Variable-frequency drive

A variable-frequency drive (VFD) is a power electronics conversion device used in an electro-mechanical drive system that controls the AC motor's speed and torque output by varying the electrical motor input's frequency and voltage.[1][2][3][4] A special type in the adjustable-speed class of drives, variable-frequency drives are also known as adjustable-frequency drives (AFD), variable-speed drives (VSD), AC drives, micro drives or inverter drives.

While use of variable-frequency drives is widespread in breadth, applications ranging from small appliances to the largest of mine mill drives and compressors, the majority of the world's electric motors are used in fixed-speed centrifugal pump, fan and compressor applications and AC drives' global penetration of the motor market is still relatively small. This presents attractive opportunities for application of AC drives in both retrofitted and new installations, drives being destined to play a dominant role in solving global climate warming problems through energy savings.[5]

Power electronics technology has over the last four decades resulted in truly remarkable AC drive cost and size reduction and performance improvements due to the convergence of advancements in drives' semiconductor switching devices, drive topologies, simulation and control techniques, and control hardware and software.[5][6]

System description and operation

A variable frequency drive is a device used in a drive system consisting of the following three main sub-systems: AC motor, main drive controller assembly, and drive operator interface.[7][4]

Motor

The motor used in a VFD system is usually a three-phase induction motor. Some types of single-phase motors can be used, but three-phase motors are usually preferred. Various types of synchronous motors offer advantages in some situations, but induction motors are suitable for most purposes and are generally the most economical choice. Motors that are designed for fixed-speed operation are often used. Elevated voltage stresses imposed on induction motors that are supplied by VFDs require that such motors be designed for definite-purpose inverter-fed duty in accordance to such requirements as Part 31 of NEMA Standard MG-1.[8]

Controller

The variable frequency drive controller is a solid state power electronics conversion system consisting of three distinct sub-systems: a rectifier bridge converter, a direct current (DC) link, and an inverter. Variable-source inverter (VSI) drives (see 'Generic topologies' sub-section below) are by far the most common type of drives. Most drives are AC-AC drives in that they convert AC line input to AC inverter output. However, in some applications such as common DC bus or solar applications, drives are configured as DC-AC drives. The most basic rectifier converter for the VSI drive is configured as a three-phase, six-pulse, full-wave diode bridge. In a VSI drive, the DC link consists of a capacitor which smooths out the converter's DC output ripple and provides a stiff input to the inverter. This filtered DC voltage is converted to quasi-sinusoidal AC voltage output using the inverter's active switching elements. VSI drives provide higher power factor and lower harmonic distortion than phase-controlled current-source inverter (CSI) and load-commutated inverter (LCI) drives (see 'Generic topologies' sub-section below). The drive controller can also be configured as a phase converter having single-phase converter input and three-phase inverter output.[9]

Controllers have evolved to exploit quantum solid state power switching device improvements in terms of voltage and current ratings and switching frequency over the past six decades. Introduced in the 1983,[10] the insulated-gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) has in the past two decades come to dominate VFDs as an inverter switching device.[11][12][13]

In variable-torque applications suited for Volts per Hertz (V/Hz) drive control, AC motor characteristics require that the voltage magnitude of the inverter's output to the motor be adjusted to match the required load torque in a linear V/Hz relationship. For example, for 460 volt, 60 Hz motors this linear V/Hz relationship is 460/60 = 7.67 V/Hz. While suitable in wide ranging applications, V/Hz control is sub-optimal in high performance applications involving low speed or demanding, dynamic speed regulation, positioning and reversing load requirements. Some V/Hz control drives can also operate in quadratic V/Hz mode or can even be programmed to suit special multi-point V/Hz paths.[14][15]

The two other drive control platforms, vector control and direct torque control (DTC), adjust the motor voltage magnitude, angle from reference and frequency[16] such as to precisely control the motor's magnetic flux and mechanical torque.

Although space vector pulse-width modulation (SVPWM) is becoming increasingly popular,[17] sinusoidal PWM (SPWM) is the most straightforward method used to vary drives' motor voltage (or current) and frequency. With SPWM control (see Fig. 1), quasi-sinusoidal, variable-pulse-width output is constructed from intersections of a saw-toothed carrier frequency signal with a modulating sinusoidal signal which is variable in operating frequency as well as in voltage (or current).[18][11][19]

Operation of the motors above rated nameplate speed (base speed) is possible, but is limited to conditions that do not require more power than the nameplate rating of the motor. This is sometimes called "field weakening" and, for AC motors, means operating at less than rated V/Hz and above rated nameplate speed. Permanent magnet synchronous motors have quite limited field weakening speed range due to the constant magnet flux linkage. Wound rotor synchronous motors and induction motors have much wider speed range. For example, a 100 hp, 460 V, 60 Hz, 1775 RPM (4 pole) induction motor supplied with 460 V, 75 Hz (6.134 V/Hz), would be limited to 60/75 = 80% torque at 125% speed (2218.75 RPM) = 100% power.[20] At higher speeds the induction motor torque has to be limited further due to the lowering of the breakaway torque of the motor. Thus rated power can be typically produced only up to 130...150% of the rated nameplate speed. Wound rotor synchronous motors can be run at even higher speeds. In rolling mill drives often 200...300% of the base speed is used. The mechanical strength of the rotor limit the maximum speed of the motor.

An embedded microprocessor governs the overall operation of the VFD controller. Basic programming of the microprocessor is provided as user inaccessible firmware. User programming of display, variable and function block parameters is provided to control, protect and monitor the VFD, motor and driven equipment.[11][21]

The basic drive controller can be configured to selectively include such optional power components and accessories as follows:

- Connected upstream of converter - circuit breaker or fuses, isolation contactor, EMC filter, line reactor, passive filter

- Connected to DC link - braking chopper, braking resistor

- Connected downstream of inverter - output reactor, sine wave filter, dV/dt filter.[a][23]

Operator interface

The operator interface provides a means for an operator to start and stop the motor and adjust the operating speed. Additional operator control functions might include reversing, and switching between manual speed adjustment and automatic control from an external process control signal. The operator interface often includes an alphanumeric display and/or indication lights and meters to provide information about the operation of the drive. An operator interface keypad and display unit is often provided on the front of the VFD controller as shown in the photograph above. The keypad display can often be cable-connected and mounted a short distance from the VFD controller. Most are also provided with input and output (I/O) terminals for connecting pushbuttons, switches and other operator interface devices or control signals. A serial communications port is also often available to allow the VFD to be configured, adjusted, monitored and controlled using a computer.[11][24][25]

Drive operation

Referring to the accompanying chart, drive applications can be categorized as single-quadrant, two-quadrant or four-quadrant; the chart's four quadrants are defined as follows:[26][27][28]

- Quadrant I - Motoring or driving, forward accelerating quadrant with positive speed and torque

- Quadrant II - Generating or braking, forward braking-decelerating quadrant with positive speed and negative torque

- Quadrant III - Motoring or driving, reverse accelerating quadrant with negative speed and torque

- Quadrant IV - Generating or braking, reverse braking-decelerating quadrant with negative speed and positive torque.

Most applications involve single-quadrant loads operating in quadrant I, such as in variable-torque (e.g. centrifugal pumps or fans) and certain constant-torque (e.g. extruders) loads.

Certain applications involve two-quadrant loads operating in quadrant I and II where the speed is positive but the torque changes polarity as in case of a fan decelerating faster than natural mechanical losses. Some sources define two-quadrant drives as loads operating in quadrants I and III where the speed and torque is same (positive or negative) polarity in both directions.

Certain high-performance applications involve four-quadrant loads (Quadrants I to IV) where the speed and torque can be in any direction such as in hoists, elevators and hilly conveyors. Regeneration can only occur in the drive's DC link bus when inverter voltage is smaller in magnitude than the motor back-EMF and inverter voltage and back-EMF are the same polarity.[29]

In starting a motor, a VFD initially applies a low frequency and voltage, thus avoiding high inrush current associated with direct on line starting. After the start of the VFD, the applied frequency and voltage are increased at a controlled rate or ramped up to accelerate the load. This starting method typically allows a motor to develop 150% of its rated torque while the VFD is drawing less than 50% of its rated current from the mains in the low speed range. A VFD can be adjusted to produce a steady 150% starting torque from standstill right up to full speed.[30] However, cooling of the motor deteriorates as speed decreases such that low speed motor operation with significant torque for long periods is not usually possible due to overheating without addition of external fan.

