Camera trap

A camera trap is a camera that is automatically triggered by motion in its vicinity, like the presence of an animal or a human being. It is typically equipped with a motion sensor – usually a passive infrared (PIR) sensor or an active infrared (AIR) sensor using an infrared light beam.[1]

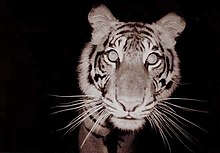

Camera traps are a type of remote cameras used to capture images of wildlife with as little human interference as possible.[1] Camera trapping is a method for recording wild animals when researchers are not present, and has been used in ecological research for decades. In addition to applications in hunting and wildlife viewing, research applications include studies of nest ecology, detection of rare species, estimation of population size and species richness, and research on habitat use and occupation of human-built structures.[2]

Since the introduction of commercial infrared-triggered cameras in the early 1990s, their use has increased.[3] With advancements in the quality of camera equipment, this method of field observation has become more popular among researchers.[4] Hunting has played an important role in development of camera traps, since hunters use them to scout for game.[5] These hunters have opened a commercial market for the devices, leading to many improvements over time.

Application

The great advantage of camera traps is that they can record very accurate data without disturbing the photographed animal. These data are superior to human observations because they can be reviewed by other researchers.[2] They minimally disturb wildlife and can replace the use of more invasive survey and monitoring techniques such as live trap and release. They operate continually and silently, provide proof of species present in an area, can reveal what prints and scats belong to which species, provide evidence for management and policy decisions, and are a cost-effective monitoring tool. Infrared flash cameras have low disturbance and visibility.[6] Besides olfactory and acoustic cues, camera flash may scare animals so that they avoid or destroy camera traps. The major alternative light source is infrared, which is usually not detectable by mammals or birds.[2]

Camera traps are also helpful in quantifying the number of different species in an area; this is a more effective method than attempting to count by hand every individual organism in a field. It can also be useful in identifying new or rare species that have yet to be well documented. It has been key in recent years in the rediscovery of species such as the black-naped pheasant-pigeon, thought to be extinct for 140 years but captured on a trail camera by researchers.[7] By using camera traps, the well-being and survival rate of animals can be observed over time.[8]

Camera traps are helpful in determining behavioral and activity patterns of animals, such as which time of day they visit mineral licks.[9] Camera traps are also useful to record animal migrations.[10][11][12]

Camera types

The earliest models used traditional film and a one-shot trigger function. These cameras contained film that needed to be collected and developed like any other standard camera. Today, more advanced cameras utilize digital photography, sending photos directly to a computer. Even though this method is uncommon, it is highly useful and could be the future of this research method. Some cameras are even programmed to take multiple pictures after a triggering event.[13]

There are non-triggered cameras that either run continuously or take pictures at specific time intervals. The more common ones are the advanced cameras that are triggered only after sensing movement and/or a heat signature to increase the chances of capturing a useful image. Infrared beams can also be used to trigger the camera. Video is also an emerging option in camera traps, allowing researchers to record running streams of video and to document animal behavior.

The battery life of some of these cameras is another important factor in which cameras are used; large batteries offer a longer running time for the camera but can be cumbersome in set up or when lugging the equipment to the field site.[8]

Extra features

Weather proof and waterproof housing for camera traps protect the equipment from damage and disguise the equipment from animals.[14]

Noise-reduction housing limits the possibility of disturbing and scaring away animals. Sound recording is another feature that can be added to the camera to record animal calls and times when specific animals are the most vocal.[1]

Wireless transmission allows images and videos to be sent using cellular networks, so users can view activity instantly without disturbing their targets.

The use of invisible flash "No-Glow" IR leverages 940 nm infrared waves to illuminate a night image without being detected by humans or wildlife. These waves are outside of the visible light spectrum so the subject doesn't know they are being watched.

Effects of weather and the environment

Humidity has a highly negative effect on camera traps and can result in camera malfunction. This can be problematic since the malfunction is often not immediately discovered, so a large portion of research time can be lost.[6] Often a researcher expecting the experiment to be complete will trek back to the site, only to discover far less data than expected – or even none at all.[13]

The best type of weather for it to work in is any place with low humidity and stable moderate temperatures. There is also the possibility, if it is a motion activated camera, that any movement within the sensitivity range of the camera’s sensor will trigger a picture, so the camera might end up with numerous pictures of anything the wind moves, such as plants.

As far as problems with camera traps, it cannot be overlooked that sometimes the subjects themselves negatively affect the research. One of the most common things is that animals unknowingly topple a camera or splatter it with mud or water ruining the film or lens. One other method of animal tampering involves the animals themselves taking the cameras for their own uses. There are examples of some animals actually taking the cameras and snapping pictures of themselves.[13]

Local people sometimes use the same game trails as wildlife, and hence are also photographed by camera traps placed along these trails. This can make camera traps a useful tool for anti-poaching or other law enforcement effort.

