Pinus pinaster

| Pinus pinaster | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnospermae |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Pinus |

| Subgenus: | P. subg. Pinus |

| Section: | P. sect. Pinus |

| Subsection: | Pinus subsect. Pinaster |

| Species: | P. pinaster

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pinus pinaster | |

| |

| Distribution map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Maritime pine, cluster pine | |

Pinus pinaster, the maritime pine[2][3] or cluster pine,[2] is a pine native to the south Atlantic Europe region and parts of the western Mediterranean. It is a hard, fast growing pine bearing small seeds with large wings.

Description

Pinus pinaster is a medium-size tree, reaching 20–35 metres (66–115 feet) tall with a trunk diameter of up to 1.2 m (4 ft), exceptionally 1.8 m (6 ft).

The bark is orange-red, thick, and deeply fissured at the base of the trunk, somewhat thinner in the upper crown.

The leaves ('needles') are in pairs, very stout (2 millimetres or 1⁄16 inch broad), up to 25 cm (10 in) long,[4] and bluish-green to distinctly yellowish-green. The maritime pine features the longest and most robust needles of all European pine species.[4]

The cones are conic, 10–20 cm (4–8 in) long[4] and 4–6 cm (1+1⁄2–2+1⁄2 in) broad at the base when closed, green at first, ripening glossy red-brown when 24 months old. They open slowly over the next few years, or after being heated by a forest fire, to release the seeds, opening to 8–12 cm (3–4+1⁄2 in) broad.

The seeds are 8–10 mm (5⁄16–3⁄8 in) long, with a 20–25 mm (13⁄16–1 in) wing, and are wind-dispersed.

Similar species

Maritime pine is closely related to Turkish pine, Canary Island pine, and Aleppo pine, which all share many features with it. It is a relatively non-variable species, with constant morphology over the entire range.

Distribution and habitat

Its range is in the western Mediterranean Basin and the southern Atlantic coast of Europe, extending from central Portugal and Northern Spain (especially in Galicia) to southern and Western France, east to western Italy, Croatia and south to northern Tunisia, Algeria and northern Morocco.[5] It favours a Mediterranean climate, which is one that has cool, rainy winters and hot, dry summers.[6]

It generally occurs at low to moderate altitudes, mostly from sea level to 600 m (2,000 ft), but up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in the south of its range in Morocco. The high degree of fragmentation in the current natural distribution is caused by two factors: the discontinuity and altitude of the mountain ranges causing isolation of even close populations, and human activity.[7]

Ecology

Pinus pinaster is a popular topic in ecology because of its problematic growth and spread in South Africa for the past 150 years after being imported into the region at the end of the 17th century (1685–1693).[5] It was found spreading in the Cape Peninsula by 1772. Towards the end of the 18th century (1780), P. pinaster was widely planted, and at the beginning of the 19th century (1825–1830), P. pinaster was planted commercially as a timber resource and for the forestry industry.[5] The pine tree species invades large areas and more specifically fynbos vegetation. Fynbos vegetation is a fire-prone shrubland vegetation that is found in the southern and southwest cape of South Africa. It is found in greater abundance close to watercourses.[6] Dispersal, habitat loss, and fecundity are all factors that affect spread rate. The species favors acidic soils with medium to high-density vegetation,[6] but it can also grow in basic soils and even in sandy and poor soils, where only few commercial species can grow.[7]

Pinus pinaster is a diagnostic species of the vegetation class Pinetea halepensis.[8]

Larvae of the moth Dioryctria sylvestrella feed on this pine. Their boring activity causes large quantities of resin to flow from the wounds which weakens the tree and allows fungi and other pathogens to gain entry.[9]

Invasiveness

Results of invasion

Pinus pinaster is a successful invasive species in South Africa. One of the results of its invasion in South Africa is a decrease in the biodiversity of the native environment.[5] The increase of extinction rates of the native species is correlated with the introduction of these species to South Africa. Invasive species occupy habitats of native species often forcing them to extinction or endangerment. For example, invasive species have the potential to decrease the diversity of native plants by 50–86% in the Cape Peninsula of South Africa.[10] P. pinaster is found in shrubland in South Africa; when compared to other environments, shrublands have the largest decline of species richness when invaded by an invasive species (Z=–1.33, p<0.001).[11] Compared to graminoids; trees, annual herbs, and creepers have a larger effect on decline of species richness (Z=–3.78; p<0.001).[11] Lastly, compared to other countries, South Africa had the largest species richness decline when faced with invasive species.[11] South Africa is not home to many insects and diseases that limit the population of P. pinaster back in its native habitat.[5] Not only is there evidence that alien plant invasions decrease biodiversity, but there is also evidence that the location of P. pinaster increases its negative effect on the species richness.

