Saving Mr. Banks

| Saving Mr. Banks | |

|---|---|

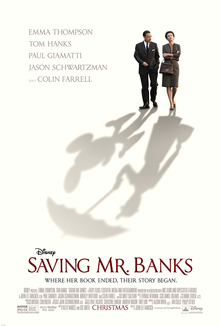

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Lee Hancock |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Schwartzman |

| Edited by | Mark Livolsi |

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 125 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35 million[2] |

| Box office | $112,544,580[3] |

Saving Mr. Banks is a 2013 American-Australian-British biographical comedy-drama film directed by John Lee Hancock from a screenplay written by Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith. Centered on the development of the 1964 Walt Disney Studios film Mary Poppins, the film stars Emma Thompson as author P. L. Travers and Tom Hanks as filmmaker Walt Disney, with supporting performances from Colin Farrell, Paul Giamatti, Jason Schwartzman, Bradley Whitford, Ruth Wilson, B. J. Novak, Rachel Griffiths, and Kathy Baker. Named after the father in Travers' story, the film depicts the author's fortnight-long briefing in 1961 Los Angeles as she is persuaded by Disney, in his attempts to obtain the screen rights to her novels.[4]

Produced by Walt Disney Pictures, Ruby Films and Essential Media and Entertainment in association with BBC Films and Hopscotch Features, Saving Mr. Banks was shot entirely in the Southern California area, primarily at the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, where a majority of the film's narrative takes place.[5][6] The film was released theatrically in the UK on November 29, 2013, and in the United States on December 13, 2013, where it was met with positive reviews, with praise directed towards the acting, screenplay, and production merits—Thompson received BAFTA Award, Golden Globe Award, SAG Award, and Critic's Choice Award nominations for Best Actress, while Thomas Newman received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Score. The film was also a box office success, grossing $112 million worldwide against a $35 million budget.[7]

Plot

In London in 1961, financially struggling author Pamela "P. L." Travers (Emma Thompson) reluctantly agrees to travel to Los Angeles to meet with Walt Disney (Tom Hanks) at the urging of her agent Diarmuid Russell (Ronan Vibert). Disney has been courting Travers for 20 years, seeking to acquire the film rights to her Mary Poppins stories, on account of his daughters' request to make a film based on the character. Travers, however, has been extremely hesitant to allow Disney to adapt her creation to the screen because he is known primarily as a producer of animated films, which Travers openly disdains.

Her youth in Allora, Queensland in 1906 is depicted through flashbacks, and is shown to be the inspiration for much of Mary Poppins. Travers was very close to her handsome and charismatic father Travers Robert Goff (Colin Farrell), who fought a losing battle against alcoholism.

Upon her arrival in Los Angeles, Travers is disgusted by what she feels is the city’s unreality, as well as by the naïve optimism and intrusive friendliness of its inhabitants, personified by her assigned limo driver, Ralph (Paul Giamatti).

At the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, Travers begins collaborating with the creative team assigned to develop Mary Poppins for the screen, screenwriter Don DaGradi (Bradley Whitford), and music composers Richard and Robert Sherman (Jason Schwartzman and B.J. Novak respectively). She finds their presumptions and casual manners as highly improper, a view she also reciprocates on the jocular Disney upon meeting him in person.

Travers’ working relationship with the creative team is difficult from the outset, with her insistence that Mary Poppins is the enemy of sentiment and whimsy. Disney and his associates are puzzled by Travers’ disdain for fantasy, given the fantastical nature of the Mary Poppins story, as well as Travers’ own richly imaginative childhood existence. Travers has particular trouble with the team’s depiction of George Banks. Travers describes Banks’ characterization as completely off-base and leaves a session distraught. The team begins to grasp how deeply personal the Mary Poppins stories are to Travers, and how many of the work’s characters are directly inspired by Travers’ own past.

Travers' collaboration with the team continues, although she is increasingly disengaged as painful memories from her past numb her in the present. Seeking to find out what’s troubling her, Disney invites Travers to Disneyland, which—along with her progressive friendship with Ralph, the creative team’s revisions to George Banks, and the insertion of a new song to close the film—help to soften Travers. Her imagination begins to reawaken, and she engages enthusiastically with the creative team.

This progress is upended, however, when Travers discovers that an animation sequence is being planned for the film, a decision that she has been adamantly against accepting. She confronts and denounces a protesting Disney, angrily declaring that she will not sign over the film rights and returns to London. Disney discovers that Travers is writing under a pen name; her real name being Helen Goff. Equipped with new insight, he departs for London, determined to salvage the film. Appearing unexpectedly at Travers’ residence, Disney opens up—describing his own less-than-ideal childhood, while stressing the healing value of his art—and urges her to shed her deeply rooted disappointment with the world. Travers relents and grants him the film rights.

Three years later, in 1964, Mary Poppins is nearing its world premiere at Grauman's Chinese Theatre. Travers has not been invited because Disney fears that she will give the film negative publicity. Goaded by her agent, Travers returns to Los Angeles, showing up uninvited in Disney’s office, and finagles an invitation to the premiere. She watches Mary Poppins initially with scorn, reacting with particular dismay to the animated sequence. She slowly warms to the film, however, and is ultimately surprised to find herself overcome by emotion, touched by the depiction of George Banks’ redemption, which clearly possesses a powerful personal significance for her.

Historical accuracy

Saving Mr. Banks depicts several events that differ from recorded accounts.[8] The dramatic premise of the script—that Walt Disney had to convince P.L. Travers to hand over the film rights, including the scene when he finally persuades her—is fictionalized, as Disney had already secured the film rights (subject to Travers' approval of the script) when Travers arrived to consult with the Disney staff.[9][10] Disney in fact left Burbank to vacation in Palm Springs, California a few days into Travers' visit to the United States, and was not present at the studio when several of the film's scenes depict him to be in.[11] Therefore, many of the dialogue scenes between Travers and Disney are adapted from letters, telegrams, and telephone correspondence between the two.[11]

The film also depicts Travers coming to amicable terms with Disney, including her approval of his changes to the story.[12] In reality, she never approved of the dilution of the harsher aspects of Mary Poppins' character, felt ambivalent about the music, and hated the use of animation.[13][14] Disney overruled her objections to portions of the final film, citing contract stipulations that he had final cut privilege. After the film's premiere, Travers reportedly approached Disney and told him that the animated sequences had to be removed. Disney dismissed her request, saying, "Pamela, the ship has sailed".[15]

Although the film portrays Travers as being emotionally moved during the premiere of Mary Poppins, presumably due to her feelings about her father,[15] co-screenwriter Kelly Marcel and several critics note that, in real life, Travers was in fact seen crying at the premiere out of anger and frustration over the film,[11][9][15][16] which she felt betrayed the artistic integrity of her characters and work.[17] Resentful at what she considered poor treatment at Disney's hands, Travers vowed to never permit The Walt Disney Company to adapt any of her other novels in any form of media.[18] Travers' last will, in fact, bans any Americans from adapting her works to any form of media.[11] According to the Chicago Tribune, Disney was "indulging in a little revisionist history with an upbeat spin", adding that "the truth was always complicated" and that Travers subsequently viewed the film multiple times.[19]

