Access to medicines

Access to medicines refers to the reasonable ability for people to get needed medicines required to achieve health.[1] Such access is deemed to be part of the right to health as supported by international law since 1946.[2]

The World Health Organization states that essential medicines should be available, of good quality, and accessible.[2] Reasonable access to medicines can be in conflict with intellectual property and free markets.[3] In the developing world people may not get treatment for conditions like HIV/AIDS.[4]

Factors that Block Medication Access

Patent Protection & Market Exclusivity

Patents provide a owner exclusive rights to a product or process for 20 years in a particular territory. The owner of the patent has the right to prevent the manufacture, use, sell, import, or distribution of the patented product[5]. It is argued that patent protection allows pharmaceutical companies a monopoly on particular drugs and processes[6][7].

Data Exclusivity

Data exclusivity is a regulatory measure limiting the use of clinical trial data and provides conductor of the trial temporary exclusive rights to the data[6]. Many suggest that extending exclusivity periods can have consequences in delivering medication, especially generic brands, to developing countries. However, extending patent terms can be reinvested for research and development and/or a source of funding for drug donations to low-income countries[8]. Others suggest that data exclusivity works to diminish the availability of generic drugs. Many argue that pharmaceutical companies push for data exclusivity--seeking to extend their monopolies by advocating for market exclusivity provided by patents and data exclusivity, or protection for new medicine[6].

Cost

Due to factors such as market exclusivity and data exclusivity, a pharmaceutical company ultimately have control of the pricing of their patented product. Therefore, the owner also has control of the pricing of the medication, based on the price level the owner deems best to reflects their ability to manufacture and the level of profit desired. Purchasers have little say over the price set[9]. It is argued that competition from generic brands is necessary to lower drug prices and improve access to affordable medications[10][11].

Daraprim price hike

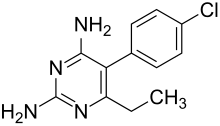

On August 10, 2015, Turig Pharmaceuticals, a pharmaceutical company owned by Martin Shkreli, purchased the rights to a Daraprim[12]. Daraprim, an anti-parastic and anti-malarial drug, is considered a essential drug for HIV treatments. It is widely used to treat patients with AIDS-related and AIDs-unrelated toxoplasmosis.[13] At the time, no other generic versions of the drug was available. Turig dramatically raised the price of the drug from $13.50 a tablet to $750, a 5000% increase[14].

Availability of Generic Brands

Many argue that generic brand production in developing countries are essential to bridge the global drug gap[11][9]. As argued by various sources, the push for more measures such as market and data exclusivity, hinders low-income countries’ ability to to manufacture and produce generic drugs[6]. However, low-income countries often lack the essential infrastructure to allow for generic brand production[9][8]. In order the use of the medication to be effective, it must be manufactured in optimal laboratory conditions. Developing countries often lack air conditioning, stable electrical power, or refrigerators to store samples and chemicals[8]. It also argued that that international aid, state investment, and measures for infection prevention are necessary to allow for generic brand production in low-income countries[9].

HIV/AIDS Crisis

The appearance of generic manufacturers in low-income countries, such as India and Brazil, was key to increasing access to HIV/AIDS treatment in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs). Due to the introduction of generic brand competition, first-line antiretroviral drugs' prices dropped by more than 99%, from $10,000/year per patient in 2000 to less than $70 in 2014[11].

India

Many Indian families live below the poverty line due to healthcare expenses. From 1972 to 2005, due to a lack of patent laws for drugs in India, Indian drug companies were able to use alternative, legal processes to manufacture generic versions of drugs. These generic drug companies were able to produce low-priced drugs that were considered among the lowest in the world. This allowed India to provide free antiretroviral treatment to 340,000 HIV infected individuals in the country. Majority of adult antiretroviral drugs purchased for donor-funded programs in developing countries were supplied by Indian generic drug companies. In compliance to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), India reintroduced patent laws for drugs in 2015[10].

