Herero and Nama genocide

The Herero and Namaqua Genocide is considered to have been the first genocide of the 20th century.[1][2][3][4][5] It took place between 1904 and 1907 in German South-West Africa (modern day Namibia), during the scramble for Africa.

On January 12, 1904, the Herero people, led by Samuel Maharero, rebelled against German colonial rule. In August, German general Lothar von Trotha defeated the Herero in the Battle of Waterberg and drove them into the desert of Omaheke, where most of them died of thirst. In October, the Nama people also rebelled against the Germans only to suffer a similar fate.

In total, from 24,000 up to 100,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama died.[6][7][8][9][10] The genocide was characterized by widespread death by starvation and thirst because the Herero who fled the violence were prevented from returning from the Namib Desert. Some sources also claim that the German colonial army systematically poisoned desert wells.[11][12]

In 1985, the United Nations' Whitaker Report classified the aftermath as an attempt to exterminate the Herero and Nama peoples of South-West Africa, and therefore one of the earliest attempts at genocide in the 20th century. The German government recognized and apologized for the events in 2004, but has ruled out financial compensation for the victims' descendants.[13]

Background

The Herero were originally a tribe of cattle herders living in a region of German South West Africa, presently modern Namibia. The area occupied by the Herero was known as Damaraland. In 1883, during the scramble for Africa, Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz purchased land from the Nama and, in August 1884, it was declared a German protectorate, despite the German government's knowledge that their means of acquisition were fraudulent;[14] at that time, it was the only overseas German territory deemed suitable for white settlement.[15]

Chief of the neighbouring Hereros, Kamaharero had made himself great by uniting all the Herero [citation needed]. Faced with repeated attacks by the ǀKhowesin, a subtribe of the Khoikhoi under Hendrik Witbooi, he signed a protection treaty with Imperial Germany's colonial governor Göring on 21 October 1885 but did not cede the land of the Herero. This treaty was renounced in 1888 due to lack of German support against Witbooi but it was reinstated in 1890.[16]

The Herero leaders repeatedly complained about violation of this treaty, as Herero women and girls were raped by Germans, a crime that the German authorities were reluctant to punish.[17]

In 1890 Kamaharero's son Samuel signed a great deal of land over to the Germans in return for helping him to ascend to the Ovaherero throne, and to subsequently be established as paramount chief.[18] German involvement in tribal fighting ended in tenuous peace in 1894 [citation needed]. In that year, Theodor Leutwein became governor of the territory, which underwent a period of rapid development, while the German government sent the Schutztruppe, imperial colonial troops, to pacify the region.[19]

Under German colonial rule natives were routinely used as slave labourers, and their lands were frequently confiscated and given to colonists, who were encouraged to settle on land taken from the natives;, that land was stocked with cattle stolen from the Hereros and Namas,[20][21][22][23][24][25] causing a great deal of resentment.

Eventually the area was to be inhabited predominantly by whites and become "African Germany".[26] Over the next decade, the land and the cattle that were essential to Herero and Nama lifestyles passed into the hands of German settlers arriving in South-West Africa.[27]

Revolts

In 1903, some of the Nama tribes rose in revolt under the leadership of Hendrik Witbooi.[19] A number of factors led the Herero to join them in January 1904.

One of the major issues was land rights. The Herero had already ceded over a quarter of their 130,000 square kilometres (50,000 sq mi) to German colonists by 1903,[28] before the Otavi railroad line running from the African coast to inland German settlements was completed.[29] Completion of this line would have made the German colonies much more accessible and would have ushered a new wave of Europeans into the area.[30]

Historian Horst Drechsler states that there was discussion of the possibility of establishing and placing the Herero in native reserves and that this was further proof of the German colonists' sense of ownership over the land. Drechsler illustrates the gap between the rights of a European and an African; the German Colonial League held that, in regards to legal matters, the testimony of seven Africans was equivalent to that of one white man.[31] Bridgman writes about racial tensions underlying these developments; the average German colonist viewed native Africans as a lowly source of cheap labour, and others welcomed their extermination.[28]

A new policy on debt collection, enforced in November 1903, also played a role in the uprising. For many years, the Herero population had fallen in the habit of borrowing money from white traders at great interest. For a long time, much of this debt went uncollected and accumulated, as most Hereros had no means to pay. To correct this growing problem, Governor Leutwein decreed with good intentions that all debts not paid within the next year would be voided.[32] In the absence of hard cash, traders often seized cattle, or whatever objects of value they could get their hands on, to recoup their loans as quickly as possible. This fostered a feeling of resentment towards the Germans on the part of the Herero people, which escalated to hopelessness when they saw that German officials were sympathetic to the traders who were about to lose what they were owed.[28]

In 1903 Herero learned of a plan to divide their territory by a railway line and set up reservations where they would be concentrated; this was also one of the reasons for the revolt.[33]

The Herero judged the situation intolerable, and revolted in early 1904, killing between 123 and 150 Germans, including seven Boers and three women,[34] in what Nils Ole Oermann calls a "desperate surprise attack".[35]

The timing of their attack was carefully planned. After successfully asking a large Herero tribe to surrender their weapons, Governor Leutwein was convinced that they and the rest of the native population were essentially pacified and half the German troops stationed in his colony had been withdrawn.[36] Led by Chief Samuel Maharero, they surrounded Okahandja and cut links to Windhoek, the colonial capital. Maharero issued a manifesto in which he forbade his troops the killing of Englishmen, Boers, uninvolved tribes as well as women and children in general and German missionaries.[37]

Leutwein was forced to request reinforcements and an experienced officer from the German government in Berlin.[38] Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha was appointed Supreme Commander (German: Oberbefehlshaber) of South-West Africa on 3 May, arriving with an expeditionary force of 14,000 troops on 11 June.