English writer Brian Sibley found Travers still gun-shy from her experiences with Disney when he was hired to write a possible Mary Poppins sequel in 1980s. Sibley reported that Travers told him, “I could only agree if I could do it on my own terms. I'd have to work with someone I trust.” Nevertheless, while watching the original film together—the first time Travers had seen it since the premiere—she became excited during moments and thought they were excellent, while other parts she considered to be terrible.[20] The sequel never went to production, and when approached to do a stage adaptation in the 1990s, she only acquiesced on the condition that English-born writers and no one from the film production were to be directly involved with the musical's development.[21][22][23]

Although Travers was assigned a limousine driver,[11] the character of Ralph is fictionalized and intended to be an amalgamation of the studio's drivers.[24] In real life, Disney story editor Bill Dover was assigned as Travers' guide and companion during her time in Los Angeles.[11]

Cast

- Emma Thompson as Pamela "P. L." Travers, author of Mary Poppins[25]

- Tom Hanks as Walt Disney, filmmaker and producer of the film

- Annie Rose Buckley as a young P. L. Travers (real name Helen Goff, nicknamed Ginty)

- Colin Farrell as Travers Robert Goff, Pamela's alcoholic, yet loving, father[26][27]

- Ruth Wilson as Margaret Goff, Pamela's mother[28]

- Paul Giamatti as Ralph, Pamela's chauffeur[29][30]

- Bradley Whitford as Don DaGradi, co-writer of the screenplay for Mary Poppins[31]

- B. J. Novak as Robert B. Sherman, composer/lyricist who co-wrote the film's songs with his brother Richard[32]

- Jason Schwartzman as Richard M. Sherman, composer/lyricist who co-wrote the film's songs with his brother Robert[32]

- Kathy Baker as Tommie Wilck,[33] Walt Disney's executive secretary[28][31]

- Melanie Paxson as Dolly (Dolores Vought),[33] Disney's secretary

- Rachel Griffiths as Aunt Ellie, the sister of Pamela's mother[11]

- Ronan Vibert as Diarmuid Russell, Pamela's agent[34]

Dendrie Taylor, Victoria Summer, and Kristopher Kyer appear in minor, non-speaking roles as Lillian Disney, Julie Andrews, and Dick Van Dyke, respectively.[34][35]

Production

Development

In 2002, Australian producer Ian Collie produced a documentary film on P. L. Travers titled The Shadow of "Mary Poppins". During the documentary's production, Collie noticed that there was "an obvious biopic there" and convinced Essential Media and Entertainment to develop a feature film with Sue Smith writing the screenplay.[36] The project attracted the attention of BBC Films, which decided to finance the project, and Ruby Films' Alison Owen, who subsequently hired Kelly Marcel to co-write the screenplay with Smith.[37] Marcel's drafts removed a subplot involving Travers and her son, and divided the story into a two-part narrative: the creative conflict between Travers and Walt Disney, and her dealings with her childhood issues. Marcel's version, however, featured certain intellectual property rights of music and imagery which would be impossible to use without permission from The Walt Disney Company. "There was always that elephant in the room, which is Disney," Collie recalled. "We knew Walt Disney was a key character in the film and we wanted to use quite a bit of the music. We knew we'd eventually have to show Disney." In early 2010, Robert B. Sherman provided producer Alison Owen with an advance copy of a salient chapter from his then upcoming book release, Moose: Chapters From My Life. The chapter entitled, "'Tween Pavement and Stars" contained characterizations and anecdotes which proved seminal to the Kelly Marcel script rewrite, in particular the anecdote about there not being any color red in London.[38][39] In July 2011, while attending the Ischia Film Festival, Owen met with Corky Hale, who offered to present the screenplay to Richard M. Sherman of the Sherman Brothers, music composers of Mary Poppins.[40] Sherman read the screenplay and gave the producers his support.[40] Later that year, Marcel and Smith's screenplay was listed in Franklin Leonard's The Black List, voted by producers as one of the best screenplays that were not in production.[41]

In November 2011, The Walt Disney Studios' president of production, Sean Bailey, was informed of the existence of Marcel's script.[2] Realizing that the screenplay included a depiction of Walt Disney, Bailey conferred with the company's executives, including Disney CEO Bob Iger[42] and studio chairman Alan Horn, the latter of whom referred to the film as a "brand deposit,"[43] a term adopted from Steve Jobs.[44] Together, the executives discussed the studio's potential choices: purchase the script and shut the production down, put the film in turnaround, or co-produce the film themselves.

Iger approved the film and subsequently contacted Tom Hanks to consider playing the role of Walt Disney, which would become the first-ever depiction of Disney in a mainstream film.[2] Hanks accepted the role, viewing it as "an opportunity to play somebody as world-shifting as Picasso or Chaplin".[45] Hanks made several visits to The Walt Disney Family Museum and interviewed some of Disney's former employees and family relatives, including his daughter Diane Disney Miller.[46][47] The film was subsequently dedicated to Disney Miller, who died just before it was released.[48]

In April 2012, Emma Thompson entered final negotiations to star as P. L. Travers, after the studio was unable to secure Meryl Streep for the part.[49] Thompson said that the role was the most difficult one that she has played, describing Travers as "a woman of quite eye-watering complexity and contradiction."[50] "She wrote a very good essay on sadness, because she was, in fact, a very sad woman. She'd had a very rough childhood, the alcoholism of her father being part of it and the attempted suicide of her mother being another part of it. I think that she spent her whole life in a state of fundamental inconsolability and hence got a lot done."[51]

"I thought the script was a fair portrayal of Walt as a mogul but also as an artist and a human being. But I still had concerns that it could be whittled away. I don't think this script could have been developed within the walls of Disney—it had to be developed outside...I'm not going to say there weren't discussions, but the movie we ended up with is the one that was on the page."

With Walt Disney Pictures' backing, the production team was given access to 36 hours of Travers' audio recordings of herself, the Shermans, and co-writer Don DaGradi that were produced during the development of Mary Poppins,[11] in addition to letters written between Disney and Travers from the 1940s through the 1960s.[36][40] Richard Sherman also worked on the film as a technical advisor and shared his side of his experiences working with Travers on Mary Poppins.[11] Initially, director John Lee Hancock had reservations about Disney's involvement with the film, believing that the studio would edit the screenplay in their founder's favor. However, Marcel admitted that the studio "specifically didn't want to come in and sanitize it or change Walt in any way."[36] Although the filmmakers did not receive any creative interference from Disney regarding Walt Disney's depiction, the studio did request that they omit any onscreen inhalation of cigarettes[52] due to the company's policy of not directly depicting smoking in films released under the Disney banner, and to avoid an R-rating from the Motion Picture Association of America.[53][54] Instead, Disney is shown extinguishing a lit cigarette in one scene, and his notorious smoker's cough is heard off-screen several times throughout the film.[53]

Filming

Principal photography began on September 19, 2012.[29][55] Although some filming was originally to be in Queensland, Australia,[31][56] all filming took place in the Southern California area, including the Walt Disney Studios lot in Burbank, Disneyland Park in Anaheim, Big Sky Ranch in Simi Valley, the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden in Arcadia, Universal Studios' Courthouse Square, and the TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood.[56][57] For the Disneyland sequences, scenes were shot during the early morning, with certain areas cordoned off during the park's daily operation, including Sleeping Beauty Castle, Main Street U.S.A., Fantasyland, and the King Arthur Carrousel attractions,[58] while the park's cast members were hired as extras.[59] Production designer Michael Corenblith had to ensure that post-1961 attractions did not show up on camera, and that storefronts on Main Street were redecorated to appear as they did during that time period.[60][61] Corenblith also had to recreate Disney's office, using photographs and a furniture display from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library as references.[40][62] To recreate the original film's premiere at the Chinese Theatre, set designers closed Hollywood Boulevard and redressed the street and theater to resemble their 1964 appearances.[62]

Emma Thompson prepared for her role by studying Travers' own recordings conducted during the development of Mary Poppins, and also styled her natural hair after Travers', due to the actress's disdain for wigs.[63] To accurately convey Walt Disney's midwestern dialect, Tom Hanks listened to archival recordings of Disney in his car and practised the voice while reading newspapers.[64][65] Hanks also grew his own mustache for the role, which underwent heavy scrutiny, with the filmmakers going so far as to match the dimensions of Hanks' mustache to that of Disney.[66][67] Jason Schwartzman and B. J. Novak worked closely with Richard M. Sherman during pre-production and filming. The lyricist described the actors as "perfect talents" for their roles as Richard and Robert B. Sherman.[68] Costume designer Daniel Orlandi had Thompson wear authentic jewelry borrowed from The Walt Disney Family Museum,[69] and ensured that Hanks' wardrobe included the Smoke Tree Ranch emblem from the Palm Springs property embroidered on his neckties, which Disney always wore.[70] The design department also had to recreate several of the costumed Disneyland characters as they appeared in the 1960s.[71] Filming was completed on November 22, 2012.[31][72][73] Walt Disney Animation Studios produced a recreation of the Tinker Bell animation featured in the Walt Disney-hosted weekly TV show Walt Disney Presents.[74]

Historical accuracy

Saving Mr. Banks depicts several events that differ from recorded accounts.[75] The dramatic premise of the script—that Walt Disney had to convince P.L. Travers to hand over the film rights, including the scene when he finally persuades her—is fictionalized, as Disney had already secured the film rights (subject to Travers' approval of the script) when Travers arrived to consult with the Disney staff.[9][10] Disney in fact left Burbank to vacation in Palm Springs, California a few days into Travers' visit to the United States, and was not present at the studio when several of the film's scenes depict him to be in.[11] Therefore, many of the dialogue scenes between Travers and Disney are adapted from letters, telegrams, and telephone correspondence between the two.[11]

The film also depicts Travers coming to amicable terms with Disney, including her approval of his changes to the story.[76] In reality, she never approved of the dilution of the harsher aspects of Mary Poppins' character, felt ambivalent about the music, and hated the use of animation.[77][78] Disney overruled her objections to portions of the final film, citing contract stipulations that he had final cut privilege. After the film's premiere, Travers reportedly approached Disney and told him that the animated sequences had to be removed. Disney dismissed her request, saying, "Pamela, the ship has sailed".[15]

Although the film portrays Travers as being emotionally moved during the premiere of Mary Poppins, presumably due to her feelings about her father,[15] co-screenwriter Kelly Marcel and several critics note that, in real life, Travers was in fact seen crying at the premiere out of anger and frustration over the film,[11][9][15][16] which she felt betrayed the artistic integrity of her characters and work.[17] Resentful at what she considered poor treatment at Disney's hands, Travers vowed to never permit The Walt Disney Company to adapt any of her other novels in any form of media.[18] Travers' last will, in fact, bans any Americans from adapting her works to any form of media.[11] According to the Chicago Tribune, Disney was "indulging in a little revisionist history with an upbeat spin", adding that "the truth was always complicated" and that Travers subsequently viewed the film multiple times.[19]

English writer Brian Sibley found Travers still gun-shy from her experiences with Disney when he was hired to write a possible Mary Poppins sequel in 1980s. Sibley reported that Travers told him, “I could only agree if I could do it on my own terms. I'd have to work with someone I trust.” Nevertheless, while watching the original film together—the first time Travers had seen it since the premiere—she became excited during moments and thought they were excellent, while other parts she considered to be terrible.[79] The sequel never went to production, and when approached to do a stage adaptation in the 1990s, she only acquiesced on the condition that English-born writers and no one from the film production were to be directly involved with the musical's development.[21][22][80]

Although Travers was assigned a limousine driver,[11] the character of Ralph is fictionalized and intended to be an amalgamation of the studio's drivers.[81] In real life, Disney story editor Bill Dover was assigned as Travers' guide and companion during her time in Los Angeles.[11]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

The film's original score was composed by Thomas Newman.[82] Newman's process of scoring the film included playing themes to filmed scenes, so that he could "listen to what the music does to an image."[83] Walt Disney Records released two editions of the soundtrack on December 10, 2013: a single-disc and a two-disc digipak deluxe edition (containing original demo recordings by the Sherman Brothers and selected songs from Mary Poppins).[84][85]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Chim Chim Cher-ee (East Wind)" | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | Colin Farrell | 1:04 |

| 2. | "Travers Goff" | Thomas Newman | 2:06 | |

| 3. | "Walking Bus" | Thomas Newman | 2:10 | |

| 4. | "One Mint Julep" | Rudy Toombs | Ray Charles | 1:31 |

| 5. | "Uncle Albert" | Thomas Newman | 1:34 | |

| 6. | "Jollification" | Thomas Newman | 1:18 | |

| 7. | "The Mouse" | Thomas Newman | 0:57 | |

| 8. | "Leisurely Stroll" | Thomas Newman | 1:34 | |

| 9. | "Chim Chim Cher-ee (Responstible)" | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | Jason Schwartzman, B. J. Novak, and Emma Thompson | 0:26 |

| 10. | "Mr. Disney" | Thomas Newman | 0:35 | |

| 11. | "Celtic Soul" | Thomas Newman | 1:20 | |

| 12. | "A Foul Fowl" | Thomas Newman | 2:04 | |

| 13. | "Mrs. P. L. Travers" | Thomas Newman | 1:16 | |

| 14. | "Laying Eggs" | Thomas Newman | 1:08 | |

| 15. | "Worn to Tissue" | Thomas Newman | 0:54 | |

| 16. | "Heigh-Ho" | Frank Churchill, Larry Morey | The Dave Brubeck Quartet | 2:11 |

| 17. | "Whiskey" | Thomas Newman | 1:21 | |

| 18. | "Impertinent Man" | Thomas Newman | 0:38 | |

| 19. | "To My Mother" | Thomas Newman | 3:44 | |

| 20. | "Westerly Weather" | Thomas Newman | 1:58 | |

| 21. | "Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious" | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | Jason Schwartzman, B. J. Novak, and Emma Thompson | 0:05 |

| 22. | "Spit Spot!" | Thomas Newman | 1:49 | |

| 23. | "Beverly Hills Hotel" | Thomas Newman | 0:38 | |

| 24. | "Penguins" | Thomas Newman | 1:18 | |

| 25. | "Pears" | Thomas Newman | 0:55 | |

| 26. | "Let's Go Fly a Kite" | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | Jason Schwartzman, B. J. Novak, Bradley Whitford, Melanie Paxson, and Emma Thompson | 1:55 |

| 27. | "Maypole" | Thomas Newman | 0:59 | |

| 28. | "Forgiveness" | Thomas Newman | 2:00 | |

| 29. | "The Magic Kingdom" | Thomas Newman | 1:05 | |

| 30. | "Ginty My Love" | Thomas Newman | 3:12 | |

| 31. | "Saving Mr. Banks (End Title)" | Thomas Newman | 2:12 | |

| Total length: | 45:57 | |||

All tracks are written by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman

| No. | Title | Artist(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Pearly Song" (Demo) | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | 1:30 |

| 2. | "Chim Chim Cher-ee" (Demo) | Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman | 2:39 |

| 3. | "Tuppence a Bag" (Demo) | Richard M. Sherman | 2:55 |

| 4. | "Let's Go Fly a Kite" (Demo) | Richard M. Sherman | 1:44 |

| 5. | "A Spoonful of Sugar" | Julie Andrews | 4:07 |

| 6. | "Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious" | Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke | 2:02 |

| 7. | "Chim Chim Cher-ee" | Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, Karen Dotrice, and Matthew Garber | 2:46 |

| 8. | "Feed the Birds" | Julie Andrews | 3:50 |

| 9. | "Let's Go Fly a Kite" | David Tomlinson, Dick Van Dyke, and the Londoners | 1:48 |

| Total length: | 23:21 | ||

Release

A trailer for the film was released on July 10, 2013.[86]

Saving Mr. Banks held its world premiere at the London Film Festival on October 20, 2013.[87][88][89] On November 7, 2013, Walt Disney Pictures held the film's U.S. premiere at the TCL Chinese Theatre during the opening night of the 2013 AFI Film Festival,[90][91] the same location where Mary Poppins premiered.[92] The original film was also screened for its 50th anniversary.[93] Saving Mr. Banks also served as the Gala Presentation at the 2013 Napa Valley Film Festival on November 13,[94] and was screened at the AARP Film Festival in Los Angeles on November 17,[42] as Disney heavily campaigned Saving Mr. Banks for Academy Awards consideration.[42] On December 9, 2013, the film was given an exclusive corporate premiere in the Main Theater of the Walt Disney Studios lot in Burbank.[95] The film was released in the United States on December 13, 2013, in limited release, and in wide release on December 20.[96] Despite not earning a nomination, the film was widely considered by pundits to be a front-runner for Best Picture at the 86th Academy Awards.[97][98][99][100][101]

Home media

Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment released Saving Mr. Banks on Blu-ray Disc, DVD, and digital download on March 18, 2014.[102] The film debuted at No. 2 in Blu-ray and DVD sales in the United States according to Nielsen's sales chart.[103]

Reception

Box office

Saving Mr. Banks grossed $18.1 million in its opening domestic weekend.[104] By the end of its theatrical run, Saving Mr. Banks earned $83.3 million in North America, and $29.2 million in other countries for a worldwide total of $112,544,580.[3]

Critical response

Saving Mr. Banks received positive reviews from film critics, with major praise directed to the acting; particularly Emma Thompson, Tom Hanks, and Colin Farrell's performances, especially reserved to Thompson.[42][105][106] Film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports an 79% "Certified Fresh" approval rating from critics, based on 225 reviews with an average score of 7/10. The site's consensus reads: "Aggressively likable and sentimental to a fault, Saving Mr. Banks pays tribute to the Disney legacy with excellent performances and sweet, high-spirited charm."[107] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 65 (out of 100) based on 46 reviews from mainstream critics, considered to be "generally favorable".[108]

The Hollywood Reporter praised the film as an "affecting if somewhat soft-soaped comedy drama, elevated by excellent performances." The Reporter wrote that "Emma Thompson takes charge of the central role of P. L. Travers with an authority that makes you wonder how anybody else could ever have been considered."[109] Scott Foundas of Variety wrote that the film "has all the makings of an irresistible backstage tale, and it’s been brought to the screen with a surplus of old-fashioned Disney showmanship...", and that Tom Hanks's portrayal captured Walt Disney's "folksy charisma and canny powers of persuasion — at once father, confessor and the shrewdest of businessmen." Overall, he praised the film as "very rich in its sense of creative people and their spirit of self-reinvention."[110]

The Washington Post rated the film three out of four stars, writing: "Saving Mr. Banks doesn't always straddle its stories and time periods with the utmost grace. But the film — which John Lee Hancock directed from a script by Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith — more than makes up for its occasionally unwieldy structure in telling a fascinating and ultimately deeply affecting story, along the way giving viewers tantalizing glimpses of the beloved 1964 movie musical, in both its creation and final form."[111] The New York Times' A. O. Scott gave a positive review, declaring the film as "an embellished, tidied-up but nonetheless reasonably authentic glimpse of the Disney entertainment machine at work."[112]

Mark Kermode awarded the film four out of five stars, lauding Thompson's performance as "impeccable", elaborating that "Thompson dances her way through Travers' conflicting emotions, giving us a fully rounded portrait of a person who is hard to like but impossible not to love."[113] Michael Phillips felt similarly, writing: "Thompson's the show. Each withering put-down, every jaundiced utterance, lands with a little ping." In regard to the screenplay, he wrote that "screenwriters Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith treat everyone gently and with the utmost respect."[114] Peter Travers also gave the film three out of four stars and equally commended the performances of the cast.[115]

Alonso Duralde described the film as a "whimsical, moving and occasionally insightful tale ... director John Lee Hancock luxuriates in the period detail of early-’60s Disney-ana".[116] Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "B+" grade, explaining that "the trick here is how perfectly Thompson and Hanks portray the gradual thaw in their characters' frosty alliance, empathizing with each other's equally miserable upbringings in a beautiful three-hankie scene late in the film."[117] Kenneth Turan of The Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "does not strictly hew to the historical record where the eventual resolution of this conflict is concerned," but admitted that it "is easy to accept this fictionalizing as part of the price to be paid for Thompson's engaging performance."[118]

