Tacca leontopetaloides

| Polynesian arrowroot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Dioscoreales |

| Family: | Dioscoreaceae |

| Genus: | Tacca |

| Species: | T. leontopetaloides

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tacca leontopetaloides | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Tacca leontopetaloides is a species of flowering plant in the yam family Dioscoreaceae. It is native to the islands of Southeast Asia. Austronesian peoples introduced it as a canoe plant throughout the Indo-Pacific tropics during prehistoric times. It has become naturalized to tropical Africa, South Asia, northern Australia, and Oceania.[2] Common names include Polynesian arrowroot, Fiji arrowroot, East Indies arrowroot, pia,[4] and seashore bat lily.[5]

History of cultivation

Polynesian arrowroot is an ancient Austronesian root crop closely related to yams. It is originally native to Island Southeast Asia. It was introduced throughout the entire range of the Austronesian expansion during prehistoric times (c. 5,000 BP), including Micronesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. Polynesian arrowroot have been identified as among the cultivated crops in Lapita sites in Palau, dating back to 3,000 to 2,000 BP.[6] It was also introduced to Sri Lanka, southern India, and possibly also Australia through trade and contact.[7]

Polynesian arrowroot was a minor staple among Austronesians. The roots are bitter if not prepared properly, thus it was only cultivated as a secondary crop to staples like Dioscorea alata and Colocasia esculenta. Its importance increased for settlers in the Pacific Islands, where food plants were scarcer, and it was introduced to virtually all the inhabited islands. They were valued for their ability to grow in low islands and atolls, and were often the staple crops in islands with these conditions. In larger islands, they were usually allowed to grow wild and were useful only as famine food. Several cultivars have been developed in Polynesia due to the centuries of artificial selection. The starch extracted from the root with traditional methods can last for a very long time, and thus can be stored or traded.[6] The starch can be cooked in leaves to make starchy puddings, similar to the use of starch extracted from sago palms (Metroxylon sagu).[8] Due to the introduction of modern crops, it is rarely cultivated today.[6]

Description

The tubers are round, hard and potato-like, with a brown skin and white interior.[4][5] In December, the plant is dormant, the leaves and stalks dry up and die down to the ground until March when new leaves grow back.[9]: 387

The leaves are "palmately incised and/or divided into 3-13 lobes, each lobe pinnately divided into numerous smaller ones".[9]: 401 Several petioles 17–150 cm (6.7–59.1 in) in length extend from the center of the plant which look like giant celery, on which the large leaves (30–70 cm or 12–28 in long and up to 120 cm or 47 in wide) are attached.[5] The leaf's upper surface has depressed veins, and the under surface is shiny with bold yellow veins.

Umbels

Flowers are borne on tall stalks in greenish-purple umbel-like clusters surrounded by large bracts with long whisker-like appendages, their function is unknown. Each single flower has long, threadlike bracteoles 1 cm long.[4][5]

The fruit emerges from the bracts, each fruit are globular 4–5 cm long.[4][5] The fruits ripen and turn from pale or dark green to pale orange. Each fruit produces many flat, ribbed and yellowish brown seeds 5–8 mm long.[9]: 378

-

Inflorescence (umbel)

-

Flower with 6 tepals, 6 stamens and 3-lobed stigma

-

Infructescence

Uses

The tubers of Polynesian arrowroot contain starch, making it an important food source for many Pacific Island cultures, primarily for the inhabitants of low islands and atolls. Polynesian arrowroot was prepared into a flour to make a variety of puddings. The tubers are first grated and then allowed to soak in fresh water. The settled starch is rinsed repeatedly to remove the bitter taste from taccalin, a kind of poisonous substance, and then dried.[9]: 387 The flour was mixed with mashed taro, breadfruit, or pandan fruit extract and mixed with coconut cream to prepare puddings. In Hawaii, a local favorite is haupia, which was originally made with pia flour, coconut cream and kō (cane sugar).[10] Today, Polynesian arrowroot has been largely replaced by cornstarch.

The starch was additionally used to stiffen fabrics, and on some islands, the stem's bast fibres were woven into mats.

In traditional Hawaiian medicine the raw tubers were eaten to treat stomach ailments. Mixed with water and red clay, the plant was consumed to treat diarrhea and dysentery. This combination was also used to stop internal hemorrhaging in the stomach and colon and applied to wounds to stop bleeding.[4]

See also

Notes

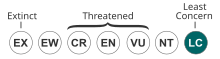

- ^ Contu, S. (2013). "Tacca leontopetaloides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T44392847A44503085. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Tacca leontopetaloides". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Tacca leontopetaloides (L.) Kuntze". World Flora Online. World Flora Consortium. 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Tacca leontopetaloides (Dioscoreaceae)". Meet the Plants. National Tropical Botanical Garden. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Tan, Ria (13 January 2022). "Seashore bat lily (Tacca leontopetaloides)". Wild Singapore. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Farley, Gina; Schneider, Larissa; Clark, Geoffrey; Haberle, Simon G. (December 2018). "A Late Holocene palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of Ulong Island, Palau, from starch grain, charcoal, and geochemistry analyses". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 22: 248–256. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.09.024. hdl:1885/159550.

- ^ Spennemann, Dirk H.R. (1994). "Traditional Arrowroot Production and Utilization in the Marshall Islands". Journal of Ethnobiology. 14 (2): 211–234.

- ^ Thaman, R.R. (1994). "Ethnobotany of the Pacific Island Coastal Plains". In Morrison, John; Geraghty, Paul; Crowl, Linda (eds.). Fauna, Flora, Food and Medicine: Science of Pacific Island Peoples. Vol. 3. Institute of Pacific Studies. pp. 147–184. ISBN 9789820201064.

- ^ a b c d Drenth, E. (1972). "A revision of the family Taccaceae". Blumea. 20 (2): 367–406.

- ^ Brennan 2000, pp. 252–267

References

- Brennan, Jennifer (2000). Tradewinds & Coconuts: A Reminiscence & Recipes from the Pacific Islands. Periplus. ISBN 962-593-819-2..

External links

![]() Media related to Tacca leontopetaloides at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tacca leontopetaloides at Wikimedia Commons