Apollo/Skylab spacesuit

The names for both the Apollo and Skylab spacesuits were Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU).[2] The Apollo EMUs consisted of a Pressure Suit Assembly (PSA) aka "suit" and a Portable Life Support System (PLSS) that was more commonly called the “backpack”.[3] The A7L was the PSA model used on the Apollo 7 through 14 missions.[4] The subsequent Apollo 15-17 lunar missions,[5] Skylab,[6] and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project used A7LB pressure suits.[7] Additionally, these pressure suits varied by program usage. For the Skylab EMU, NASA elected to use an umbilical life support system named the Astronaut Life Support Assembly.

Basic design

The base Apollo EMU design took over three years to produce. At the beginning of the Apollo program, the Apollo spacesuit had not yet received its final EMU name. Between 1962 and 1964, the spacesuit was called the Space Suit Assembly (SSA). The Apollo SSA consisted of a Pressure Garment Assembly (PGA) and a backpack Portable Life Support System (PLSS).

NASA held a competition for the Apollo SSA contract in March 1962. Each competition proposal had to demonstrate all the abilities needed to develop and produce the entire SSA. Many contractor-teams submitted proposals. Two gained NASA interest. The Hamilton Standard Division of United Aircraft Corporation proposal offered Hamilton providing the SSA program management and PLSS with David Clark Company as the PGA provider. The International Latex Corporation (ILC)proposal planned International Latex as the SSA program manager and PGA manufacturer, Republic Aviation providing additional suit experience and Westinghouse providing the PLSS.

After evaluation of the proposals, NASA preferred the Hamilton PLSS concept and program experience but the ILC PGA design. NASA elected to split the Hamilton and ILC teams, issuing the contract to Hamilton with the stipulation that ILC provide the PGA.

By March 1964, Hamilton and NASA had found three successive ILC Apollo PGA designs to not meet requirements. In comparative testing, only the David Clark Gemini suit was acceptable for Apollo Command Module use. While the Hamilton PLSS met all requirements, crewed testing proved the life support requirements were inadequate forcing the Apollo SSA program to start over.

In October 1964, NASA elected to split the spacesuit program into three parts. David Clark would provide the suits for the “Block I” early missions without extra-vehicular activity (EVA). The Hamilton/ILC program would continue as “Block II” to support the early EVA missions. The pressure suit design for Block II was to be selected in a June 1965 re-competition. To assure Block II backpack success, AiResearch was funded for a parallel backpack effort. The later, longer-duration Apollo missions would be Block III and have more advanced pressure suits and a longer duration backpack to be provided by suppliers selected in future competitions. To reflect this new start in the program, the PGA was renamed the Pressure Suit Assembly (PSA)across the programs and the Block II and III SSAs were renamed Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU).

Hamilton and International Latex were never able to form an effective working relationship. In March 1965, Hamilton switched to B. F. Goodrich as suit supplier.[8] International Latex, in July 1965, won the Block II suit competition with its A5L design. This forced NASA to assume management of the Block II EMU program directly.[9] Before the end of 1965, Hamilton Standard completed certification of its new backpack.[10] NASA subsequently terminated the Block II AiResearch backpack, thus completing the selection of the suit/backpack designs and suppliers to support man's first walking on the Moon. However, this was not to be without improvements. The Apollo 11 EMU featured an A7L suit with a -6 (dash six) backpack reflecting seven suit and six backpack design iterations.[4] The A7L was a rear entry suit made in two versions. The Extra-vehicular (EV), which would be used on the Moon and the Command Module Pilot (CMP) that was a simpler garment.[2]

The A7L pressure suits reached space flight in October 1968 aboard Apollo 7.[11] These were used as launch and reentry emergency suits. Also in 1968, NASA recognized that with modifications, the Block II EMU could additionally support the later EVA missions that involved a Lunar Rover Vehicle (LRV). This resulted in the termination of Apollo Block III in favor of an Apollo 15 through 17 EMU using an A7LB suit and a “-7” long duration backpack.[2]

The complete Apollo EMU made its space debut with Apollo 9 launched into space on March 3, 1969.[12] On the fourth day of the mission, Lunar Module Pilot Russell Schweickart and Commander James McDivitt went into the Lunar Module. The astronauts then depressurized both the Command and Lunar Modules. Schweickart emerged from the Lunar Module to test the backpack and conduct experiments. David Scott partially emerged from the Command Module's hatch supported by an umbilical system connected to the Command Module to observe. The EVA lasted only 46 minutes but allowed a verification of both EVA configurations of the EMU. This was the only Apollo spacewalk prior to the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission.

