Cocinero

| Cocinero | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Carangiformes |

| Family: | Carangidae |

| Genus: | Caranx |

| Species: | C. vinctus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Caranx vinctus D. S. Jordan & C. H. Gilbert, 1882

| |

| |

| Approximate range of the cocinero | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The cocinero (Caranx vinctus), also known as the barred jack and striped jack, is a species of small marine fish classified in the jack family, Carangidae. The cocinero is distributed through the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean, ranging along the west American coastline from Baja California in the north to Peru in the south. It is a pelagic species, inhabiting the upper water column in both coastal and offshore oceanic waters, occasionally making its way into estuaries. The species may be identified by its colouration, having 8 or 9 incomplete dark vertical stripes on its sides, with scute and gill raker counts also diagnostic. It is small compared to most other species of Caranx, reaching a length of 37 cm in total. The cocinero is a predatory fish, taking small fishes, crustaceans, and various benthic invertebrates in shallower waters. Little is known of the species' reproductive habits. The cocinero is of moderate importance to fisheries along the west coast of South America, and the species has been used in aquaculture trials. It is taken by various netting methods and by spear, and is sold fresh, dried, and salted at market.

Taxonomy and naming

The cocinero is classified within the genus Caranx, one of a number of groups known as the jacks or trevallies. Caranx itself is part of the larger jack and horse mackerel family Carangidae, which in turn is part of the order Carangiformes.[3]

The species was first scientifically described by the American ichthyologists David Starr Jordan and Charles Henry Gilbert in 1882 based on a specimen taken off Sinaloa, Mexico, which became the holotype.[4] They named the new species Caranx vinctus, with the specific epithet of Latin origin meaning "bound" or "laced", presumably a description of the species vertical striping. The species has been variably placed in either Caranx or Carangoides ever since, with a recent molecular phylogeny study indicating the species is most closely related to other species of Caranx.[5] The species was later transferred to the now defunct genus Xurel by Jordan and Evermann, who created the genus. Xurel was later synonymised with Carangoides, thus the species was placed in Carangoides under this classification.[6] A species by the name was of Caranx fasciatus was created by Georges Cuvier in 1833, which was based on a sketch of a specimen taken from "American waters". The sketch may be of Caranx vinctus, but it is not anatomically detailed, and the species is rendered a nomen dubium.[7] The species common name, cocinero, is the Spanish word for cook or chef, with barred jack and striped jack also occasionally used.[2]

Description

The cocinero is a relatively small species in comparison with most species of Caranx, reaching a known length of 37 cm.[2] The species has a fairly similar body profile compared to the members of this genus, having a relatively deep, compressed-ovate form, although its body is slightly more elongated than the other species. The dorsal profile is slightly more convex than the ventral profile, particularly anteriorly, with the snout slightly pointed.[8] The dorsal fin is in two distinct parts, the first consisting of eight spines, while the second has one spine and 22 or 24 soft rays. The anal fin consists of two detached spines anteriorly followed by one spine and 18 to 21 soft rays, with the lobes of both fins only slightly extended.[9] The lateral line has a strong anterior curve, with the straight section containing none to four scales and 46 to 53 strong scutes.[8] The breast area is fully scaled. The eyes have a slightly developed posterior adipose eyelid, while the upper jaw contains an outer row of strong canines and an inner band of villiform teeth, while the lower jaw has only a single row of canine teeth. There are 39 to 44 gill rakers in total and 25 vertebrae in the species.[8]

The cocinero is a dusky-blue color dorsally, fading to a silvery-white ventral surface, often with golden-green reflections when fresh. There are 8 or 9 incomplete dark vertical bars on the side, and an obvious dark spot on the upper operculum.[9] Juveniles are much paler, with the dark vertical bars more pronounced, and having dusky to dark fins.[10] The pectoral, pelvic, and spinous dorsal fins are hyaline to dusky, while the second dorsal fin is yellow distally. The caudal and anal fins are yellow to dusky yellow.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The cocinero is distributed through the tropical and subtropical waters of the eastern Pacific Ocean. The species ranges along the American coastline from Baja California in the north to Peru in the south,[2] possibly including the Gulf of California.[8]

The cocinero is pelagic in nature, inhabiting the top 40 m of the water column in both offshore oceanic waters and inshore coastal waters.[8] The species has been observed in estuaries and tidal mangrove zones of inshore waters.[11] Like many Pacific species, the abundance of cocinero in fishery catches appears to be correlated with the effects of El Nino and La Nina weather events. During 'normal' years, the species becomes more abundant in the tropical (June–December) season, while during the El Nino and La Nina events, it changes to the January–May period.[12]

Biology and fishery

Little is known about the biology of the cocinero, with only the broad diet and short-term growth rates studied. The species is predatory, taking small fish and crustaceans, as well as various benthic invertebrates in shallower waters.[2] Cage studies in less than optimal estuarine water conditions found the cocinero has a daily growth rate between 0.37 and 0.55 g/day, with this noted as being much slower as some Indo-Pacific carangids. The authors of this study concluded this was partly due to the water being polluted with hydrocarbons, and less than optimal feed being given.[13]

The species is of moderate importance to the western Central and South American fisheries, being taken predominantly by various net methods.[8] Individual catch statistics are not kept for the species; instead. it is lumped with other species of Caranx. The species is sold fresh, salted, and dried.[8] Caged aquaculture studies have been conducted, although poor production was observed due to reasons explained above. The species was found to have a low mortality rate, and was seemingly unaffected by parasites or diseases during the trial.[13] The cocinero is also considered a gamefish, taken by line and spear.[14]

References

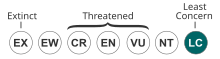

- ^ Smith-Vaniz, B.; Robertson, R.; Dominici-Arosemena, A.; Molina, H. (2010). "Caranx vinctus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T183293A8088434. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T183293A8088434.en.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Caranx vinctus". FishBase. August 2019 version.

- ^ J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 380–387. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- ^ California Academy of Sciences: Ichthyology (February 2009). "Caranx vinctus". Catalog of Fishes. CAS. Retrieved 2009-05-16.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Reed, David L.; Carpenter, Kent E.; deGravelle, Martin J. (2002). "Molecular systematics of the Jacks (Perciformes: Carangidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences using parsimony, likelihood, and Bayesian approaches". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 23 (3). USA: Elsevier Science: 513–524. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00036-2. PMID 12099802.

- ^ Rivero, H.Y. (1938). "List of the Fishes, Types of Poey, in the Museum of Comparative Zoology". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 82 (3): 169–227.

- ^ Berry, F.H. (1963). "Caranx fasciatus Cuvier, an Unidentifiable Name for a Carangid Fish". Copeia. 1963 (3): 583–584. doi:10.2307/1441495. JSTOR 1441495.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fischer, W.; Krupp F.; Schneider W.; Sommer C.; Carpenter K.E.; Niem V.H. (1995). Guía FAO para la identificación de especies para los fines de la pesca. Pacífico centro-oriental. Volumen II. Vertebrados - Parte 1. Rome: FAO. p. 953. ISBN 92-5-303409-2.

- ^ a b Allen, G.R.; D.R. Robertson (1994). Fishes of the tropical eastern Pacific. University of Hawaii Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-8248-1675-9.

- ^ Nichols, J.T. (1944). "On the Young of Caranx vinctus Jordan and Gilbert". Copeia. 1944 (2): 124. doi:10.2307/1438775. JSTOR 1438775.

- ^ Cartron, J.E.; G. Ceballos; R.S. Felger (2005). Biodiversity, ecosystems, and conservation in northern Mexico. Oxford University Press US. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-19-515672-0.

- ^ Godınez-Domıngueza, E.; J. Rojo-Vazquez; V. Galvan-Pin; B. Aguilar-Palomino (2000). "Changes in the Structure of a Coastal Fish Assemblage Exploited by a Small Scale Gillnet Fishery During an El Nino–La Nina Event". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 51 (6): 773–787. doi:10.1006/ecss.2000.0724.

- ^ a b Rubio, E.A.; J.H. Loaiza; R. Arroyo (2000). "Aspectos sobre el crecimiento en jaulas flotantes de Caranx caninus Y Caranx vinctus (Pisces:Carangidae) en agua estuarinas de la Bahia de Buenaventra" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- ^ Walford, L.A. (1937). Marine Game Fishes of the Pacific Coast from Alaska to the Equator. University of California Press. p. 205.