Leutwein was subordinate to the Colonial Department of the Prussian Foreign Office, which reported to Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow while general Trotha reported to the military German General Staff, which was only subordinate to Emperor Wilhelm II.

Leutwein wanted to defeat the most determined Herero rebels and negotiate a surrender with the remainder to achieve a political settlement.[39] Trotha, however, planned to crush the native resistance through military force. He stated that:

"My intimate knowledge of many central African tribes (Bantu and others) has everywhere convinced me of the necessity that the Negro does not respect treaties but only brute force" [40]

He also wrote that [DE 1]:

"I know enough of African tribes that they give way only to violence. To exercise this violence with crass terrorism and even with gruesomeness was and is my policy. I destroy the rebellious tribes with streams of blood and money. Only from this seed something new will emerge, which will remain." [41]

Genocide

General Trotha stated his proposed solution to end the resistance of the Herero people in a letter, before the Battle of Waterberg:[42]

"I believe that the nation as such should be annihilated, or, if this was not possible by tactical measures, have to be expelled from the country...This will be possible if the water-holes from Grootfontein to Gobabis are occupied. The constant movement of our troops will enable us to find the small groups of nation who have moved backwards and destroy them gradually."

Trotha's troops defeated 3,000–5,000 Herero combatants at the Battle of Waterberg on 11–12 August 1904 but were unable to encircle and eliminate the retreating survivors.[39]

The pursuing German forces prevented groups of Herero from breaking from the main body of the fleeing force and pushed them further into the desert, and as exhausted Herero fell to the ground unable to go on, German soldiers acting on orders killed men, women and children.[43] Jan Cloete, acting as a guide for the Germans, witnessed the atrocities committed by the German troops and deposed the following statement:[44]

"I was present when the Herero were defeated in a battle in the vicinity of Waterberg. After the battle all men, women, and children who fell into German hands, wounded or otherwise, were mercilessly put to death. Then the Germans set off in pursuit of the rest, and all those found by the wayside and in the sandveld were shot down and bayoneted to death. The mass of the Herero men were unarmed and thus unable to offer resistance. They were just trying to get away with their cattle."

A portion of the Herero escaped the Germans and went to the Omaheke Desert, hoping to reach British territory of Bechuanaland; less than 1,000 reached Bechuanaland, where they were granted asylum.[45] To prevent them from returning, Trotha ordered the desert to be sealed off.[46] German patrols later found skeletons around holes 13 m (approx. 40 ft) deep that had been dug in a vain attempt to find water.[43] Maherero and between 500 to 1,500 men crossed the Kalahari into Bechuanaland where he was accepted as a vassal of the Batswana chief Sekgoma.[47]

On 2 October, Trotha issued a warning to the Hereros [DE 2]:

I, the great general of the German soldiers, send this letter to the Hereros. The Hereros are German subjects no longer. They have killed, stolen, cut off the ears and other parts of the body of wounded soldiers, and now are too cowardly to want to fight any longer. I announce to the people that whoever hands me one of the chiefs shall receive 1,000 marks, and 5,000 marks for Samuel Maherero. The Herero nation must now leave the country. If it refuses, I shall compel it to do so with the 'long tube' (cannon). Any Herero found inside the German frontier, with or without a gun or cattle, will be executed. I shall spare neither women nor children. I shall give the order to drive them away and fire on them. Such are my words to the Herero people.[50]

He further gave orders that:

This proclamation is to read to the troops at roll-call, with the addition that the unit that catches a captain will also receive the appropriate reward, and that the shooting at women and children is to be understood as shooting above their heads, so as to force them to run [away]. I assume absolutely that this proclamation will result in taking no more male prisoners, but will not degenerate into atrocities against women and children. The latter will run away if one shoots at them a couple of times. The troops will remain conscious of the good reputation of the German soldier. [51]

Trotha gave orders that captured Herero males were to be executed, while women and children were to be driven into the desert where their death from starvation and thirst was to be certain; Trotha argued that there was no need to make exceptions for Herero women and children, since these would "infect German troops with their diseases", the insurrection Trotha explained "is and remains the beginning of a racial struggle".[39] German soldiers regularly raped young Herero women before killing them or letting them die in the desert[52] After the war, von Trotha argued that his orders were necessary writing in 1909 that "If I had made the small water holes accessible to the womenfolk, I would run the risk of an African catastrophe comparable to the Battle of Beresonia"[53]

The German general staff was aware of the atrocities that were taking place; its official publication, named Der Kampf, noted that:

This bold enterprise shows up in the most brilliant light the ruthless energy of the German command in pursuing their beaten enemy. No pains, no sacrifices were spared in eliminating the last remnants of enemy resistance. Like a wounded beast the enemy was tracked down from one water-hole to the next, until finally he became the victim of his own environment. The arid Omaheke [desert] was to complete what the German army had begun: the extermination of the Herero nation.[54][55]