With a VFD, the stopping sequence is just the opposite as the starting sequence. The frequency and voltage applied to the motor are ramped down at a controlled rate. When the frequency approaches zero, the motor is shut off. A small amount of braking torque is available to help decelerate the load a little faster than it would stop if the motor were simply switched off and allowed to coast. Additional braking torque can be obtained by adding a braking circuit (resistor controlled by a transistor) to dissipate the braking energy. With a four-quadrant rectifier (active-front-end), the VFD is able to brake the load by applying a reverse torque and injecting the energy back to the AC line.

Benefits

Energy savings

Many fixed-speed motor load applications that are supplied direct from AC line power can save energy when they are operated at variable-speed, by means of VFD. Such energy cost savings are especially pronounced in variable-torque centrifugal fan and pump applications, where the loads' torque and power vary with the square and cube, respectively, of the speed. This change gives a large power reduction compared to fixed-speed operation for a relatively small reduction in speed. For example, at 63% speed a motor load consumes only 25% of its full speed power. This is in accordance with affinity laws that define the relationship between various centrifugal load variables.

In the United States, an estimated 60-65% of electrical energy is used to supply motors, 75% of which are variable torque fan, pump and compressor loads. [31] Eighteen percent of the energy used in the 40 million motors in the U.S. could be saved by efficient energy improvement technologies such as VFDs.[32] Only about 3% of the total installed base of AC motors are provided with AC drives.[33] However, it is estimated that drive technology is adopted in as many as 30-40% of all newly installed motors.[34]

An energy consumption breakdown of the global population of AC motor installations is as shown in the following table:

| Small | General Purpose - Medium-Size | Large | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power | 10W to 750W | 750W to 375kW | 375kW to 100MW |

| Phase, voltage | 1-ph., <240V | 3-ph., 200V to 1kV | 3-ph., 1kV to 20kV |

| % total motor energy | 9% | 68% | 23% |

| Total stock | 2 billion | 230 million | 0.6 million |

Control performance

AC drives are used to bring about process and quality improvements in industrial and commercial applications' acceleration, flow, monitoring, pressure, speed, temperature, tension and torque.[36]

Fixed-speed operated loads subject the motor to a high starting torque and to current surges that are up to eight times the full-load current. AC drives instead gradually ramp the motor up to operating speed to lessen mechanical and electrical stress, reducing maintenance and repair costs, and extending the life of the motor and the driven equipment.

Variable speed drives can also run a motor in specialized patterns to further minimize mechanical and electrical stress. For example, an S-curve pattern can be applied to a conveyor application for smoother deceleration and acceleration control, which reduces the backlash that can occur when a conveyor is accelerating or decelerating.

Performance factors tending to favor use of DC, over AC, drives include such requirements as continuous operation at low speed, four-quadrant operation with regeneration, frequent acceleration and deceleration routines, and need for motor to be protected for hazardous area.[37] The following table compares AC and DC drives according to certain key parameters:[38][39]

| Drive type | DC | VFD | VFD | VFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Brush Type DC | AC V/Hz Control | AC Open-Loop Vector | AC Closed-Loop Flux Vector |

| Typical speed regulation (%) | 0.01 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Typical speed range at constant torque (%)) | 0-100 | 10-100 | 3-100 | 0-100 |

| Min. speed at 100% torque (% of base) | Standstill | 8% | 2% | Standstill |

| Multiple-motor operation recommended | No | Yes | No | No |

| Fault protection (Fused only or inherent to drive) | Fused only | Inherent | Inherent | Inherent |

| Maintenance | (Brushes) | Low | Low | Low |

| Feedback device | Tachometer or encoder | N/A | N/A | Encoder |

VFD types and ratings

Generic topologies

A topology being defined in power electonics parlance as simply showing the relationship between AC drives' various elements, AC drives can be classified according to the following generic topologies:[40][41]

- Voltage-source inverter (VSI) drive topologies (see image): In a VSI drive, the DC output of the diode-bridge converter stores energy in the capacitor bus to supply stiff voltage input to the inverter. The vast majority of drives are VSI type with PWM voltage output.

- Current-source inverter (CSI) drive topologies (see image): In a CSI drive, the DC output of the SCR-bridge converter stores energy in series-reactor connection to supply stiff current input to the inverter. CSI drives can be operated with either PWM or six-step waveform output.

