Glycolysis

Glycolysis (from glycose, an older term[1] for glucose + -lysis degradation) is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose C6H12O6, into pyruvate, CH3COCOO− + H+. The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy compounds ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and NADH (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide).[2]

Glycolysis is a definite sequence of ten reactions involving ten intermediate compounds (one of the steps involves two intermediates). The intermediates provide entry points to glycolysis. For example, most monosaccharides, such as fructose, glucose, and galactose, can be converted to one of these intermediates. The intermediates may also be directly useful. For example, the intermediate dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) is a source of the glycerol that combines with fatty acids to form fat.

It occurs, with variations, in nearly all organisms, both aerobic and anaerobic. The wide occurrence of glycolysis indicates that it is one of the most ancient known metabolic pathways.[3] It occurs in the cytosol of the cell.

The most common type of glycolysis is the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas (EMP pathway), which was first discovered by Gustav Embden, Otto Meyerhof, and Jakub Karol Parnas. Glycolysis also refers to other pathways, such as the Entner–Doudoroff pathway and various heterofermentative and homofermentative pathways. However, the discussion here will be limited to the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway.[4]

The entire glycolysis pathway can be separated into two phases:[5]

- The Preparatory Phase – in which ATP is consumed and is hence also known as the investment phase

- The Pay Off Phase – in which ATP is produced.

Overview

The overall reaction of glycolysis is:

| D-[Glucose] | [Pyruvate] | ||||

|

+ 2 [NAD]+ + 2 [ADP] + 2 [P]i | File:Biochem reaction arrow foward NNNN horiz med.png | 2 |

|

+ 2 [NADH] + 2 H+ + 2 [ATP] + 2 H2O |

The use of symbols in this equation makes it appear unbalanced with respect to oxygen atoms, hydrogen atoms, and charges. Atom balance is maintained by the two phosphate (Pi) groups:[6]

- each exists in the form of a hydrogen phosphate anion (HPO42−), dissociating to contribute 2 H+ overall

- each liberates an oxygen atom when it binds to an ADP (adenosine diphosphate) molecule, contributing 2 O overall

Charges are balanced by the difference between ADP and ATP. In the cellular environment, all three hydroxy groups of ADP dissociate into −O- and H+, giving ADP3−, and this ion tends to exist in an ionic bond with Mg2+, giving ADPMg-. ATP behaves identically except that it has four hydroxy groups, giving ATPMg2−. When these differences along with the true charges on the two phosphate groups are considered together, the net charges of −4 on each side are balanced.

For simple fermentations, the metabolism of one molecule of glucose to two molecules of pyruvate has a net yield of two molecules of ATP. Most cells will then carry out further reactions to 'repay' the used NAD+ and produce a final product of ethanol or lactic acid. Many bacteria use inorganic compounds as hydrogen acceptors to regenerate the NAD+.

Cells performing aerobic respiration synthesize much more ATP, but not as part of glycolysis. These further aerobic reactions use pyruvate and NADH + H+ from glycolysis. Eukaryotic aerobic respiration produces approximately 34 additional molecules of ATP for each glucose molecule, however most of these are produced by a vastly different mechanism to the substrate-level phosphorylation in glycolysis.

The lower-energy production, per glucose, of anaerobic respiration relative to aerobic respiration, results in greater flux through the pathway under hypoxic (low-oxygen) conditions, unless alternative sources of anaerobically oxidizable substrates, such as fatty acids, are found.

| Metabolism of common monosaccharides, including glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, glycogenesis and glycogenolysis |

|---|

|

Elucidation of the pathway

In 1860, Louis Pasteur discovered that microorganisms are responsible for fermentation. In 1897, Eduard Buchner found that extracts of certain cells can cause fermentation. In 1905, Arthur Harden and William Young along with Nick Sheppard determined that a heat-sensitive high-molecular-weight subcellular fraction (the enzymes) and a heat-insensitive low-molecular-weight cytoplasm fraction (ADP, ATP and NAD+ and other cofactors) are required together for fermentation to proceed. The details of the pathway were eventually determined by 1940, with a major input from Otto Meyerhof and some years later by Luis Leloir. The biggest difficulties in determining the intricacies of the pathway were due to the very short lifetime and low steady-state concentrations of the intermediates of the fast glycolytic reactions.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Sequence of reactions