Alfred von Schlieffen who served as Chief of the Imperial German General Staff approved of von Trotha's intentions in terms of a "racial struggle" and the need to "wipe out the entire nation or to drive them out of the country", but had doubts about his strategy, preferring their surrender.[56]

Governor Leutwein, later relieved of his duties, complained to Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow about Trotha's actions, seeing the general's orders as intruding upon the civilian colonial jurisdiction and ruining any chance of a political settlement.[57] According to Professor Mahmood Mamdani from Columbia University, opposition to the policy of annihilation was largely the consequence of the fact that colonial officials looked at the Herero people as potential source of labor, thus economically important.[58] For instance, Governor Leutwein wrote that:

"I do not concur with those fanatics who want to see the Herero destroyed altogether...I would consider such a move a grave mistake from an economic point of view. We need the Herero as cattle breeders...and especially as labourers.[59]

Having no authority over the military, Chancellor Bülow could only advise Wilhelm II that Trotha's actions were "contrary to Christian and humanitarian principle, economically devastating and damaging to Germany's international reputation."[57]

Upon the arrival of new orders at the end of 1904, prisoners were herded into concentration camps and given by the German state to private companies as slave labourers, and exploited as human guinea pigs in medical experiments[60][61]

Concentration camps

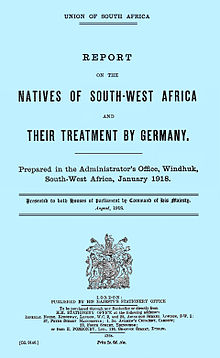

Survivors, majority of whom were women and children, were eventually put in concentration camps, such as that at Shark Island, where the German authorities forced them to work as slave labor for German military and settlers, all prisoners were categorized into groups fit and unfit for work, and pre-printed death certificates indicating "death by exhaustion following privation" were issued.[64] The British government published their well-known account of the German genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples in 1918.[65]

Many Herero died later of disease, overwork and malnutrition.[66][67]

In 1906, Shark Island registered an annual death rate of 227% for the Nama, and 86% for the Herero; other camps, such as Windhoek, showed mortality rates as high as 61%[68] The mortality rate in the camps reached 45% in 1908.[69] The death rates are calculated at between 69 and 74%.[70]

Food in the camps was extremely scarce, consisting of rice with no additions.[71] As the prisoners lacked pots, the rice they received was uncooked and indigestible; horses and oxen that died in the camp were later distributed to the inmates as food.[72] As a result dysentery spread, in addition to lung diseases,[73] despite those conditions the Herero ware taken outside the camp every day for labour under harsh treatment by the German guards, while the sick were left without any medical assistance or nursing care.[73]

Shootings, hangings and beatings were common,[74] and the sjambok was used by guards who treated the forced laborers harshly;[73] a September 28, 1905, article in the South African newspaper Cape Argus detailed some of the abuse, with the heading: "In German S. W. Africa: Further Startling Allegations: Horrible Cruelty". In an interview with Percival Griffith, "an accountant of profession, who owing to hard times, took up on transport work at Angra Pequena, Lüderitz", related his experiences.

"There are hundreds of them, mostly women and children and a few old men ... when they fall they are sjamboked by the soldiers in charge of the gang, with full force, until they get up ... On one occasion I saw a woman carrying a child of under a year old slung at her back, and with a heavy sack of grain on her head ... she fell. The corporal sjamboked her for certainly more than four minutes and sjamboked the baby as well ... the woman struggled slowly to her feet, and went on with her load. She did not utter a sound the whole time, but the baby cried very hard."[75]

During the war, a number of people from the Cape (in modern day South Africa) sought employment as transport riders for German troops in Namibia. Upon their return to the Cape, some of these people recounted their stories, including those of the imprisonment and genocide of the Herero and Namaqua people. Fred Cornell, a British aspirant diamond prospector, was in Lüderitz when the Shark Island extermination camp was being used. Cornell wrote of the camp:

"Cold - for the nights are often bitterly cold there - hunger, thirst, exposure, disease and madness claimed scores of victims every day, and cartloads of their bodies were every day carted over to the back beach, buried in a few inches of sand at low tide, and as the tide came in the bodies went out, food for the sharks."[75]

The extermination camp on Shark Island, in the coastal town of Lüderitz, was the worst of the German South West African camps.[76] Lüderitz lies in southern Namibia, flanked by desert and ocean. In the harbour lies Shark Island, which then was connected to the mainland only by a small causeway. The island is now, as it was then, barren and characterised by solid rock carved into surreal formations by the hard ocean winds. The camp was placed on the far end of the relatively small island, where the prisoners would have suffered complete exposure to the strong winds that sweep Lüderitz for most of the year.

German Commander Von Estorff wrote in a report that approximately 1,700 prisoners had died by April 1907, 1,203 of them Nama. In December 1906, four months after their arrival, 291 Nama died (a rate of more than nine people a day). Missionary reports put the death rate at between 12 and 18 a day; as many as 80% of the prisoners sent to the Shark Island extermination camp never left the island.[75]

There are accusations of Herero women being coerced into sex slavery as a means of survival.[77][78]

Trotha was opposed to contact between natives and settlers, believing that the insurrection was "the beginning of a racial struggle" and fearing that the colonists would be infected by native diseases.[57]

Benjamin Madley argues that it would be more accurate to describe Shark Island not as a concentration camp or work camp, but as an extermination camp or death camp.[79][80][81][82][83]

Medical experiments

Eugen Fischer, a German scientist, came to the concentration camps to conduct medical experiments on race,[78] using children of Herero people and mulatto children of Herero women and German men as test subjects.[78] Together with Theodor Mollison he also experimented upon Herero prisoners[84] Those experiments included sterilization, injection of smallpox, typhus as well as tuberculosis.[69]

The numerous cases of mixed offspring upset the German colonial administration and the obsession with racial purity.[69] Eugen Fischer studied 310 mixed-race children, calling them "Rehoboth bastards" of "lesser racial quality".[69] Fischer also subjected them to numerous racial tests such as head and body measurements, eye and hair examinations. In conclusion of his studies he advocated genocide of alleged "inferior races" stating that "whoever thinks thoroughly the notion of race, can not arrive at a different conclusion".[69]

Fischer's (at the time considered) scientific actions and torment of the children were part of wider history of abusing Africans for experiments, and echoed earlier actions by German anthropologists who stole skeletons and bodies from African graveyards and took them to Europe for research or sale.[69]

An estimated 3000 skulls were sent to Germany for experimentation. In October 2011, after 3 years of talks, the first skulls were due to be returned to Namibia for burial.[85]

Other experiments were made by doctor Bofinger, who injected Herero that were suffering from scurvy with various substances including arsenic and opium, afterwards he researched the effects of these substances by performing autopsies on dead bodies[86]

Number of victims

A census performed in 1905 revealed that 25,000 Herero remained in German South-West Africa.[87]

According to the 1985 United Nations' Whitaker Report, the population of 80,000 Herero was reduced to 15,000 "starving refugees" between 1904 and 1907[88] In Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia by Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes a number of 100,000 victims is given. German author Walter Nuhn states that in 1904 only 40,000 Herero lived in German South-West Africa, and therefore "only 24,000" could have been killed.[9]

Influence upon Nazi Germany

The Herero genocide has commanded the attention of historians who study complex issues of continuity between the Herero Genocide and the Holocaust.[89] It is argued that the Herero genocide set a precedent in Imperial Germany to be later followed by Nazi Germany's establishment of death camps, such as the one at Auschwitz.[90][91]

- According to Benjamin Madley, the German experience in Namibia was a crucial precursor to Nazi colonialism and genocide. He argues that personal connections, literature, and public debates served as conduits for communicating colonialist and genocidal ideas and methods from the colony to Germany.[92]

- Tony Barta, honorary research associate at La Trobe University Melbourne, argues that Herero Genocide was an inspiration for Hitler for his war against Jews.[93]

- According to Clarence Lusane, Eugen Fischer's medical experiments can be seen as testing ground for later medical procedures used during the Nazi Holocaust.[69] Fischer later became chancellor of the University of Berlin, where he taught medicine to Nazi physicians.[78] One of his prominent students was Josef Mengele, the doctor who made genetic experiments on Jewish children at the Auschwitz concentration camp.[94]

- Ben Kiernan, the director of the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University, pointed out that Eugen Fischer was not the only person who took part in both genocides. Franz Ritter von Epp, who was later responsible for liquidation of all Bavarian Jews and Roma as governor of Bavaria, took part in the Herero genocide as well.[95]

- Mahmood Mamdani argues that the links between the Holocaust and the Herero Genocide are beyond the execution of an annihilation policy and the establishment of concentration camps and that there are ideological similarities in the conduct of both genocides. Focusing on a written statement by General Trotha translated as:

I destroy the African tribes with streams of blood... Only following this cleansing can something new emerge, which will remain. [96]

- Mamdani takes note of the similarity between the aims of the General and the Nazis. According to Mamdani in both cases there was a Social Darwinist notion of "cleansing" after which "something new" would "emerge".[78]

Aftermath

With the closure of concentration camps all surviving Herero were distributed as labourers for settlers in the German colony, and from that time on, all Herero's over the age of seven were forced to wear a metal disc with the their labour registration number.,[78] and banned from owning land or cattle, a necessity for pastoral society[97]

About 19,000 German troops were engaged in conflict, of which 3,000 saw combat, the rest were used for upkeep and administration; the German losses were 676 soldiers killed in combat, 76 missing and 689 dead from disease.[98] The costs of the campaign were 600 million marks, the normal subsidy of the colony was usually 14.5 million marks[98] At about the same time, diamonds were discovered in the territory, and this did much to boost its prosperity. However, it was short-lived. In 1915, at the start of World War I, the German colony was taken over and occupied in the South-West Africa Campaign by the Union of South Africa, acting on behalf of the British Imperial Government. South Africa received a League of Nations Mandate over South-West Africa in 1919 under the Treaty of Versailles.

Recognition

In 1985, the United Nations' Whitaker Report classified the massacres as an attempt to exterminate the Herero and Nama peoples of South-West Africa, and therefore one of the earliest cases of genocide in the 20th century[99]

In 1998, German President Roman Herzog visited Namibia and met Herero leaders. Chief Munjuku Nguvauva demanded a public apology and compensation. Herzog expressed regret but stopped short of an apology. He also pointed out that special reparations were out of the question [citation needed].

The Hereros filed a lawsuit in the United States in 2001 demanding reparations from the German government and the Deutsche Bank, which financed the German government and companies in Southern Africa.[100][101]

On August 16, 2004, at the 100th anniversary of the start of the genocide, a member of the German government, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, Germany's Minister for Economic Development and Cooperation, officially apologized and expressed grief about the genocide, declaring in a speech that:

We Germans accept our historical and moral responsibility and the guilt incurred by Germans at that time.[102]

She ruled out paying special compensations, but promised continued economic aid for Namibia which currently amounts to $14m a year.[13]

The von Trotha family travelled to Omaruru in October 2007 by invitation of the royal Herero chiefs and publicly apologized for the actions of their relative. Wolf-Thilo von Trotha said:

We, the von Trotha family, are deeply ashamed of the terrible events that took place 100 years ago. Human rights were grossly abused that time."[103]

Peter Katjavivi, a former Namibian ambassador to Germany, demanded in August 2008 that the skulls of Herero and Nama prisoners of the 1904-08 uprising, which were taken to Germany for scientific research to "prove" the superiority of white Europeans over Africans, be returned to Namibia. Katjavivi was reacting to a German television documentary which reported that its investigators had found over 40 of these skulls at two German universities, among them probably the skull of a Nama chief who had died on Shark Island near Luederitz.[104] In September 2011 the skulls were returned to Namibia.[105]

Revisionism

Brigitte Lau has challenged the analyse of GDR historian Horst Drechsler (Let Us Die Fighting, London, 1988 translation). She considers that his work contains important factual errors, pointing amongst other things to his and other's reliance on First World War British propaganda.[106][verification needed]

Werner Hillebrecht, who criticised Brigitte Lau's work at great length, agrees that there was no plot to commit genocide, and that von Trotha "initially planned to take prisoners". However as the logistical impossibility of dealing with tens of thousands of prisoners became apparent he let the desert deal with the problem. He considers the German high command guilty of genocide because: "They let it happen".[107][verification needed]

It has been pointed out that although German colonists did seize and exploit much Herero/Nama soil, diamonds can't have been a motive as reports of their discovery did not appear until 1908.[108]

Media

A BBC Documentary Namibia - Genocide & the second reich explores the Herero/Nama genocide and the circumstances surrounding it.[109]

Fictional representations

One chapter of Thomas Pynchon's novel V. (1963) is about the Herero genocide. A group of characters of Herero descent are also present in his Gravity's Rainbow (1974), which hints more than once at the Herero massacre.

See also

Original German texts

- ^ translated from German: "Ich kenne genug Stämme in Afrika. Sie gleichen sich alle in dem Gedankengang, dass sie nur der Gewalt weichen. Diese Gewalt mit krassem Terrorismus und selbst mit Grausamkeit auszuüben, war und ist meine Politik. Ich vernichte die aufständischen Stämme mit Strömen von Blut und Geld. Nur auf dieser Aussaat kann etwas Neues entstehen, was Bestand hat" [1]

- ^ translated from German: "Ich, der große General der Deutschen Soldaten, sende diesen Brief an das Volk der Herero. Die Herero sind nicht mehr deutsche Untertanen. Sie haben gemordet und gestohlen, haben verwundeten Soldaten Ohren und Nasen und andere Körperteile abgeschnitten, und wollen jetzt aus Feigheit nicht mehr kämpfen. Ich sage dem Volk: Jeder, der einen der Kapitäne an eine meiner Stationen als Gefangenen abliefert, erhält tausend Mark, wer Samuel Maharero bringt, erhält fünftausend Mark. Das Volk der Herero muss jedoch das Land verlassen. Wenn das Volk dies nicht tut, so werde ich es mit dem Groot Rohr dazu zwingen. Innerhalb der Deutschen Grenzen wird jeder Herero mit und ohne Gewehr, mit oder ohne Vieh erschossen, ich nehme keine Weiber oder Kinder mehr auf, treibe sie zu ihrem Volke zurück, oder lasse auf sie schießen. Dies sind meine Worte an das Volk der Herero. Der große General des mächtigen Deutschen Kaisers.

- Dieser Erlaß ist bei den Appells den Truppen mitzuteilen mit dem Hinzufügen, daß auch der Truppe, die einen der Kapitäne fängt, die entsprechende Belohnung zu teil wird und daß das Schießen auf Weiber und Kinder so zu verstehen ist, daß über sie hinweggeschossen wird, um sie zum Laufen zu zwingen. Ich nehme mit Bestimmtheit an, daß dieser Erlaß dazu führen wird, keine männlichen Gefangenen mehr zu machen, aber nicht zu Grausamkeiten gegen Weiber und Kinder ausartet. Diese werden schon fortlaufen, wenn zweimal über sie hinweggeschossen wird. Die Truppe wird sich des guten Rufes der deutschen Soldaten bewußt bleiben."[48][49]

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (November 2011) |

- ^ Olusoga, David and Erichsen, Casper W (2010). The Kaiser's Holocaust. Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23141-6

- ^

Levi, Neil (2003). The Holocaust: Theoretical Readings. Rutgers University Press. p. 465. ISBN 0813533538.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2001, p. 12

- ^ Allan D. Cooper (2006-08-31). "Reparations for the Herero Genocide: Defining the limits of international litigation". Oxford Journals African Affairs.

- ^ "Remembering the Herero Rebellion". Deutsche Welle. 2004-11-01.