Apollo 11 made the A7L the most iconic suit of the program. It proved to be the primary pressure suit worn by NASA astronauts for Project Apollo. Starting in 1969, the A7L suits were designed and produced by ILC Dover (a division of Playtex at the time). The A7L is an evolution of ILC's initial A5L, which won a 1965 pressure suit competition, and A6L, which introduced the integrated thermal and micrometeroid cover layer. After the deadly Apollo 1 fire, the suit was upgraded to be fire-resistant and designated A7L.[13][14]

On July 20, 1969, the Apollo 11 EMUs were prominent in television coverage of the first lunar landing. Also in 1969, International Latex elected to spin-off its pressure suit business to form ILC Dover.

The basic design of the A7L suit was a one piece, five-layer "torso-limb" suit with convoluted joints made of synthetic and natural rubber at the shoulders, elbows, wrist, hips, ankle, and knee joints. A shoulder "cable/conduit" assembly allowed the suit's shoulder to move forward, backwards, up, or down with user movements. Quick disconnects at the neck and forearms allowed for the connection of the pressure gloves and the famous Apollo "fishbowl helmet" (adopted by NASA as it allowed an unrestricted view, as well as eliminating the need for a visor seal required in the Mercury and Gemini and Apollo Block I spacesuit helmets). A cover layer, which was designed to be fireproof after the deadly Apollo 1 fire, was attached to the pressure garment assembly and was removable for repairs and inspection. All A7L suits featured a vertical zipper from the helmet disconnect (neck ring), down the back, and around the crotch.

Specifications, Apollo 7 - 14 EMU

- Name: Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU)

- Manufacturer: ILC Dover (Pressure Suit Assembly) and Hamilton Standard (Portable Life Support System)[2]

- Missions: Apollo 7-14[2]

- Function: Intra-vehicular activity (IVA), orbital Extra-vehicular activity (EVA), and terrestrial EVA[2]

- Operating Pressure: 3.7 psi (25.5 kPa)[2]

- IVA Suit Mass: 62 lb (28.1 kg)[2]

- EVA Suit Mass: 76 lb (34.5 kg)[2]

- Total EVA Suit Mass: 200 lb (91 kg)[2]

- Primary Life Support: 6 hours[2]

- Backup Life Support: 30 minutes[2]

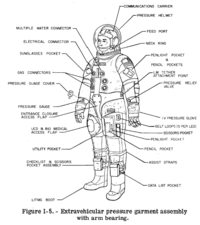

Extravehicular Pressure Suit Assembly

Torso Limb Suit Assembly

Between Apollos 7 and 14, the two lunar module astronauts, the Commander (CDR) and Lunar Module pilot (LMP), had Torso Limb Suit Assemblies (TSLA) with six life support connections placed in two parallel columns on the chest. The 4 lower connectors passed oxygen, an electrical headset/biomed connector was on the upper right, and a bidirectional cooling water connector was on the upper left.

Integrated Thermal Micrometeoroid Garment

Covering the Torso Limb Suit Assembly was an Integrated Thermal Micrometeoroid Garment (ITMG). This garment protected the suit from abrasion and protected the astronaut from thermal solar radiation and micrometeoroids which could puncture the suit. The garment was made from thirteen layers of material which were (from inside to outside): rubber coated nylon, 5 layers of aluminized Mylar, 4 layers of nonwoven Dacron, 2 layers of aluminized Kapton film/Beta marquisette laminate, and Teflon coated Beta filament cloth.

Additionally, the ITMG also used a patch of 'Chromel-R' woven nickel-chrome (the familiar silver-colored patch seen especially on the suits worn by the Apollo 11 crew) for abrasion protection from the Portable Life Support System (PLSS) backpack. Chromel-R was also used on the uppers of the lunar boots and on the EVA gloves. Finally, patches of Teflon were used for additional abrasion protection on the knees, waist and shoulders of the ITMG.