David Gritten of The Daily Telegraph described the confrontational interaction between Thompson and Hanks as "terrific", singling out Thompson's "bravura performance", and calling the film itself "smart, witty entertainment".[119] Kate Muir of The Times spoke highly of Thompson and Hanks's performances.[120] Joe Morgenstern of The Wall Street Journal, however, considered Colin Farrell to be the film's "standout performance".[121] IndieWire's Ashley Clark wrote that the film "is witty, well-crafted and well-performed mainstream entertainment which, perhaps unavoidably, cleaves to a well-worn Disney template stating that all problems—however psychologically deep-rooted—can be overcome."[122] Another staff writer labeled Thompson's performance as her best since Sense and Sensibility, and stated that "she makes the Australian-born British transplant a curmudgeonly delight."[123] Peter Bradshaw enjoyed Hanks' role as Disney, suggesting that, despite its brevity, the film would have been largely "bland" without it.[124]

The film did receive some criticism. The Independent gave the film a mixed review, writing: "On the one hand, Saving Mr. Banks (which was developed by BBC Films and has a British producer) is a probing, insightful character study with a very dark undertow. On the other, it is a cheery, upbeat marketing exercise in which the Disney organization is re-promoting one of its most popular film characters."[125] David Sexton of the Evening Standard concluded that the film "is nothing but a big corporation boasting about its own marvellousness."[126] Lou Lumenick of The New York Post criticized the accuracy of the film's events, concluding that "Saving Mr. Banks is ultimately much less about magic than making the sale, in more ways than one."[127] American history lecturer John Wills praised the film's attention to detail, such as the inclusion of Travers' original recordings, but doubted that the interpersonal relations between Travers and Disney were as amicable as portrayed in the film.[128] Film School Rejects also described several moments where the film had a "shrewd consumption of [the company's] own criticisms", only to later negate them and Disney-fy Travers as a character.[17]

Saving Mr. Banks was named the sixth best film of 2013 by Access Hollywood.[129]

Accolades

| Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

| AARP Annual Movies for Grownups Awards[130] | January 6, 2014 | Best Movie for Grownups Who Refuse to Grow Up | Saving Mr. Banks | Won |

| Academy Awards | March 2, 2014 | Best Original Score | Thomas Newman | Nominated |

| African-American Film Critics Association[131] | December 13, 2013 | Best Film of the Year | 8th place | |

| Alliance of Women Film Journalists[132] | December 19, 2013 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| American Cinema Editors[133] | February 7, 2014 | Best Edited Feature Film - Dramatic | Mark Livolsi | Nominated |

| American Film Institute[134] | January 10, 2014 | Top Ten Films of the Year | Alison Owen, Ian Collie, and Philip Steuer | Won |

| Art Directors Guild[135] | February 8, 2014 | Excellence in Production Design - Period Film | Michael Corenblith | Nominated |

| Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Awards[136] | January 10, 2014 | Best Screenplay – International | Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith | Nominated |

| British Academy of Film and Television Arts[137] | February 16, 2014 | Outstanding British Film | Alison Owen, Ian Collie, and Philip Steuer | Nominated |

| Best Actress in a Leading Role | Emma Thompson | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer | Kelly Marcel | Nominated | ||

| Best Film Music | Thomas Newman | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Daniel Orlandi | Nominated | ||

| Broadcast Film Critics Association[138] | January 16, 2014 | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated | ||

| Best Score | Thomas Newman | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Daniel Orlandi | Nominated | ||

| Costume Designers Guild[139] | February 22, 2014 | Excellence in Period Film | Daniel Orlandi | Nominated |

| Denver Film Critics Society[140] | January 13, 2014 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| Empire Awards[141][142] | March 30, 2014 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards[143] | January 12, 2014 | Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| Houston Film Critics Society[144] | December 15, 2013 | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Score | Thomas Newman | Nominated | ||

| Las Vegas Film Critics Society[145] | December 18, 2013 | Top Ten Films | 7th place | |

| Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Won | ||

| Best Family Film | Won | |||

| Location Managers Guild of America[146] | March 29, 2014 | Outstanding Achievement by a Location Professional – Feature Film | Andrew Ullman and Lori Balton | Nominated |

| London Film Critics Circle[147] | February 2, 2014 | Supporting Actor of the Year | Tom Hanks | Nominated |

| British Actress of the Year | Emma Thompson (also for Beautiful Creatures) | Nominated | ||

| National Board of Review[148] | December 4, 2013 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Won |

| Top Ten Films | Saving Mr. Banks | Won | ||

| Palm Springs International Film Festival[149] | January 5, 2014 | Creative Impact in Directing Award | John Lee Hancock | Won |

| Phoenix Film Critics Society[150] | December 17, 2013 | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Director | John Lee Hancock | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress in a Leading Role | Emma Thompson | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Tom Hanks | Nominated | ||

| Best Ensemble Acting | Nominated | |||

| Best Original Score | Thomas Newman | Nominated | ||

| Best Production Design | Lauren E. Polizzi, Michael Corenblith | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Daniel Orlandi | Nominated | ||

| Best Performance by a Youth in a Lead or Supporting Role – Female | Annie Rose Buckley | Nominated | ||

| Producers Guild of America Award[151] | January 19, 2014 | Best Theatrical Motion Picture | Ian Collie, Alison Owen, Philip Steuer | Nominated |

| San Diego Film Critics Society[152] | December 11, 2013 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| Best Production Design | Michael Corenblith | Nominated | ||

| Satellite Awards[153] | February 23, 2014 | Best Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Actress – Motion Picture | Emma Thompson | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Tom Hanks | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Screenplay | Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction and Production Design | Lauren E. Polizzi and Michael Corenblith | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Daniel Orlandi | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Awards[154][155] | June 18, 2014 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| Society of Camera Operators[156] | March 8, 2014 | Camera Operator of the Year Award | Ian Fox | Nominated |

| Screen Actors Guild Awards[157] | January 18, 2014 | Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| St. Louis Gateway Film Critics Association[158] | December 16, 2013 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| Best Original Screenplay | Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith | Nominated | ||

| Best Musical Score | Thomas Newman | Nominated | ||

| UK Regional Critics' Film Awards[159][160] | January 29, 2014 | Best On-Screen Duo | Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks | Won |

| Washington D.C. Area Film Critics Association[161] | December 9, 2013 | Best Actress | Emma Thompson | Nominated |

| Best Score | Thomas Newman | Nominated | ||

| Women in Film and TV Awards[162] | December 5, 2013 | FremantleMedia U.K. New Talent Award | Kelly Marcel (screenwriter of Saving Mr. Banks and Fifty Shades of Grey) | Won |

References

- ^ "SAVING MR. BANKS (PG)". Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. British Board of Film Classification. September 18, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c Barnes, Brooks (October 16, 2013). "Forget the Spoonful of Sugar: It's Uncle Walt, Uncensored". The New York Times. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ a b "Saving Mr. Banks (2013)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "BBC Films unveils upcoming slate at Cannes". BBC. BBC Films. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Cunningham, Todd (December 19, 2013). "'American Hustle' and 'Saving Mr. Banks' Face Mainstream Box-Office Exams This Weekend". The Wrap. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Gettell, Oliver (December 18, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' director: 'Such an advantage' shooting in L.A." The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy (February 12, 2014). "Tom Hanks Tops Our List Of The Most Trustworthy Celebrities". Forbes. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (January 3, 2014). "Does 'Saving Mr. Banks' contain a hidden agenda?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Marama Whyte (January 10, 2014). "Nine 'Mary Poppins' facts 'Saving Mr. Banks' did not get right". Hypable. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Sabina Ibarra (December 12, 2013). "Interview: 'Saving Mr. Banks' Screenwriter Kelly Marcel". Screensave.com. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Goldsmith, Jeff (December 24, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks Q&A" (Podcast). Unlikely Films, Inc. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (December 28, 2013). "Is 'Saving Mr. Banks' too hard on 'Mary Poppins' creator? http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/la-et-mn-disney-mary-poppins-saving-mr-banks-travers-20131228,0,5785246.story#ixzz2vJbKYAK0". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

{{cite news}}: External link in|title= - ^ Mandell, Andrea (December 10, 2013). "Tom Hanks, Emma Thompson duel in 'Saving Mr. Banks'". USA Today. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Newman, Melinda (November 7, 2013). "'Poppins' Author a Pill No Spoonful of Sugar Could Sweeten". Variety. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Lyons, Margaret (December 26, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks Left Out an Awful Lot About P.L. Travers". Vulture. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Caitlin Flanagan (December 19, 2005). "BECOMING MARY POPPINS". Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c Landon Palmer (December 24, 2013). "Landon Palmer Saving Mr. Disney: The Conflicting Arts of Adaptation and Brand Management". Film School Rejects. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Nance, Kevin (December 20, 2013). "Valerie Lawson talks 'Mary Poppins, She Wrote' and P.L Travers". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Jones, Chris (December 20, 2013). "With 'Mary Poppins,' there's more to know under the umbrella". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

In fact, Travers went to see "Mary Poppins" plenty of times after that premiere, so maybe there is some truth to the screenplay. The only person who could verify that died in 1996

- ^ Vincent Dowd (October 20, 2013). "Mary Poppins: Brian Sibley's sequel that never was". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Gettell, Oliver (December 19, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' cast on Walt Disney and P.L. Travers' clashes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Ouzounian, Richard (December 13, 2013). "P.L. Travers might have liked Mary Poppins onstage". The Toronto Star. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ KELLY KONDA. "Is Saving Mr. Banks Just Disney Propaganda? If So, Does It Matter?". Weminoredinfilm.com. paperblog.com. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 12, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks: When Movies Lie and Make You Cry". Time. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (July 10, 2013). "Exclusive First Look: Tom Hanks and Emma Thompson in Saving Mr. Banks". Time. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ Kit, Borys (June 15, 2012). "Colin Farrell in Talks for 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (July 12, 2012). "Bradley Whitford in talks for 'Mr. Banks': Tom Hanks, Emma Thompson star in Disney pic". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Kit, Borys (September 19, 2012). "Rachel Griffiths, Kathy Baker Join 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b "ScreenRant". screenrant.com. Retrieved July 26, 2012. Cite error: The named reference "screenrant" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "chicagotribune". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Production Begins on SAVING MR. BANKS". collider.com. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Kit, Borys (July 31, 2012). "B.J. Novak Joins Disney's 'Saving Mr. Banks' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Forgotten Disney Heroes: The Disney Secretaries". mouseplanet.com. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Jones, J.R. "Film Search: Saving Mr. Banks". Chicago Reader. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Farley, Christopher John (February 11, 2013). "Julie Andrews Talks Poppins and Princesses". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c Shaw, Lucas (December 17, 2013). "How 'Saving Mr. Banks' Overcame Disney's Resistance to a Movie About Disney". The Wrap. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Pond, Steve (December 17, 2013). "Director John Lee Hancock on 'Saving Mr. Banks': We Went for the Truth, Not the Facts". The Wrap. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ http://www.slashfilm.com/interview-kelly-marcel-on-writing-saving-mr-banks/

- ^ Sherman, Robert B. "Tween Pavement and Stars" ("No Red In London") in Moose: Chapters From My Life, AuthorHouse Publishing, Bloomington, IN, p. 372-375.

- ^ a b c d e Kilday, Gregg (December 16, 2013). "Bringing Walt Disney (and Mary Poppins) Back to Life: The Making of 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Child, Ben (April 11, 2012). "Guardian". London: www.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Hilary (October 28, 2013). "AARP Film Festival to Include 'August: Osage County,' 'Saving Mr. Banks' and 'Labor Day'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ Lang, Brent (April 17, 2013). "CinemaCon: Disney Promises More 'Star Wars,' 'Pirates of the Caribbean'". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Chmielewski, Dawn C. (October 6, 2011). "Steve Jobs brought his magic to Disney". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Palmer, Martyn (September 28, 2013). "'I still get to make fantastic films - and that's perplexing to me': Tom Hanks on guns, God... and hanging out with The Beatles". Daily Mail UK. London. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ Riefe, Jordan (October 18, 2012). "Tom Hanks on Becoming Walt Disney for 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ Kaufman, Amy (November 8, 2013). "AFI Fest 2013: Tom Hanks back in spotlight for 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Jay Weston (December 9, 2013). "Tom Hanks IS Walt Disney in "Saving Mr. Banks"!". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (April 9, 2012). "Tom Hanks Now Getting Serious For 'Saving Mr. Banks'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (July 10, 2013). "Exclusive First Look: Tom Hanks and Emma Thompson in Saving Mr. Banks". Time. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Hilary (November 16, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' Star Emma Thompson Shares P. L. Travers Insights, Favorite Films". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Buerger, Megan (December 12, 2013). "Why 'Saving Mr. Banks' Didn't Save Walt Disney From Smoking". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ a b McClintock, Pamela (November 16, 2013). "Disney's Smoking Ban Means No Puffing for Walt Disney in 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Sacks, Ethan (December 8, 2013). "Tom Hanks goes toe-to-toe with Emma Thompson in 'Saving Mr. Banks'". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Disney Starts Production on Saving Mr. Banks". ComingSoon.net. September 19, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Saving Mr Banks begins filming in LA, Rachel Griffiths joins cast". if.com.au. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Schmidt, Chuck (March 29, 2013). "Tom Hanks plays Walt Disney in 'Saving Mr. Banks,' due in theaters Dec. 20". Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ Tully, Sarah (November 7, 2012). "Tom Hanks as Walt Disney closes parts of Disneyland". The Orange County Register. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ Tully, Sarah (October 24, 2012). "Tom Hanks' movie to film at Disneyland". The Orange County Register. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ Rich, Katey (December 11, 2013). "Exclusive Video: How The Saving Mr. Banks Team Re-Created 1960s Disneyland". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ "What It Was Like Turning Modern Day Disneyland Into Walt's 1961 Magic Kingdom". The Walt Disney Company. Disney D23. December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Verrier, Richard (December 18, 2013). "For 'Mr. Banks,' Simi Valley works as Australian outback". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Setoodeh, Ramin (November 19, 2013). "How 'Saving Mr. Banks' Saved Emma Thompson". Variety. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Mandell, Andrea (November 8, 2013). "Tom Hanks read newspapers in Walt Disney's voice". USA Today. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Pearce, Garth (November 2, 2013). "Oscar winner Emma Thompson reveals why Saving Mr Banks role is right up her street". Daily Express. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Rechtshaffen, Michael (December 6, 2013). "Tom Hanks works Disney magic in 'Saving Mr. Banks'". Toronto Sun. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ Spero, Jesse (November 11, 2013). "Tom Hanks Talks Walt Disney Transformation For Saving Mr. Banks". Access Hollywood. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ King, Susan (November 1, 2013). "Sherman brothers of 'Saving Mr. Banks' get in tune with a real one". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ Kinosian, Janet (December 5, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' costume designer Daniel Orlandi digs deep". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Ross, L.A. (December 20, 2013). "TheWrap Screening Series: Recreating Disney's World for 'Saving Mr. Banks'". The Wrap. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Julie (December 19, 2013). "From Sketch to Still: Recreating Vintage Disney for Saving Mr. Banks". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Lussier, Germaine. "Marvel and Disney Release Info: 'Ant-Man' Gets Official Release Date, 'Iron Man 3′ and 'Thor: The Dark World' Will Be 3D". /Film. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Minovitz, Ethan (September 21, 2012). "Saving Mr. Banks Tells Story Behind Mary Poppins Adaptation". Big Cartoon News. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ Hill, Jim (January 2, 2014). ""Saving Mr. Banks" production team works with Disney Archives to accurately recreate Walt's World circa 1962". Jim Hill Media. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (January 3, 2014). "Does 'Saving Mr. Banks' contain a hidden agenda?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (December 28, 2013). "Is 'Saving Mr. Banks' too hard on 'Mary Poppins' creator? http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/la-et-mn-disney-mary-poppins-saving-mr-banks-travers-20131228,0,5785246.story#ixzz2vJbKYAK0". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

{{cite news}}: External link in|title= - ^ Mandell, Andrea (December 10, 2013). "Tom Hanks, Emma Thompson duel in 'Saving Mr. Banks'". USA Today. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Newman, Melinda (November 7, 2013). "'Poppins' Author a Pill No Spoonful of Sugar Could Sweeten". Variety. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Vincent Dowd (October 20, 2013). "Mary Poppins: Brian Sibley's sequel that never was". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ KELLY KONDA. "Is Saving Mr. Banks Just Disney Propaganda? If So, Does It Matter?". Weminoredinfilm.com. paperblog.com. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 12, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks: When Movies Lie and Make You Cry". Time. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Thomas Newman Scoring 'Saving Mr. Banks'". Film Music Reporter. April 25, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (February 28, 2014). "Oscars: John Williams, Jill Scott Spotlight Song and Score Nominees at Academy's First-Ever Concert". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "Walt Disney Records Presents Saving Mr. Banks Original Motion Picture Score Soundtrack And Saving Mr. Banks 2-Disc Deluxe Edition Soundtrack Features Previously Unreleased Song Demos By The Sherman Brothers Both Available On December 10". PR Newswire. November 26, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (November 7, 2013). "Watch: New Clip, 2 Featurettes & Complete Details On 2-Disc Soundtrack For 'Saving Mr. Banks'". IndieWire. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (July 11, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' Trailer: Tom Hanks as Walt Disney in 'Mary Poppins' Biopic". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (October 20, 2013). "Tom Hanks Starrer 'Saving Mr. Banks' Closes BFI London Film Festival". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (August 8, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' to Close London Film Fest". Variety. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Szalai, Georg (August 8, 2013). "Disney's 'Saving Mr. Banks' to Close BFI London Film Festival". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (September 4, 2013). "AFI Fest Selects Disney's 'Saving Mr Banks', Bennett Miller's 'Foxcatcher' For Opening Slots". Deadline. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (September 4, 2013). "Tom Hanks' 'Saving Mr. Banks' to Open AFI Fest". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Borys Kit; Scott Feinberg (November 9, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' Adds to Momentum at Sing-Along with 'Mary Poppins' Legend". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Pond, Steve (October 22, 2013). "AFI Fest Adds Oscar Foreign Contenders, Eli Roth, 'Mary Poppins'". The Wrap. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (September 19, 2013). "'August: Osage County', 'Saving Mr. Banks' Heading to Napa Valley Film Festival". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (December 10, 2013). "Julie Andrews And Dick Van Dyke Light Up 'Saving Mr. Banks' Premiere As Disney Goes All Interactive With 'Mary Poppins' (Exclusive)". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Schillaci, Sophie; Pamela McClintock (June 13, 2013). "Disney Dates Musical 'Into the Woods' Opposite 'Annie' in December 2014". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (November 8, 2013). "AFI Fest: 'Saving Mr. Banks' Aims to Become Third Consecutive Movie About Hollywood to Win Top Oscar". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (November 8, 2013). "AFI Fest: A "Practically Perfect" U.S. Premiere For Disney's 'Saving Mr. Banks' Steps Up Oscar Talk". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Stone, Sasha (November 8, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks, Emma Thompson, Tom Hanks Launch into the Oscar race". Awards Daily. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Tim, Gray (November 8, 2013). "Cheers, Tears and Awards Buzz for the 3-Hankie 'Banks'". Variety. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ Whipp, Glenn (December 5, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' and 'Nebraska' are safe bets for Oscar nods". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Murray, Noel (March 15, 2014). "New releases: Disney's Oscar-winning heartwarmer 'Frozen'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ Arnold, Thomas K. (March 26, 2014). "'Frozen' Easily Tops Home Video Sales Charts". Variety. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?view=&yr=2013&wknd=51&p=.htm

- ^ Rosen, Christopher (October 20, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' Reviews Are Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ Salazar, Francisco (October 21, 2013). "Oscar Hopeful 'Saving Mr. Banks' Makes World Premiere To Good Reviews". Latinos Post. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Saving Mr. Banks". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ "Saving Mr. Banks". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (October 20, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks: London Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (October 20, 2013). "Film Review: 'Saving Mr. Banks'". Variety. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Hornaday,, Ann (December 12, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' review: The affecting story of how 'Mary Poppins' reached the screen". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Scott, A.O. (December 12, 2013). "An Unbeliever in Disney World". The New York Times. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Kermode, Mark (November 30, 2013). "Saving Mr Banks – review". The Observer. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ Phillips, Michael (December 12, 2013). "Review: 'Saving Mr. Banks'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 12, 2013). "Saving Mr. Banks: Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Duralde, Alonso (November 6, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' Review: Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks Are Spit-Spot-On in This Hollywood Valentine". The Wrap. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (December 11, 2013). "Movie Review: Saving Mr. Banks". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (December 12, 2013). "Review: Emma Thompson is a ripsnorter in 'Saving Mr. Banks'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Gritten, David (October 20, 2013). "Saving Mr Banks, first review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Muir, Kate (October 21, 2013). "Saving Mr Banks, London Film Festival". The Times. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Morgenstern, Joe (December 12, 2013). "Review: Saving Mr. Banks". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Clark, Ashley (October 20, 2013). "Review: 'Saving Mr. Banks,' With Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks, Puts an Enjoyable Spin On the 'Mary Poppins' Saga Without Romanticizing Disney". Indie Wire. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ Mueller, Matt (November 8, 2013). "Review: Thompson Triumphs in 'Saving Mr. Banks,' which Adds Spoonful of Sugar to Backstage 'Mary Poppins' Tale (TRAILER)". Thompson on Hollywood. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (October 20, 2013). "Saving Mr Banks: London film festival – first look review". The Guardian. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (November 28, 2013). "Saving Mr Banks: Film review - a sugar coated, disingenuous marketing exercise for Disney". The Independent. London. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Sexton, David (November 29, 2013). "Saving Mr Banks - film review". Evening Standard. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Lumenick, Lou (December 10, 2013). "'Saving Mr. Banks' more like 'Selling Mary Poppins'". The New York Post. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "Historian at the Movies: Saving Mr. Banks reviewed". historyextra.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Mantz, Scott (November 14, 2013). "Top 13 Movies Of 2013 (MovieMantz)". Access Hollywood. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "AARP Names '12 Years a Slave' Best Movie for Grownups". AFI. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "African American Film Critics Name 12 Years a Slave Best Picture of the Year". Awards Daily. December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "2013 EDA Award Nominess". Alliance of Women Film Journalists. December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (January 10, 2014). "'12 Years a Slave,' 'Captain Phillips,' 'Gravity' Among ACE Eddie Award Nominees". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2013". American Film Institute. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Art Directors Guild Nominations Announced". The Hollywood Reporter. January 9, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Australian Academy announces nominees for 3rd AACTA International Awards" (PDF). Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA). December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (January 7, 2014). "Battle for BAFTAs: 'Gravity,' '12 Years,' 'Hustle,' 'Phillips' in Kudos Fight". Variety. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Tim (December 16, 2013). "Critics Choice Awards: '12 Years,' 'American Hustle' Earn 13 Nominations Each". Variety. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ "Costume Designers Guild Unveils Awards Nominations". The Hollywood Reporter. January 8, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ "Denver Film Critics Society Nominations". Awards Daily. December 6, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "The Jameson Empire Awards 2014 Nominations Are Here!". Empire. February 24, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "Jameson Empire Awards 2014: The Winners". Empire. March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ "Golden Globe Awards Nominations: '12 Years A Slave' & 'American Hustle' Lead Pack". Deadline. December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ "12 Years a Slave wins Pic, Cuaron Director for Houston Film Critics". Awards Daily. December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "2013 Las Vegas Film Critics' Society Award winners". Hitfix. December 18, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Location Managers Unveil Inaugural Awards Nominees". Deadline.com. February 27, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "2013 London Film Critics' Circle Award nominations". HitFix. December 17, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ "National Board of Review Chooses 'Her' as Best Film, Will Forte and Octavia Spencer Land Wins". The Awards Circuit. December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ Fessier, Bruce (December 3, 2013). "Variety to honor John Lee Hancock and Jonah Hill at Palm Spring Film Festival". The Desert Sun. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ "Phoenix Film Critics Society 2013 Award Nominations". Phoenix Film Critics Society. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Pond, Steve (January 2, 2014). "Producers Guild Nominations: 'Wolf of Wall Street,' 'Blue Jasmine' Make the Cut". The Wrap. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (December 11, 2013). "2013 San Diego Film Critics Society winners". HitFix. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (December 2, 2013). "Satellite Awards: '12 Years a Slave' Leads Film Nominees". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (February 26, 2014). "Saturn Award Nominations Announced; GRAVITY and THE HOBBIT: THE DESOLATION OF SMAUG Lead with 8 Nominations Each". Collider. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ ""Gravity" and "The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug" soar with eight nominations, "The Hunger Games: Catching Fire," scored 7, "Iron Man 3," "Pacific Rim," "Star Trek Into Darkness and Thor: The Dark World lead with five nominations apiece for the 40th Annual Saturn Awards, while "Breaking Bad," "Falling Skies," and "Game of Thrones" lead on television in an Epic Year for Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror". Saturn Awards. February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Nominations Announced for Annual Society of Camera Operators Awards for Camera Operator of the Year -- Feature Film and Television". PRNewswire. January 9, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ "Nominations Announced for the 20th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards®". December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Stone, Sasha (December 9, 2013). "The St. Louis Film Critics Nominations". Awards Daily. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (January 29, 2014). "'12 Years a Slave' tops UK Regional Critics' vote". HitFix. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ Passmore, Joseph (January 30, 2014). "Slave, Gravity win at Regional Critics Awards". ScreenDaily. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ Stone, Sasha (December 7, 2013). "Washington DC Film Critics Announce Nominations". Awards Daily. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (December 5, 2013). "'Fifty Shades' Screenwriter Kelly Marcel Among Women in Film, TV Award Winners in London". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

External links

- Official website at Disney.com

- Saving Mr. Banks at IMDb

- Saving Mr. Banks at History vs. Hollywood

- Saving Mr. Banks at the TCM Movie Database

- Saving Mr. Banks at Box Office Mojo

- Saving Mr. Banks at Rotten Tomatoes

- Saving Mr. Banks at Metacritic

- Saving Mr. Banks at BBC Online

- 2013 films

- 2010s biographical films

- 2010s comedy-drama films

- English-language films

- American biographical films

- American comedy-drama films

- British biographical films

- British comedy-drama films

- Australian biographical films

- Australian comedy-drama films

- BBC Films films

- Biographical films about writers

- Comedy films based on actual events

- Disneyland

- Drama films based on actual events

- Films about alcoholism

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about film directors and producers

- Films about films

- Films about filmmaking

- Films about Disney

- Films directed by John Lee Hancock

- Film scores by Thomas Newman

- Films set in 1906

- Films set in 1961

- Films set in 1964

- Films set in amusement parks

- Films set in country houses

- Films set in hotels

- Films set in a movie theatre

- Films set in studio lots

- Films set in London

- Films set in Los Angeles, California

- Films set in Queensland

- Films shot in Los Angeles, California

- Mary Poppins

- Nonlinear narrative films

- Sherman Brothers

- Walt Disney

- Walt Disney Pictures films