Torksey

| Torksey | |

|---|---|

Torksey Lock slipway | |

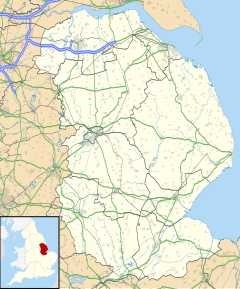

Location within Lincolnshire | |

| Population | 875 (2011 census) |

| OS grid reference | SK837786 |

| • London | 130 mi (210 km) S |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LINCOLN |

| Postcode district | LN1 |

| Police | Lincolnshire |

| Fire | Lincolnshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Torksey is a small village in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 875.[1] It is situated on the A156 road, 7 miles (11 km) south of Gainsborough and 9 miles (14 km) north-west of the city of Lincoln, and on the eastern bank of the tidal River Trent, which here forms the boundary with Nottinghamshire.

It is notable historically as the site of a Roman canal, a major Viking camp, the late medieval Torksey Castle and a Victorian railway bridge, Torksey Viaduct.

History

Foss Dyke, a Roman canal constructed in or about the 2nd Century, joins the River Trent by way of a series of lock-gates about half a mile (800 m) south of the village.

During the 9th Century, Torksey was part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Lindsey. In the late 860s, a Viking invasion force known to the English as the "Great Heathen Army" conquered eastern England. In 871–2, the Vikings established a winter camp in London, but returned to Northumbria soon afterwards, following a rebellion against their rule. During 872–3, the Great Heathen Army established its winter quarters at Torksey.[2]

The now Grade I listed 16th-century Torksey Castle was destroyed in August 1645 during the English Civil War; its remains are on the river side of the dike which separates it from dry land.

The Grade II* listed railway viaduct over the Trent remains but it is no longer in use.

Torksey Viaduct has two 130 feet (40 m) spans across the River Trent.[3] It was built between 1847 and 1849 to carry the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (Clarborough Junction-Sykes Junction branch). It is of unusual design and is regarded as the first box girder bridge.[4] It was designed by John Fowler, who had been influenced by Fairbairn and Stephenson's tubular bridges at Conwy and the Menai Straits. The tubular girder bridge was not initially accepted by the Board of Trade's inspector Lintorn Simmons;[5] this decision (and also the basic premise that a bridge designed by a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers which had passed all practical tests could be rejected by a railway inspector because he was uncomfortable with its novel design) was criticised by the ICE:[6] "The subject has been discussed in the Institution of Civil Engineers, and every eminent engineer was of the opinion that the Government inspector was clearly wrong". Threatened with a call for a parliamentary enquiry should approval continue to be withheld, the Railway Inspectorate reconsidered and approved the bridge un-modified.[7] Subsequently, and consequently, the Board of Trade took the view that (as it explained in defending itself from criticism that the defects in the Tay Bridge should have been seen and acted upon by the Railway Inspectorate): "The duty of an inspecting officer, so far as regards design, is to see that the construction is not such as to transgress those rules and precautions which practice and experience have proved to be necessary for safety. If he were to go beyond this, or if he were to make himself responsible for every novel design, and if he were to attempt to introduce new rules and practices not accepted by the profession, he would be removing from the civil engineer, and taking upon himself a responsibility not committed to him by Parliament."[8] Torksey bridge was strengthened in 1897 by adding a more conventional central truss above the deck rather than by strengthening the box.[6]

Both the castle and viaduct are on the Buildings at Risk Register.[citation needed]

The environmental charity Sustrans has carried out work on the viaduct in preparation for opening it as a walk/cycle-way[9] They obtained planning permission in 2015 for the paths, which Sustrans aimed to link as a walking and cycling route to connect the quiet roads east of Torksey with those west of Cottam, a village about 1.2 miles (2 km) to the west.[10] In April 2016, the viaduct was opened to both cyclists and walkers.[11]

See also

References

- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Haldenby, D. and Richards, J.D. (2016) The Viking Great Army and its Legacy: plotting settlement shift using metal-detected finds, Internet Archaeology 42. Retrieved 13 December 2016

- ^ Tatraskoda. "John Fowler's Viaduct at Torksey". Flickr.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ "Torksey Bridge".

- ^ Thomas Mackay (18 April 2013). The Life of Sir John Fowler, Engineer. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–104. ISBN 978-1-108-05767-7.: pages cited give the affair and Fowler's subsequent views

- ^ a b "Torksey Viaduct". www.forgottenrelics.co.uk. Forgotten Relics.

- ^ "Torksey Bridge". Sheffield Independent. 13 April 1850. p. 5.

- ^ "Report by the Board of Trade". Dundee Courier. 23 July 1880. p. 3.

- ^ Sustrans Torksey Bridge page

- ^ "Scunthorpe Telegraph 11 March 2015 'Landmark railway viaduct to become public walkway'". Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Historic Torksey viaduct opens to link communities". Retrieved 6 June 2019.