Starting with Apollo 13, a red band of Beta cloth was added to the commander's ITMG on each arm and leg, as well as a red stripe on the newly added EVA central visor assembly. The stripes, initially known as "Public Affairs stripes" but quickly renamed "commander's stripes", made it easy to distinguish the two astronauts on the lunar surface and were added by Brian Duff, head of Public Affairs at the Manned Spacecraft Center, to resolve the problem for the media as well as NASA of identifying astronauts in photographs.[15]

Liquid Cooling Garment

Lunar crews also wore a three-layer Liquid Cooling and Ventilation Garment (LCG) or "union suit" with plastic tubing which circulated water to cool the astronaut down, minimizing sweating and fogging of the suit helmet. Water was supplied to the LCG from the PLSS backpack, where the circulating water was cooled to a constant comfortable temperature by a sublimator.

Portable Life Support System

At the beginning of the Apollo spacesuit competition, no one knew how the life support would attach to the suit, how the controls needed to be arranged, or what amount of life support was needed. What was known was that in ten months, the Portable Life Support System, aka “backpack”, needed to be completed to support complete suit-system testing before the end of the twelfth month. Before the spacesuit contract was awarded, the requirement for normal life support per hour almost doubled. At this point, a maximum hourly metabolic energy expenditure requirement was added, which was over three times the original requirement.[16]

In late 1962, testing of an early training suit raised concerns about life support requirements. The concerns were dismissed because the forthcoming Apollo new-designs were expected to have lower effort mobility and improved ventilation systems. However, Hamilton took this as a strong indication that Apollo spacesuit life support requirements might significantly increase and initiated internally funded research and development in “backpack” technologies.

In the tenth month, the first backpack was completed. Manned testing found the backpack to meet requirements. This would have been a great success but for the crewed testing confirming that the 1963 life support requirements were not sufficient to meet lunar mission needs. Early in 1964, the final Apollo spacesuit specifications were established that increased normal operations by 29% and increased maximum use support 25%. Again, the volume and weight constraints did not change. These final increases required operational efficiencies that spawned the invention of the porous plate sublimator[17] and the Apollo liquid cooling garment.[18]

The porous plate sublimator had a metal plate with microscopic pores sized just right so that if the water flowing under the plate warmed to more than a user-comfortable level, frozen water in the plate would thaw, flow through the plate, and boil to the vacuum of space, taking away heat in the process. Once the water under the plate cooled to a user-comfortable temperature, the water in the plate would re-freeze, sealing the plate and stopping the cooling process. Thus, heat rejection with automatic temperature control was accomplished with no sensors or moving parts to malfunction.

The Apollo liquid cooling garment was an open mesh garment with attached tubes to allow cooling water to circulate around the body to remove excess body heat when needed. The garment held the tubes against body for highly efficient heat removal. The open mesh allowed air circulation over the body to remove humidity and additionally remove body heat. In 1966, NASA bought the rights to the liquid cooling garment to allow all organizations access to this technology.

Before the first Apollo spacewalk, the backpack gained a front-mounted display and control unit named the remote control unit. This was revised for Apollo 11 to additionally provide camera attachment to provide high quality lunar pictures.

Intravehicular (CMP) Pressure Suit Assembly

Torso Limb Suit Assembly

The Command Module pilot (CMP) had a TSLA similar to the commander and lunar module pilot, but with unnecessary hardware deleted since the CMP would not be performing any extravehicular activities. For example, the CMP's TSLA had only one set of gas connectors instead of two, and had no water cooling connector. Also deleted was the pressure relief valve in the sleeve of the suit and the tether mounting attachments which were used in the lunar module. The TSLA for the CMP also deleted an arm bearing that allowed the arm to rotate above the elbow.

Intravehicular Cover Layer

Command module pilots only wore a three-layer Intravehicular Cover Layer (IVCL) of nomex and beta cloth for fire and abrasion protection.

Constant Wear Garment

The CMP wore a simpler cotton fabric union suit called the Constant Wear Garment (CWG) underneath the TSLA instead of the water cooled Liquid Cooling Garment. His cooling came directly from the flow of oxygen into his suit via an umbilical from the spacecraft environmental control system. When not performing lunar EVA's, the LMP and CDR also wore a CWG instead of the LCG.