- ^ Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904-1908 (PSI Reports) by Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes

- ^ Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation and Subaltern Resistance in World History (War and Genocide) (War and Genocide) (War and Genocide) A. Dirk Moses -page 296(From Conquest to Genocide: Colonial Rule in German Southwest Africa and German East Africa. 296, (29). Dominik J. Schaller)

- ^ The Imperialist Imagination: German Colonialism and Its Legacy (Social History, Popular Culture, and Politics in Germany) by Sara L. Friedrichsmeyer, Sara Lennox, and Susanne M. Zantop page 87 University of Michigan Press 1999

- ^ a b Walter Nuhn: Sturm über Südwest. Der Hereroaufstand von 1904. Bernhard & Graefe-Verlag, Koblenz 1989. ISBN 3-7637-5852-6.

- ^ Marie-Aude Baronian, Stephan Besser, Yolande Jansen, "Diaspora and memory: figures of displacement in contemporary literature, arts and politics", pg. 33 Rodopi, 2007,

- ^ Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, Israel W. Charny, "Century of genocide: critical essays and eyewitness accounts" pg. 51, Routledge, 2004,

- ^ Dan Kroll, "Securing our water supply: protecting a vulnerable resource", PennWell Corp/University of Michigan Press, pg. 22

- ^ a b "Germany admits Namibia genocide". BBC News. 2004-08-14. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ Herero heroes: a socio-political history of the Herero of Namibia, 1890-1923, Jan-Bart Gewald, Page 31, James Currey 1998

- ^ Peace and freedom, Volume 40, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, page 57, The Section, 1980

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, M. Entry for Maharero". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Marcia Klotz, White women and the dark continent: gender and sexuality in German colonial discourse from the sentimental novel to the fascist film, p. 72: Although records show that Herero leaders repeatedly complained that Germans were raping Herero women and girls with impunity, not a single case of rape came before the colonial courts before the uprising because the Germans looked upon such offenses as mere peccadilloes

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, M. Entry for Samuel Maharero". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ a b “A bloody history: Namibia’s colonisation”, BBC News, August 29, 2001

- ^ Bridgman Jon, The Revolt of the Hereros, pp 19, 34, 50 & 149

- ^ Morel E. D., The Black Man's Burden, pp 55, 64 & 66

- ^ Hull, Isabel V., Absolute destruction: military culture and the practices of war in Imperial Germany, pp 8 & 22.

- ^ Bley, Helmut, Namibia under German rule, pp 10 & 59

- ^ Baranowski, Shelley, Nazi Empire: German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler, pp 47-9, 55-6 & 59

- ^ Steinmetz, George, The devil's handwriting: precoloniality and the German colonial state in pp 147-149, 185-186 & 209

- ^ A. Dirk Moses, Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation and Subaltern Resistance in World History, p. 301

- ^ Bridgman, Jon M. (1981). The revolt of the Hereros. pp. 57 ISBN 9780520041134, California University Press

- ^ a b c Bridgman, p. 60.

- ^ Chalk & Jonassohn, 230.

- ^ Drechsler, Horst. (1980). Let Us Die Fighting. Zed Press. pp. 133.

- ^ Drechsler, p. 132 & 133

- ^ Bridgman, p. 59.

- ^ Dictionary of Genocide: A-L Samuel Totten, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs, page 184, Greenwood 2007

- ^ Bridgman, p. 74

- ^ Wilhelminism and Its Legacies: German Modernities, Imperialism, and the Meanings of Reform, 1890-1930, Geoff Eley and James Retallack, page 171,Berghahn Books,2004

- ^ Bridgman, 56.

- ^ Jon Bridgman, "The revolt of the Hereros" pp. 70 ISBN 9780520041134, University of California Press, 1981

- ^ Clark, p. 604

- ^ a b c Clark, p. 605

- ^ J.B. Gewald, Herero Heroes: A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia 1890 - 1923, Oxford, Cape Town, Athens, OH, 1999, p. 173

- ^ Aparna Rao, The Practice of War: Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed violence, p.91-92 [2]

- ^ Mamdani, p. 11

- ^ a b Century of genocide:critical essays and eyewitness accounts Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons page 22, Routledge 2008

- ^ Drechsler, Let us Die Fighting, p. 157

- ^ Mission, Church and State Relations in South West Africa under German Rule 1884-1915, page 97 Nils Ole Oermann Franz Steiner Verlag 1999

- ^ Mission und Macht im Wandel politischer Orientierungen: Europaische Missionsgesellschaften in politischen Spannungsfeldern in Afrika und Asien zwischen 1800-1945 page 394 Franz Steiner Verlag 2005

- ^ Thomas Tlou,1985, A History of Ngamiland

- ^ Bundesarchiv Potsdam, Akten des Reichskolonialamtes, RKA, 10.01 2089, Bl. 23, Handschriftliche Abschrift der Proklamation an das Volk der Herero und des Zusatzbefehls an die Kaiserliche Schutztruppe, 2. Oktober 1904

- ^ Der Einsatz der Telegraphie im Krieg gegen Afrikaner, p. 195

- ^ Puaux, René The German Colonies; What Is to Become of Them? ISBN 9781113346018

- ^ Hull, Isabel V. Absolute destruction: military culture and the practices of war in Imperial Germany p.56 ISBN 0-8014-7293-8

- ^ Dictionary of Genocide: M-Z Samuel Totten,Paul Robert Bartrop,Steven L. Jacobs page 272 Greenwood 2007

- ^ Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts Samuel Totten,William S. Parsons page 22 Routledge 2008

- ^ Tilman Dedering, A Certain Rigorous Treatment of all Parts of the Nation: The Annihilation of the Herero in German South West Africa, 1904, p. 213

- ^ Bley, 1971: 162

- ^ The Killing Trap: Genocide in the Twentieth Century [Hardcover] Manus I. Midlarsky page 32 Cambridge University Press 2005

- ^ a b c Clark, p. 606

- ^ Mamdani, p.12

- ^ Gewald, Herero Heroes, p. 169

- ^ Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century: The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia, 1904-1908 Jeremy Sarkin page 142, Praeger 2008

- ^ Murderous medicine: Nazi doctors, human experimentation, and Typhus Naomi Baumslag page 37, Praeger 2005

- ^ ‘Stolen’ Blue Book was just misplaced 23.04.2009 accessed 17 Dec 2011

- ^ Gewald, Jan-Bart (1999), Herereo Heroes: A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia 1890-1923, Ohio University Press, p. 242,

"Of late it has been claimed that the infamous 'Blue Book' which detailed the treatment of Africans in GSWA was little more than a piece of propaganda put about to further South Africa's territorial ambitions and Britain's position at the negotiating table. Granted that the book was used to strengthen Britain's position vis-a-vis Germany, it must however be borne in mind that the bulk of the evidence contained in the 'Blue Book' is little more than the literal translation of German texts published at the time which were the findings of a German commission of inquiry into the effects of corporal punishment." Thus, when the Blue Book was withdrawn from the public after Germany and England came to an agreement about how to share access to GSWA minerals, this was not censorship; it was just business

- ^ The colonising camera: photographs in the making of Namibian history Wolfram Hartmann, Jeremy Silvester, Patricia Hayes, page 118, University of Cape Town Press, 1999

- ^ Jan-Bart Gewald, Jeremy Silvester, "Words Cannot Be Found: German Colonial Rule in Namibia : An Annotated Reprint of the 1918 Blue Book (Sources on African History, 1)", Brill Academic Publishers, annotated edition (June 1, 2003)

- ^ Michael Mann (2004), The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing, Cambridge University Press, p. 105

- ^ Hitler's African Victims: The German Army Massacres of Black French Soldiers in 1940, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 83

- ^ Helmut Walser Smith (2008), The continuities of German history: nation, religion, and race across the Long Nineteenth Century, Cambridge University Press, p. 199

- ^ a b c d e f g Hitler's Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of European Blacks, Africans and African Americans During the Nazi Era (Crosscurrents in African American History) by Clarence Lusane, page 50-51 Routledge 2002

- ^ Steinmetz, George, The devil's handwriting, pp 196-216

- ^ The practice of war Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed Violence Edited by Aparna Rao, Michael Bollig and Monika Böck, page 92, Berghahn Books; 2011

- ^ Hull 75

- ^ a b c Hull 76

- ^ Klaas van Walraven (2003), Rethinking resistance: revolt and violence in African history, Brill Academic Publishers, p. 282

- ^ a b c News Monitor for September 2001 Prevent Genocide International

- ^ The scramble for Africa, 1876-1912 Thomas Pakenham, page 615, Random House, 1991

- ^ "The tribe Germany wants to forget", Mail & Guardian, March 13, 1998,

through raceandhistory.com

- ^ a b c d e f Mamdani, p. 12

- ^ Benjamin Madley, "From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe", European History Quarterly 2005 35: 429: "Operational from 1905 to 1907, Haifischinsel, or Shark Island, was the twentieth century’s first death camp. Though referred to as a Konzentrationslager in Reichstag debates, it functioned as an extermination center."

- ^ op cit., p. 446: "Colonial Namibia’s death camp at Shark Island was different from Spanish and British concentration camps in that it was operated for the purpose of destroying human life. Thus, it served as a rough model for later Nazi Vernichtungslager, or annihilation camps, like Treblinka and Auschwitz, whose primary purpose was murder."

- ^ op cit., p. 432: "General von Trotha’s explicit, October 1904 Vernichtungsbefehl had created a backlash of protest in Germany that led to the order’s termination in December 1904, and to von Trotha’s transfer to Germany in November 1905."

- ^ op cit., p. 429: "Commanding officer General Lothar von Trotha then launched an explicit genocide program against the defeated nation, announcing: ‘I will annihilate the rebelling tribes with rivers of blood and rivers of gold. Only after a complete uprooting will something new emerge.’"

- ^ "Absolute Destruction: Military, Culture And the Practices of War in Imperial Germany", Isabel V. Hull, Cornell University Press, 2006; see footnote #64, pp. 81-82:"'Sterblichkeit in den Kriegsgefangenlargern,' Nr. KA II.1181, copy of undated report compiled by the Schutztruppe Command, read in Col. Dept. 24 Mar. 1908, BA-Berlin, R 1001. Nr. 2040, pp. 161-62. The other annual average death rates (for the period Oct. 1904 to Mar. 1907) were as follows: Okahandja, 37.2%; Windhuk, 50.4%; Swakopmund, 74%; Shark Island in Lüderitzbucht, 121.2% for Nama, 30% for Herero. Traugott Tjienda, headsman of the Herero at Tsumbe and foreman of a large group of prisoners at the Otavi lines for two years, testified years later to a death rate of 28% (148 dead of 528 laborers) in his unit, Union of South Africa, 'Report on the Natives', 101." In this excerpt, "BA-Berlin" means Bundesarchiv (Berlin-Lichterfelde); "Lüderitzbucht" means Lüderitz Bay; Tsumbe was a copper mine; Otavi was the railroad that the inmates of Shark Island were forced to build.

