National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative (NTCC) created What Works to Quit: A Guide to Quit Smoking Methods, which compares the efficacy and cost of 17 smoking cessation methods. The guide, based on the 2008 Guideline, reports that smokers using a combination method of pharmacological and psychosocial approaches have the most success compared to those who use pharmaceutical or psychosocial approaches in isolation.[90]

Factors affecting success

Quitting can be harder for individuals with dark pigmented skin compared to individuals with pale skin since nicotine has an affinity for melanin-containing tissues. Studies suggest this can cause the phenomenon of increased nicotine dependence and lower smoking cessation rate in darker pigmented individuals.[92]

There is an important social component to smoking. A 2008 study analyzing a densely interconnected network of over 12,000 individuals found that smoking cessation by any given individual reduced the chances of others around them lighting up by the following amounts: a spouse by 67%, a sibling by 25%, a friend by 36%, and a coworker by 34%.[93] Nevertheless, a Cochrane review determined that interventions to increase social support for a smoker's cessation program did not increase long-term quit rates.[94]

Smokers with major depressive disorder are less successful at quitting smoking than non-depressed smokers.[4]: 81 [95]

Side effects

Symptoms

In a 2007 review of the effects of abstinence from tobacco, Hughes concluded that "anger, anxiety, depression, difficulty concentrating, impatience, insomnia, and restlessness are valid withdrawal symptoms that peak within the first week and last 2–4 weeks."[33] In contrast, "constipation, cough, dizziness, increased dreaming, and mouth ulcers" may or may not be symptoms of withdrawal, while drowsiness, fatigue, and certain physical symptoms ("dry mouth, flu symptoms, headaches, heart racing, skin rash, sweating, tremor") were not symptoms of withdrawal.[33]

Weight gain

People who successfully quit smoking may gain weight. In a 1991 study that found that the mean weight gain due to smoking cessation was 2.8 kg (6.2 lb) for men and 3.8 kg (8.4 lb) for women, the researchers concluded "weight gain is not likely to negate the health benefits of smoking cessation, but its cosmetic effects may interfere with attempts to quit."[96]

The causes of the weight gain are unclear, but hypotheses include:

- Smoking over expresses the gene AZGP1 which stimulates lipolysis, so smoking cessation may decrease lipolysis.[97]

- Smoking suppresses appetite, which may be caused by nicotine's effect on central autonomic neurons (e.g., via regulation of melanin concentrating hormone neurons in the hypothalamus).[98]

- Heavy smokers are reported to burn 200 calories per day more than non-smokers eating the same diet.[99] Possible reasons for this phenomenon include nicotine's ability to increase energy metabolism or nicotine's effect on peripheral neurons.[98]

The 2008 Guideline suggests that sustained-release bupropion, nicotine gum, and nicotine lozenge be used "to delay weight gain after quitting."[4]: 173–176 However, a 2009 Cochrane review concluded that "The data are not sufficient to make strong clinical recommendations for effective programmes" for preventing weight gain.[100]

Depression

When people with a history of depression stop smoking, depressive symptoms or actual depression may result.[95][101] This side effect of smoking cessation may be particularly common in women, as depression is more common among women than among men.[102]

Health benefits

Many of tobacco's health effects can be minimized through smoking cessation. The health benefits over time of stopping smoking include[103]:

- Within 20 minutes after quitting, blood pressure and heart rate decrease

- Within 12 hours, carbon monoxide levels in the blood decrease to normal

- Within 3 months, circulation and lung function improve

- Within 9 months, there are decreases in cough and shortness of breath

- Within 1 year, the risk of coronary heart disease is cut in half

- Within 5 years, the risk of stroke falls to the same as a non-smoker, and the risks of many cancers (mouth, throat, esophagus, bladder, cervix) decrease significantly

- Within 10 years, the risk of dying from lung cancer is cut in half[104], and the risks of larynx and pancreas cancers decrease

- Within 15 years, the risk of coronary heart disease drops to the level of a non-smoker

The British doctors study showed that those who stopped smoking before they reached 30 years of age lived almost as long as those who never smoked.[105] Stopping in one's sixties can still add three years of healthy life.[105] A randomized trial from the U.S. and Canada showed that a smoking cessation program lasting 10 weeks decreased mortality from all causes over 14 years later.[106]

Cost-effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness analyses of smoking cessation programs have shown that they increase quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at costs comparable with other types of interventions to treat and prevent disease.[4]: 134–137 Studies of the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation include:

- In a 1997 U.S. analysis, the estimated cost per QALY varied by the type of program, ranging from group intensive counseling without nicotine replacement at $1108 per QALY to minimal counseling with nicotine gum at $4542 per QALY.[107]

- A study from Erasmus University Rotterdam limited to people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease found that the cost-effectiveness of minimal counseling, intensive counseling, and drug therapy were €16,900, €8,200, and €2,400 per QALY gained respectively.[108]

- Among National Health Service smoking cessation clients in Glasgow, pharmacy one-to-one counseling cost £2,600 per QALY gained and group support cost £4,800 per QALY gained.[109]

Statistics

In a growing number of countries, there are more ex-smokers than smokers.[2] For example, in the U.S. as of 2010, there were 47 million ex-smokers and 46 million smokers.[110]

See also

- American Legacy Foundation

- Carbon monoxide breath monitor

- Coerced abstinence

- Bijan Daneshmand

- Electronic cigarette

- Health promotion

- Herbal tobacco alternatives

- List of smoking bans in the United States

- Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program (MTCP)

- National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

- Nicotine Anonymous

- Nicotine replacement therapy

- NicVAX

- Smoking cessation (cannabis)

- Smoking cessation programs in Canada

- Tobacco and health

- Tobacco cessation clinic

- U.S. government and smoking cessation

- Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

Notes

- ^ "Guide to quitting smoking". American Cancer Society. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ a b c Chapman S, MacKenzie R (2010 February 9). "The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences". PLoS Medicine. 7 (2). Public Library of Science: e1000216. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000216. PMC 2817714. PMID 20161722.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group (2010 March 2). "Welcome". Retrieved 2011-02-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB; et al. (2008). Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ; et al. (1996). Smoking cessation. Clinical practice guideline no. 18. AHCPR publication no. 96-0692. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ; et al. (2000). Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Associated Press (2008 May 7). "Conflict over officials' stop-smoking advice". msnbc.com. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, Judge K (2005). "The English smoking treatment services: one-year outcomes" (PDF). Addiction. 100 (Suppl 2): 59–69. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01028.x. PMID 15755262.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, Giovino GA, Hatziandreu EJ, Newcomb PA, Surawicz TS, Davis RM (1990). "Methods used to quit smoking in the United States. Do cessation programs help?" (PDF). JAMA. 263: 2760–5. PMID 2271019. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baillie AJ, Mattick RP, Hall W (1995). "Quitting smoking: estimation by meta-analysis of the rate of unaided smoking cessation". Aust J Public Health. 19: 129–31. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00361.x. PMID 7786936.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Guide to quitting smoking. A word about quitting success rates". American Cancer Society. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ a b c Lee CW, Kahende J (2007). "Factors associated with successful smoking cessation in the United States, 2000". Am J Public Health. 97: 1503–9. PMID 17600268. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ Doran CM, Valenti L, Robinson M, Britt H, Mattick RP (2006). "Smoking status of Australian general practice patients and their attempts to quit". Addict Behav. 31: 758–66. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.054. PMID 16137834.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "New book details history of LLU bringing 'Health to the People'". Loma Linda University. 2008 March 31. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ McFarland JW, Folkenberg EJ (1964). How to stop smoking in five days. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ^ "WhyQuit". WhyQuit. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ a b Carr A (2004). The easy way to stop smoking. New York: Sterling. ISBN 1402771630.

- ^ Joseph J (March 30, 2010). "Cut down to quit approach no better". Pharmacy News. Reed Business Information.

- ^ Lindson N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR (2010). "Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD008033. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008033.pub2. PMID 20238361. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Hopkins DP, Briss PA, Ricard CJ, Husten CG, Carande-Kulis VG, Fielding JE, Alao MO, McKenna JW, Sharp DJ, Harris JR, Woollery TA, Harris KW; Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2001). "Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke" (PDF). Am J Prev Med. 20 (2 Suppl): 16–66. PMID 11173215.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T (2008). "Physician advice for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000165. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. PMID 18425860.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maguire CP, Ryan J, Kelly A, O'Neill D, Coakley D, Walsh JB (2000). "Do patient age and medical condition influence medical advice to stop smoking?". Age Ageing. 29: 264–6. PMID 10855911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ossip-Klein DJ, McIntosh S, Utman C, Burton K, Spada J, Guido J (2000). "Smokers ages 50+: who gets physician advice to quit?" (PDF). Prev Med. 31: 364–9. doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.0721. PMID 11006061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rice VH, Stead LF (2008). "Nursing interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001188. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub3. PMID 18253987.

- ^ Lancaster T, Silagy C, Fowler G (2000). "Training health professionals in smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD000214. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000214. PMID 10908465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reda AA, Kaper J, Fikrelter H, Severens JL, van Schayck CP (2009). "Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004305. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004305.pub3. PMID 19370599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Lancaster T (2008). "Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation" (1). Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub3. PMID 18253970. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Noble HB (1999 March 2). "New from the smoking wars: success". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Millstone K (2007 February 13). "Nixing the patch: Smokers quit cold turkey". Columbia.edu News Service. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Phend C (2009 April 3). "Gradual cutback with nicotine replacement boosts quit rates". MedPage Today. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Moore D, Aveyard P, Connock M, Wang D, Fry-Smith A, Barton P (2009). "Effectiveness and safety of nicotine replacement therapy assisted reduction to stop smoking: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 338: b1024. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1024. PMID 19342408.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lacy CF; et al. (2004). Drug information handbook (12th ed.). Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp. ISBN 1-59195-083-X.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c d Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T (2007). "Antidepressants for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub3. PMID 17253443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Hughes2007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Etter JF, Lukas RJ, Benowitz NL, West R, Dresler CM (2008). "Cytisine for smoking cessation: a research agenda". Drug Alcohol Depend. 92: 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.017. PMID 17825502.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herrick C, Herrick C, Mitchell M (2009). 100 questions & answers about how to quit smoking. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 112. ISBN 0763757411.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c West R, Shiffman S (2007). Fast facts: smoking cessation (2nd ed.). Abingdon, England: Health Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-903734-98-8.

- ^ a b Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T (2011). "Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006103. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub5. PMID 21328282. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pfizer (2009). "Doing things differently. Annual review 2008" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ Yarnell A (2005 May 31). "Design of an antismoking pill. The makers of varenicline got their inspiration from two natural products". Chemical & Engineering News. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pfizer Canada Inc (2010 May 28). "Product monograph. PrChampix® (varenicline tartrate tablets)". Retrieved 2011-02-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wu P, Wilson K, Dimoulas P, Mills EJ (2006). "Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a". BMC Public Health. 6: 300. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-300. PMID 17156479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mills EJ, Wu P, Spurden D, Ebbert JO, Wilson K (2009). "Efficacy of pharmacotherapies for short-term smoking abstinance: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Harm Reduct J. 6: 25. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-25. PMID 19761618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2008 July). "Drug safety advice. Varenicline: suicidal thoughts and behaviour" (PDF). Drug Safety Update. 1 (12): 2–3. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gourlay SG, Stead LF, Benowitz NL (2004). "Clonidine for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD000058. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000058.pub2. PMID 15266422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Secker-Walker RH, Gnich W, Platt S, Lancaster T (2002). "Community interventions for reducing smoking among adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001745. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001745. PMID 12137631.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lemmens V, Oenema A, Knut IK, Brug J (2008). "Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among adults: a systematic review of reviews" (PDF). Eur J Cancer Prev. 17: 535–44. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e48. PMID 18941375.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). State-specific prevalence of smoke-free home rules--United States, 1992–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:501–4. PMID 17522588

- ^ Bala M, Strzeszynski L, Cahill K (2008). "Mass media interventions for smoking cessation in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD004704. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004704.pub2. PMID 18254058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cahill K, Perera R (2008). "Competitions and incentives for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD004307. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004307.pub3. PMID 18646105.

- ^ Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, Galvin R, Zhu J, Wan F, DeGuzman J, Corbett E, Weiner J, Audrain-McGovern J (2009). "A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation". N Engl J Med. 360: 699–709. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. PMID 19213683.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cahill K, Perera R (2008). "Quit and Win contests for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004986. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004986.pub3. PMID 18843674.

- ^ Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, Rosbrook B, Johnson CE, Byrd M, Gutiérrez-Terrell E (2002). "Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers". N Engl J Med. 347: 1087–93. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa020660. PMID 12362011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Helgason AR, Tomson T, Lund KE, Galanti R, Ahnve S, Gilljam H (2004). "Factors related to abstinence in a telephone helpline for smoking cessation" (PDF). Eur J Public Health. 14: 306–10. PMID 15369039.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T (2006). "Telephone counselling for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD002850. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub2. PMID 16855992.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stead LF, Lancaster T (2005). "Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001007. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub2. PMID 15846610.

- ^ Lancaster T, Stead LF (2005). "Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001292. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub2. PMID 15846616.

- ^ Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y, Tang JL (2010). "Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD006936. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub2. PMID 20091612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hettema JE, Hendricks PS (2010). "Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a meta-analytic review". J Consult Clin Psychol. 78: 868–84. doi:10.1037/a0021498. PMID 21114344.

- ^ Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Hofmann MT (2010). "Efficacy of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Tob Control. 19: 410–6. doi:10.1136/tc.2009.033175. PMID 20675688.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Perkins KA, Conklin CA, Levine MD (2008). New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415954631.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava J (1988). "Measuring processes of change: applications to the cessation of smoking". J Consult Clin Psychol. 56: 520–8. PMID 3198809.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS (1991). "The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change" (PDF). J Consult Clin Psychol. 59: 295–304. PMID 2030191. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG (1992). "Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies". Psychol Bull. 111: 23–41. PMID 1539088.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Velicer WF, Rossi JS (1993). "Standardized, individualized, interactive, and personalized self-help programs for smoking cessation" (PDF). Health Psychol. 12: 399–405. PMID 8223364. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cahill K, Lancaster T, Green N (2010). "Stage-based interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11): CD004492. PMID 21069681. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lancaster T, Stead LF (2005). "Self-help interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001118. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001118.pub2. PMID 16034855.

- ^ "Nicotine Anonymous (official website)". Dallas, TX: Nicotine Anonymous World Services. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Glasser I (2010). "Nicotine Anonymous may benefit nicotine-dependent individuals". Am J Public Health. 100: 196. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.181545. PMID 20019295.

- ^ "Stomp It Out". San Francisco, CA: Experience Project. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Uhler D (1995 November 15). "Breaking the habit - these tips can keep your good intentions from going up in smoke". San Antonio Express-News.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Google Groups. "alt.support.stop-smoking". Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Hendrick B (2009 May 26). "Computer is an ally in quit-smoking fight. Study shows web- and computer-based programs help smokers quit". WebMD Health News. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Myung SK, McDonnell DD, Kazinets G, Seo HG, Moskowitz JM (2009). "Effects of Web- and computer-based smoking cessation programs: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Arch Intern Med. 169: 929–37. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.109. PMID 19468084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Civljak M, Sheikh A, Stead LF, Car J (2010). "Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9): CD007078. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub3. PMID 20824856.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Whittaker R, Borland R, Bullen C, Lin RB, McRobbie H, Rodgers A (2009). "Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD006611. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub2. PMID 19821377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Free C, Whittaker R, Knight R, Abramsky T, Rodgers A, Roberts IG (2009). "Txt2stop: a pilot randomised controlled trial of mobile phone-based smoking cessation support". Tob Control. 18: 88–91. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.026146. PMID 19318534.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gonzales D, Redtomahawk D, Pizacani B, Bjornson WG, Spradley J, Allen E, Lees P (2007). "Support for spirituality in smoking cessation: results of pilot survey". Nicotine Tob Res. 9: 299–303. doi:10.1080/14622200601078582. PMID 17365761.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Marketers of electronic cigarettes should halt unproved therapy claims". World Health Organization. 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Bauer JE, Carlin-Menter SM, Celestino PB, Hyland A, Cummings KM (2006). "Giving away free nicotine medications and a cigarette substitute (Better Quit) to promote calls to a quitline". J Public Health Manag Pract. 12: 60–7. PMID 16340517.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ White AR, Rampes H, Liu JP, Stead LF, Campbell J (2011). "Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000009.pub3. PMID 21249644. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith TJ, Schwartz-Smith T (2009). "Acupuncture and smoking cessation" (PDF). S D Med (Spec No): 57–8. PMID 19363896. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ Lis-Balchin M (2006). Aromatherapy science: a guide for healthcare professionals. London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 101. ISBN 0853695784.

- ^ Rose JE, Behm FM (1994). "Inhalation of vapor from black pepper extract reduces smoking withdrawal symptoms". Drug Alcohol Depend. 34: 225–9. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(94)90160-0. PMID 8033760.

- ^ Barnes J, Dong CY, McRobbie H, Walker N, Mehta M, Stead LF (2010). "Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (10): CD001008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001008.pub2. PMID 20927723.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carmody TP, Duncan C, Simon JA, Solkowitz S, Huggins J, Lee S, Delucchi K (2008). "Hypnosis for smoking cessation: a randomized trial". Nicotine Tob Res. 10: 811–8. doi:10.1080/14622200802023833. PMID 18569754.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Grimshaw GM, Stanton A (2006). "Tobacco cessation interventions for young people". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. PMID 17054164.

- ^ Cahill K, Moher M, Lancaster T (2008). "Workplace interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003440. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003440.pub3. PMID 18843645.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leeks KD, Hopkins DP, Soler RE, Aten A, Chattopadhyay SK; Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2010). "Worksite-based incentives and competitions to reduce tobacco use. A systematic review" (PDF). Am J Prev Med. 38 (2 Suppl): S263–74. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.034. PMID 20117611.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF (2007). "Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001837. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub2. PMID 17636688.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "What Works To Quit" (PDF). The National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A (2007). "Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking". Science. 315: 531–4. doi:10.1126/science.1135926. PMID 17255515.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ King G, Yerger VB, Whembolua GL, Bendel RB, Kittles R, Moolchan ET (2009). "Link between facultative melanin and tobacco use among African Americans" (PDF). Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 92: 589–96. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2009.02.011. PMID 19268687.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Christakis NA, Fowler JH (2008). "The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network". N Engl J Med. 358: 2249–58. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. PMID 18499567.

- ^ Park EW, Schultz JK, Tudiver F, Campbell T, Becker L (2004). "Enhancing partner support to improve smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD002928. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002928.pub2. PMID 15266469.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J (1990). "Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression" (PDF). JAMA. 264: 1546–9. PMID 2395194.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williamson DF, Madans J, Anda RF, Kleinman JC, Giovino GA, Byers T (1991). "Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort". N Engl J Med. 324: 739–45. doi:10.1056/NEJM199103143241106. PMID 1997840.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vanni H, Kazeros A, Wang R, Harvey BG, Ferris B, De BP, Carolan BJ, Hübner RH, O'Connor TP, Crystal RG (2009). "Cigarette smoking induces overexpression of a fat-depleting gene AZGP1 in the human". Chest. 135: 1197–208. doi:10.1378/chest.08-1024. PMC 2679098. PMID 19188554.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jo YH, Talmage DA, Role LW (2002). "Nicotinic receptor-mediated effects on appetite and food intake". J Neurobiol. 53: 618–32. doi:10.1002/neu.10147. PMC 2367209. PMID 12436425.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klag MJ (1999). Johns Hopkins family health book. New York: HarperCollins. p. 86. ISBN 0062701495.

- ^ Parsons AC, Shraim M, Inglis J, Aveyard P, Hajek P (2009). "Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD006219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006219.pub2. PMID 19160269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F (1997). "Major depression following smoking cessation". Am J Psychiatry. 154: 263–5. PMID 9016279.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Borrelli B, Bock B, King T, Pinto B, Marcus BH (1996). "The impact of depression on smoking cessation in women". Am J Prev Med. 12: 378–87. PMID 8909649.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Cancer Society (2011-01-31). "When smokers quit -- What are the benefits over time?". Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R (2000). "Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies". BMJ. 321: 323–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323. PMID 10926586. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 328: 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, Manfreda J, Kanner RE, Connett JE; Lung Health Study Research Group (2005). "The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: a randomized clinical trial". Ann Intern Med. 142: 233–9. PMID 15710956.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cromwell J, Bartosch WJ, Fiore MC, Hasselblad V, Baker T (1997). "Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation" (PDF). JAMA. 278: 1759–66. PMID 9388153.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoogendoorn M, Feenstra TL, Hoogenveen RT, Rutten-van Mölken MP (2010). "Long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in patients with COPD". Thorax. 65: 711–8. doi:10.1136/thx.2009.131631. PMID 20685746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bauld L, Boyd KA, Briggs AH, Chesterman J, Ferguson J, Judge K, Hiscock R (2011). "One-year outcomes and a cost-effectiveness analysis for smokers accessing group-based and pharmacy-led cessation services". Nicotine Tob Res. 13: 135–45. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq222. PMID 21196451.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martin A (2010 May 13). "What it takes to quit smoking". MarketWatch. Dow Jones. p. 2. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

- Henningfield J, Fant R, Buchhalter A, Stitzer M (2005). "Pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependence". CA Cancer J Clin. 55 (5): 281–99, quiz 322–3, 325. doi:10.3322/canjclin.55.5.281. PMID 16166074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99(1):29-38.

- Hutter HP, et al. Smoking cessation at the workplace: 1 year success of short seminars. International Archives of Occupational & Environmental Health. 2006;79:42-48.

- Marks DF (2005). Overcoming your smoking habit: a self-help guide using cognitive behavioral techniques. London: Robinson. ISBN 1845290674.

- Peters MJ, Morgan LC. The pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation. Med J Aust 2002;176:486-490. PMID 12065013.

- West R. Tobacco control: present and future. Br Med Bull 2006;77-78:123-36.

External links

- World Health Organization. Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI).