Gurmukhi

| Gurmukhī ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ | |

|---|---|

Modern Gurmukhi letter set | |

| Script type | |

Time period | 16th century CE-present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Anandpur Lipi |

Sister systems | Khudabadi, Khojki, Mahajani, Multani |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Guru (310), Gurmukhi |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Gurmukhi |

| U+0A00–U+0A7F | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Gurmukhī (ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ, Punjabi pronunciation: [ˈɡʊɾᵊmʊkʰiː]) is an abugida developed from the Laṇḍā scripts, standardized and used by the second Sikh guru, Guru Angad (1504–1552).[2][1] Commonly regarded as a Sikh script,[3][4][5][6][7] Gurmukhi is used in Punjab, India as the official script of the Punjabi language.[6][7]

The primary scripture of Sikhism, the Guru Granth Sahib, is written in Gurmukhī, in various dialects and languages often subsumed under the generic title Sant Bhasha[8] or "saint language", in addition to other languages like Persian and various phases of Indo-Aryan languages.

Modern Gurmukhī has thirty-five original letters, hence its common alternative term paintī or "the thirty-five",[6] plus six additional consonants,[6][9][10] nine vowel diacritics, two diacritics for nasal sounds, one diacritic that geminates consonants and three subscript characters.

History and development

The Gurmukhī script is generally believed to have roots in the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet[11] by way of the Brahmi script,[12] which developed further into the Northwestern group (Sharada, or Śāradā, and its descendants, including Landa and Takri), the Central group (Nagari and its descendants, including Devanagari, Gujarati and Modi) and the Eastern group (evolved from Siddhaṃ, including Bangla, Tibetan, and some Nepali scripts),[13] as well as several prominent writing systems of Southeast Asia and Sinhala in Sri Lanka, in addition to scripts used historically in Central Asia for extinct languages like Saka and Tocharian.[13] Gurmukhi is derived from Sharada in the Northwestern group, of which it is the only major surviving member,[14] with full modern currency.[15] Notable features include:

- It is an abugida in which all consonants have an inherent vowel, [ə]. Diacritics, which can appear above, below, before or after the consonant they are applied to, are used to change the inherent vowel.

- When they appear at the beginning of a syllable, vowels are written as independent letters.

- To form consonant clusters, Gurmukhi uniquely affixes subscript letters at the bottom of standard characters, rather than using the true conjunct symbols used by other scripts,[15] which merge parts of each letter into a distinct character of its own.

- Punjabi is a tonal language with three tones. These are indicated in writing using the formerly voiced aspirated consonants (gh, dh, bh, etc.) and the intervocalic h.[16]

| Phoenician | 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aramaic | 𐡀 | 𐡁 | 𐡂 | 𐡃 | 𐡄 | 𐡅 | 𐡆 | 𐡇 | 𐡈 | 𐡉 | 𐡊 | 𐡋 | 𐡌 | 𐡍 | 𐡎 | 𐡏 | 𐡐 | 𐡑 | 𐡒 | 𐡓 | 𐡔 | 𐡕 | ||||||||||||||

| Brahmi | 𑀅 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀕 | 𑀥 | 𑀠 | 𑀏 | 𑀯 | 𑀤 | 𑀟 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀳 | 𑀖 | 𑀣 | 𑀞 | 𑀬 | 𑀓 | 𑀘 | 𑀮 | 𑀫 | 𑀦 | 𑀗 | 𑀜 | 𑀡 | 𑀰 | 𑀑 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀲 | 𑀔 | 𑀙 | 𑀭 | 𑀱 | 𑀢 | 𑀝 |

| Gurmukhi | ਅ | ਬ | ਭ | ਗ | ਧ | ਢ | ੲ | ਵ | ਦ | ਡ | ਜ | ਝ | ਹ | ਘ | ਥ | ਠ | ਯ | ਕ | ਚ | ਲ | ਮ | ਨ | ਙ | ਞ | ਣ | (ਸ਼) | ੳ | ਪ | ਫ | ਸ | ਖ | ਛ | ਰ | ਖ | ਤ | ਟ |

| IAST | a | ba | bha | ga | dha | ḍha | ē | va | da | ḍa | ja | jha | ha | gha | tha | ṭha | ya | ka | ca | la | ma | na | ṅa | ña | ṇa | śa* | ō | pa | pha | sa | kha | cha | ra | ṣa* | ta | ṭa |

| Greek | Α | Β | Γ | Δ | Ε | Ϝ | Ζ | Η | Θ | Ι | Κ | Λ | Μ | Ν | Ξ | Ο | Π | Ϻ | Ϙ | Ρ | Σ | Τ | ||||||||||||||

| Possible derivation of Gurmukhi from earlier writing systems.[17][note 1] The Greek alphabet, also descended from Phoenician, is included for comparison. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gurmukhi evolved in cultural and historical circumstances notably different from other regional scripts,[14] for the purpose of recording scriptures of Sikhism, a far less Sanskritized cultural tradition than others of the subcontinent.[14] This independence from the Sanskritic model allowed it the freedom to evolve unique orthographical features.[14] These include:

- Three basic bearer vowels, integrated into the traditional Gurmukhi character set, using the vowel diacritics to write independent vowels, instead of distinctly separate characters for each of these vowels as in other scripts;[16][18]

- a drastic reduction in the number and importance of conjunct characters[16][19][1] (similar to Brahmi, the letters of which Gurmukhi letters have remained more similar to than those of Nagari have,[20] and characteristic of Northwestern abugidas);[15]

- a unique standard ordering of characters that somewhat diverges from the traditional vargiya, or Sanskritic, ordering of characters,[16][21] including vowels and fricatives being placed in front;[22][23]

- the recognition of Indo-Aryan phonological history through the omission of characters representing the sibilants [ʃ] and [ʂ],[24] retaining only the letters representing sounds of the spoken language of the time;[1] these sibilants were naturally lost in most modern Indo-Aryan languages, though such characters were often retained in their respective consonant inventories as placeholders and archaisms[16] while being mispronounced.[24] These sibilants were often variously reintroduced through later circumstances, as [ʃ] was to Gurmukhi,[23] necessitating a new glyph;[24]

- the development of distinct new letters for sounds better reflecting the vernacular language spoken during the time of its development (e.g. for [ɽ],[25] and the sound shift that merged Sanskrit [ʂ] and /kʰ/ to Punjabi /kʰ/);

- a gemination diacritic, a unique feature among native subcontinental scripts,[14] which serve to indicate the preserved Middle Indo-Aryan geminates distinctive of Punjabi;[15]

and other features.

From the 10th century onwards, regional differences started to appear between the Sharada script used in Punjab, the Hill States (partly Himachal Pradesh) and Kashmir. Sharada proper was eventually restricted to very limited ceremonial use in Kashmir, as it grew increasingly unsuitable for writing the Kashmiri language.[26] With the last known inscription dating to 1204 C.E., the early 13th century marks a milestone in the development of Sharada.[26] The regional variety in Punjab continued to evolve from this stage through the 14th century; during this period it starts to appear in forms closely resembling Gurmukhī and other Landa scripts. By the 15th century, Sharada had evolved so considerably that epigraphists denote the script at this point by a special name, Dēvāśēṣa.[26] Tarlochan Singh Bedi (1999) prefers the name prithamă gurmukhī, or Proto-Gurmukhī. It was through its recording in Gurmukhi that knowledge of the pronunciation and grammar of the Old Punjabi language (c. 10th–16th century) was preserved for modern philologists.[27]

The Sikh gurus adopted Proto-Gurmukhī to write the Guru Granth Sahib, the religious scriptures of the Sikhs. The Takri alphabet developed through the Dēvāśēṣa stage of the Sharada script from the 14th-18th centuries[26] and is found mainly in the Hill States such as Chamba, Himachal Pradesh and surrounding areas, where it is called Chambeali. In Jammu Division, it developed into Dogri,[26] which was a "highly imperfect" script later consciously influenced in part by Gurmukhi during the late 19th century,[28] possibly to provide it an air of authority by having it resemble scripts already established in official and literary capacities,[29] though not displacing Takri.[28] The local Takri variants got the status of official scripts in some of the Punjab Hill States, and were used for both administrative and literary purposes until the 19th century.[26] After 1948, when Himachal Pradesh was established as an administrative unit, the local Takri variants were replaced by Devanagari.

Meanwhile, the mercantile scripts of Punjab known as the Laṇḍā scripts were normally not used for literary purposes. Laṇḍā means alphabet "without tail",[15] implying that the script did not have vowel symbols. In Punjab, there were at least ten different scripts classified as Laṇḍā, Mahajani being the most popular. The Laṇḍā scripts were used for household and trade purposes.[31] In contrast to Laṇḍā, the use of vowel diacritics was made obligatory in Gurmukhī for increased accuracy and precision, due to the difficulties involved in deciphering words without vowel signs.[1][32]

In the following epochs, Gurmukhī became the primary script for the literary writings of the Sikhs. Playing a significant role in Sikh faith and tradition, it expanded from its original use for Sikh scriptures and developed its own orthographical rules, spreading widely under the Sikh Empire and used by Sikh kings and chiefs of Punjab for administrative purposes.[22] Also playing a major role in consolidating and standardizing the Punjabi language, it served as the main medium of literacy in Punjab and adjoining areas for centuries when the earliest schools were attached to gurdwaras.[22] The first natively produced grammars of the Punjabi language were written in the 1860s in Gurmukhi.[33] The Singh Sabha Movement of the late 19th century, a movement to revitalize Sikh institutions which had declined during colonial rule after the fall of the Sikh Empire, also advocated for the usage of the Gurmukhi script for mass media, with print media publications and Punjabi-language newspapers established in the 1880s.[34] Later in the 20th century, after the struggle of the Punjabi Suba movement, from the founding of modern India in the 1940s to the 1960s, the script was given the authority as the official state script of the Punjab, India,[6][7] where it is used in all spheres of culture, arts, education, and administration, with a firmly established common and secular character.[22] It is one of the official scripts of the Indian Republic, and is currently the 14th most used script in the world.[35]

Etymology

The prevalent view among Punjabi linguists is that as in the early stages the Gurmukhī letters were primarily used by the Guru's followers, gurmukhs (literally, those who face, or follow, the Guru, as opposed to a manmukh); the script thus came to be known as gurmukhī, "the script of those guided by the Guru."[14][36] Guru Angad is credited in the Sikh tradition with the creation and standardization of Gurmukhi script from earlier Śāradā-descended scripts native to the region. It is now the standard writing script for the Punjabi language in India.[37] The original Sikh scriptures and most of the historic Sikh literature have been written in the Gurmukhi script.[37]

Although the word Gurmukhī has been commonly translated as "from the Mouth of the Guru", the term used for the Punjabi script has somewhat different connotations. This usage of the term may have gained currency from the use of the script to record the utterances of the Sikh Gurus as scripture, which were often referred to as Gurmukhī, or from the mukhă (face, or mouth) of the Gurus. Consequently, the script that was used to write the resulting scripture may have also been designated with the same name.[1]

The name for the Perso–Arabic alphabet for the Punjabi language, Shahmukhi, was modeled on the term Gurmukhi.[38][39]

Characters

Letters

The Gurmukhī alphabet contains thirty-five base letters (akkhară), traditionally arranged in seven rows of five letters each. The first three letters, or mātarā vāhakă ("vowel bearer"), are distinct because they form the basis for independent vowels and are not consonants, or vianjană, like the remaining letters are, and except for the second letter aiṛā[note 2] are never used on their own;[31] see § Vowel diacritics for further details. The pair of fricatives, or mūlă vargă ("base class"), share the row, which is followed by the next five sets of consonants, with the consonants in each row being homorganic, the rows arranged from the back (velars) to the front (labials) of the mouth, and the letters in the grid arranged by place and manner of articulation.[40] The arrangement, or varṇămāllā,[40] is completed with the antimă ṭollī, literally "ending group." The names of most of the consonants are based on their reduplicative phonetic values,[22] and the varṇămāllā is as follows:[6]

| Group Name (Articulation) ↓ |

Name | Sound [IPA] |

Name | Sound [IPA] |

Name | Sound [IPA] |

Name | Sound [IPA] |

Name | Sound [IPA] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mātarā vāhakă (Vowels) |

mūlă vargă (Fricatives) |

ੳ | ūṛā [uːɽaː] |

– | ਅ | aiṛā [ɛːɽaː] |

a [ə] |

ੲ | īṛī [iːɽiː] |

– | ਸ | sassā [səsːaː] |

sa [s] |

ਹ | hāhā [ɦaːɦaː] |

ha [ɦ] |

| Occlusives → | Tenuis | Aspirates | Voiced Stops | Tonal | Nasals | |||||||||||

| kavargă ṭollī (Velars) |

ਕ | kakkā [kəkːaː] |

ka [k] |

ਖ | khakkhā [kʰəkʰːaː] |

kha [kʰ] |

ਗ | gaggā [gəgːaː] |

ga [ɡ] |

ਘ | kàggā [kə̀gːaː] |

kà [ kə̀ ] |

ਙ | ṅaṅṅā [ŋəŋːaː] |

ṅa [ŋ] | |

| cavargă ṭollī (Affricates/Palatals) |

ਚ | caccā [t͡ʃət͡ʃːaː] |

ca [t͡ʃ] |

ਛ | chacchā [t͡ʃʰət͡ʃʰːaː] |

cha [t͡ʃʰ] |

ਜ | jajjā [d͡ʒəd͡ʒːaː] |

ja [d͡ʒ] |

ਝ | càjjā [t͡ʃə̀d͡ʒːaː] |

cà [ t͡ʃə̀ ] |

ਞ | ñaññā [ɲəɲːaː] |

ña [ɲ] | |

| ṭavargă ṭollī (Retroflexes) |

ਟ | ṭaiṅkā [ʈɛŋkaː] |

ṭa [ʈ] |

ਠ | ṭhaṭṭhā [ʈʰəʈʰːaː] |

ṭha [ʈʰ] |

ਡ | ḍaḍḍā [ɖəɖːaː] |

ḍa [ɖ] |

ਢ | ṭàḍḍā [ʈə̀ɖːaː] |

ṭà [ ʈə̀ ] |

ਣ | nāṇā [naːɳaː] |

ṇa [ɳ] | |

| tavargă ṭollī (Dentals) |

ਤ | tattā [t̪ət̪ːaː] |

ta [t̪] |

ਥ | thatthā [t̪ʰət̪ʰːaː] |

tha [t̪ʰ] |

ਦ | daddā [d̪əd̪ːaː] |

da [d̪] |

ਧ | tàddā [t̪ə̀d̪ːaː] |

tà [ t̪ə̀ ] |

ਨ | nannā [nənːaː] |

na [n] | |

| pavargă ṭollī (Labials) |

ਪ | pappā [pəpːaː] |

pa [p] |

ਫ | phapphā [pʰəpʰːaː] |

pha [pʰ] |

ਬ | babbā [bəbːaː] |

ba [b] |

ਭ | pàbbā [pə̀bːaː] |

pà [ pə̀ ] |

ਮ | mammā [məmːaː] |

ma [m] | |

| Approximants and liquids | ||||||||||||||||

| antimă ṭollī (Sonorants) |

ਯ | yayyā [jəjːaː] |

ya [j] |

ਰ | rārā [ɾaːɾaː] |

ra [ɾ]~[r] |

ਲ | lallā [ləlːaː] |

la [l] |

ਵ | vāvā [ʋaːʋaː] |

va [ʋ]~[w] |

ੜ | ṛāṛā [ɽaːɽaː] |

ṛa [ɽ] | |

The nasal letters ਙ ṅaṅṅā and ਞ ñaññā have become marginal as independent consonants in modern Gurmukhi.[41] The sounds they represent occur most often as allophones of [n] in clusters with velars and palatals respectively.[42][note 3]

The pronunciation of ਵ can vary allophonically between [[ʋ] ~ [β]] preceding front vowels, and [[w]] elsewhere.[44][45]

The most characteristic feature of the Punjabi language is its tone system.[6] The script has no separate symbol for tones, but they correspond to the tonal consonants that once represented voiced aspirates as well as older *h.[6] To differentiate between consonants, the Punjabi tonal consonants of the fourth column, ਘ kà, ਝ cà, ਢ ṭà, ਧ tà, and ਭ pà, are often transliterated in the way of the voiced aspirate consonants gha, jha, ḍha, dha, and bha respectively, although Punjabi lacks these sounds.[46] Tones in Punjabi can be either rising, neutral, or falling:[6][47]

- When the tonal letter is in onset positions, as in the pronunciation of the names of the Gurmukhī letters, it produces the falling tone on the syllable nucleus, indicated by a grave accent (◌̀).

- When the tonal letter is in syllabic coda positions, the tone on the syllable nucleus is rising, indicated by an acute accent (◌́).

- When the tonal letter is in intervocalic positions, after a short vowel and before a long vowel, the following vowel has a falling tone.[6][48] Between two short vowels, the tonal letter produces a rising tone on the preceding vowel.

The letters now always represent unaspirated consonants, and are unvoiced in onset positions and voiced elsewhere.[6]

Supplementary letters

In addition to the 35 original letters, there are six supplementary consonants in official usage,[6][9][10] referred to as the navīnă ṭollī[9][10] or navīnă vargă, meaning "new group", created by placing a dot (bindī) at the foot (pairă) of the consonant to create pairĭ bindī consonants. These are not present in the Guru Granth Sahib or old texts. These are used most often for loanwords,[6] though not exclusively,[note 4] and their usage is not always obligatory:

| Name | Sound [IPA] |

Name | Sound [IPA] |

Name | Sound [IPA] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ਸ਼ | sassē pairĭ bindī [səsːeː pɛ:ɾɨ bɪn̪d̪iː] |

śa [ʃ] |

ਖ਼ | khakkhē pairĭ bindī [kʰəkʰːeː pɛ:ɾɨ bɪn̪d̪iː] |

xa [x] |

ਗ਼ | gaggē pairĭ bindī [gəgːeː pɛ:ɾɨ bɪn̪d̪iː] |

ġa [ɣ] |

| ਜ਼ | jajjē pairĭ bindī [d͡ʒəd͡ʒːeː pɛ:ɾɨ bɪn̪d̪iː] |

za [z] |

ਫ਼ | phapphē pairĭ bindī [pʰəpʰːeː pɛ:ɾɨ bɪn̪d̪iː] |

fa [f] |

ਲ਼ | lallē pairĭ bindī [ləlːeː pɛ:ɾɨ bɪn̪d̪iː] |

ḷa [ɭ] |

The letter ਸ਼, already in use by the time of the earliest Punjabi grammars produced, along with ਜ਼ and ਲ਼,[49] enabled the previously unmarked distinction of /s/ and the well-established phoneme /ʃ/, which is used even in native echo doublets e.g. rō̆ṭṭī-śō̆ṭṭī "stuff to eat"; the loansounds f, z, x, and ġ as distinct phonemes are less well-established,[50] decreasing in that order and often dependent on exposure to Hindi-Urdu norms.[42]

The character ਲ਼ (ḷa), the only character not representing a fricative consonant, was only recently officially added to the Gurmukhī alphabet.[51] It was not a part of the traditional orthography, as the distinctive phonological difference between /lə/ and /ɭə/, while both native sounds,[27] was not reflected in the script,[25] and its inclusion is still not currently universal.[note 5] Previous usage of another glyph to represent this sound, [ਲ੍ਰ], has also been attested.[45] The letters ਲ਼ ḷa, like ਙ ṅ, ਙ ṅ, ਣ ṇ, and ੜ ṛ, do not occur word-initially, except in some cases their names.[43]

Other characters, like the more recent [ਕ਼] /qə/,[51] are also on rare occasion used unofficially, chiefly for transliterating old writings in Persian and Urdu, the knowledge of which is less relevant in modern times.[note 6]

Subscript letters

Three "subscript" letters, called duttă akkhară ("joint letters") or pairī̃ akkhară ("letters at the feet") are utilised in modern Gurmukhī: forms of ਹ ha, ਰ ra, and ਵ va.[22]

The subscript ਰ ra and ਵ va are used to make consonant clusters and behave similarly; subjoined ਹ ha introduces tone.

| Subscript letter | Name, original form | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| ੍ਰ | pairī̃ rārā ਰ→ ੍ਰ |

For example, the letter ਪ (pa) with a regular ਰ (ra) following it would yield the word ਪਰ /pəɾə̆/ ("but"), but with a subjoined ਰ would appear as ਪ੍ਰ- (/prə-/),[6] resulting in a consonant cluster, as in the word ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧਕ (/pɾəbə́n̪d̪əkə̆/, "managerial, administrative"), as opposed to ਪਰਬੰਧਕ /pəɾᵊbə́n̪d̪əkə̆/, the Punjabi form of the word used in natural speech in less formal settings (the Punjabi reflex for Sanskrit /pɾə-/ is /pəɾ-/) . This subscript letter is commonly used in Punjabi[46] for personal names, some native dialectal words,[53] loanwords from other languages like English and Sanskrit, etc. |

| ੍ਵ | pairī̃ vāvā ਵ→ ੍ਵ |

Used occasionally in Gurbani (Sikh religious scriptures) but rare in modern usage, it is largely confined to creating the cluster /sʋə-/[46] in words borrowed from Sanskrit, the reflex of which in Punjabi is /sʊ-/, e.g. Sanskrit ਸ੍ਵਪ੍ਨ /s̪ʋɐ́p.n̪ɐ/→Punjabi ਸੁਪਨਾ /sʊpə̆na:/, "dream", cf. Hindi-Urdu /səpna:/.

For example, ਸ with a subscript ਵ would produce ਸ੍ਵ (sʋə-) as in the Sanskrit word ਸ੍ਵਰਗ (/sʋəɾᵊgə/, "heaven"), but followed by a regular ਵ would yield ਸਵ- (səʋ-) as in the common word ਸਵਰਗ (/səʋəɾᵊgə̆/, "heaven"), borrowed earlier from Sanskrit but subsequently changed. The natural Punjabi reflex, ਸੁਰਗ /sʊɾᵊgə̆/, is also used in everyday speech. |

| ੍ਹ | pairī̃ hāhā ਹ→ ੍ਹ |

The most common subscript,[46] this character does not create consonant clusters, but serves as part of Punjabi's characteristic tone system, indicating a tone. It behaves the same way in its use as the regular ਹ (ha) does in non-word-initial positions. The regular ਹ is pronounced in stressed positions (as in ਆਹੋ āhō "yes" and a few other common words),[54] word-initially in monosyllabic words, and usually in other word-initial positions,[note 7] but not in other positions, where it instead changes the tone of the applicable adjacent vowel.[6][57] The difference in usage is that the regular ਹ is used after vowels, and the subscript version is used when there is no vowel, and is attached to consonants.

For example, the regular ਹ is used after vowels as in ਮੀਂਹ (transcribed as mĩh (IPA: [míː]), "rain").[6] The subjoined ਹ (ha) acts the same way but instead is used under consonants: ਚ (ca) followed by ੜ (ṛa) yields ਚੜ (caṛă), but not until the rising tone is introduced via a subscript ਹ (ha) does it properly spell the word ਚੜ੍ਹ (cáṛĭ, "climb"). This character's function is similar to that of the udātă character (ੑ U+0A51), which occurs in older texts and indicates a rising tone. |

In addition to the three standard subscript letters, another subscript character representing the subjoined /j/, the yakaśă or pairī̃ yayyā ( ੵ U+0A75), is utilized specifically in archaized sahaskritī-style writings in Sikh scripture, where it is found 268 times[58] for word forms and inflections from older phases of Indo-Aryan,[59] as in the examples ਰਖੵਾ /ɾəkʰːjaː/ "(to be) protected", ਮਿਥੵੰਤ /mɪt̪ʰjən̪t̪ə/ "deceiving", ਸੰਸਾਰਸੵ /sənsaːɾəsjə/ "of the world", ਭਿਖੵਾ /pɪ̀kʰːjaː/ "(act of) begging", etc. There is also a conjunct form of the letter yayyā, ਯ→੍ਯ,[6] a later form,[60] which functions similarly to the yakaśă, and is used exclusively for Sanskrit borrowings, and even then rarely. In addition, miniaturized versions of the letters ਚ, ਟ, ਤ, and ਨ are also found in limited use as subscript letters in Sikh scripture.

Only the subjoined /ɾə/ and /hə/ are commonly used;[19] usage of the subjoined /ʋə/ and conjoined forms of /jə/, already rare, is increasingly scarce in modern contexts.

Vowel diacritics

| Vowel | Transcription | IPA | Closest English equivalent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ind. | Dep. | with /k/ | Name | Usage | ||

| ਅ | (none) | ਕ | mukḁ̆tā ਮੁਕਤਾ |

a | [ə] | like a in about |

| ਆ | ਾ | ਕਾ | kannā ਕੰਨਾ |

ā | [aː]~[äː] | like a in car |

| ਇ | ਿ | ਕਿ | siā̀rī ਸਿਹਾਰੀ |

i | [ɪ] | like i in it |

| ਈ | ੀ | ਕੀ | biā̀rī ਬਿਹਾਰੀ |

ī | [iː] | like i in litre |

| ਉ | ੁ | ਕੁ | auṅkaṛă ਔਂਕੜ |

u | [ʊ] | like u in put |

| ਊ | ੂ | ਕੂ | dulaiṅkaṛă ਦੁਲੈਂਕੜ |

ū | [uː] | like u in spruce |

| ਏ | ੇ | ਕੇ | lā̃/lāvā̃ ਲਾਂ/ਲਾਵਾਂ |

ē | [eː] | like e in Chile |

| ਐ | ੈ | ਕੈ | dulāvā̃ ਦੁਲਾਵਾਂ |

ai | [ɛː]~[əi] | like e in sell |

| ਓ | ੋ | ਕੋ | hōṛā ਹੋੜਾ |

ō | [oː] | like o in more |

| ਔ | ੌ | ਕੌ | kanauṛā ਕਨੌੜਾ |

au | [ɔː]~[əu] | like o in off |

To express vowels (singular, sură), Gurmukhī, as an abugida, makes use of obligatory diacritics called lagā̃.[22] Gurmukhī is similar to Brahmi scripts in that all consonants are followed by an inherent schwa sound. This inherent vowel sound can be changed by using dependent vowel signs which attach to a bearing consonant.[6] In some cases, dependent vowel signs cannot be used – at the beginning of a word or syllable[6] for instance – and so an independent vowel character is used instead.

Independent vowels are constructed using the three vowel-bearing characters:[6] ੳ ūṛā , ਅ aiṛā, and ੲ īṛī.[23] With the exception of aiṛā (which in isolation represents the vowel [ə]), the bearer vowels are never used without additional vowel diacritics.[31]

Vowels are always pronounced after the consonant they are attached to. Thus, siā̀rī is always written to the left, but pronounced after the character on the right.[31] When constructing the independent vowel for [oː], ūṛā takes an irregular form instead of using the usual hōṛā.[22][23]

Orthography

Gurmukhi orthography prefers vowel sequences over the use of semivowels ("y" or "w") intervocally and in syllable nuclei,[61] as in the words ਦਿਸਾਇਆ disāiā "caused to be visible" rather than disāyā, ਦਿਆਰ diāră "cedar" rather than dyāră, and ਸੁਆਦ suādă "taste" rather than swādă,[44] permitting vowels in hiatus.[62]

In terms of tone orthography, the short vowels [ɪ] and [ʊ], when paired with [h] to yield /ɪh/ and /ʊh/, represent [é] and [ó] with high tones respectively, e.g. ਕਿਹੜਾ kihṛā (IPA: [kéːɽaː]) 'which?' ਦੁਹਰਾ duhrā (IPA: [d̪óːɾaː]) "repeat, reiterate, double."[6] The compounding of [əɦ] with [ɪ] or [ʊ] yield [ɛ́ː] and [ɔ́ː] respectively, e.g. ਮਹਿੰਗਾ mahingā (IPA: [mɛ́ːŋgaː]) "expensive", ਵਹੁਟੀ vahuṭṭī (IPA: [wɔ́ʈːiː]) "bride."[6]

Other signs

The diacritics for gemination and nasalization are together referred to as ਲਗਾਖਰ lagākkhară ("applied letters").

Gemination

The diacritic ਅੱਧਕ áddakă ( ੱ ) indicates that the following consonant is geminated,[19][6] and is placed above the consonant preceding the geminated one.[22] Consonant length is distinctive in the Punjabi language and the use of this diacritic can change the meaning of a word, as below:

| Without áddakă | Transliteration | Meaning | With áddakă | Transliteration | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ਦਸ | dasă | ten | ਦੱਸ | dassĭ | tell (verb) |

| ਪਤਾ | patā | aware of/address | ਪੱਤਾ | pattā | leaf |

| ਬੁਝਣਾ | bújăṇā | to burn out, be extinguished | ਬੁੱਝਣਾ | bújjăṇā | to think through, figure out, solve |

| ਕਲਾ | kalā | art | ਕੱਲਾ | kallā | alone (colloquialism) |

It has not been standardized to be written in all instances of gemination;[61] there is a strong tendency, especially in rural dialects, to also geminate consonants following a long vowel (/a:/, /e:/, /i:/, /o:/, /u:/, /ɛ:/, /ɔː/, which triggers shortening in these vowels) in the penult of a word, e.g. ਔਖਾ aukkhā "difficult", ਕੀਤੀ kī̆ttī "did", ਪੋਤਾ pō̆ttā "grandson", ਪੰਜਾਬੀ panjā̆bbī "Punjabi", ਹਾਕ hākă "call, shout", but plural ਹਾਕਾਂ hā̆kkā̃.[note 8] Except in this case, where this unmarked gemination is often etymologically rooted in archaic forms,[63] and has become phonotactically regular,[64] the usage of the áddakă is obligatory.

It is also sometimes used to indicate second-syllable stress, e.g. ਬਚਾੱ ba'cā, "save".[61]

Nasalisation

The diacritics ਟਿੱਪੀ ṭippī ( ੰ ) and ਬਿੰਦੀ bindī ( ਂ ) are used for producing a nasal phoneme depending on the following obstruent or a nasal vowel at the end of a word.[19] All short vowels are nasalized using ṭippī and all long vowels are nasalized using bindī except for dulaiṅkaṛă ( ੂ ), which uses ṭippī instead.

| Diacritic usage | Result | Examples (IPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Ṭippī on short vowel (/ə/, /ɪ/, /ʊ/), or dependent long vowel /u:/, before a non-nasal consonant[6] | Adds nasal consonant at same place of articulation as following consonant (/ns/, /n̪t̪/, /ɳɖ/, /mb/, /ŋg/, /nt͡ʃ/ etc.) |

ਹੰਸ /ɦənsə̆/ "goose" ਅੰਤ /ən̪t̪ə̆/ "end" ਗੰਢ /gə́ɳɖə̆/ "knot" ਅੰਬ /əmbə̆/ "mango" ਸਿੰਗ /sɪŋgə̆/ "horn, antler" ਕੁੰਜੀ / kʊɲd͡ʒiː/ "key" ਗੂੰਜ /guːɲd͡ʒə̆/ "rumble, echo" ਲੂੰਬੜੀ /luːmbᵊɽiː/ "fox" |

| Bindī over long vowel (/a:/, /e:/, /i:/, /o:/, independent /u:/, /ɛ:/, /ɔː/)[6] before a non-nasal consonant not including /h/[45] |

Adds nasal consonant at same place of articulation as following consonant (/ns/, /n̪t̪/, /ɳɖ/, /mb/, /ŋg/, /nt͡ʃ/ etc.). May also secondarily nasalize the vowel |

ਕਾਂਸੀ /kaːnsiː/ "bronze" ਕੇਂਦਰ /keːn̯d̯əɾə̆/ "center, core, headquarters" ਗੁਆਂਢੀ /gʊáːɳɖiː/ "neighbor" ਭੌਂਕ /pɔ̀ːŋkə̆/ "bark, rave" ਸਾਂਝ /sáːɲd͡ʒə̆/ "commonality" |

| Ṭippī over consonants with dependent long vowel /u:/ at open syllable at end of word[6] or ending in /ɦ/[45] |

Vowel nasalization | ਤੂੰ /t̪ũː/ "you" ਸਾਨੂੰ /sanːũː/ "to us" ਮੂੰਹ /mũːɦ/ "mouth" |

| Ṭippī on short vowel before nasal consonant (/n̪/ or /m/)[6] | Gemination of nasal consonant Ṭippī is used to geminate nasal consonants instead of áddakă |

ਇੰਨਾ /ɪn̪:a:/ "this much" ਕੰਮ /kəm:ə̆/ "work" |

| Bindī over long vowel (/a:/, /e:/, /i:/, /o:/, /u:/, /ɛ:/, /ɔː/),[6] at open syllable at end of word, or ending in /ɦ/ |

Vowel nasalization | ਬਾਂਹ /bã́h/ "arm" ਮੈਂ /mɛ̃ː/ "I, me" ਅਸੀਂ /əsĩː/ "we" ਤੋਂ /t̪õː/ "from" ਸਿਊਂ /sɪ.ũː/ "sew" |

Older texts may follow other conventions.

Vowel suppression

The ਹਲੰਤ halantă, or ਹਲੰਦ halandă, ( ੍ U+0A4D) character is not used when writing Punjabi in Gurmukhī. However, it may occasionally be used in Sanskritised text or in dictionaries for extra phonetic information. When it is used, it represents the suppression of the inherent vowel.

The effect of this is shown below:

- ਕ – kə

- ਕ੍ – k

Punctuation

The ḍaṇḍī (।) is used in Gurmukhi to mark the end of a sentence.[31] A doubled ḍaṇḍī, or doḍaṇḍī (॥) marks the end of a verse.[65]

The visarga symbol (ਃ U+0A03) is used very occasionally in Gurmukhī. It can represent an abbreviation, as the period is used in English, though the period for abbreviation, like commas, exclamation points, and other Western punctuation, is freely used in modern Gurmukhī.[65][31]

Numerals

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Gurmukhī has its own set of digits, which function exactly as in other versions of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. These are used extensively in older texts. In modern contexts, they are sometimes replaced by standard Western Arabic numerals.[61]

| Numeral | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Name | ਸੁੰਨ | ਇੱਕ | ਦੋ | ਤਿੰਨ | ਚਾਰ | ਪੰਜ | ਛੇ | ਸੱਤ | ਅੱਠ | ਨੌਂ |

| Transliteration | sunnă | ikkă | dо̄ | tinnă* | cāră | panjă | chē | sattă | aṭṭhă | na͠u |

| IPA | [sʊnːə̆] | [ɪkːə̆] | [d̪oː] | [t̪ɪnːə̆] | [t͡ʃaːɾə̆] | [pənd͡ʒə̆] | [t͡ʃʰeː] | [sət̪ːə̆] | [əʈːʰə̆] | [nɔ̃:] |

*In some Punjabi dialects, the word for three is ਤ੍ਰੈ trai (IPA: [t̪ɾɛː]).[66]

Glyphs

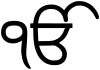

The scriptural symbol for the Sikh term ਇੱਕੁ ਓਅੰਕਾਰੁ ikku о̄aṅkāru (ੴ U+0A74) is formed from ੧ ("1") and ਓ ("о̄").

Palaeography

Spacing

Before the 1970s, Gurbani and other Sikh scriptures were written in the traditional scriptio continua method of writing the Gurmukhi script known as ਲੜੀਵਾਰ laṛīvāră, where there were no spacing between words in the texts (interpuncts in the form of a dot were used by some to differentiate between words, such as by Guru Arjan[citation needed]). This is opposed to the comparatively more recent method of writing in Gurmukhi known as padă chēdă, which breaks the words by inserting spacing between them.[68][69][70]

First line of the Guru Granth Sahib, the Mul Mantar, in laṛīvāră (continuous form) and padă chēdă (spaced form):[71]

laṛīvāră: ੴਸਤਿਨਾਮੁਕਰਤਾਪੁਰਖੁਨਿਰਭਉਨਿਰਵੈਰੁਅਕਾਲਮੂਰਤਿਅਜੂਨੀਸੈਭੰਗੁਰਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ॥

padă chēdă: ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥

Transliteration: ikku ōaṅkāru sati nāmu karatā purakhu nirapàu niravairu akāla mūrati ajūnī saipàṅ gura prasādi

Styles

Various historical styles and fonts, or ਸ਼ੈਲੀ śailī, of Gurmukhi script have evolved and been identified. A list of some of them is as follows:[73]

- purātana ("old") style

- ardha śikastā ("half-broken") style

- śikastā ("broken") style (including Anandpur Lipi)

- Kaśmīrī style

- Damdamī style

Unicode

Gurmukhī script was added to the Unicode Standard in October 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

Many sites still use proprietary fonts that convert Latin ASCII codes to Gurmukhī glyphs.

The Unicode block for Gurmukhī is U+0A00–U+0A7F:

| Gurmukhi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+0A0x | ਁ | ਂ | ਃ | ਅ | ਆ | ਇ | ਈ | ਉ | ਊ | ਏ | ||||||

| U+0A1x | ਐ | ਓ | ਔ | ਕ | ਖ | ਗ | ਘ | ਙ | ਚ | ਛ | ਜ | ਝ | ਞ | ਟ | ||

| U+0A2x | ਠ | ਡ | ਢ | ਣ | ਤ | ਥ | ਦ | ਧ | ਨ | ਪ | ਫ | ਬ | ਭ | ਮ | ਯ | |

| U+0A3x | ਰ | ਲ | ਲ਼ | ਵ | ਸ਼ | ਸ | ਹ | ਼ | ਾ | ਿ | ||||||

| U+0A4x | ੀ | ੁ | ੂ | ੇ | ੈ | ੋ | ੌ | ੍ | ||||||||

| U+0A5x | ੑ | ਖ਼ | ਗ਼ | ਜ਼ | ੜ | ਫ਼ | ||||||||||

| U+0A6x | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | ||||||

| U+0A7x | ੰ | ੱ | ੲ | ੳ | ੴ | ੵ | ੶ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Digitization

Manuscripts

Panjab Digital Library[74] has taken up digitization of all available manuscripts of Gurmukhī Script. The script has been in formal use since the 1500s, and a lot of literature written within this time period is still traceable. Panjab Digital Library has digitized over 45 million pages from different manuscripts and most of them are available online.

Internet domain names

Punjabi University Patiala has developed label generation rules for validating international domain names for internet in Gurmukhi.[75]

See also

Notes

- ^

- The Gurmukhi character ਖ [kha] may have originally evolved from the Brahmi character denoting [ṣa], as the Sanskrit sounds /ʂə/ and /kʰə/ merged into /kʰə/ in Punjabi. Any phonemic contrast was lost, with no distinct character for [ṣa] remaining. Similarly, the characters representing /sə/ and /ʃə/ may have also converged into the character representing /ʃə/ as the sounds merged into /sə/.

- The predecessor of the Gurmukhi character ੜ [ṛa] was derived at a subsequent point, likely around the period of the Laṇḍā scripts, as preceding scripts lacked a character for this sound. It may ultimately share a mutual parent character with Gurmukhi ਡ [ḍa].

- ^ This letter is also commonly referred to as āṛā.

- ^ According to Bhardwaj, "the only commonly used words in which [ਙ and ਞ] occur are ਲੰਙਾ laṅṅā "lame," ਕੰਙਣ kaṅṅaṇă "bracelet," ਵਾਂਙੁ vāṅṅŭ "in the manner of," ਜੰਞ jaññă "wedding party" and ਅੰਞਾਣਾ aññāṇā, "ignorant" or "child.""[43] Besides these archaic spellings, others words include the folk word ਤ੍ਰਿੰਞਣ triññaṇă "a women's gathering," and the early modern loanword ਇੰਞਣ iññaṇă "engine, train".

- ^ The sounds [f]~[ɸ] and [ʃ] can natively occur as allophones of [pʰ] and [t͡ʃʰ] respectively.

- ^ Masica notes that ungeminated /l/ in non-initial positions tends to undergo retroflexion as a general rule regardless in Northwestern Indo-Aryan,[52] and the distinction in writing is "commonly ignored";[25] according to Bhardwaj, [ɭ] is not universally phonemic, and "most of those who use it are not in favour of a having a separate letter ਲ਼ for this sound."[27]

- ^ According to Bhardwaj, "the use of [ਲ਼ and ਕ਼] (especially ਕ਼) is regarded as unnecessarily pedantic by most writers."[27] Shackle notes [q] as "absent from the Panjabi phonemic inventory."[50]

- ^ Word-initial /h/ in unstressed positions may also often be elided and yield a falling tone; for example, in the words ਹਿਸਾਬ hisābă /hɪsaːbə̆/ ("account, estimate") and ਸਾਹਿਬ sāhibă /saːhɪbə̆/ (an honorific, "sir, lord", etc.). Unstressed short vowels may be reduced[55][56] to yield h(a)sābă /həsaːbə̆/ and sāh(a)bă /saːhəbə̆/, and further h-elision in unstressed initial positions may yield near-homophones only distinguished by tone: ਸ੍ਹਾਬ sā̀bă /sàːbə̆/ and ਸਾਬ੍ਹ sā́bă /sáːbə̆/ respectively. Word-initial /h/ may also produce a tone without being elided.[56]

- ^ This does not include consonants which are not naturally geminated, i.e. ਹ ha, ਣ ṇa, ਰ ra, ਵ va, ੜ ṛa, and the navīnă ṭollī consonants.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Bāhrī 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 143.

- ^ Mandair, Arvind-Pal S.; Shackle, Christopher; Singh, Gurharpal (December 16, 2013). Sikh Religion, Culture and Ethnicity. Routledge. p. 13, Quote: "creation of a pothi in distinct Sikh script (Gurmukhi) seem to relate to the immediate religio–political context ...". ISBN 9781136846342. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Mann, Gurinder Singh; Numrich, Paul; Williams, Raymond (2007). Buddhists, Hindus, and Sikhs in America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 100, Quote: "He modified the existing writing systems of his time to create Gurmukhi, the script of the Sikhs; then ...". ISBN 9780198044246. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Shani, Giorgio (March 2002). "The Territorialization of Identity: Sikh Nationalism in the Diaspora". Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism. 2: 11. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9469.2002.tb00014.x.

...the Guru Granth Sahib, written in a script particular to the Sikhs (Gurmukhi)...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Harjeet Singh Gill (1996). "The Gurmukhi Script". In Peter T. Daniels; William Bright (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 395–399. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^ a b c Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Harnik Deol, Religion and Nationalism in India. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-20108-X, 9780415201087. Page 22. "(...) the compositions in the Sikh holy book, Adi Granth, are a melange of various dialects, often coalesced under the generic title of Sant Bhasha."

The making of Sikh scripture by Gurinder Singh Mann. Published by Oxford University Press US, 2001. ISBN 0-19-513024-3, ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9 Page 5. "The language of the hymns recorded in the Adi Granth has been called Sant Bhasha, a kind of lingua franca used by the medieval saint-poets of northern India. But the broad range of contributors to the text produced a complex mix of regional dialects."

Surindar Singh Kohli, History of Punjabi Literature. Page 48. National Book, 1993. ISBN 81-7116-141-3, ISBN 978-81-7116-141-6. "When we go through the hymns and compositions of the Guru written in Sant Bhasha (saint-language), it appears that some Indian saint of 16th century..."

Nirmal Dass, Songs of the Saints from the Adi Granth. SUNY Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7914-4683-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-4683-6. Page 13. "Any attempt at translating songs from the Adi Granth certainly involves working not with one language, but several, along with dialectical differences. The languages used by the saints range from Sanskrit; regional Prakrits; western, eastern and southern Apabhramsa; and Sahiskriti. More particularly, we find sant bhasha, Marathi, Old Hindi, central and Lehndi Panjabi, Sgettland Persian. There are also many dialects deployed, such as Purbi Marwari, Bangru, Dakhni, Malwai, and Awadhi." - ^ a b c "Let's Learn Punjabi: Research Centre for Punjabi Language Technology, Punjabi University, Patiala". learnpunjabi.org. Punjabi University, Patiala. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Arun; Kaur, Amandeep (2018). A New Approach to Punjabi Text Steganography using Naveen Toli. Department of Computer Science & Technology, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, India. ISBN 978-8-193-38970-6.

- ^ Salomon 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Salomon 2007, p. 94-99, 72-73.

- ^ a b Salomon 2007, p. 68-69.

- ^ a b c d e f Salomon 2007, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e Shackle 2007, p. 594.

- ^ a b c d e Salomon 2007, p. 84.

- ^ Bühler, Georg (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. Strassburg K.J. Trübner. pp. 53–77.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d Masica 1993, p. 149.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 145.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 470.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bāhrī 2011, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Grierson 1916, p. 626.

- ^ a b c Masica 1993, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Masica 1993, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pandey, Anshuman (2009-03-25). "N3545: Proposal to Encode the Sharada Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- ^ a b c d Bhardwaj 2016, p. 48.

- ^ a b Grierson 1916, pp. 638–639.

- ^ Pandey, Anshuman (2015-11-04). "L2/15-234R: Proposal to encode the Dogra script" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- ^ Pandey, Anshuman (2009-01-29). "N4159: Proposal to Encode the Multani Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-26. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Bāhrī 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Grierson 1916, pp. 624, 628.

- ^ Bhardwaj 2016, p. 18.

- ^ Deol, Harnik (2003). Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab (illustrated ed.). Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 9781134635351. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Munish; Jindal, M.K.; Sharma, R.K. (2011). Nagamalai, Dhinaharan; Renault, Eric; Dhanuskodi, Murugan (eds.). Advances in Digital Image Processing and Information Technology: First International Conference on Digital Image Processing and Pattern Recognition, DPPR 2011, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India, September 23-25, 2011, Proceedings. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 274. ISBN 9783642240553.

- ^ Bhardwaj 2016, p. 14.

- ^ a b Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 978-0-415-26604-8.

- ^ Bashir, Elena; Conners, Thomas J. (2019). A Descriptive Grammar of Hindko, Panjabi, and Saraiki (Volume 4 of Mouton-CASL Grammar Series). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. p. 18. ISBN 9781614512257. Archived from the original on 2020-06-30. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ Bhardwaj 2016, p. 13.

- ^ a b Salomon 2007, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Bhardwaj 2016, p. 16.

- ^ a b Shackle 2007, p. 589.

- ^ a b Bhardwaj 2016, p. 42.

- ^ a b Masica 1993, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Grierson 1916, p. 627.

- ^ a b c d Shackle 2007, p. 596.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 118.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 205.

- ^ Newton, John (1851). A Grammar of the Panjabi Language; With Appendices (2nd ed.). Ludhiana: American Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ a b Shackle 2007, p. 595.

- ^ a b Bhardwaj 2016, p. 382.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 193.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 201.

- ^ Shackle 2007, p. 590.

- ^ Shackle 2007, p. 587.

- ^ a b Bashir, Elena; Conners, Thomas J. (2019). A Descriptive Grammar of Hindko, Panjabi, and Saraiki (Volume 4 of Mouton-CASL Grammar Series). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. pp. 72–74. ISBN 9781614512257. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- ^ Grierson 1916, p. 628.

- ^ Sidhu, Sukhjinder (2006-01-27). "N3073: Proposal to Encode Gurmukhi Sign Yakash" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-22. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- ^ Shackle, Christopher (1973). "The Sahaskritī Poetic Idiom in the Ādi Granth". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 41 (2): 297–313. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00124498. JSTOR 615936. S2CID 190033610.

- ^ Bhardwaj 2016, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Shackle 2007, p. 597.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 190.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 198.

- ^ Shackle 2007, p. 591.

- ^ a b Holloway, Stephanie (19 July 2016). "ScriptSource - Gurmukhi". ScriptSource. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Bhatia, Tej (1993). Punjabi: A cognitive-descriptive grammar. Routledge. p. 367. ISBN 9780415003209. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- ^ David Rose, Gill Rose (2003). Sacred Texts photopack. Folens Limited. p. 12. ISBN 1-84303-443-3.

- ^ Singh, Jasjit (2014). "The Guru's Way: Exploring Diversity Among British Khalsa Sikhs" (PDF). Religion Compass. 8 (7). School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science, University of Leeds: 209–219. doi:10.1111/rec3.12111 – via White Rose.

...until the early 1970s all copies of the Guru Granth Sahib were presented in larivaar format, in which all the words were connected without breaks, after which point the SGPC released a single-volume edition in which the words were separated from one another in 'pad chhed' format (Mann 2001: 126). Whereas previously readers would have to recognize the words and make the appropriate breaks while reading, pad chhed allowed "reading for those who were not trained to read the continuous text." (Mann 2001: 126). The AKJ promotes a return to the larivaar format of the Guru Granth Sahib.

- ^ "IMPORTANCE OF LAREEVAAR". Nihung Santhia. 2018-11-03. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ "Larivaar Gurbani | Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ "Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji -: Ang : 1 -: ਸ਼੍ਰੀ ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ ਜੀ :- SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ Singh, Gurbaksh (1949–1950). Gurmukhi Lipi Da Janam Te Vikas (in Punjabi). Punjab University Chandigarh. p. 167.

- ^ "Styles of Gurumukhi script". Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- ^ "Panjab Digital Library". Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- ^ "Now, domain names in Gurmukhi". The Tribune. 2020-03-04. Archived from the original on 2020-10-03. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

Bibliography

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Salomon, Richard (2007). "Writing Systems of the Indo-Aryan Languages". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 68–114. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Shackle, Christopher (2007). "Panjabi". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 582–622. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9..

- Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Bāhrī, Hardev (2011). "Gurmukhī". In Siṅgh, Harbans (ed.). Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Vol. I (A–D) (3th ed.). Patiala: Punjab University. pp. 181–184. ISBN 9788173801006.

- Grierson, George A. (1916). "Pañjābī". Linguistic Survey of India. Vol. IX: Indo-Aryan family. Central group, Part 1, Specimens of Western Hindi and Pañjābī. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India. pp. 624–629.

- Bhardwaj, Mangat Rai (2016). Panjabi: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315760803. ISBN 9781138793859.

The following Punjabi-language publications have been written on the origins of the Gurmukhī script:

- Singh, Gurbaksh (G.B.) (1950). Gurmukhi Lipi da Janam te Vikas (in Punjabi) (5th ed.). Chandigarh, Punjab, India: Punjab University Press, 2010. ISBN 81-85322-44-9. Alternative link

- Ishar Singh Tãgh Gurmukhi Lipi da Vigyamulak Adhiyan. Patiala: Jodh Singh Karamjit Singh.

- Kala Singh Bedi Lipi da Vikas. Patiala: Punjabi University, 1995.

- Dakha, Kartar Singh (1948). Gurmukhi te Hindi da Takra (in Punjabi).

- Padam, Piara Singh (1953). Gurmukhi Lipi da Itihas (PDF) (in Punjabi). Patiala, Punjab, India: Kalgidhar Kalam Foundation Kalam Mandir. Alternative link

- Prem Parkash Singh "Gurmukhi di Utpati." Khoj Patrika, Patiala: Punjabi University.

- Pritam Singh "Gurmukhi Lipi." Khoj Patrika. p. 110, vol.36, 1992. Patiala: Punjabi University.

- Sohan Singh Galautra. Punjab dian Lipiã.

- Tarlochan Singh Bedi Gurmukhi Lipi da Janam te Vikas. Patiala: Punjabi University, 1999.