Legislation

Trips Agreement

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), is a multilateral agreement between all member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO), effective January 1995[15]. This agreement introduced global standards for enforcing and protecting nearly all forms of intellectual property rights (IPR), including those for patents and data protection. Under the TRIPS Agreement, WTO member nations, with a few exceptions, are required to adjust their laws to the minimum standards of IPR protection. Member nations are also obligated to follow specific enforcement guidelines, remedies, and dispute resolution procedures. Before TRIPS, other international conventions and laws did not specify minimum standards for intellectual property laws in the international trading system. The TRIPS Agreement is argued to have the greatest effect on the pharmaceutical industry and access to medicines[16]. It is argued that the TRIPS agreement negatively impacted generic drug industries in countries such as India. However, others argue that the agreement is open to interpretation. A clause in the TRIPS agreement allows compulsory licensing, which permits the manufacture of generic brands of patented drugs, at prices set in a competitive market in cases of national emergencies[17].

HIV/AIDS Crisis

For example, many believe that the HIV/AIDs crisis in Africa and South East Asia and the inadequate access to essential AIDs medications constitute a national emergency. Therefore, the TRIPS Agreement can be interpreted to allow the manufacture of generic brands of patented HIV/AIDs drugs[17].

Doha Declaration

Further legislation such as Doha Declaration of 2001 worked to rectify the negative impact of the TRIPS Agreement[18]. The Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, effective November 2001, was adopted by WTO Ministerial Conference of 2001. Many argued that the TRIPS Agreement hindered developing countries from implementing measures to improve access to affordable medicines, especially for diseases of public health concern, such as HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. The Doha Declaration responds to concerns of developing countries that patent protection rules and other IPRs were hindering access to affordable medicines for populations in those countries[19]. The Doha Declaration emphasizes the flexibility of the TRIPS Agreement and highlights the right of respective government to interpret the TRIPS Agreement in terms of public health. It refers to specific parts of TRIPS, such as the use of compulsory licensing for pharmaceutical drugs only in the case of a national emergency and circumstances of extreme urgency and the right to determine what constitutes this --such as to address public health issues[19]. The declaration also allows for countries without manufacturing capabilities to turn to a third country, such as Canada for the export of generic brands of patented medicines[18].

Global Challenges to Medication Access

HIV/AIDS Medication

Africa

There is estimated to be more than 4 million HIV infected individuals in South Africa.Out of this, only 10,000 individuals are able to afford access to vital essential AIDS medications at their current prices. In Malawi, out of one million infected individuals, only 30 have access to life-sustaining essential AIDS medications[17]. In Uganda, out of the estimated 820,000 infected individuals, only about 1.2% can afford essential AIDS medications[20].

Latin America

There is estimated to be 1.8 million individuals HIV infected individuals in the Latin American region. Brazil is argued to be one of the most affected by the AIDS epidemic. There is also a high prevalence of HIV in smaller countries such as Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize[21]. However, Brazil is argued not to have restrictive patent laws. In the mid 1990s, Brazil began manufacturing generic brands of vital AIDS medication. Due to this, Brazil's AIDS mortality rate declined by almost 50%[17].

Vaccines

The majority of deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases occur in low and middle income countries. In low-income countries, more than 90% of deaths are from pneumococcal disease, 95% from Hib, and 80% from hepatitis B. Although widely used by high-income countries, in 2006, Hib vaccine usage in Africa was about 24% In the Americas, Hepatitis B vaccine usage was at 90%. In Southeast Asia, where there is hepatitis B epidemic, the Hib vaccine coverage was only 28%. The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is considered the most expensive vaccine in history. However, the majority of those that suffer from cervical cancer are in developing countries[22].

Campaigns

A number of countries and organizations have efforts to improve access to medicines in specific areas of the world.

The Canada's Access to Medicines Regime allows developing countries to bring in medicines at lower cost.[23] It specifically allows companies in Canada who may not own the right to make a medication to do so for export to certain countries in the developing world.[24]

Médecins Sans Frontières has had such a campaign since 1999 known as the Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines.[25]

See also

References

- ^ "WHO Access to medicines". www.who.int. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ^ a b "Access to essential medicines as part of the right to health". World Health Organization. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Final Report High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines". Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Moon, Suerie (9 February 2017). "Powerful Ideas for Global Access to Medicines". New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (6): 505–507. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1613861.

- ^ "Intellectual Property and Access to Medicine for the Poor". Virtual Mentor. 8 (12). Leevy, Tara: 834–838. 2006-12-01. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.hlaw1-0612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Diependaele, Lisa; Cockbain, Julian; Sterckx, Sigrid (April 2017). "Raising the Barriers to Access to Medicines in the Developing World – The Relentless Push for Data Exclusivity". Developing World Bioethics. 17(1): 11–21.

- ^ M.D., Robert Pearl,. "Why Patent Protection In The Drug Industry Is Out Of Control". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Stevens, Hilde; Huys, Isabelle. "Innovative Approaches to Increase Access to Medicines in Developing Countries". Frontiers in Medicine. 4. doi:10.3389/fmed.2017.00218.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Schüklenk, Udo; Ashcroft, Richard E. (April 2002). "Affordable Access to Essential Medication in Developing Countries: ConflictsBetween Ethical and Economic Imperatives". Journal of Medicine & Philosophy. 27 (2): 179–95.

- ^ a b Grover, Anand; Citro, Brian. "India: access to affordable drugs and the right to health". The Lancet. 377 (9770): 976–977. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62042-9.

- ^ a b c Crager, Sara Eve. "Improving Global Access to New Vaccines: Intellectual Property, Technology Transfer, and Regulatory Pathways". American Journal of Public Health. 104 (11): e85–e91. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302236.

- ^ Norviel, Vern; Hoffmeister, David M. (September 30, 2015). "A Look At The Legality Behind Daraprim's Price Spike -". www.law360.com. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Muoio, Dave (September 17, 2015). "Daraprim price jump raises concerns among ID groups, providers". www.healio.com. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Schlanger, Zoë (2015-09-21). "Martin Shkreli on Raising Price of AIDS Drug 5,000 Percent: 'I Think Profits Are a Great Thing'". Newsweek. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "WTO | intellectual property - overview of TRIPS Agreement". www.wto.org. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ^ "WTO AND THE TRIPS AGREEMENT". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ^ a b c d Schüklenk, Udo; Ashcroft, Richard E. (April 2002). "Affordable Access to Essential Medication in Developing Countries: ConflictsBetween Ethical and Economic Imperatives". Journal of Medicine & Philosophy. 27 (2): 179–95.

- ^ a b Cohen-Kohler, J C (2007-11-01). "The Morally Uncomfortable Global Drug Gap". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 82 (5): 610–614. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100359. ISSN 1532-6535.

- ^ a b "THE DOHA DECLARATION ON THE TRIPS AGREEMENT AND PUBLIC HEALTH". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ^ AFP Report (March 23, 2001). "Price cuts have little impact on access to AIDS drugs in Uganda". Retrieved 2018-02-28.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Chequer, P., Sudo, E.C., & Vitfria, M.A.A. (2000). The impact of anti-retroviral therapy in Brazil. Paper presented at International AIDS Conference in Durban, paper no. MoPpE1066.

- ^ Crager, Sara Eve. "Improving Global Access to New Vaccines: Intellectual Property, Technology Transfer, and Regulatory Pathways". American Journal of Public Health. 104 (11): e85–e91. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302236.

- ^ Directorate, Government of Canada, Health Canada, Health Products and Food Branch, Therapeutic Products. "Canada's Access to Medicines Regime". www.camr-rcam.gc.ca. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Directorate, Government of Canada, Health Canada, Health Products and Food Branch, Therapeutic Products. "Introduction - Canada's Access to Medicines Regime". www.camr-rcam.gc.ca. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "About Us". Retrieved 10 February 2017.