Snowy sheathbill

| Snowy sheathbill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Chionidae |

| Genus: | Chionis |

| Species: | C. albus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chionis albus (Gmelin, JF, 1789)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Vaginalis alba Gmelin, 1789 | |

The snowy sheathbill (Chionis albus), also known as the greater sheathbill, pale-faced sheathbill, and paddy, is one of two species of sheathbill. It is usually found on the ground. It is the only land bird native to the Antarctic continent.[3]

Taxonomy

The snowy sheathbill was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it in a new genus Vaginalis and coined the binomial name Vaginalis alba.[4] Gmelin based his description on the "white sheath-bill" that had been described and illustrated in 1785 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his A General Synopsis of Birds .[5] Latham erroneously believed that the bird was found in New Zealand. The type locality was designated as the Falkland Islands by Baron Bradford and Charles Chubb in 1912.[6][7] The snowy sheathbill is now placed in the genus Chionis that was introduced in 1788 by the German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster.[8][9] The genus name is from the Ancient Greek khiōn meaning snow. The specific epithet albus is Latin meaning "white".[10] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[9]

Description

A snowy sheathbill is about 380–410 mm (15–16 in) long, with a wingspan of 760–800 mm (30–31 in). It is pure white except for its pink, warty face; its Latin name translates to "snow white".[11]

Sheathbills spend 86% of their day hunting for food and the other 14% resting.[12]

Distribution and habitat

The snowy sheathbill lives in Antarctica, the Scotia Arc, the South Orkneys, and South Georgia. Snowy sheathbills living very far south migrate north in winter.[3]

Feeding

The snowy sheathbill does not have webbed feet. It finds its food on land. It is an omnivore, a scavenger, and a kleptoparasite and will eat nearly anything. It steals regurgitated krill and fish from penguins when feeding their chicks and will eat their eggs and chicks if given the opportunity. Sheathbills also eat carrion, animal feces, and, where available, human waste. It has been known to eat tapeworms that have been living in a chinstrap penguin's intestine.[11]

Sheathbills that are actively hunting for food spend approximately 38% of the day hunting, 20% of the time eating their prey, 23% just resting, 14% doing various comfortable activities, and the final 3% will be towards agonistic behavior.[12]

Gallery

-

Flying sheathbill

-

This snowy sheathbill is watched carefully by a chinstrap penguin, as they are predators of penguin chicks and eggs

-

Eating regurgitated penguin chick food

-

Snowy sheathbill walks by an Antarctic fur seal, at Cooper Bay, South Georgia

-

Adult snowy sheathbill, on Barrientos Island

References

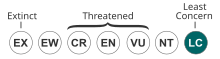

- ^ BirdLife International (2017). "Chionis albus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22693556A118854999. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22693556A118854999.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ The Internet Bird Collection. "Pale-faced Sheathbill (Chionis alba)".

- ^ a b Briggs, Mike; Briggs, Peggy (2004). The Encyclopedia of World Wildlife. Parragon Publishing. ISBN 1-4054-3679-4.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 705.

- ^ Latham, John (1785). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 3, Part 1. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. pp. 268–269, Plate 89.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 308.

- ^ Brabourne, W.; Chubb, C. (1912). The Birds of South America. London: R.H. Porter. p. 36.

- ^ Forster, Johann Reinhold (1788). Enchiridion historiae naturali inserviens, quo termini et delineationes ad avium, piscium, insectorum et plantarum adumbrationes intelligendas et concinnandas, secundum methodum systematis Linnaeani continentur (in Latin). Halae: Prostat apud Hemmerde et Schwetschke. p. 37.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Buttonquail, thick-knees, sheathbills, plovers, oystercatchers, stilts, painted-snipes, jacanas, Plains-wanderer, seedsnipes". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 101, 40. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b Lynch, Wayne (September 26, 2001). The Scoop on Poop. Fifth House Books. ISBN 1-894004-59-0.

- ^ a b Favero, Marco (1996). "Foraging Ecology of Pale-Faced Sheathbills in Colonies of Southern Elephant Seals at King George Island, Antarctica (La Ecología de la Alimentación de la Chionis alba en los Harenes de Elefantes Marinos en la Isla King George, Antarctica)". Journal of Field Ornithology. 67 (2): 292–299. JSTOR 4514110.