Placement techniques

One of the most important things to consider when setting up camera traps is choosing the location in order to get the best results. Camera traps near mineral licks or along game trails, where it is more likely that animals will visit frequently, are normally seen. Animals congregate around a mineral lick to consume water and soil, which can be useful in reducing toxin levels or supplement mineral intake in their diet. These locations for camera traps also allow for variety of animals who show up at different times and use the licks in different ways allowing for the study of animal behavior.[8]

To study more specific behaviors of a particular species, it is helpful to identify the target species' runs, dens, beds, latrines, food caches, favored hunting and foraging grounds, etc. Knowledge of the target species' general habits, seasonal variations in behavior and habitat use, as well as its tracks, scat, feeding sign, and other spoor are extremely helpful in locating and identifying these sites, and this strategy has been described in great detail for many species.[15]

Bait may be used to attract desired species. However type, frequency and method of presentation require careful consideration.[16]

Another major factor in whether this is the best technique to use in the specific research is which type of species one is attempting to observe with the camera. Species such as small-bodied birds and insects may be too small to trigger the camera. Reptiles and amphibians will not be able to trip the infrared or heat differential-based sensors, however, methods have been developed to detect these species by utilizing a reflector based sensor system. However, for most medium and large-bodied terrestrial species camera traps have proven to be a successful tool for study.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "WWF - Camera Traps - More on Camera Traps". World Wildlife Fund - Wildlife Conservation, Endangered Species Conservation. World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Swann, D. E., Kawanishi, K., Palmer, J. (2010). "Evaluating Types and Features of Camera Traps in Ecological Studies: A Guide for Researchers". In O'Connell, A. F.; Nichols, J. D., Karanth, U. K. (eds.). Camera Traps in Animal Ecology: Methods and Analyses. Tokyo, Dordrecht, London, Heidelberg, New York: Springer. pp. 27–43. ISBN 978-4-431-99494-7. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meek, P.; Fleming, P., eds. (2014). Camera Trapping. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486300396. Archived from the original on 2023-11-10. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ "Camera Traps for Researchers, Camera Trap Reviews and Tests". Trail Cameras, Game Cameras Tests and Unbiased Reviews of Camera Traps. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Jiao, H. (2014). "Wireless Trail Cameras". Trail Camera Lab. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ a b Cronin, S. (2010). "Camera trap talk" (PDF). Photographic Society, April 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kobilinsky, Dana (2022-11-21). "Watch: Rare bird recorded after 140 year-absence to science". The Wildlife Society. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ a b c "A-Z Animal Index". Smithsonian Wild. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Blake, J. G.; Guerra, J.; Mosquera, D.; Torres, R.; Loiselle, B. A.; Romo, D. (2010). "Use of Mineral Licks by White-Bellied Spider Monkeys (Ateles belzebuth) and Red Howler Monkeys (Alouatta seniculus) in Eastern Ecuador" (PDF). Internal Journal of Primatology. 31 (3): 471–483. doi:10.1007/s10764-010-9407-5. S2CID 23419485. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2019.

- ^ "How a Photographer Captured Stunning Wildlife Photos". video.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-02. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- ^ Hance, J. (2011). "Camera Traps Emerge as Key Tool in Wildlife Research". Yale Environment 360. New Haven: Yale University. Archived from the original on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ Anton, Alex. "live london camera". Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d O'Connell, A. F., Nichols, J. D., Karanth, U. K. (Eds.) (2010). Camera Traps in Ecology: Methods and Analyses. Tokyo, Dordrecht, London, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Griffiths, M.; van Schaik, C. P. (1993). "Camera-trapping: a new tool for the study of elusive rain forest animals". Tropical Biodiversity. 1: 131–135.

- ^ Pesaturo, Janet (2018). Camera Trapping Guide: Tracks, Sign, and Behavior of Eastern Wildlife. Guilford: Stackpole Books. pp. 1–264. ISBN 978-0811719063.

- ^ Delaney, D.K.; Leitner, P; Hacker, D. "Use of Camera Traps in Mohave Ground Squirrel Studies". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

Further reading

- Rovero, Francesco; Zimmermann, Fridolin (2016). Camera Trapping for Wildlife Research. Exeter: Pelagic Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78427-048-3.

- Pesaturo, Janet (2018). Camera Trapping Guide: Tracks, Sign, and Behavior of Eastern Wildlife. Guilford: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0811719063.

- Kays, Roland (2016). Candid Creatures: How Camera Traps Reveal the Mysteries of Nature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421418889.

- Where birdwatching and artificial intelligence collide

- Using AI to Monitor Wildlife Cameras at Springwatch