Bytom

Bytom

Bytōm / Bytōń (Silesian) | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Silesian Opera; Historic tram (in background Main Post Office); Dworcowa Street; Market square; Szombierki Heat Power Station; View of Władysław Sikorski Square; Church of St. Margaret | |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 50°20′54″N 18°54′56″E / 50.34833°N 18.91556°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Silesian |

| County | city county |

| Established | 12th century |

| City rights | 1254 |

| Government | |

| • City mayor | Mariusz Wołosz (KO) |

| Area | |

• City | 69.44 km2 (26.81 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 330 m (1,080 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 249 m (817 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2021) | |

• City | 161,139 |

| • Density | 2,321/km2 (6,010/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,710,397 |

| • Metro | 5,294,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 41-900–41-936 |

| Area code | +48 32 |

| Car plates | SY |

| Primary airport | Katowice Airport |

| Website | www |

Bytom (Polish pronunciation: [ˈbɨtɔm] ⓘ; Silesian: Bytōm, Bytōń, German: Beuthen O.S.) is a city in Upper Silesia, in southern Poland. Located in the Silesian Voivodeship, the city is 7 km northwest of Katowice, the regional capital.

It is one of the oldest cities in the Upper Silesia, and the former seat of the Piast dukes of the Duchy of Bytom. Until 1532, it was in the hands of the Piast dynasty, then it belonged to the Hohenzollern dynasty. After 1623 it was a state country in the hands of the Donnersmarck family. From 1742 to 1945 the town was within the borders of Prussia and Germany, and played an important role as an economic and administrative centre of the local industrial region. Until the outbreak of World War II, it was the main centre of national, social, cultural and publishing organisations fighting to preserve Polish identity in Upper Silesia. In the interbellum and during World War II, local Poles and Jews faced persecution by Germany.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 173,955 | — |

| 1960 | 182,578 | +5.0% |

| 1970 | 187,500 | +2.7% |

| 1978 | 230,844 | +23.1% |

| 1988 | 228,306 | −1.1% |

| 2002 | 193,546 | −15.2% |

| 2011 | 176,902 | −8.6% |

| 2021 | 153,274 | −13.4% |

| source[2][3][4] | ||

After the war, decades of the Polish People's Republic were characterized by a constant emphasis on the development of heavy industry, which deeply polluted and degraded Bytom. After 1989, the city experienced a socio-economic decline. The population has also been rapidly declining since 1999. However, it is an important place in the cultural, entertainment, and industrial map of the region.

Geology

The bedrock of the Upland of Miechowice consists primarily of sandstones and slates. The rocks are punctuated with abundant natural resources of coal and iron ore from the Carboniferous period. In the north part of the upland, in the Bytom basin lays the broad range of the triassic rocks, from sandstones to limestones, with rich ore, zinc and lead reserves. The upper layer is composed of clay, sand and gravel.

Coat of arms

One half of the coat of arms of Bytom depicts a miner mining coal, while the other half presents a yellow eagle on the blue field – the symbol of Upper Silesia.

History

Bytom is one of the oldest cities of Upper Silesia, originally recorded as Bitom in 1136, when it was part of the Medieval Kingdom of Poland. Archaeological discoveries have shown that there was a fortified settlement (a gród) here, probably founded by the Polish King Bolesław I the Brave in the early 11th century.[5]

After the fragmentation of Poland in 1138, Bytom became part of the Seniorate Province, as it was still considered part of historic Lesser Poland. In 1177 it became part of the Silesian province of Poland, and remained within historic Silesia since.[6] Bytom received city rights from Prince Władysław in 1254 with its first centrally located market square. The city of Bytom benefited economically from its location on a trade route linking Kraków with Silesia from east to west, and Hungary with Moravia and Greater Poland from north to south. The first Roman Catholic Church of the Virgin Mary was built in 1231. In 1259 Bytom was raided by the Mongols. The Duchy of Opole was split and in 1281 Bytom became a separate duchy, since 1289 under overlordship and administration of the Kingdom of Bohemia. It existed until 1498, when it was re-integrated with the Piast-ruled Duchy of Opole. Due to German settlers coming to the area, the city was being Germanized.

It came under the control of the Habsburg monarchy of Austria in 1526, which increased the influence of the German language. In 1683, Polish King John III Sobieski and his wife Queen Marie Casimire, visited the city, greeted by the townspeople and clergy, on the king's way to the Battle of Vienna.[7] The city became part of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1742 during the Silesian Wars and part of the German Empire in 1871. In the 19th and the first part of the 20th centuries, the city rapidly grew and industrialized.