Preparatory phase

The first five steps are regarded as the preparatory (or investment) phase, since they consume energy to convert the glucose into two three-carbon sugar phosphates[5] (G3P).

| The first step in glycolysis is phosphorylation of glucose by a family of enzymes called hexokinases to form glucose 6-phosphate (G6P). This reaction consumes ATP, but it acts to keep the glucose concentration low, promoting continuous transport of glucose into the cell through the plasma membrane transporters. In addition, it blocks the glucose from leaking out – the cell lacks transporters for G6P, and free diffusion out of the cell is prevented due to the charged nature of G6P. Glucose may alternatively be formed from the phosphorolysis or hydrolysis of intracellular starch or glycogen.

In animals, an isozyme of hexokinase called glucokinase is also used in the liver, which has a much lower affinity for glucose (Km in the vicinity of normal glycemia), and differs in regulatory properties. The different substrate affinity and alternate regulation of this enzyme are a reflection of the role of the liver in maintaining blood sugar levels. Cofactors: Mg2+ |

| ||||||||||||||

| G6P is then rearranged into fructose 6-phosphate (F6P) by glucose phosphate isomerase. Fructose can also enter the glycolytic pathway by phosphorylation at this point.

The change in structure is an isomerization, in which the G6P has been converted to F6P. The reaction requires an enzyme, phosphohexose isomerase, to proceed. This reaction is freely reversible under normal cell conditions. However, it is often driven forward because of a low concentration of F6P, which is constantly consumed during the next step of glycolysis. Under conditions of high F6P concentration, this reaction readily runs in reverse. This phenomenon can be explained through Le Chatelier's Principle. Isomerization to a keto sugar is necessary for carbanion stabilization in the fourth reaction step (below). |

| ||||||||||||||

| The energy expenditure of another ATP in this step is justified in 2 ways: The glycolytic process (up to this step) is now irreversible, and the energy supplied destabilizes the molecule. Because the reaction catalyzed by Phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK-1) is coupled to the hydrolysis of ATP, an energetically favorable step, it is, in essence, irreversible, and a different pathway must be used to do the reverse conversion during gluconeogenesis. This makes the reaction a key regulatory point (see below). This is also the rate-limiting step.

Furthermore, the second phosphorylation event is necessary to allow the formation of two charged groups (rather than only one) in the subsequent step of glycolysis, ensuring the prevention of free diffusion of substrates out of the cell. The same reaction can also be catalyzed by pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinase (PFP or PPi-PFK), which is found in most plants, some bacteria, archea, and protists, but not in animals. This enzyme uses pyrophosphate (PPi) as a phosphate donor instead of ATP. It is a reversible reaction, increasing the flexibility of glycolytic metabolism.[7] A rarer ADP-dependent PFK enzyme variant has been identified in archaean species.[8] Cofactors: Mg2+ |

| ||||||||||||||

| Destabilizing the molecule in the previous reaction allows the hexose ring to be split by aldolase into two triose sugars, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, a ketone, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, an aldehyde. There are two classes of aldolases: class I aldolases, present in animals and plants, and class II aldolases, present in fungi and bacteria; the two classes use different mechanisms in cleaving the ketose ring.

Electrons delocalized in the carbon-carbon bond cleavage associate with the alcohol group. The resulting carbanion is stabilized by the structure of the carbanion itself via resonance charge distribution and by the presence of a charged ion prosthetic group. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triosephosphate isomerase rapidly interconverts dihydroxyacetone phosphate with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GADP) that proceeds further into glycolysis. This is advantageous, as it directs dihydroxyacetone phosphate down the same pathway as glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, simplifying regulation. |

| ||||||||||||||

Pay-off phase

The second half of glycolysis is known as the pay-off phase, characterised by a net gain of the energy-rich molecules ATP and NADH.[5] Since glucose leads to two triose sugars in the preparatory phase, each reaction in the pay-off phase occurs twice per glucose molecule. This yields 2 NADH molecules and 4 ATP molecules, leading to a net gain of 2 NADH molecules and 2 ATP molecules from the glycolytic pathway per glucose.

| The triose sugars are dehydrogenated and inorganic phosphate is added to them, forming 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate.

The hydrogen is used to reduce two molecules of NAD+, a hydrogen carrier, to give NADH + H+ for each triose. Hydrogen atom balance and charge balance are both maintained because the phosphate (Pi) group actually exists in the form of a hydrogen phosphate anion (HPO42-),[6] which dissociates to contribute the extra H+ ion and gives a net charge of -3 on both sides. |

| ||||||||||||||

| This step is the enzymatic transfer of a phosphate group from 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate to ADP by phosphoglycerate kinase, forming ATP and 3-phosphoglycerate. At this step, glycolysis has reached the break-even point: 2 molecules of ATP were consumed, and 2 new molecules have now been synthesized. This step, one of the two substrate-level phosphorylation steps, requires ADP; thus, when the cell has plenty of ATP (and little ADP), this reaction does not occur. Because ATP decays relatively quickly when it is not metabolized, this is an important regulatory point in the glycolytic pathway..

ADP actually exists as ADPMg-, and ATP as ATPMg2-, balancing the charges at -5 both sides. Cofactors: Mg2+ |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Phosphoglycerate mutase now forms 2-phosphoglycerate. |

| ||||||||||||||

| Enolase next forms phosphoenolpyruvate from 2-phosphoglycerate.

Cofactors: 2 Mg2+: one "conformational" ion to coordinate with the carboxylate group of the substrate, and one "catalytic" ion that participates in the dehydration. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| A final substrate-level phosphorylation now forms a molecule of pyruvate and a molecule of ATP by means of the enzyme pyruvate kinase. This serves as an additional regulatory step, similar to the phosphoglycerate kinase step.

Cofactors: Mg2+ |

| ||||||||||||||

Regulation

Glycolysis is regulated by slowing down or speeding up certain steps in the glycolysis pathway. This is accomplished by inhibiting or activating the enzymes that are involved. The steps that are regulated may be determined by calculating the change in free energy, ΔG, for each step. If a step's products and reactants are in equilibrium, then the step is assumed not to be regulated. Since the change in free energy is zero for a system at equilibrium, any step with a free energy change near zero is not being regulated. If a step is being regulated, then that step's enzyme is not converting reactants into products as fast as it could, resulting in a build-up of reactants, which would be converted to products if the enzyme were operating faster. Since the reaction is thermodynamically favorable, the change in free energy for the step will be negative. A step with a large negative change in free energy is assumed to be regulated.

Free energy changes

| Compound | Concentration / mM |

|---|---|

| glucose | 5.0 |

| glucose-6-phosphate | 0.083 |

| fructose-6-phosphate | 0.014 |

| fructose-1,6-bisphosphate | 0.031 |

| dihydroxyacetone phosphate | 0.14 |

| glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate | 0.019 |

| 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate | 0.001 |

| 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate | 4.0 |

| 3-phosphoglycerate | 0.12 |

| 2-phosphoglycerate | 0.03 |

| phosphoenolpyruvate | 0.023 |

| pyruvate | 0.051 |

| ATP | 1.85 |

| ADP | 0.14 |

| Pi | 1.0 |

| |

The change in free energy, ΔG, for each step in the glycolysis pathway can be calculated using ΔG = ΔG°' + RTln Q, where Q is the reaction quotient. This requires knowing the concentrations of the metabolites. All of these values are available for erythrocytes, with the exception of the concentrations of NAD+ and NADH. The ratio of NAD+ to NADH in the cytoplasm is approximately 1000, which makes the oxidation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (step 6) more favourable.

Using the measured concentrations of each step, and the standard free energy changes, the actual free energy change can be calculated. (Neglecting this is very common - the delta G of ATP hydrolysis in cells is not the standard free energy change of ATP hydrolysis quoted in textbooks).

| Step | Reaction | ΔG°' / (kJ/mol) | ΔG / (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | glucose + ATP4- → glucose-6-phosphate2- + ADP3- + H+ | -16.7 | -34 |

| 2 | glucose-6-phosphate2- → fructose-6-phosphate2- | 1.67 | -2.9 |

| 3 | fructose-6-phosphate2- + ATP4- → fructose-1,6-bisphosphate4- + ADP3- + H+ | -14.2 | -19 |

| 4 | fructose-1,6-bisphosphate4- → dihydroxyacetone phosphate2- + glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate2- | 23.9 | -0.23 |

| 5 | dihydroxyacetone phosphate2- → glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate2- | 7.56 | 2.4 |

| 6 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate2- + Pi2- + NAD+ → 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate4- + NADH + H+ | 6.30 | -1.29 |

| 7 | 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate4- + ADP3- → 3-phosphoglycerate3- + ATP4- | -18.9 | 0.09 |

| 8 | 3-phosphoglycerate3- → 2-phosphoglycerate3- | 4.4 | 0.83 |

| 9 | 2-phosphoglycerate3- → phosphoenolpyruvate3- + H2O | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| 10 | phosphoenolpyruvate3- + ADP3- + H+ → pyruvate- + ATP4- | -31.7 | -23.0 |

From measuring the physiological concentrations of metabolites in an erythrocyte it seems that about seven of the steps in glycolysis are in equilibrium for that cell type. Three of the steps — the ones with large negative free energy changes — are not in equilibrium and are referred to as irreversible; such steps are often subject to regulation.

Step 5 in the figure is shown behind the other steps, because that step is a side-reaction that can decrease or increase the concentration of the intermediate glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. That compound is converted to dihydroxyacetone phosphate by the enzyme triose phosphate isomerase, which is a catalytically perfect enzyme; its rate is so fast that the reaction can be assumed to be in equilibrium. The fact that ΔG is not zero indicates that the actual concentrations in the erythrocyte are not accurately known.

Biochemical logic

The existence of more than one point of regulation indicates that intermediates between those points enter and leave the glycolysis pathway by other processes. For example, in the first regulated step, hexokinase converts glucose into glucose-6-phosphate. Instead of continuing through the glycolysis pathway, this intermediate can be converted into glucose storage molecules, such as glycogen or starch. The reverse reaction, breaking down, e.g., glycogen, produces mainly glucose-6-phosphate; very little free glucose is formed in the reaction. The glucose-6-phosphate so produced can enter glycolysis after the first control point.

In the second regulated step (the third step of glycolysis), phosphofructokinase converts fructose-6-phosphate into fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, which then is converted into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. The dihydroxyacetone phosphate can be removed from glycolysis by conversion into glycerol-3-phosphate, which can be used to form triglycerides.[11] On the converse, triglycerides can be broken down into fatty acids and glycerol; the latter, in turn, can be converted into dihydroxyacetone phosphate, which can enter glycolysis after the second control point.

Regulation

The three regulated enzymes are hexokinase, phosphofructokinase, and pyruvate kinase.

The flux through the glycolytic pathway is adjusted in response to conditions both inside and outside the cell. The rate in liver is regulated to meet major cellular needs: (1) the production of ATP, (2) the provision of building blocks for biosynthetic reactions, and (3) to lower blood glucose, one of the major functions of the liver. When blood sugar falls, glycolysis is halted in the liver to allow the reverse process, gluconeogenesis. In glycolysis, the reactions catalyzed by hexokinase, phosphofructokinase, and pyruvate kinase are effectively irreversible in most organisms. In metabolic pathways, such enzymes are potential sites of control, and all three enzymes serve this purpose in glycolysis.

Hexokinase

In animals, regulation of blood glucose levels by the pancreas in conjunction with the liver is a vital part of homeostasis. In liver cells, extra G6P (glucose-6-phosphate) may be converted to G1P for conversion to glycogen, or it is alternatively converted by glycolysis to acetyl-CoA and then citrate. Excess citrate is exported to the cytosol, where ATP citrate lyase will regenerate acetyl-CoA and OAA. The acetyl-CoA is then used for fatty acid synthesis and cholesterol synthesis, two important ways of utilizing excess glucose when its concentration is high in blood. Liver contains both hexokinase and glucokinase; the latter catalyses the phosphorylation of glucose to G6P and is not inhibited by G6P. Thus, it allows glucose to be converted into glycogen, fatty acids, and cholesterol even when hexokinase activity is low.[12] This is important when blood glucose levels are high. During hypoglycemia, the glycogen can be converted back to G6P and then converted to glucose by the liver-specific enzyme glucose 6-phosphatase. This reverse reaction is an important role of liver cells to maintain blood sugars levels during fasting. This is critical for brain function, since the brain utilizes glucose as an energy source under most conditions.

Phosphofructokinase

Phosphofructokinase is an important control point in the glycolytic pathway, since it is one of the irreversible steps and has key allosteric effectors, AMP and fructose 2,6-bisphosphate (F2,6BP).

Fructose 2,6-bisphosphate (F2,6BP) is a very potent activator of phosphofructokinase (PFK-1), which is synthesised when F6P is phosphorylated by a second phosphofructokinase (PFK2). In liver, when blood sugar is low and glucagon elevates cAMP, PFK2 is phosphorylated by protein kinase A. The phosphorylation inactivates PFK2, and another domain on this protein becomes active as fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase, which converts F2,6BP back to F6P. Both glucagon and epinephrine cause high levels of cAMP in the liver. The result of lower levels of liver fructose-2,6-bisphosphate is a decrease in activity of phosphofructokinase and an increase in activity of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, so that gluconeogenesis (in essence, "glycolysis in reverse") is favored. This is consistent with the role of the liver in such situations, since the response of the liver to these hormones is to release glucose to the blood.

ATP competes with AMP for the allosteric effector site on the PFK enzyme. ATP concentrations in cells are much higher than those of AMP, typically 100-fold higher,[13] but the concentration of ATP does not change more than about 10% under physiological conditions, whereas a 10% drop in ATP results in a 6-fold increase in AMP.[14] Thus, the relevance of ATP as an allosteric effector is questionable. An increase in AMP is a consequence of a decrease in energy charge in the cell.

Citrate inhibits phosphofructokinase when tested in vitro by enhancing the inhibitory effect of ATP. However, it is doubtful that this is a meaningful effect in vivo, because citrate in the cytosol is utilized mainly for conversion to acetyl-CoA for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis.

Pyruvate kinase

This enzyme catalyzes the last step of glycolysis, in which pyruvate and ATP are formed. Regulation of this enzyme is discussed in the main topic, pyruvate kinase.

Post-glycolysis processes

The overall process of glycolysis is:

- glucose + 2 NAD+ + 2 ADP + 2 Pi → 2 pyruvate + 2 NADH + 2 H+ + 2 ATP + 2 H2O

If glycolysis were to continue indefinitely, all of the NAD+ would be used up, and glycolysis would stop. To allow glycolysis to continue, organisms must be able to oxidize NADH back to NAD+.

Fermentation

One method of doing this is to simply have the pyruvate do the oxidation; in this process, the pyruvate is converted to lactate (the conjugate base of lactic acid) in a process called lactic acid fermentation:

- pyruvate + NADH + H+ → lactate + NAD+

This process occurs in the bacteria involved in making yogurt (the lactic acid causes the milk to curdle). This process also occurs in animals under hypoxic (or partially anaerobic) conditions, found, for example, in overworked muscles that are starved of oxygen, or in infarcted heart muscle cells. In many tissues, this is a cellular last resort for energy; most animal tissue cannot tolerate anaerobic conditions for an extended period of time.

Some organisms, such as yeast, convert NADH back to NAD+ in a process called ethanol fermentation. In this process, the pyruvate is converted first to acetaldehyde and carbon dioxide, then to ethanol.

Lactic acid fermentation and ethanol fermentation can occur in the absence of oxygen. This anaerobic fermentation allows many single-cell organisms to use glycolysis as their only energy source.

Anaerobic respiration

In the above two examples of fermentation, NADH is oxidized by transferring two electrons to pyruvate. However, anaerobic bacteria use a wide variety of compounds as the terminal electron acceptors in cellular respiration: nitrogenous compounds, such as nitrates and nitrites; sulfur compounds, such as sulfates, sulfites, sulfur dioxide, and elemental sulfur; carbon dioxide; iron compounds; manganese compounds; cobalt compounds; and uranium compounds.

Aerobic respiration

In aerobic organisms, a complex mechanism has been developed to use the oxygen in air as the final electron acceptor.

- First, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA and CO2 within the mitochondria in a process called pyruvate decarboxylation.

- Second, the acetyl-CoA enters the citric acid cycle, also known as Krebs Cycle, where it is fully oxidized to carbon dioxide and water, producing yet more NADH.

- Third, the NADH is oxidized to NAD+ by the electron transport chain, using oxygen as the final electron acceptor. This process creates a hydrogen ion gradient across the inner membrane of the mitochondria.

- Fourth, the proton gradient is used to produce about 2.5 ATP for every NADH oxidized in a process called oxidative phosphorylation.

Intermediates for other pathways

This article concentrates on the catabolic role of glycolysis with regard to converting potential chemical energy to usable chemical energy during the oxidation of glucose to pyruvate. Many of the metabolites in the glycolytic pathway are also used by anabolic pathways, and, as a consequence, flux through the pathway is critical to maintain a supply of carbon skeletons for biosynthesis.

In addition, not all carbon entering the pathway leaves as pyruvate and may be extracted at earlier stages to provide carbon compounds for other pathways.

These metabolic pathways are all strongly reliant on glycolysis as a source of metabolites: and many more.

- Gluconeogenesis

- Lipid metabolism

- Pentose phosphate pathway

- Citric acid cycle, which in turn leads to:

From an anabolic metabolism perspective, the NADH has a role to drive synthetic reactions, doing so by directly or indirectly reducing the pool of NADP+ in the cell to NADPH, which is another important reducing agent for biosynthetic pathways in a cell.

Glycolysis in disease

Genetic diseases

Glycolytic mutations are generally rare due to importance of the metabolic pathway, this means that the majority of occurring mutations result in an inability for the cell to respire, and therefore cause the death of the cell at an early stage. However, some mutations are seen with one notable example being Pyruvate kinase deficiency, leading to chronic hemolytic anemia.

Cancer

Malignant rapidly growing tumor cells typically have glycolytic rates that are up to 200 times higher than those of their normal tissues of origin. This phenomenon was first described in 1930 by Otto Warburg and is referred to as the Warburg effect. The Warburg hypothesis claims that cancer is primarily caused by dysfunctionality in mitochondrial metabolism, rather than because of uncontrolled growth of cells. A number of theories have been advanced to explain the Warburg effect. One such theory suggests that the increased glycolysis is a normal protective process of the body and that malignant change could be primarily caused by energy metabolism.[15]

This high glycolysis rate has important medical applications, as high aerobic glycolysis by malignant tumors is utilized clinically to diagnose and monitor treatment responses of cancers by imaging uptake of 2-18F-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) (a radioactive modified hexokinase substrate) with positron emission tomography (PET).[16][17]

There is ongoing research to affect mitochondrial metabolism and treat cancer by reducing glycolysis and thus starving cancerous cells in various new ways, including a ketogenic diet.

Alzheimer's disease

Disfunctioning glycolysis or glucose metabolism in fronto-temporo-parietal and cingulate cortices has been associated with Alzheimer's disease,[18] probably due to the decreased amyloid β (1-42) (Aβ42) and increased tau, phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)[19]

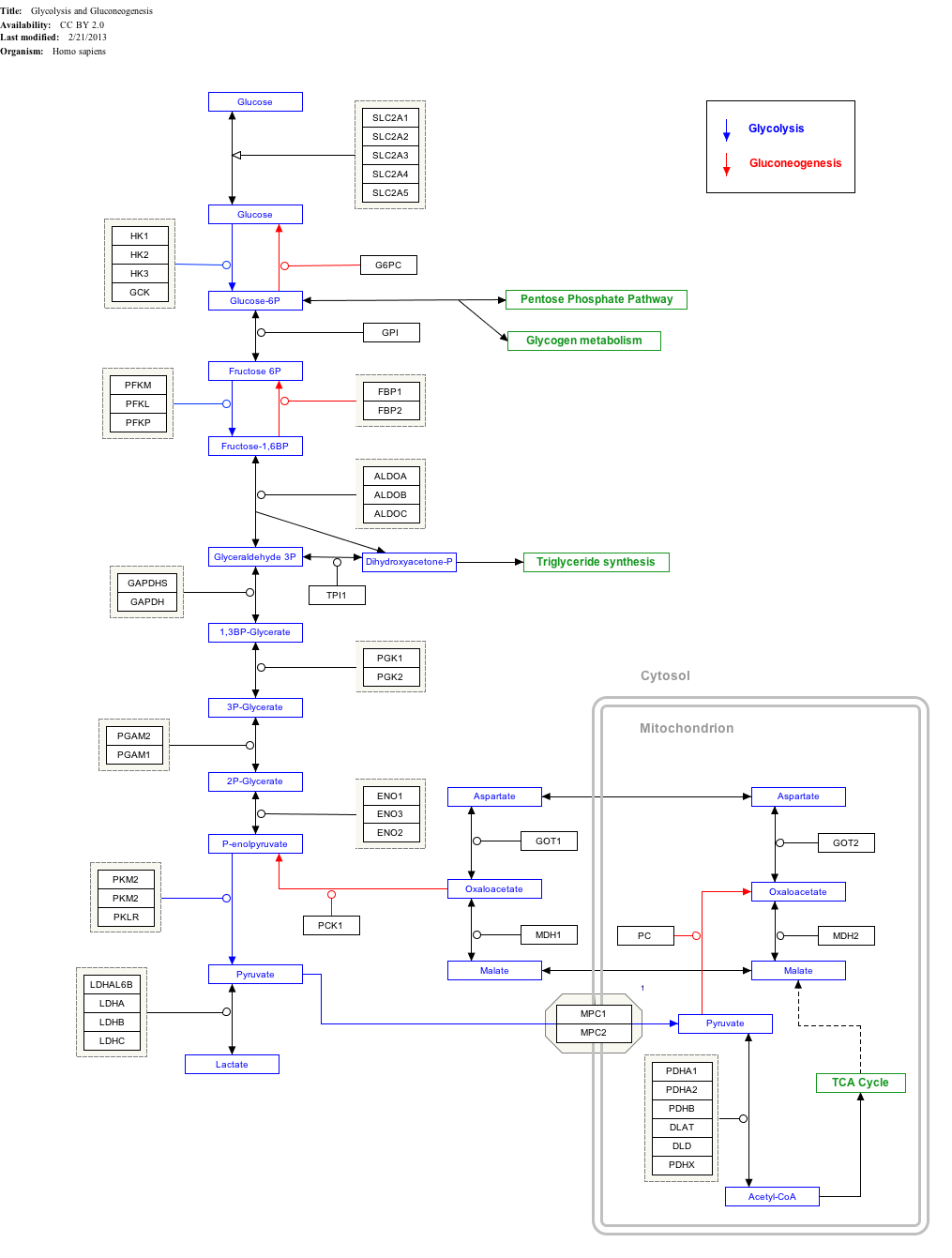

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.[§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "GlycolysisGluconeogenesis_WP534".

Alternative nomenclature

Some of the metabolites in glycolysis have alternative names and nomenclature. In part, this is because some of them are common to other pathways, such as the Calvin cycle.

| This article | Alternative names | Alternative nomenclature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | glucose | Glc | dextrose | |

| 3 | fructose 6-phosphate | F6P | ||

| 4 | fructose 1,6-bisphosphate | F1,6BP | fructose 1,6-diphosphate | FBP, FDP, F1,6DP |

| 5 | dihydroxyacetone phosphate | DHAP | glycerone phosphate | |

| 6 | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate | GADP | 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde | PGAL, G3P, GALP,GAP,TP |

| 7 | 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate | 1,3BPG | glycerate 1,3-bisphosphate, glycerate 1,3-diphosphate, 1,3-diphosphoglycerate |

PGAP, BPG, DPG |

| 8 | 3-phosphoglycerate | 3PG | glycerate 3-phosphate | PGA, GP |

| 9 | 2-phosphoglycerate | 2PG | glycerate 2-phosphate | |

| 10 | phosphoenolpyruvate | PEP | ||

| 11 | pyruvate | Pyr | pyruvic acid | |

See also

References

- ^ Webster's New International Dictionary of the English Language, 2nd ed. (1937) Merriam Company, Springfield, Mass.

- ^ Bailey, Regina. "10 Steps of Glycolysis".

- ^ Romano AH, Conway T. (1996) Evolution of carbohydrate metabolic pathways. Res Microbiol. 147(6–7):448–55 PMID 9084754

- ^ Kim BH, Gadd GM. (2011) Bacterial Physiology and Metabolism, 3rd edition.

- ^ a b c Glycolysis – Animation and Notes

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s11306-008-0142-2, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s11306-008-0142-2instead. - ^ Reeves, R. E. (1974). "Pyrophosphate: D-fructose 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase. A new enzyme with the glycolytic function 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase". J Biol Chem. 249 (24): 7737–7741. PMID 4372217.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Selig, M. (1997). "Comparative analysis of Embden-Meyerhof and Entner-Doudoroff glycolytic pathways in hyperthermophilic archaea and the bacterium Thermotoga". Arch Microbiol. 167 (4): 217–232. PMID 9075622.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Garrett, R.; Grisham, C. M. (2005). Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. p. 584. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/0-534-49011-6|0-534-49011-6[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Garrett, R.; Grisham, C. M. (2005). Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. pp. 582–583. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/0-534-49011-6|0-534-49011-6[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Berg, J. M.; Tymoczko, J. L.; Stryer, L. (2007). Biochemistry (6th ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 622. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/0-534-49011-6|0-534-49011-6[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Voet D., and Voet J. G. (2004). Biochemistry 3rd Edition (New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

- ^ Beis I., and Newsholme E. A. (1975). The contents of adenine nucleotides, phosphagens and some glycolytic intermediates in resting muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates. Biochem J 152, 23-32.

- ^ Voet D., and Voet J. G. (2004). Biochemistry 3rd Edition (New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

- ^ "What is Cancer?". Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "PET Scan: PET Scan Info Reveals ..." Retrieved December 5, 2005.

- ^ "4320139 549..559" (PDF). Retrieved December 5, 2005.

- ^ Hunt, A .; Schonknecht, P; Henze, M; Seidl, U; Haberkorn, U; Schroder, J; et al. (2007). "Reduced cerebral glucose metabolism in patients at risk for Alzheimer's disease". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 155 (2): 147–154. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.003. PMID 17524628.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Hunt, A .; Van Der Flier, WM; Blankenstein, MA; Bouwman, FH; Van Kamp, GJ; Barkhof, F; Scheltens, P; et al. (2008). "CSF and MRI markers independently contribute to the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease". Neurobiology of Aging. 29 (5): 669–675. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.11.018. PMID 17208336.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)

External links

- A Detailed Glycolysis Animation provided by IUBMB (Adobe Flash Required)

- The Glycolytic enzymes in Glycolysis at RCSB PDB

- Glycolytic cycle with animations at wdv.com

- Metabolism, Cellular Respiration and Photosynthesis - The Virtual Library of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at biochemweb.org

- notes on glycolysis at rahulgladwin.com

- The chemical logic behind glycolysis at ufp.pt

- Expasy biochemical pathways poster at ExPASy

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 317 5468