- ^ The Geography of Genocide Allan D. Cooper page 153 University Press of America 2008

- ^ http://www.timeslive.co.za/scitech/2011/09/27/germans-return-skulls-to-namibia

- ^ The Kaiser's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism,page 225,Casper Erichsen, David Olusoga, Faber and Faber 2010

- ^ Frank Robert Chalk, Kurt Jonassohn, Institut montréalais des études sur le génocide, "The history and sociology of genocide" pg. 246, Yale University Press, 1990 ISBN 9780300044461

- ^ UN Whitaker Report on Genocide, 1985, paragraphs 14 to 24, pages 5 to 10 Prevent Genocide International

- ^ A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures - Continental Europe and its Empires, page 240 Edinburgh University Press 2009

- ^ Andrew Zimmerman, "Anthropology and antihumanism in Imperial Germany", University of Chicago Press, 2001, pg. 244

- ^ "Imperialism and Genocide in Namibia". Socialist Action. 1999.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Benjamin Madley, "From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe," European History Quarterly 2005 35(3): 429-464

- ^ Identity Politics in the Age of Genocide The Holocaust and Historical Representation, page 97, David B. MacDonald, 2007 Routledge

- ^ Jere-Malanda, "The Tribe Germany Wants to Forget", p. 20

- ^ Blood and Soil, A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfurt, Ben Kiernan, page 36 2007, Yale University Press

- ^ Gewald, Herero Heroes, p. 174

- ^ Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed Violence Aparna Rao, Michael Bollig and Monika Böck,page 89, Berghahn Books 2008

- ^ a b Hull 88

- ^ Encyclopedia of genocide Desmond Tutu, Simon Wiesenthal, Israel W. Charny, page 288-289, ABC-CLIO 1999

- ^ "Germany regrets Namibia 'genocide'". BBC News. 2004-01-12.

- ^ "German bank accused of genocide". BBC News. 2001-09-25.

- ^ "Speech at the commemorations of the 100th anniversary of the suppression of the Herero uprising, Okakarara, Namibia, 14 August 2004". Deutsche Botshaft Windhuk/German Embassy in Windhuk. 2004-08-14.

- ^ "German family's Namibia apology". BBC News. 2007-10-07.

- ^ Katjavivi demands Herero skulls from Germany, The Namibian, 24 July 2008

- ^ "Germany returns Namibian skulls". BBC News. 2011-10-30.

- ^ Lau, Brigitte (April 1989), "Uncertain Certainties: The Herero-German War of 1904", Migabus, 2: 4–8

- ^ Werner, Hillebrecht (April 2007), "Certain Uncertainties", Journal of Namibian Studies, 1: 73–95

- ^ Chalk, Frank; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990) The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Yale University Press. pp. 230.

- ^ “Namibia - Genocide and the second Reich”BBC

Bibliography and documentaries

- Rachel Anderson, Redressing Colonial Genocide Under International Law: The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany, 93 California Law Review 1155 (2005).

- Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600–1947. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard. p. 776. ISBN 067402385-4.

- Exterminate all the Brutes, Sven Lindqvist, London, 1996.

- "A Forgotten History-Concentration Camps were used by Germans in South West Africa", Casper W. Erichsen, in the Mail and Guardian, Johannesburg, 17 August 2001.

- Genocide & The Second Reich, BBC Four, David Olusoga, October 2004

- German Federal Archives, Imperial Colonial Office, Vol. 2089, 7 (recto)

- "The Herero and Nama Genocides, 1904-1908", J.B. Gewald, in Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, New York, Macmillan Reference, 2004.

- Herero Heroes: A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia 1890 - 1923, J.B. Gewald, Oxford, Cape Town, Athens, OH, 1999.

- Let Us Die Fighting: the Struggle of the Herero and Nama against German Imperialism, 1884-1915, Horst Drechsler, London, 1980.

- "The Revolt of the Hereros", Jon M. Bridgman, Perspectives on Southern Africa, Berkeley, University of California, 1981.

- A probable source for much of this information is Isabell Hull's Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005). Parts of this entry are nearly word-for-word summaries of Hull's analysis.

- Hull, Isabell (2005) "The Military Campaign in German Southwest Africa, 1904-1907. Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Issue 37, pp. 39-49.

- Zimmerer, Jürgen (2005) "Annihilation in Africa: The 'Race War' in German Southwest Africa (1904-1908) and its Significance for a Global History of Genocide." Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Issue 37, pp. 51–57.

- Absolute Destruction: Military Culture And the Practices of War in Imperial Germany by Isabel V. Hull Cornell University Press 2006

- Mohamed Adhikari, "'Streams Of Blood And Streams Of Money': New Perspectives on the Annihilation of the Herero and Nama Peoples Of Namibia, 1904-1908," Kronos: Journal Of Cape History 2008 34: 303-320