Italian tree frog

| Italian tree frog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Hylidae |

| Genus: | Hyla |

| Species: | H. intermedia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hyla intermedia Boulenger, 1882

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Hyla italica Nascetii, Lanza & Bullini, 1995 | |

The Italian tree frog (Hyla intermedia) is a species of frog in the family Hylidae, found in Italy, Slovenia, Switzerland, and possibly San Marino. Its natural habitats are temperate forests, rivers, intermittent rivers, freshwater marshes, intermittent freshwater marshes, arable land, and urban areas. It is threatened by habitat loss.

Description

The Italian tree frog is very similar in colouring to the European tree frog of which it was previously believed to be a subspecies.[2] It grows to a length of 4 to 5 centimetres (1.6 to 2.0 in) and females are usually larger than males. The skin on the dorsal surface is smooth and bright green. The ventral surface is whitish and clearly demarcated from the dorsal surface by a beige line. A black stripe extends from the eye to the armpit. The female has a white throat while the male has a golden brown one with an inflatable vocal sac. The hind legs are longer than the forelegs and the digits of the hands and feet end in adhesive discs.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The Italian tree frog is native to continental Italy and Sicily. It is very rare in southern Switzerland and in a small area of western Slovenia close to the Italian border. It is found in lowland woods, forests, mountain valleys and wet habitats such as reed beds, at altitudes of up to 1,855 metres (6,086 ft).[1]

Biology

The Italian tree frog is able to climb bushes and trees and move around the countryside via hedgerows, ditches and canals.[3] It feeds on small invertebrates such as flies, mosquitoes and midges. In the breeding season, dominant males establish territories near a pond, paddy field, or other area of water and advertise themselves by calling.[4] Each call consists of a repeated series of six to ten pulses which start quietly and increase in intensity and which varies in frequency and pulse rate between different males. Females appear to take notice of various attributes of the calls when choosing a male.[4] Other male frogs, known as "satellites" and often rather smaller than the calling males, may lurk nearby and try to intercept females attracted by the territorial males' calls, a form of parasitism.[5]

Status

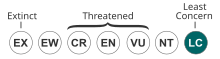

The IUCN has rated the Italian tree frog as being of "Least Concern" in its Red List of Threatened Species. This is because it is quite common in Italy and its population size seems stable. Though it is likely to be threatened by habitat loss and possibly by water pollution, it faces no other particular threats.[1]

References

- ^ a b c IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2021). "Hyla intermedia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T149689922A200194170. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T149689922A200194170.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b Duellman, William E. Grzimek's Animal Encyclopedia. 2nd Ed., Vol. 2. Gale, 2003, p. 235.

- ^ Ficetola, Gentile Francesco; De Bernardi, Fiorenza (2004). "Amphibians in a human-dominated landscape: the community structure is related to habitat features and isolation". Biological Conservation. 119 (2): 219–230. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2003.11.004.

- ^ a b Castellano, Sergio; Rosso, Alessandra (2007). "Female preferences for multiple attributes in the acoustic signals of the Italian treefrog, Hyla intermedia". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 61 (8): 1293–1302. doi:10.1007/s00265-007-0360-z.

- ^ Castellano, Sergio; Marconi, Valentina; Zanollo, Valeria; Berto, Giulia (2009). "Alternative mating tactics in the Italian treefrog, Hyla intermedia". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 63 (8): 1109–1118. doi:10.1007/s00265-009-0756-z.