Black kite

| Black Kite | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black Kite, Milvus migrans | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. migrans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Milvus migrans (Boddaert, 1783)

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

5, see text | |

| |

| Black and Yellow-billed Kite ranges. Orange: summer only Green: all year Blue: winter only | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Black Kite (Milvus migrans) is a medium-sized bird of prey in the family Accipitridae, which also includes many other diurnal raptors. Unlike others of the group, they are opportunistic hunters and are more likely to scavenge. They spend a lot of time soaring and gliding in thermals in search of food. Their angled wing and distinctive forked tail make them easy to identify. This kite is widely distributed through the temperate and tropical parts of Eurasia and parts of Australasia and Oceania, with the temperate region populations tending to be migratory. Several subspecies are recognized and formerly had their own English names. The European populations are small, but the South Asian population is very large.

Description

The Black Kite can be distinguished from the Red Kite by its slightly smaller size, less forked tail, visible in flight and generally dark plumage without any rufous. The sexes are alike. The upper plumage is brown but the head and neck tend to be paler. The patch behind the eye appears darker. The outer flight feathers are black and the feathers have dark cross bars and are mottled at the base. The lower parts of the body are pale brown, becoming lighter towards the chin. The body feathers have dark shafts giving it a streaked appearance. The cere and gape are yellow but the bill is black (unlike in the Yellow-billed Kite). The legs are yellow and the claws are black. They have a distinctive shrill whistle followed by a rapid whinnying call.[2]

Systematics and taxonomy

The Red Kite has been known to hybridize with the Black Kite (in captivity where both species were kept together, and in the wild on the Cape Verde Islands).[3]

Recent DNA studies suggest that the yellow-billed, African races, parasitus and aegyptius, differ significantly from Black Kites in the Eurasian clade, and should be considered as a separate, allopatric species Yellow-billed Kite, M. aegyptius.[4] They occur throughout Africa except for the Congo basin and the Sahara Desert. There have been some suggestions that the Black-eared Kite (M. m. lineatus) should be elevated to full species status as M. lineatus, but this is not well supported.[5]

Subspecies

- Milvus migrans migrans (Boddaert, 1783): European Black Kite

- Breeds central, southern and eastern Europe to Tien Shan and south to northwest Pakistan. Winters in Sub-Saharan Africa. The head is whitish.

- Milvus migrans lineatus (J. E. Gray, 1831): Black-eared Kite

- Siberia to Amurland S around Himalaya to N India, N Indochina and S China; Japan. Northern inland birds migrate to E Persian Gulf coast and S Asia in winter. This has a larger pale carpal patch.

- Milvus migrans govinda (Sykes, 1832): Small Indian Kite (formerly Pariah Kite)

- Eastern Pakistan east through tropical India and Sri Lanka to Indochina and Malay Peninsula. Resident. A dark brown kite found throughout the subcontinent. Can be seen circling and soaring in urban areas. Easily distinguished by the shallow forked tail. The name Pariah originates from the Indian caste system and usage of this name is deprecated.[6][7]

- Milvus migrans affinis (Gould, 1838): Fork-tailed Kite

- Sulawesi and possibly Lesser Sunda Islands; Papua New Guinea except mountains; NE and E Australia.

- Milvus migrans formosanus (Kuroda, 1920): Taiwan Kite

Distribution

The species is found in Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia. The temperate populations of this kite tend to be migratory while the tropical ones are resident. European and central Asian birds (subspecies M. m. milvus and Black-eared Kite M. m. lineatus, respectively) are migratory, moving to the tropics in winter, but races in warmer regions such as the Indian M. m. govinda (Pariah Kite), or the Australasian M. m. affinis (Fork-tailed Kite), are resident. In some areas such as in the United Kingdom, the Black Kite occurs only as a wanderer on migration. These birds are usually of the nominate race, but in November 2006 a juvenile of the eastern lineatus, not previously recorded in western Europe, was found in Lincolnshire.[8]

The species is not found in the Indonesian archipelago between the South East Asian mainland and the Wallace Line. Vagrants, most likely of the Black-eared Kite, on occasion range far into the Pacific, out to the Hawaiian islands.[citation needed]

In India, the population of M. m. govinda is particularly large especially in areas of high human population. Here the birds avoid heavily forested regions. A survey in 1967 in the 150 square kilometres of the city of New Delhi produced an estimate of about 2200 pairs or roughly 15 per square kilometer.[2][9]

Behaviour and ecology

Food and foraging

Black Kites are most often seen gliding and soaring on thermals as they search for food. The flight is buoyant and the bird glides with ease, changing directions easily. They will swoop down with their legs lowered to snatch small live prey, fish, household refuse and carrion, for which behaviour they are known in British military slang as the shite-hawk. They are opportunist hunters and have been known to take birds, bats and rodents.[10] They are attracted to smoke and fires, where they seek escaping prey.[11] This behaviour has led to Australian native beliefs that kites spread fires by picking up burning twigs and dropping them on dry grass.[12] The Indian populations are well adapted to living in cities and are found in densely populated areas. Large numbers may be seen soaring in thermals over cities. In some places they will readily swoop and snatch food held by humans.[2][13] Black Kites in Spain prey on nestling waterfowl especially during summer to feed their young. Predation of nests of other pairs of Black Kites has also been noted.[14] Kites have also been seen to tear and carry away the nests of Baya Weavers in an attempt to obtain eggs or chicks.[15]

Flocking and roosting

In winter, kites form large communal roosts. Flocks may fly about before settling at the roost.[13] When migrating, the Black Kite has a greater propensity to form large flocks than other migratory raptors, particularly prior to making a crossing across water.[16] In India, the subspecies govinda shows large seasonal fluctuations with the highest numbers seen from July to October, after the Monsoons, and it has been suggested that they make local movements in response to high rainfall.[17]

Breeding

The breeding season of Black Kites in India begins in winter, the young birds fledging before the monsoons. The nest is a rough platform of twigs and rags placed in a tree. Nest sites may be reused in subsequent years. European birds breed in summer. Birds in the Italian Alps tended to build their nest close to water in steep cliffs or tall trees.[18] Nest orientation may be related to wind and rainfall.[19] The nests may sometimes be decorated with bright materials such as white plastic and a study in Spain suggests that they may have a role in signalling to keep away other kites.[20] After pairing, the male frequently copulates with the female. Unguarded females may be approached by other males, and extra pair copulations are frequent. Males returning from a foraging trip will frequently copulate on return, as this increases the chances of his sperm fertilizing the eggs rather than a different male.[21] Both the male and female take part in nest building, incubation and care of chicks. The typical clutch size is 2 or sometimes 3 eggs.[13][22] The incubation period varies from 30–34 days. Chicks of the Indian population stayed at the nest for nearly two months.[23] Chicks hatched later in European populations appeared to fledge faster. The care of young by the parents also rapidly decreased with the need for adults to migrate.[24][25] Siblings show aggression to each other and often the weaker chick may be killed, but parent birds were found to preferentially feed the smaller chicks in experimentally altered nests.[26] Newly hatched young have down (prepennae) which are sepia on the back and black around the eye and buff on the head, neck and underparts. This is replaced by brownish gray second down (preplumulae). After 9 to 12 days the second down appears on the whole body except the top of the head. Body feathers begin to appear after 18 to 22 days. The feathers on the head become noticeable from the 24th to 29th day. The nestlings initially feed on food fallen at the bottom of the nest and begin to tear flesh after 33–39 days. They are able to stand on their legs after 17–19 days and begin flapping their wings after 27–31 days. After 50 days they begin to move to branches next to the nest.[27][28] Birds are able to breed after their second year.[23] Parent birds guard their nest and will dive aggressively at intruders. Humans who intrude the nest appear to be recognized by birds and singled out for dive attacks.[29]

Mortality factors

Black-eared Kites in Japan were found to accumulate nearly 70% of mercury accumulated from polluted food in the feathers, thus excreting it in the moult process.[30] Black Kites often perch on electric wires and are frequent victims of electrocution.[31][32] Their habit of swooping to pick up dead rodents or other roadkill leads to collisions with vehicles.[33] Instances of mass poisoning as a result of feeding on poisoned voles in agricultural fields have been noted.[34] They are also a major nuisance at some airports, where their size makes them a significant birdstrike hazard.[35]

Like most bird species, they have parasites, several species of endoparasitic trematodes are known[36] and some Digenea species that are transmitted via fishes.[37][38][39]

Birds with abnormal development of a secondary upper mandible have been recorded in govinda[40] and lineatus.[41]

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2011.2

- ^ a b c Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular handbook of Indian birds (4 ed.). Gurney and Jackson, London. pp. 371–373. ISBN 1-4067-4576-6.

- ^ Hille, Sabine and Jean-marc Thiollay (2000). "The imminent extinction of the Kites Milvus milvus fasciicauda and Milvus m. migrans on the Cape Verde Islands". Bird Conservation International. 10 (4): 361–369. doi:10.1017/S0959270900000319.

- ^ Johnson JA, Richard T. Watson and David P. Mindell (2005). "Prioritizing species conservation: does the Cape Verde kite exist?" (PDF). Proc. R. Soc. B. 272 (1570): 1365–1371. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3098. PMC 1560339. PMID 16006325.}

- ^ Schreiber, Arnd; Stubbe, Michael & Stubbe, Annegret (2000). "Red kite (Milvus milvus) and black kite (M. migrans): minute genetic interspecies distance of two raptors breeding in a mixed community (Falconiformes: Accipitridae)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 69 (3): 351–365. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2000.tb01210.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Agoramoorthy, G (2005). "Disallow caste discrimination in biological and social contexts" (PDF). Current Science. 89 (5): 727.

- ^ Blanford WT (1896). Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 3. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 374–378.

- ^ Badley, John and Philip Hyde (2006). "The Black-eared Kite in Lincolnshire - a new British bird". Birding World. 19 (11): 465–470.

- ^ Galushin V M (1971). "A huge urban population of birds of prey in Delhi, India". Ibis. 113: 552.

- ^ Narayanan, E (1989). "Pariah Kite Milvus migrans capturing Whitebreasted Kingfisher Halcyon smyrnensis". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 86 (3): 445.

- ^ Hollands, David (1984). Eagles, hawks, and falcons of Australia. Nelson. ISBN 0-17-006411-5.

- ^ Chisholm AH (1971). "The use by birds of tools and playthings". Vict. Nat. 88: 180–188.

- ^ a b c Ali, S & S D Ripley (1978). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 1 (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 226–230. ISBN 0-19-562063-1.

- ^ Veiga, J. P. and Hiraldo, F. (1990). "Food habits and the survival and growth of nestlings in two sympatric kites (Milvus milvus and Milvus migrans)". Holarct. Ecol. 13: 62–71.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wesley,H Daniel; Relton,A; Moses,A Alagappa (1991). "A strange predatory habit of the Pariah Kite Milvus migrans". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 88 (1): 110–111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Agostini N & A Duchi (1994). "Water-crossing behavior of Black Kites (Milvus migrans) during migration" (PDF). Bird Behaviour. 10: 45–48. doi:10.3727/015613894791748935.

- ^ Mahabal, Anil & DB Bastawade (1985). "Population ecology and communal roosting behaviour of pariah kite Milvus migrans govinda in Pune (Maharashtra)". J. Bombay. Nat. Hist. Soc. 82 (2): 337–346.

- ^ Sergio, Fabrizio; Paolo Pedrini and Luigi Marchesi (2003). "Adaptive selection of foraging and nesting habitat by black kites (Milvus migrans) and its implications for conservation: a multi-scale approach". Biological Conservation. 112 (3): 351–362. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00332-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Viñuela J & C Sunyer (1992). "Nest orientation and hatching success of Black Kites Milvus migrans in Spain". Ibis. 134 (4): 340–345. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1992.tb08013.x.

- ^ Sergio, F; J. Blas; G. Blanco; A. Tanferna; L. López; J. A. Lemus; F. Hiraldo (2011). "Raptor Nest Decorations Are a Reliable Threat Against Conspecifics". Science. 331 (6015): 327–330. doi:10.1126/science.1199422. PMID 21252345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koga, K. and Shiraishi, S. (1994). "Copulation behaviour of the Black Kite Milvus migrans in Nagasaki Peninsula". Bird Study. 41 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1080/00063659409477194.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kimiya Koga, Satoshi Siraishi and Teru Aki Uchida (1989). "Breeding Ecology of the Black-eared Kite Milvus migrans lineatus in the Nagasaki Peninsula, Kyushu". Jap. J. Ornithol. 38 (2): 57–66. doi:10.3838/jjo.38.57.

- ^ a b Desai,JH; Malhotra,AK (1979). "Breeding biology of the Pariah Kite Milvus migrans at Delhi Zoological Park". Ibis. 121 (3): 320–325. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1979.tb06849.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bustamante J. & Hiraldo F. (1989). "Post-fledging dependence period and maturation of flight skills in the Black Kite Milvus migrans". Bird Study. 56: 199–204.

- ^ Bustamante, J (1994). "Family break-up in Black and Red Kites Milvus migrans and Milvus milvus:is time of independence an offspring decision" (PDF). Ibis. 136 (2): 176–184. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1994.tb01082.x.

- ^ Viñuela, Javier (1999). "Sibling aggression, hatching asynchrony, and nestling mortality in the black kite ( Milvus migrans )". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 45 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1007/s002650050537.

- ^ Desai, J. H. & A. K. Malhotra (1980). "Embryonic development of Pariah Kite Milvus migrans govinda". J. Yamashina Inst. Ornith. 12: 82–86.

- ^ Koga, Kimiya (1989). "Growth and Development of the Black-eared Kite Milvus migrans lineatus". Japanese Journal of Ornithology. 38 (1): 31–42. doi:10.3838/jjo.38.31.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Malhotra,AK (1990). "Site fidelity and power of recognition in Pariah Kite Milvus migrans govinda". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 87 (3): 458.

- ^ Honda, K; T Nasu & R Tatsukawa (1986). "Seasonal changes in mercury accumulation in the black-eared kite, Milvus migrans lineatus". Environmental Pollution Series A, Ecological and Biological. 42 (4): 325–334. doi:10.1016/0143-1471(86)90016-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferrer, Miguel; Manuel de la Riva and Javier Castroviejo (1991). "Electrocution of Raptors on Power Lines in Southwestern Spain". Journal of Field Ornithology. 62 (2): 181–190.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Janss, GFE (2000). "Avian mortality from power lines: a morphologic approach of a species-specific mortality" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 95 (3): 353–359. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00021-5.

- ^ Cooper JE (1973). "Post-mortem findings in East African birds of prey" (PDF). J. Wildlife Diseases. 9 (4): 368–375.

- ^ Mendelssohn, H; Paz, U (1977). "Mass mortality of birds of prey caused by Azodrin, an organophosphorus insecticide". Biological Conservation. 11 (3): 163. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(77)90001-5.

- ^ Owino A; N Biwott;G Amutete (2004). "Bird strike incidents involving Kenya Airways flights at three Kenyan airports, 1991-2001". African Journal of Ecology. 42 (2): 122–128. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2004.00507.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karyakarte PP (1970). "A new species of Echinochasmus (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) from the kite, Milvus migrans (Boddaert), in India". Rivista di Parassitologia. 31 (2): 113–6.

- ^ Seo M;Guk SM; Chai JY;Sim S; Sohn WM (2008). "Holostephanus metorchis (Digenea: Cyathocotylidae) from Chicks Experimentally Infected with Metacercariae from a Fish, Pseudorasbora parva, in the Republic of Korea". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 46 (2): 83–6. doi:10.3347/kjp.2008.46.2.83. PMC 2532613. PMID 18552543.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lal, Makund Behari (1939). "Studies in Helminthology-Trematode parasites of birds". Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences. Section B. 10 (2): 111–200.

- ^ Sheena, P. (2007). "The life cycle of Mesostephanus indicum Mehra, 1947 (Digenea: Cyathocotylidae)". Parasitology Research. 101 (4): 1015–1018. doi:10.1007/s00436-007-0579-7. PMID 17514481.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rawal UM (1971). "Pariah Kite with Double Bill" (PDF). The Auk. 88 (1): 166.

- ^ Biswas, Biswamoy (1956). "A Large Indian Kite Milvus migrans lineatus (Gray) with a split bill". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 53 (3): 474–475.

Further reading

- Desai, J. H.; Malhotra, A. K. (1982). "Annual gonadal cycle of Black Kite Milvus migrans govinda". J. Yamashina Inst. Orn. 14: 143–150.

- Hardy, J. (1985). "Black Kite capturing small passerines". Australasian Raptor Association News. 6: 14.

- American Ornithologists' Union (2000). "Forty-second supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-list of North American Birds". Auk. 117 (3): 847–858. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2000)117[0847:FSSTTA]2.0.CO;2.

- Crochet Pierre-André (2005). "Recent DNA studies of kites". Birding World. 18 (12): 486–488.

- Forsman Dick (2003). "Identification of Black-eared Kite". Birding World. 16 (4): 156–60.

External links

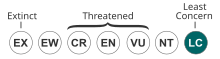

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Kites (birds)

- Birds of Africa

- Birds of Asia

- Birds of Armenia

- Birds of Iran

- Birds of Pakistan

- Birds of Palestine

- Birds of Southeast Asia

- Birds of Bangladesh

- Birds of India

- Birds of Thailand

- Birds of Europe

- Birds of Turkey

- Milvus

- Birds of South Australia

- Birds of Western Australia

- Birds of South Africa

- Birds of Western Sahara