- Six-step inverter drive topologies (see image):[42] Now largely obsolete, six-step drives can be either VSI or CSI type and are also referred to as variable-voltage inverter drives, pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) drives,[43] square-wave drives or D.C. chopper inverter drives.[44] In a six-step drive, the DC output of the SCR-bridge converter is smoothed via capacitor bus and series-reactor connection to supply via Darlington Pair or IGBT inverter quasi-sinusoidal, six-step voltage or current input to an induction motor.[45]

- Load commutated inverter (LCI) drive topologies: In a LCI drive, a special CSI case, the DC output of the SCR-bridge converter stores energy via DC link inductor circuit to supply stiff quasi-sinusoidal six-step current output of a second SCR-bridge's inverter and an over-excited synchronous machine.

- Cycloconverter or matrix converter (MC) topologies (see image): Cycloconverter and MC are AC/AC converters that have no intermediate DC link for energy storage. A cycloconverter operates as a three-phase current source via three anti-parallel connected SCR-bridges in six-pulse configuration, each cycloconverter phase acting selectively to convert fixed line frequency AC voltage to an alternating voltage at a variable load frequency. MC drives are IGBT-based.

- Doubly fed slip[b] recovery system topologies: A doubly fed slip recovery system feeds rectified slip power to a smoothing reactor to supply power to the AC supply network via an inverter, the speed of the motor being controlled by adjusting the DC current.

Control platforms

Most drives use one or more of the following control platforms:[40][46]

- PWM V/Hz scalar control

- PWM field-oriented control (FOC) or vector control

- Direct torque control (DTC).

Load torque and power characteristics

Variable frequency drives are also categorized by the following load torque and power characteristics:

- Variable torque, such as in centrifugal fan, pump and blower applications

- Constant torque, such as in conveyor and displacement pump applications

- Constant power, such as in machine tool and traction applications.

Available power ratings

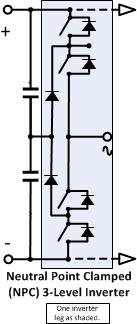

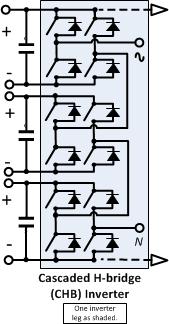

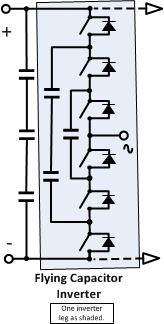

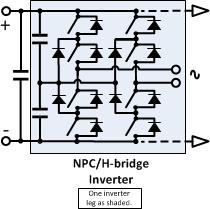

VFDs are available with voltage and current ratings covering a wide range of single-phase and multi-phase AC motors. Low voltage (LV) drives are designed to operate at output voltages equal to or less than 690 V. While motor-application LV drives are available in ratings of up to the order of 5 or 6 MW,[47] economic considerations typically favor medium voltage (MV) drives with much lower power ratings. Different MV drive topologies (see Table 2) are configured in accordance with the voltage/current-combination ratings used in different drive controllers' switching devices[48] such that any given voltage rating is greater than or equal to one to the following standard nominal motor voltage ratings: generally either 2.3/4.16 kV (60 Hz) or 3.3/6.6 kV (50 Hz), with one thyristor manufacturer rated for up to 12 kV switching. In some applications a step up transformer is placed between a LV drive and a MV motor load. MV drives are typically rated for motor applications greater than between about 375 kW (500 hp) and 750 kW (1000 hp). MV drives have historically required considerably more application design effort than required for LV drive applications.[49][50] The power rating of MV drives can reach 100 MW, a range of different drive topologies being involved for different rating, performance, power quality and reliability requirements.[51][52][53]

Drives by machines & detailed topologies

It is lastly useful to relate VFDs in terms of the following two classifications:

- In terms of various AC machines as shown in Table 1 below[54][55]

- In terms of various detailed AC-AC converter topologies shown in Tables 2 and 3 below.[56][53][52][41][40][57][58][59]

Table 1: Drives by machines

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 2: Drives by detailed AC-AC converter topologies

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Legend for Tables 1 to 3

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Application considerations

AC line harmonics

Note of clarification:.[c]

While harmonics in the PWM output can easily be filtered by carrier frequency related filter inductance to supply near-sinusoidal currents to the motor load,[60] the VFD's diode-bridge rectifier converts AC line voltage to DC voltage output by super-imposing non-linear half-phase current pulses thus creating harmonic current distortion, and hence voltage distortion, of the AC line input. When the VFD loads are relatively small in comparison to the large, stiff power system available from the electric power company, the effects of VFD harmonic distortion of the AC grid can often be within acceptable limits. Furthermore, in low voltage networks, harmonics caused by single phase equipment such as computers and TVs are partially cancelled by three-phase diode bridge harmonics because their 5th and 7th harmonics are in counterphase.[61] However, when the proportion of VFD and other non-linear load compared to total load or of non-linear load compared to the stiffness at the AC power supply, or both, is relatively large enough, the load can have a negative impact on the AC power waveform available to other power company customers in the same grid.

When the power company's voltage becomes distorted due to harmonics, losses in other loads such as normal fixed-speed AC motors are increased. This may lead to overheating and shorter operating life. Also substation transformers and compensation capacitors are affected negatively. In particular, capacitors can cause resonance conditions that can unacceptably magnify harmonic levels. In order to limit the voltage distortion, owners of VFD load may be required to install filtering equipment to reduce harmonic distortion below acceptable limits. Alternatively, the utility may adopt a solution by installing filtering equipment of its own at substations affected by the large amount of VFD equipment being used. In high power installations harmonic distortion can be reduced by supplying multi-pulse rectifier-bridge VFDs from transformers with multiple phase-shifted windings.[62]

It is also possible to replace the standard diode-bridge rectifier with a bi-directional IGBT switching device bridge mirroring the standard inverter which uses IGBT switching device output to the motor. Such rectifiers are referred to by various designations including active infeed converter (AIC), active rectifier, IGBT supply unit (ISU), active front end (AFE) or four-quadrant operation. With PWM control and suitable input reactor, AFE's AC line current waveform can be nearly sinusoidal. AFE inherently regenerates energy in four-quadrant mode from the DC side to the AC grid. Thus no braking resistor is needed and the efficiency of the drive is improved if the drive is frequently required to brake the motor.

Two other harmonics mitigation techniques exploit use of passive or active filters connected to a common bus with at least one VFD branch load on the bus. Passive filters involve the design of one or more low-pass LC filter traps, each trap being tuned as required to a harmonic frequency (5th, 7th, 11th, 13th, . . . kq+/-1, where k=integer, q=pulse number of converter).[63]

It is very common practice for power companies or their customers to impose harmonic distortion limits based on IEC or IEEE standards. For example, IEEE Standard 519 limits at the customer's connection point call for the maximum individual frequency voltage harmonic to be no more than 3% of the fundamental and call for the voltage total harmonic distortion (THD) to be no more than 5% for a general AC power supply system. [64]

Long lead effects

The carrier frequency pulsed output voltage of a PWM VFD causes rapid rise times in these pulses, the transmission line effects of which must be considered. Since the transmission-line impedance of the cable and motor are different, pulses tend to reflect back from the motor terminals into the cable. The resulting voltages can produce overvoltages equal to twice the DC bus voltage or up to 3.1 times the rated line voltage for long cable runs, putting high stress on the cable and motor windings and eventual insulation failure. Note that standards for three-phase motors rated 230 V or less adequately protect against such long lead overvoltages. On 460 or 575 V systems and inverters with 3rd generation 0.1 microsecond rise time IGBTs, the maximum recommended cable distance between VFD and motor is about 50 m or 150 feet. Solutions to overvoltages caused by long lead lengths include minimizing cable distance, lowering carrier frequency, installing dV/dt filters, using inverter duty rated motors (that are rated 600 V to withstand pulse trains with rise time less than or equal to 0.1 microsecond, of 1,600 V peak magnitude), and installing LCR low-pass sine wave filters.[69][70][71] Regarding lowering of carrier frequency, note that audible noise is noticeably increased for carrier frequencies less than about 6 kHz and is most noticeable at about 3 kHz. Note also that selection of optimum PWM carrier frequency for AC drives involves balancing noise, heat, motor insulation stress, common mode voltage induced motor bearing current damage, smooth motor operation, and other factors. Further harmonics attenuation can be obtained by using an LCR low-pass sine wave filter or dV/dt filter.

Motor bearing currents

PWM drives are inherently associated with high frequency common mode voltages and currents which may cause trouble with motor bearings.[72] When these high frequency voltages find a path to earth through a bearing, transfer of metal or electrical discharge machining (EDM) sparking occurs between the bearing's ball and the bearing's race. Over time EDM-based sparking causes erosion in the bearing race that can be seen as a fluting pattern. In large motors, the stray capacitance of the windings provides paths for high frequency currents that pass through the motor shaft ends, leading to a circulating type of bearing current. Poor grounding of motor stators can lead to shaft ground bearing currents. Small motors with poorly grounded driven equipment are susceptible to high frequency bearing currents.[73]

Prevention of high frequency bearing current damage uses three approaches: good cabling and grounding practices, interruption of bearing currents, and filtering or damping of common mode currents. Good cabling and grounding practices can include use of shielded, symmetrical-geometry power cable to supply the motor, installation of shaft grounding brushes, and conductive bearing grease. Bearing currents can be interrupted by installation of insulated bearings and specially designed electrostatic shielded induction motors. Filtering and damping high frequency bearing, or, instead of using standard 2-level inverter drives, using either 3-level inverter drives or matrix converters.[74][73]

Since inverter-fed motor cables' high frequency current spikes can interfere with other cabling in facilities, such inverter-fed motor cables should not only be of shielded, symmetrical-geometry design but should also be routed at least 50 cm away from signal cables.[75]

Dynamic braking

Torque generated by the drive causes the induction motor to run at synchronous speed less the slip. If load inertia energy is greater that the energy delivered to the motor shaft, motor speed decreases as negative torque is developed in the motor and the motor acts as a generator, converting output shaft mechanical power back to electrical energy. This power is returned to the drive's DC link element (capacitor or reactor). A DC-link-connected electronic power switch or braking DC chopper (either built-in or external to the drive) transfers this energy to external resistors to dissipate the energy as heat. Cooling fans may be used to prevent resistor overheating.[76]

Dynamic braking wastes braking energy by transforming it to heat. By contrast, regenerative drives recover braking energy by injecting this energy on the AC line. The capital cost of regenerative drives is however relatively high.[77]

Regenerative drives

Regenerative AC drives have the capacity to recover the braking energy of a load moving faster than the designated motor speed (an overhauling load) and return it to the power system.

Cycloconverter, Scherbius, matrix, CSI and LCI drives inherently allow return of energy from the load to the line, while voltage-source inverters require an additional converter to return energy to the supply.[78][79]

Regeneration is only useful in variable-frequency drives where the value of the recovered energy is large compared to the extra cost of a regenerative system,[78] and if the system requires frequent braking and starting. An example would be conveyor belt drives for manufacturing, which stop every few minutes. While stopped, parts are assembled correctly; once that is done, the belt moves on. Another example is a crane, where the hoist motor stops and reverses frequently, and braking is required to slow the load during lowering. Regenerative variable-frequency drives are widely used where speed control of overhauling loads is required.[2][3][80]

See also

Notes

- ^ The mathematical symbol dV/dt, defined as the derivative of voltage V with time t, provides a measure of rate of voltage rise, the maximum admissible value of which expresses the capability of capacitors, motors and other affected circuit elements to withstand high current or voltage spikes due to fast voltage changes; dV/dt is usually expressed in V/microsecond.[22]

- ^ As described in induction motor.

- ^ The harmonics treatment that follows is limited for simplication reasons to LV VSI-PWM drives.

References

- ^ Campbell, Sylvester J. (1987). Solid-State AC Motor Controls. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. pp. 79–189. ISBN 0-8247-7728-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Jaeschke, Ralph L. (1978). Controlling Power Transmission Systems. Cleveland, OH: Penton/IPC. pp. 210–215.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Jaeschke" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Siskind, Charles S. (1963). Electrical Control Systems in Industry. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. p. 224. ISBN 0-07-057746-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Siskind" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b NEMA Standards Publication (2007). Application Guide for AC Adjustable Speed Drive Systems. Rosslyn, VA USA: National Electrical Manufacturers Association (now The Association of Electrical Equipment and Medical Imaging Manufacturers). p. 4. Retrieved Mar. 27, 2008.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Bose, B. K. (2009). "Power Electronics and Motor Drives Recent Progress and Perspective". IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 56 (2): 581–588.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yano, Masao; et al. "History of Power Electronics for Motor Drives in Japan" (PDF). Retrieved 18 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Jaeschke, pp. 210-211

- ^ NEMA Guide, p. 13

- ^ Campbell, pp. 79-83

- ^ Bose, Bimal K. (2006). Power Electronics and Motor Drives : Advances and Trends. Amsterdam: Academic. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-12-088405-6.

- ^ a b c d Bartos, Frank J. (Sep. 1, 2004). "AC Drives Stay Vital for the 21st Century". Control Engineering. Reed Business Information.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Eisenbrown, Robert E. (May 18, 2008). "AC Drives, Historical and Future Perspective of Innovation and Growth". Keynote Presentation for the 25th Anniversary of The Wisconsin Electric Machines and Power Electronics Consortium (WEMPEC). University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA: WEMPEC. pp. 6–10.

{{cite conference}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Jahn, Thomas M. (Jan. 2001). "AC Adjustable-Speed Drives at the Millennium: How Did We Get Here?". IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics. 16 (1). IEEE: 17–25. doi:10.1109/63.903985.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Basics of AC drives". p. Hardware-Part 2: slide 2 of 9. Retrieved Apr. 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bose, Bimal K. (1980). Adjustable Speed AC Drive Systems. New York: IEEE Press. ISBN 0-87942-146-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Yano, p. 13

- ^ Bose, Bimal K. (2011). "Energy Scenario and Impact on Power Electronics In the 21st Century" (PDF). Doha,Qatar. p. 12. Retrieved Feb.8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (help) - ^ Bose (2006), p. 183

- ^ Campbell, pp. 82–85

- ^ Bose (1980), p. 3

- ^ Basics of AC Drives, p. Programming: slide 3 of 7

- ^ "Film capacitors - Short Definition of Terms" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Basics of AC Drives, p. Hardware - Part 2: slide 7 of 9

- ^ Cleaveland, Peter (Nov. 1, 2007). "AC Adjustable Speed Drives". Control Engineering. Reed Business Information.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Campbell, pp. 107-129

- ^ "Technical guide No. 8 - Electrical Braking" (PDF). Retrieved Apr. 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Energy Regeneration" (PDF). Retrieved Apr. 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Basics of AC Drives, pp. Hardware - Part 1: slides 9-10 of 11

- ^ Energy Regeneration, slide 6

- ^ Campbell, pp. 95-102

- ^ Bose, Bimal K. (June 2009). "The Past, Present, and Future of Power Electronics". Industrial Electronics Magazine, IEEE. 3 (2): 9. doi:10.1109/MIE.2009.932709.

- ^ Spear, Mike. "Adjustable Speed Drives: Drive Up Energy Efficiency". ChemicalProcessing.com. Retrieved Jan. 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Guide to Variable Speed Drives - Technical Guide No. 4" (PDF). Retrieved Jan. 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Lendenmann, Heinz; et al. "Motoring Ahead" (PDF). Retrieved Apr. 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Waide, Paul (2011). "Energy-Efficiency Policy Opportunities for Electric Motor-Driven Systems" (PDF). International Energy Agency. Retrieved Jan. 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Basics of AC drives, p. Overview: slide 5 of 6

- ^ "DC or AC Drives? A Guide for Users of Variable-Speed drives (VSDs)" (PDF). p. 11. Retrieved Mar. 22, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "AC and DC Variable Speed Drives Application Considerations" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved Mar. 22, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Drury, Bill (2009). The Control Techniques Drives and Controls Handbook (2nd ed.). Stevenage, Herts, UK: Institution of Engineering and Technology. p. 474. ISBN 978-1-84919-101-2.

- ^ a b c Morris, Ewan. "A Guide to Standard Medium Voltage Variable Speed Drives, Part 2" (PDF). pp. 7-13. Retrieved Mar. 16, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Paes, Richard (2011). "An Overview of Medium Voltage AC Adjustable Speed Drives and IEEE Std. 1566 – Standard for Performance of Adjustable Speed AC Drives Rated 375 kW and Larger". Joint Power Engineering Society-Industrial Applications Society Technical Seminar. IEEE Southern Alberta Chapter: pp. 1–78.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McMurray, William (1988). "Power Electronic Circuit Topology". Proceedings of the IEEE. 76 (4): 428–437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Carrow, Robert S. (2000). Electrician's Technical Reference: Variable Frequency Drives. Albany, NY: Delmar Thomson Learning. p. 51. ISBN 0-7668-1923-X.

- ^ Drury, p. 6

- ^ Sandy, Williams (2003). "Understanding VSDs with ESPs - A Practical Checklist". Society of Petroleum Engineers.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Drury, pp. 6-9

- ^ "ACS800 Catalog - Single Drives 0.55 to 5600 kW". July 19, 2009.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wu, Bin (2005). "High-Power Converters and AC Drives" (PDF). IEEE PES. p. slide 22. Retrieved Feb. 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bartos, Frank J. (Feb. 1, 2000). "Medium-Voltage AC Drives Shed Custom Image". Control Engineering. Reed Business Information.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Lockley, Bill (2008). "Standard 1566 for (Un)Familiar Hands". IEEE Industry Applications Magazine. 14 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1109/MIA.2007.909800.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wu, slide 159

- ^ a b Klug, Dieter-Rolf (2005). "High Power Medium Voltage Drives - Innovations, Portfolio, Trends". European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications. doi:10.1109/EPE.2005.219669.

{{cite conference}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "MV Topologies Comparisons & Features-Benefits" (PDF). Retrieved Feb. 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bose (2006) pp. Chapter 6–8, especially pp. 328, 397, 481

- ^ "Variable Speed Pumping, A Guide to Successful Applications, Executive Summary" (PDF). USDOE - Europump - Hydraulic Institute. May 2004. p. 9, Fig. ES-7. Retrieved Jan. 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Wu, Slide 159

- ^ Rashid, Muhammad H., (Ed.) (2006). Power Electronics Handbook: Devices, Circuits, and Applications (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Academic. p. 903. ISBN 978-0-12-088479-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rodriguez, J. (2002). "Multilevel Inverters: A Survey of Topologies, Controls, and Applications". IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 49 (4): 724–738. doi:10.1109/TIE.2002.801052.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Ikonen, Mika; et al. (2005). "Two-Level and Three-Level Converter Comparison in Wind Power Application" (PDF). Lappeenranta University of Technology.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Bose (2006), p. 183

- ^ Janssen, Hansen (2000). "Harmonic Cancellation by Mixing Non-Linear Single-Phase and Three-Phase Loads". IEEE Trans. on Industry Applications. 36 (1).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Guide to Harmonics with AC Drives - Technical Guide No. 6" (PDF). May 17, 2002. Retrieved Jul. 29, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "IEEE Std 519 - IEEE Recommended Practices and Requirements for Harmonic Control in Electrical Power Systems". 1992. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.1993.114370.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|[publisher=ignored (help) - ^ IEEE 519, pp. 69-70

- ^ Skibinski, Gary (2004). "Line and Load Friendly Drive Solutions for Long Length Cable Applications in Electrical Submersible Pump Applications". Fifty-First Annual Conference Petroleum and Chemical Industry Technical Conference. IEEE: 269–278. doi:10.1109/PCICON.2004.1352810.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Application Report Long Drive/Motor Leads" (PDF). Retrieved Feb. 14, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Malfait, A. (1994). "Audible Noise and Losses in Variable Speed Induction Motor Drives: Influence of the Squirrel Cage Design and the Switching Frequency". 29th Annual Meeting Proceedings of IEEE Industry Applications Society: 693–700.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Who Cares About Carrier Frequency?" (PDF). Retrieved Feb. 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Skibinski, p. 274

- ^ Novak, Peter. "The Basics of Variable-Frequency Drives". EC&M. Retrieved Apr. 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Text "May 1, 2009" ignored (help) - ^ Finlayson, P.T. (1998). "Output filters for PWM drives with induction motors". IEEE Industry Applications Mazagine. 4 (1): 46–52.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yung, Chuck (2007). "Bearings and Electricity Don't Match". PlantServices.com [Plant Services]. Itasca, IL: PtmanMedia: pp. 1–2.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Bearing Currents in Modern AC Drive Systems - Technical Guide No. 5" (PDF). Dec. 1, 1999. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Swamy, M. (2008). "Present State and a Futuristic Vision of Motor Drive Technology". Proceedings of 11th International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment, 2008 (OPTIM 2008). IEEE. pp. XLV–LVI, Fig. 16.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "EMC Compliant Installation and Configuration for a Power Drive System - Technical Guide No. 3" (PDF). Apr. 11, 2008. Retrieved Jul. 29, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Basics of AC Drives, pp. Hardware - Part 1: slides 9-10 of 11

- ^ Technical Guide No. 8, pp. 26-30

- ^ a b Dubey, Gopal K. (2001). Fundamentals of Electrical Drives (2 ed.). Pangbourne: Alpha Science Int. ISBN 1-84265-083-1.

- ^ Rashid, p. 902, Table 33.13

- ^ Campbell, pp. 70–190