In addition, depending on the regions P. pinaster invades, P. pinaster has the potential to dramatically alter the quantity of water in the environment. If P. pinaster invades an area covered with grasses and shrubs, the water level of the streams in this area would lower significantly because P. pinaster are evergreen trees that take up considerably more water than grasses and shrubs all year around.[12] They deplete run-off in catchment areas and water flow in rivers. This depletes the resources available for other species in the environment. P. pinaster tends to grow rapidly in riparian zones, which are areas with abundant water where trees and plants grow twice as fast and invade. P. pinaster takes advantage of the water available and consequently reduces the amount of water in the area available for other species.[12] The fynbos catchments on the Western Cape of South Africa are a habitat negatively affected by P. pinaster. Twenty-three years after planting the pines, there was a 55% decrease in streamflow in this area.[5] Similarly, in KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg there was an 82% reduction in streamflow 20 years after introducing P. pinaster to the area. In the Mpumalanga Province, 6 streams completely dried up 12 years after grasslands were replaced with pines. To reinforce that, there is a negative effect from the invasive species P. pinaster, these areas of dense P. pinaster were thinned and the number of trees in the area decreased. As a result, the streamflow in the fynbos catchments of the Western Cape increased by 44%. The streamflow in the Mpumalanga Province increased by 120%.[5] As a result of P. pinaster growth, there is often less understory vegetation for livestock grazing. Once again there was a positive effect when some of the pines were removed and agreeable range grasses were planted. The grazing conditions for the sheep of the area were greatly improved when the P. pinaster plantation was thinned to 300 trees per hectare. The invasion of P. pinaster leads to the decrease of understory vegetation and therefore a decrease in livestock.[13]

It is sporadically naturalizing in Oakland and San Leandro in northern California.

Ecological interactions

Pinus pinaster is particularly successful in regions with fynbos vegetation because it is adapted to high-intensity fires, thus allowing it to outcompete other species that are not as well adapted to high-intensity fires. In areas of fire-prone shrubland, the cones of P. pinaster will release seeds when in a relatively high-temperature environment for germination as a recovery mechanism. This adaptation increases the competitive ability of P. pinaster amongst other species in the fire-prone shrubland.[6] In a 3-year observational study done in Northwestern Spain, P. pinaster showed a naturally high regeneration rate.[14] Observations showed a mean of 25.25 seedlings per square metre within the first year and then slowly decreased the next two years due to intraspecific competition.[14] So not only does P. pinaster compete with other species, they also compete within their own species as well. When the height of P. pinaster increased there was a negative correlation with the number of P. pinaster seedlings, results showed a decrease in P. pinaster seedlings (r=–0.41, p<0.05).[14]

Several other characteristics contribute to their success in the regions they have invaded, including their ability to grow rapidly and to produce small seeds with large wings. Their ability to grow quickly with short juvenile periods allows them to outcompete many native species while their small seeds aids in their dispersal. The small seeds with large wings are beneficial for wind dispersal, which is the key to reaching new areas in regions with fynbos vegetation.[6] Vertebrate seed dispersers are not commonly found in mountain fynbos vegetation; therefore those species that require the aid of vertebrate dispersal would be at a disadvantage in such an environment. For this reason, the small seed, low seed wing loading, and high winds found in mountainous regions all combine to provide a favorable situation for the dispersal of P. pinaster seeds.[6] Without this efficient dispersal strategy, P. pinaster would not have been able to reach and invade areas, such as South Africa, that are suitable for its growth. Its dispersal ability is one of the key factors that have allowed P. pinaster to become such a successful invasive species.[6]

In addition to being an efficient disperser, P. pinaster is known to produce oleoresins, such as oily terpenes or fatty acids, which can inhibit other species within the community from growing.[15] These resins are produced as a defense mechanism against insect predators, such as the large pine weevil. According to an experiment done in Spain, the resin canal density was twice as high in the P. pinaster seedlings attacked by the weevils compared to the unattacked seedlings. Since P. pinaster has the ability to regulate their production of defense mechanisms, it can protect itself from predatory in an energy-efficient manner. The resins make the P. pinaster less vulnerable to damage from insects, but they are only produced in high concentrations when P. pinaster is under attack. In other words, P. pinaster does not waste energy producing resins in safe conditions, so the conserved energy can be used for growth or reproduction. These characteristics enhance the ability of P. pinaster survive and flourish in the areas it invades.[16] Both the traits of P. pinaster and the habitat in South Africa are conducive to the success of P. pinaster in this region of the world.

Options for biological control

Insects and mites that feed on the seeds and cones of P. pinaster can be effective biological control options. An insect or mite that acts as an ideal biological control should have a high reproductive rate and be host-specific, meaning that it preys specifically on P. pinaster. The life cycle of the predator should also match that of its specific host. Two key characteristics the predator should also exhibit are self-limitation and the ability to survive in the presence of a declining prey population.[16] Seed feeding insects are an effective control because they have high reproductive rates and target the seeds without diminishing the positive effect of the plant on the environment. Controlling the spread of P. pinaster seeds in the region is the key to limiting the growth and spread of this species because P. pinaster has the ability to produce a large number of seeds that are capable of dispersing very efficiently.[5] One possible option is Trisetacus, an eriophyid mite. The main advantage to using this mite to control the population of P. Pinaster is its specificity to P. pinaster; it can effectively control the population of P. pinaster by destroying the growing conelets in P. pinaster while limiting its impact to only this species. Another possible option is Pissodes validirostris, a cone-feeding weevil that lays eggs in developing cones. When the larvae hatch, they feed on the growing seed tissue, preventing P. pinaster seeds from forming and dispersing. Although the adults feed on the trees as well, they do not do any damage to the seeds and only feed on the shoots of the tree, so they do not appear to negatively impact the growth of the trees. Different forms of P. validirostris have diverged to become host-specific to different pine trees. The type of P. validirostris that originated from Portugal appears to have specialized to P. pinaster; therefore, this insect may be used in the future to control the spread of P. pinaster in South Africa.[17] The uncertainties regarding the host-specificity of different types of P. validirostris, however, require more research to be completed before the introduction of the weevils into South Africa. An introduction of a species that is not host-specific to P. pinaster can lead to detrimental effects on both the environment and industries that are dependent on certain tree species. Two other biological control possibilities include the pyralid moth species Dioryctria mendasella and D. mitatella, but these species attack the vegetative tissue instead of just the seeds of P. pinaster, harming the plant itself.[5] As of now, the eriophyid mite and cone-feeding weevil seem to hold the most potential to controlling the spread of P. pinaster in the regions it has invaded because they destroy the reproductive structures of the target invasive species.

Uses

Pinus pinaster is widely planted for timber in its native area, being one of the most important trees in forestry in France, Spain and Portugal. Landes forest in southwest France is the largest man-made maritime pine forest in Europe. It has also been cultivated in Australia as plantation tree, to provide softwood timber.[18] P. pinaster resin is a useful source of turpentine and rosin.[19]

In addition to industrial uses, maritime pine is also a popular ornamental tree, often planted in parks and gardens in areas with warm temperate climates. It has become naturalised in parts of southern England, Uruguay, Argentina, South Africa and Australia.[20]

It is also used as a source of flavonoids, catechins, proanthocyanidins, and phenolic acids. A dietary supplement derived from extracts from P. pinaster bark called Pycnogenol is marketed with claims it can treat many conditions; however, according to a 2012 Cochrane review, the evidence is insufficient to support its use for the treatment of any chronic disorder.[21]

Pests

Pestalotiopsis pini (a species of ascomycete fungi), was found as an emerging pathogen on Pinus pinea L. (Stone pine) and also on Pinus pinaster in Portugal. Evidence of shoot blight and stem necrosis were found in 2020. The fungus was found on needles, shoots and trunks of the pines.[22]

References

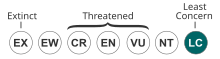

- ^ Farjon, A. (2013). "Pinus pinaster". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42390A2977079. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42390A2977079.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Pinus pinaster Aiton". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Maritime Pine | the Wood Database - Lumber Identification (Softwood)".

- ^ a b c Rushforth, Keith (1986) [1980]. Bäume [Pocket Guide to Trees] (in German) (2nd ed.). Bern: Hallwag AG. p. 63. ISBN 3-444-70130-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Moran et al. (2000).

- ^ a b c d e f g Richardson, M (1990). Assessing the risk of invasive success in Pinus and Banksia in South African mountain fynbos [Journal of Vegetation Science] (1st ed.). pp. 629–642.

- ^ a b Alía, R. & Martín, S. (2003), Maritime pine – Pinus pinaster: Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use (PDF), European Forest Genetic Resources Programme, p. 6 pp, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-19, retrieved 2017-01-18

- ^ Bonari, Gianmaria; Fernández‐González, Federico; Çoban, Süleyman; Monteiro‐Henriques, Tiago; Bergmeier, Erwin; Didukh, Yakiv P.; Xystrakis, Fotios; Angiolini, Claudia; Chytrý, Kryštof; Acosta, Alicia T.R.; Agrillo, Emiliano (January 2021). Ewald, Jörg (ed.). "Classification of the Mediterranean lowland to submontane pine forest vegetation". Applied Vegetation Science. 24 (1). doi:10.1111/avsc.12544. hdl:10400.5/21923. ISSN 1402-2001. S2CID 228839165.

- ^ Ciesla, William (2011). Forest Entomology: A Global Perspective. John Wiley & Sons. p. 546. ISBN 978-1-4443-9788-8.

- ^ Higgins, S (1999). Predicting the Landscape-Scale Distribution of Alien Plants and Their Threat to Plant Diversity [Conservation Biology]. pp. 303–313.

- ^ a b c Gaertner, M (2009). Impacts of alien plant invasions on species richness in Mediterranean-type ecosystems: a meta-analysis [Progress in Physical Geography] (33rd ed.). pp. 319–338.

- ^ a b Carbon, B.A. (1982). "Deep drainage and water use of forests and pastures grown on deep sands in a Mediterranean environment" [Journal of Hydrology]. Journal of Hydrology. 55 (1): 53–63. Bibcode:1982JHyd...55...53C. doi:10.1016/0022-1694(82)90120-2.

- ^ Papanastasis, V. (1995). Effects of thinning, fertilisation and sheep grazing on the understory vegetarion of Pinus pinaster plantations [School of Forestry and Natural Environment]. pp. 181–189.

- ^ a b c Calvo, L (2008). Post-fire natural regeneration of a Pinus pinaster forest in NW Spain [Plant Ecology]. Vol. 197. pp. 81–90.

- ^ Calvo, L (2003). Regeneration after wildfire in communities dominated by Pinus pinaster, an obligate seeder, and in others dominated by Quercus pyrenaica, typical resprouter [Forest Ecology and Management]. Vol. 184. pp. 209–223.

- ^ a b Krebs, C (2009). Ecology [Pearson].

- ^ Hoffmann, J (2011). Prospects for the biological control of invasive Pinus species (Pinaceae) in South Africa [African Entomology]. pp. 393–401.

- ^ "Anglesea Plantation". The Geelong Advertiser. 1926-05-01. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "Interview: Pinus pinaster resin industry in Portugal (portuguese)". AGROTEC. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Pinus pinaster". Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Schoonees, A; Visser, J; Musekiwa, A; Volmink, J (2012). "Pycnogenol (extract of French maritime pine bark) for the treatment of chronic disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008294. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008294.pub4. PMID 22513958.

- ^ Silva, Ana Cristina; Diogo, Eugénio; Henriques, Joana; Ramos, Ana Paula; Sandoval-Denis, Marcelo; Crous, Pedro W.; Bragança, Helena (2020). "Pestalotiopsis pini sp. nov., an Emerging Pathogen on Stone Pine (Pinus pinea L.)". Forests. 11 (8): 805. doi:10.3390/f11080805. hdl:10400.5/20420.

Sources

- Moran, V.C.; Hoffmann, J.H.; Donnelly, D.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Zimmermann, H.G. (2000). "Biological Control of Alien, Invasive Pine Trees (Pinus species) in South Africa" (PDF). Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds: 941–953.

Further reading

- Pinus pinaster – distribution map, genetic conservation units and related resources. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)

- "Pinus pinaster". Plants for a Future.

- Pinus pinaster in the CalPhotos photo database, University of California, Berkeley