Bytom was one of the main centers of Polish resistance against Germanization in Upper Silesia in the 19th century, up until the mid-20th century. Polish social, political and cultural organizations were formed and operated here. From 1848, the newspaper Dziennik Górnośląski was published here. Poles smuggled large amounts of gunpowder through the city to the Russian Partition of Poland during the January Uprising in 1863.[8] According to the Prussian census of 1905, the city of Beuthen had a population of 60,273, of which 59% spoke German, 38% spoke Polish and 3% were bilingual.[9] In 1895, the "Sokół" Polish Gymnastic Society was established, and, during the Silesian uprisings, in 1919–1920, Polish football clubs Poniatowski Szombierki and Polonia Bytom were founded, which later on, in post-World War II Poland both won the national championship. After World War I, in the Upper Silesian plebiscite of 1921, 74.7% of the votes in Beuthen city were for Germany, and 25.3% were for Poland, due to which it remained in Germany, as part of the Province of Upper Silesia.[10] In the interwar period, Bytom was one of two cities (alongside Kwidzyn) in Germany, in which a Polish gymnasium was allowed to operate. In 1923 a branch of the Union of Poles in Germany was established in Bytom. There was also a Polish preschool,[11] two scout troops and a Polish bank.[12] In a secret Sicherheitsdienst report from 1934, Bytom was named one of the main centers of the Polish movement in western Upper Silesia.[13] Polish activists were persecuted since 1937.[14] The Bytom Synagogue was burned down by Nazi German SS and SA troopers during the Kristallnacht on 9–10 November 1938. Before 1939, the town, along with Gleiwitz (now Gliwice), was at the southeastern tip of German Silesia.

World War II and post-war period

During the German invasion of Poland, which started World War II, the Germans carried out mass arrests of local Poles. On September 1, 1939, the day of the outbreak of the war, Adam Bożek, the chairman of the Upper Silesian district of the Union of Poles in Germany, was arrested in Bytom and then deported to the Dachau concentration camp.[15] The Germans carried out revisions in the Polish gymnasium and the local Polish community centre, 20 Polish activists were arrested on September 4, 1939, then released and arrested again a few days later to be deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp.[16] Also three Polish teachers, who had not yet fled, were arrested, while the assets of the Polish bank were confiscated.[17] The Einsatzgruppe I entered the city on September 6, 1939, to commit atrocities against Poles.[18] Many Poles were conscripted to the Wehrmacht and died on various war fronts, including 92 former students of the Polish gymnasium.[19] The Beuthen Jewish community was liquidated via the first ever Holocaust transport to be exterminated at Auschwitz-Birkenau.[20][21][22]

The Germans operated a Nazi prison in the city with a forced labour subcamp in the present-day Karb district.[23] There were also multiple forced labour camps within the present-day city limits, including six subcamps of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp.[24] Dozens of prisoners were sent from the Nazi prison on a death march westwards towards Głubczyce.[25]

In January 1945, the city was captured by the Soviet Red Army. Soviet troops then committed massacres of civilians in the present-day district of Miechowice and Stolarzowice, killing some 400 and 70 people, respectively, and raped many women.[26] In 1945, the city was transferred to Poland as a result of the Potsdam Conference.[citation needed] Its German population was largely expelled by the Soviet Army and the remaining indigenous Polish inhabitants were joined mostly by Poles repatriated from the eastern provinces annexed by the Soviets.[citation needed]

In 2017, the Tarnowskie Góry Lead-Silver-Zinc Mine and its Underground Water Management System, located mostly in the neighboring city of Tarnowskie Góry, but also partly in Bytom, was included on the UNESCO World Heritage List.[27]

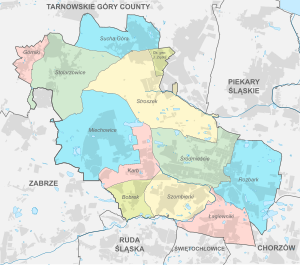

Districts

The city of Bytom is divided into 12 districts (Polish: Dzielnice), year of inclusion within the city limits in brackets:

- Śródmieście (lit. city centre/downtown)

- Rozbark (1927)

- Bobrek (1951)

- Karb (1951)

- Łagiewniki (1951)

- Miechowice (1951)

- Szombierki (1951)

- Górniki (1975)

- Osiedle gen. Jerzego Ziętka (1975), also known as Sójcze Wzgórze

- Stolarzowice (1975)

- Stroszek (1975)

- Sucha Góra (1975)

Radzionków with Rojca (currently a district of Radzionków) were located within the city limits of Bytom from 1975 until 1997. Somehow there is (probably) autonomic district named "Vitor" in South Stroszek.

Economy

Trade is one of the main pillars of the economy of Bytom. Being a city with long traditions of commercial trade, Bytom is fulfilling its new postindustrial role. In the centre of Bytom, and mainly around Station Street and the Market Square, is the largest concentration of registered merchants in the county.

In 2007, Bytom and its neighbours created the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union, the largest urban centre in Poland. The Union was superseded by Metropolis GZM in 2018.

Public transport

The tram routes are operated by Silesian Interurbans Tramwaje Śląskie S.A

Sport

Bytom is home to Polonia Bytom which has both a football and an ice hockey team (TMH Polonia Bytom). Its football team played in the Ekstraklasa, most recently from 2007 to 2011, winning it twice in 1954 and in 1962. The Szombierki district is home to another former Polish champion Szombierki Bytom which won the title in 1980, and is one of the oldest clubs in the region. Other areas of the city host football clubs such as Górniki which is home to lower league club Rodło Górniki, founded in 1946.[28]

Culture

Bytom's cultural venues include:

- Silesian Opera – ul. Moniuszki 21/23

- Miejska Biblioteka Publiczna w Bytomiu[29] (Town's Public Library)

- Dance Theatre Rozbark in Bytom

- Bytomskie Centrum Kultury[30] (Bytom Cultural Centre)

- Kronika – Center of modern art

- City Choir of St. Grzegorz Wielki

- Muzeum Górnośląskie (Upper Silesian Museum)

Among Bytom's art galleries are: Galeria Sztuki Użytkowej Stalowe Anioły, Galeria "Rotunda" MBP, Galeria "Suplement", Galeria "Pod Czaplą", Galeria "Platforma", Galeria "Pod Szrtychem", Galeria Sztuki "Od Nowa 2", Galeria SPAP "Plastyka" – Galeria "Kolor", Galeria "Stowarzyszenia.Rewolucja.Art.Pl", and Galeria-herbaciarnia "Fanaberia".

Festivals

- Annual International Contemporary Dance Conference and Performance Festival

- Theatromania – Theatre Festival

- Bytom Literary Autumn

- Festival of New Music

Education

- The list of Bytom universities includes:

- Silesian University of Technology – Faculty of Transport

- Medical University of Silesia

- Polish Japanese Institute of Information Technology

- Wyższa Szkoła Ekonomii i Administracji

- Secondary schools:

- I Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. Jana Smolenia

- II Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. Stefana Żeromskiego

- IV Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. Bolesława Chrobrego

- 21 other secondary schools

Politics

Bytom/Gliwice/Zabrze constituency

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected in the 2023 election from Bytom/Gliwice/Zabrze constituency

Notable people

- Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki (c. 1665–1734), Polish composer and musician

- Heinrich Schulz-Beuthen (1838–1915), German composer

- Siegfried Karfunkelstein (1848–1870), Prussian soldier

- Ernst Gaupp (1865–1916), German anatomist

- Ludwig Halberstädter (1876–1949), radiologist

- Adolf Kober (1879–1958), rabbi and historian

- Maximilian Kaller (1880–1947), bishop of Warmia

- Hermann Kober (1888-1973), Jewish-German mathematician

- Kate Steinitz (1889–1975), German-American artist and art historian

- Hartwig von Ludwiger (1895–1947), German general

- Max Tau (1897–1976), Jewish-German-Norwegian writer, editor and publisher

- Henry J. Leir (1900–1998), American industrialist, financier, and philanthropist

- Friedrich Domin (1902–1961), German film actor

- Herbert Büchs (1913–1996), German General

- Józef Kachel (1913–1983), head of the pre-war Polish Scouting Association in Germany

- Hans-Joachim Pancherz (1914–2008), German aviator and test pilot

- Horst Winter (1914–2001), German-Austrian jazz musician

- Leo Scheffczyk (1920–2005), German theologian and cardinal

- Bent Melchior(1929-2021) Chief Rabbi of Denmark and humanitarian.

- Haim Yavin (born 1932), Israeli news anchor

- Wolfgang Reichmann (1932–1991), German actor

- Reinhard Opitz (1934–1986), German political scientist

- Leo-Ferdinand Henckel von Donnersmarck (1935–2009), German businessman and Catholic lay worker

- Józef Szmidt (born 1935), Polish triple jumper

- Jan Liberda (1936–2020), Polish footballer

- Hans-Jochen Jaschke (1941-2023), German Roman Catholic bishop

- Jan Banaś (born 1943), Polish footballer

- Walter Winkler (1943–2014), Polish footballer

- Zygmunt Anczok (born 1946), Polish footballer

- Jerzy Konikowski (born 1947), chess player

- Leszek Engelking (born 1955), Polish poet, writer, translator and scholar

- Waldemar Legień (born 1963), Polish judoka, Olympic champion from Seoul and Barcelona

- Michał Probierz (born 1972), Polish football manager and former football player

- Marcin Suchański (born 1977), Polish footballer

- Marzena Godecki (born 1978), Australian actress

- Dorota Kobiela (born 1978), Polish filmmaker

- Paul Freier (born 1979), German footballer

- Marek Suker (born 1982), Polish footballer

- Gosia Andrzejewicz (born 1984), Polish pop singer

- Martyna Majok (born 1985), Polish-American playwright

- Weronika Murek (born 1989), Polish writer

- Mariusz Wodzicki, Polish mathematician

Twin towns – sister cities

Gallery

-

Bobrek power station in the 1930s

-

Market square

-

Bytom city hall

-

St. Hyacinth's Church – an example of Neo-Romantic architecture in Bytom

-

Plac Akademicki – public square

-

Holy Trinity Church

-

IV Secondary School

References

- ^ "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved June 2, 2022. Data for territorial unit 2462011.

- ^ "Bytom (śląskie) » mapy, nieruchomości, GUS, noclegi, szkoły, regon, atrakcje, kody pocztowe, wypadki drogowe, bezrobocie, wynagrodzenie, zarobki, tabele, edukacja, demografia".

- ^ "Demographic and occupational structure and housing conditions of the urban population in 1978-1988" (PDF).

- ^ "Statistics Poland - National Censuses".

- ^ J. Kramer, Chronik der Stadt Beuthen in Ober-Schlesien, Bytom, 1863, p. 1

- ^ Roman Majorczyk, Historia górnictwa kruszcowego w rejonie Bytomia, Bytom, 1985, p. 9

- ^ Paweł Freus. "Jan III Sobieski na Śląsku w drodze na odsiecz Wiedniowi roku 1683". Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie (in Polish). Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Pater, Mieczysław (1963). "Wrocławskie echa powstania styczniowego". Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka (in Polish) (4): 418.

- ^ Belzyt, Leszek (1998). Sprachliche Minderheiten im preussischen Staat: 1815 - 1914 ; die preußische Sprachenstatistik in Bearbeitung und Kommentar. Marburg: Herder-Inst. ISBN 978-3-87969-267-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Aktuelle News, Schlagzeilen und Berichte aus aller Welt - Arcor.de". www.arcor.de. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Sebastian; Węcki, Mirosław (2010). Nadzorować, interweniować, karać. Nazistowski obóz władzy wobec Kościoła katolickiego w Zabrzu (1934–1944). Wybór dokumentów (in Polish). Katowice: IPN. p. 306. ISBN 978-83-8098-299-4.

- ^ Cygański, Mirosław (1984). "Hitlerowskie prześladowania przywódców i aktywu Związków Polaków w Niemczech w latach 1939 - 1945". Przegląd Zachodni (in Polish) (4): 31, 33.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Węcki, p. 60

- ^ Cygański, p. 24

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 78.

- ^ Cygański, p. 32

- ^ Cygański, p. 33

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 58.

- ^ Cygański, p. 63

- ^ Jews deported from Beuthen (Bytom), list prepared in 1942 Archived 15 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Elsa Drezner, Yizkor Book Project Manager Avraham Groll, Names of Jews deported from Beuthen Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Translations: deportation Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Zuchthaus Beuthen". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ "Working Parties". Stalag VIIIB 344 Lamsdorf. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Konieczny, Alfred (1974). "Więzienie karne w Kłodzku w latach II wojny światowej". Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka (in Polish). XXIX (3). Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk: 377.

- ^ Hanich, Andrzej (2012). "Losy ludności na Śląsku Opolskim w czasie działań wojennych i po wejściu Armii Czerwonej w 1945 roku". Studia Śląskie (in Polish). LXXI. Opole: 217. ISSN 0039-3355.

- ^ "Tarnowskie Góry Lead-Silver-Zinc Mine and its Underground Water Management System". UNESCO. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ "Historia". rodlogorniki.klubowo24.pl (in Polish). Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "Home". biblioteka.bytom.pl.

- ^ DESIGN, ARF. "Bytomskie Centrum Kultury". www.becek.pl.

- ^ "Miasta partnerskie". bytom.pl (in Polish). Bytom. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

External links

- Municipality of Bytom Archived January 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine