Francis Langley

Francis Langley (1548–1602) was a theatre builder and theatrical producer in Elizabethan era London.[1] After James Burbage and Philip Henslowe, Langley was the third significant entrepreneurial figure active at the height of the development of English Renaissance theatre.[2][3]

Background

Langley was a goldsmith by profession, and also held the office of "Alnager and Searcher of Cloth" – he was an official quality inspector of fabric. His brother-in-law was a clerk for the Privy Council; Langley had been appointed to his Alnager's post through a recommendation from Sir Francis Walsingham. Langley became involved in theatre in the mid-1590s, and operated much as Henslowe did,[4] contracting individual actors and troupes to work exclusively for him, and serving as their reliable creditor. Langley, however, did not leave the relatively abundant documentary record that Henslowe did; his affairs are much more mysterious and difficult to untangle.

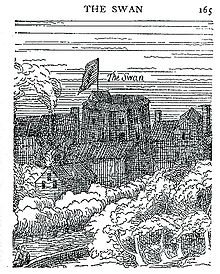

Swan Theatre

Langley's central achievement in Elizabethan drama was the building of the Swan Theatre in Southwark, on the south shore of the River Thames across from the City of London, in 1595–96.[5][6] The Swan was the fourth large public playhouse in London, after Burbage's The Theatre (1576), Lanman's Curtain (1577) and Henslowe's Rose (1587) – though the Swan was in its time the most well-appointed and visually striking of the four. Langley had purchased the Manor of Paris Garden as early as May 1589, for the sum of £850. (Paris Garden was a "liberty," at the extreme western end of the Bankside district of Southwark. The Manor in question had been part of the monastery of Bermondsey, which, like all such establishments in England, had passed into private hands after Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. In November 1594, the Lord Mayor of London complained to Lord Burghley about Langley's plans to build another theatre on the Bankside.[7] The Rose and the Beargarden, the bear-baiting ring, were already located there.

The Lord Mayor's protest had no discernible effect; the Swan was certainly ready by February 1597, when Langley signed a contract with Pembroke's Men to play at his new theatre. Their contract mentions that the theatre had already been in use for plays, which points to activity in the summer of 1596. The playing company involved is not named; but given Shakespeare's odd connection with Langley (see below), it might have been the Lord Chamberlain's Men.

Shakespeare and dispute with Gardiner

Langley also had an unknown connection with William Shakespeare. In November 1596 two writs of attachment, similar to modern restraining orders, were issued to the sheriff of Surrey, the shire in which Southwark is located. First, Langley took out a writ against two parties named William Gardiner and William Wayte; William Wayte then took out a writ against William Shakespeare, Langley, and two women named Anne Lee and Dorothy Soer.

William Gardiner was a corrupt Surrey justice of the peace. Leslie Hotson describes Gardiner's life as a tissue of "greed, usury, fraud, cruelty and perjury".[8] Shortly before these events he had brought charges of slander against Langley, for having accused him of perjury. Langley defended himself robustly, insisting that the accusation was true and he could prove it in court. Gardiner dropped the charges.[8] William Wayte was Gardiner's stepson, described in another document as "a certain loose person of no reckoning or value being wholly under the rule and commandment of said Gardiner".[8]

Shakespeare's role in this dispute is unclear. Anne Lee and Dorothy Soer, the two women named with Shakespeare in the second writ, cannot be identified. Hotson assumes they worked at the theatre in a support capacity. Shakespeare may have been connected with Langley through the Pembroke's Men, with whom he probably worked in the early 1590s, since they played at least two of his earliest works, Titus Andronicus and Henry VI, Part 3; his later company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, may have acted a season at the Swan in the summer of 1596. He appears to have been living in the area at the time. Hotson argues that a dispute of some sort between Langley and Gardiner probably escalated after Gardiner's bluff was called over the slander charges. He believes that Gardiner took his revenge by threatening Langley's theatre interests, persecuting "Langley and Shakespeare and his fellow actors at the Swan" with the support of Puritan opponents of the theatre.[8] This may have involved threats to destroy the theatre itself, since Gardiner obtained an order to demolish Langley's theatre some months after the writs were issued, though the order was soon rescinded. The luckless Wayte, as Gardiner's agent, would have been on the receiving end of the backlash from supporters of the theatre, probably leading to altercations of some sort. The feud ended with Gardiner's death in November 1597.

The Isle of Dogs

If there was a period of good business in the spring and summer of 1597, it definitely did not last: in July came the scandal centred on Thomas Nashe and Ben Jonson's play The Isle of Dogs. On 28 July the Privy Council, angered by what it termed "very seditious and scandalous matter" in that play, ordered all the London theatres shut down for the remainder of the summer. When the prohibition on the other theatres was lifted in the autumn, it was kept on Langley's Swan, dealing his theatre business a serious blow. Langley was in trouble with the authorities over another matter as well, a stolen diamond that he had fenced or attempted to fence; and this may well have been an additional reason for the suppression of his theatre.

Five of the actors in Pembroke's Men, now out of work, defected to the Admiral's Men, and apparently took some of the company's playscripts with them. Langley sued them, though the outcome of the case is unclear from the surviving records.[9] It seems likely that Langley reached some kind of resolution with Henslowe, for the actors remained with their new company. Langley's position at this time could not have been a strong one. The remnant of the Pembroke's Men company, perhaps with some replacement members, was touring outside London in 1598–99, in Bath, Bristol, Dover, and other towns.

Boar's Head

His harsh experience with the Swan Theatre did not entirely sour Langley on the business of drama. The Boar's Head Inn, outside the City of London's medieval walls on the northeast, had long been a venue for play-acting in previous decades; it was converted to a theatre in 1598 by a partnership between Oliver Woodliffe and Richard Samwell. In November of that year, however, Langley bought Woodliffe's share in the concern. The original conversion proved unsatisfactory, and a major reconstruction was launched in 1599. At the same time the litigious Langley launched a series of lawsuits against Samwell concerning the costs of refitting the theatre – a legal campaign that ended with Langley's death early in 1602.[10] However, the Boar's Head never succeeded as a theatre, and the project failed after 1604.

Death and legacy

After Langley's own death in January 1602, his Paris Garden estate was sold. His theatre lived on after him, hosting miscellaneous events – fencing contests, boxing matches, stage-magic spectacles – and eventually becoming a venue for drama once again; the Lady Elizabeth's Men played at the Swan in the 1611–13 period. They acted Thomas Middleton's A Chaste Maid in Cheapside there in 1613. Eventually the place fell into disrepair; a 1632 pamphlet refers to the building as "fallen to decay, and like a dying swan hanging down her head, seemed to sing her own dirge."

References

- ^ William Ingram, A London Life in the Brazen Age: Francis Langley, 1548–1602, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1978.

- ^ F. E. Halliday A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 273.

- ^ Andrew Gurr, The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642, Third edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992; pp. 42–5 and ff.

- ^ E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 1, p. 368 n. 3.

- ^ Chambers, Vol. 2, pp. 411–14.

- ^ Halliday, p. 481.

- ^ Chambers, Vol 4, pp. 316–17.

- ^ a b c d Leslie Hoson, Shakespeare versus Swallow, 1931, p. 24-30.

- ^ Chambers, Vol. 2, pp. 131–3.

- ^ Gurr, pp. 139–40.