Apollo 15-17, Skylab and ASTP Spacesuits

Apollo 15-17 EMU

For the last three Apollo lunar flights Apollos 15, 16, and 17, the spacesuits were extensively revised. The pressure suits were called A7LB, which came in two versions. The Extra-vehicular (EV) version was a new mid-entry suit that allowed greater mobility and easier operations with the lunar rover. The A7LB EV suits were designed for longer duration J-series missions, in which three EVAs would be conducted and the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) would be used for the first time. Originally developed by ILC-Dover as the "A9L," but given the designation "A7LB" by NASA,[19] the new suit incorporated two new joints at the neck and waist. The waist joint was added to allow the astronaut to sit on the LRV and the neck joint was to provide additional visibility while driving the LRV. Because of the waist joint, the six life-support connectors were rearranged from the parallel pattern to a set of two "triangles," and the up-and-down back zipper was revised and relocated.[14] The "zipper" is actually a misnomer in that the A7L entry was through two zippers sewn over each other. The inner zipper had rubber teeth and provided sealing. The outer (externally visible) zipper was a conventional metal toothed slider for mechanical restraint. The A7LB had two pairs of such zipper sets that intersected on the right side of the suit above the waist joint. Opening the suit required undoing a clasp that held the zipper sets together.[citation needed]

In addition, the EVA backpacks were modified to carry more oxygen, lithium hydroxide (LiOH), more power, and cooling water for the longer EVAs.[14] While NASA wished these revisions to be accomplished without a volume increase, that was not possible. NASA allowed a minor protrusion on one side for an auxiliary water tank resulting in the last configuration of backpack. To maximize the return of lunar samples, the main module of both the Apollo 11-14 and 15-17 backpacks were left on the Moon.

To facilitate these longer EVAs, small energy bars were carried in special pouches beneath the interior of the suit helmet ring, and the astronauts wore collar-like drinking water bags beneath the outer suit.

Because the Vietnam War had taken toll on the federal budget, NASA's budget was in decline. The Command Module Pilot did not get a new mid-entry suit. NASA elected to modify existing A7L EV units by simply removing the liquid cooling features to create a “new” A7LB CMP suit. Once the existing inventory was consumed, a few new A7LB CMP suits were made to support Apollo 17.

Because the J-series CSMs incorporated the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) Bay, which used special film cameras similar to those used on Air Force spy satellites, and required a "deep space" EVA for retrieval, the CMP for each of the three J-series missions wore a five-connector A7LB-based H-series A7L suits, with the liquid cooling connections eliminated as the CMP would be attached to a life-support umbilical (like that used on Gemini EVAs) and only an "oxygen purge system" (OPS) would be used for emergency backup in the case of the failure of the umbilical. The CMP wore the commander's red-striped EVA visor assembly, while the LMP, who performed a "stand-up EVA" (to prevent the umbilical from getting "fouled up" and to store the film into the CSM) in the spacecraft hatch and connected to his normal life-support connections, wore the plain white EVA visor assembly.

Specifications

- Name: Apollo 15-17 EMU

- Manufacturer: ILC Dover (Pressure Suit Assembly) Hamilton Standard (Primary Life Support System)[2]

- Missions: Apollo 15-17[2]

- Function: Intra-vehicular activity (IVA), orbital Extra-vehicular activity and terrestrial Extra-vehicular activity (EVA)

- Operating Pressure: 3.7 psi (25.5 kPa)[2]

- IVA Suit Mass: 64.6 lb (29.3 kg)[2]

- EVA Suit Mass: 78 lb (35.4 kg)[2]

- Total EVA Suit Mass: 212 lb (96.2 kg)[2]

- Primary Life Support: 7 hours (420 minutes)[2]

- Backup Life Support: 30 minutes[2]

Skylab EMU

The American space station was named Skylab and it had three crewed flights. To minimize program costs, NASA elected to fund ILC Dover for modifications to the mid-entry Apollo A7LB EV PSA design to reduce costs and use an umbilical system named the Astronaut Life Support Assembly (ALSA) to allow extra-vehicular activities. AiResearch won the competition for the ALSA. The result was the Skylab EMU. During launch, the space station was damaged. The Skylab EMUs enabled emergency repair and outfitting tasks that permitted the program to conduct its long duration crewed missions and experiments. Skylab returned to all the crew members having the same configuration suits.

With the exception of the Orbital Workshop (OWS) repairs carried out by Skylab 2 and Skylab 3, all of the Skylab EVAs were conducted in connection to the routine maintenance carried out on the Apollo Telescope Mount, which housed the station's solar telescopes. Because of the short duration of those EVAs, and as a need to protect the delicate instruments, the Apollo lunar EVA backpack was replaced with an umbilical assembly designed to incorporate both breathing air (Skylab's atmosphere was 74% oxygen and 26% nitrogen at 5 psi) and liquid water for cooling. The assembly was worn on the astronaut's waist and served as the interface between the umbilical and the suit. An emergency oxygen pack was strapped to the wearer's right thigh and was able to supply a 30-minute emergency supply of pure oxygen in the case of umbilical failure. Another unique feature of the Skylab EMU was its simplified EVA visor assembly that did not include an insulated thermal cover over the outer visor shell.

There were three crewed Skylab flights. All three missions included “space walks.”

Specifications

- Name: Skylab EMU

- Manufacturer: ILC Dover (Pressure Suit Assembly) and AiResearch (bought by AlliedSignal Corporation)(Astronaut Life Support Assembly) [2]

- Missions: Skylab 2-4[2]

- Function: Intra-vehicular activity (IVA) and orbital Extra-vehicular activity (EVA)[2]

- Operating Pressure: 3.7 psi (25.5 kPa)[2]

- IVA Suit Mass: 64.6 lb (29.3 kg)[2]

- EVA Suit Mass: 72 lb (32.7 kg)[2]

- Total EVA Suit Mass: 143 lb (64.9 kg)[2]

- Primary Life Support: Vehicle Provided via ALSA[2]

- Backup Life Support: 30 minutes[2]

ASTP Spacesuit

For the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, NASA decided to use the A7LB CMP pressure suit assembly worn on the J-missions with a few changes to save cost and weight since an EVA was not planned during the mission. The changes included a simplified cover layer which was cheaper, lighter and more durable as well as the removal of the pressure relief valve and unused gas connectors. No EVA visor assemblies or EVA gloves were carried on the mission.[20]

The ASTP A7LB suit was the only Apollo suit to use the NASA "worm" logo, which was introduced in 1975 and used extensively by NASA until 1992.

Specifications

- Name: Apollo A7LB Pressure Suit Assembly

- Manufacturer: ILC Dover[2]

- Missions: ASTP[2]

- Function: Intra-vehicular activity (IVA)[2]

- Operating Pressure: 3.7 psi (25.5 kPa)[2]

- IVA Suit Mass: 64.6 lb (29.3 kg)[2]

- Primary Life Support: Vehicle Provided

References

- ^ "Science Friday Archives: How to Dress for Space Travel". NPR. March 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Kenneth S. Thomas; Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. pp. 428–435. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas; Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. pp. 428–433. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ a b Kenneth S. Thomas; Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. pp. 428–429. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas; Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. pp. 430–431. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas; Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. pp. 432–433. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas; Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. pp. 434–435. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 99–103. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 88–114. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 80–87. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 155–162. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 162–169. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ "SP-4011:Skylab A Chronology". NASA. 1977. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ a b c Charles C. Lutz; Harley L. Stutesman; Maurice A. Carson; James W. McBarron II (1975). "Development of the Extravehicular Mobility Unit". NASA. Archived from the original on 1 August 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ "Commander's Stripes". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. NASA.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 34–39. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas (2017). The Journey To Moonwalking. Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK: Curtis Press. pp. 59–65, 81–83. ISBN 9-780993-400223.

- ^ Harold J. McMann; Thomas, Kenneth P. US Spacesuits (Springer Praxis Books / Space Exploration). Praxis. pp. 171–172. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ "Apollo ASTP Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. 10 June 1975. p. 53. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

External links

- NASA JSC Oral History Project Walking to Olympus: An EVA Chronology PDF document.

- Apollo Operations Handbook Extravehicular Mobility Unit: Volume I: System Description: Apollo 14

- Apollo Extravehicular mobility unit. Volume 1: System description - 1971 (PDF document)

- Apollo Extravehicular mobility unit. Volume 2: Operational procedures - 1971 (PDF document)

- Skylab Extravehicular Activity Development Report - 1974 (PDF document)

- A history of NASA space suits

- APOLLO EXPERIENCE REPORT DEVELOPMENT OF THE EXTRAVEHICULAR MOBILITY (PDF Document)

- A visual history of project Apollo including many space suit photographs

- ILC Spacesuits and Related Products