The Dents du Midi (French pronunciation: [dɑ̃ dy midi]; French: "teeth of the south") are a three-kilometre-long mountain range in the Chablais Alps in the canton of Valais, Switzerland. Overlooking the Val d'Illiez and the Rhône valley to the south, they face the Lac de Salanfe, an artificial reservoir, and are part of the geological ensemble of the Giffre massif. Their seven peaks are, from north-east to south-west: the Cime de l'Est, the Forteresse, the Cathédrale, the Éperon, the Dent Jaune, the Doigts and the Haute Cime. They are mainly composed of limestone rock, with gritty limestone rock in the upper parts.

| Dents du Midi | |

|---|---|

The Dents du Midi from Aigle in spring. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,258 m (10,689 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 1,796 m (5,892 ft)[2] |

| Parent peak | Mont Blanc |

| Isolation | 19.0 km (11.8 mi)[3] |

| Listing | Ultra, Alpine mountains above 3000 m |

| Coordinates | 46°09′39.6″N 6°55′24.3″E / 46.161000°N 6.923417°E |

| Geography | |

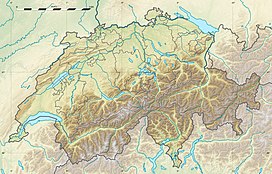

Main peaks in Chablais Alps Mouse over (or touch) gives more detail of peaks. Location in Switzerland | |

| Location | Valais, Switzerland |

| Parent range | Chablais Alps |

| Topo map |  |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | limestone |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1784 |

The Dents du Midi are accessible from Champéry, les Cerniers, Mex, Salvan and Vérossaz, but they have only been climbed since the end of the 18th century. A footpath around the Dents du Midi has existed since 1975. The mountain range represents a local symbol and is often used to promote the Val d'Illiez and various brands and associations in the region.

Names

editThe first name of the Dents du Midi was "Alpe de Chalen" ("alpine pasture of Chalen"), dating from 1342. It was later transformed into Chalin and which gave its name to a glacier, a hamlet and a mountain refuge. The term "dent de Midy" was first mentioned in 1656 in the book Helvetia antiqua et nova by pastor Jean-Baptiste Plantin.[4] During the 19th century several names were used. In writing, the most common were "la dent du Midi" or "la dent de Midi, but the inhabitants of the Val d'Illiez used "dents de Tsallen" or "dents de Zallen", from the Tsalin patois word meaning "high bare pasture".[5][6] The name "Dents du Midi" ("teeth of south") seems to come from the fact that during the 20th century, the inhabitants of the Val d'Illiez used the massif to tell the time. This theory is supported by the old name of the Dent de Bonavau, to the south-east, which was called "Dent-d'une-heure" ("tooth of one o'clock") on maps published in 1928.[7]

The Cime de l'Est (eastern peak) was called "Mont de Novierre" before 1636,[8] then, after a landslide, "Mont Saint-Michel" in honour of the Archangel Michael and finally "dent Noire" ("black tooth") until the first maps. Five of the summits had no names at the time. At the end of the 19th century, the names Forteresse (Fortress), Cathédrale (Cathedral), Éperon (Spur) and Dent Jaune (Yellow Tooth) appeared after the first ascents, although the Éperon and the Dent Jaune still bore the names "Dent Ruinée" (ruined tooth) and "Dent Rouge" (red tooth) on several maps until around 1915. In that year, the "Doigt de Champéry" (Champéry's finger) and the "Doigt de Salanfe" (Salanfe's finger) were grouped together under a common name and became Les Doigts ("the fingers"). The Haute Cime also had several names: "Cime de l'Ouest" (west peak), "Dent du Midi" (tooth of south), "Dent de Tsallen" (tooth of Tsallen) and "Dent de Challent" (tooth of Challent).[5]

Geography

editLocation

editThe Dents du Midi are situated on the border between the communes of Val-d'Illiez and Evionnaz. The north face rises above the Val d'Illiez while the south face overlooks the Lac de Salanfe, an artificial reservoir. The ridge of the chain is situated at an altitude varying between 2,997 and 3,258 meters (9,833 and 10,689 ft); it is visible from Montreux, 30 kilometers (19 mi) to the north, as well as from the whole of the Rhône plain of the Chablais vaudois. The Dents du Midi are oriented along an axis running from north-east to south-east over a length of 3 kilometers (1.9 mi).[9][10]

Topography

editThe main summits of the Dents du Midi are, from north-east to south-west: La Cime de l'Est (3,178 meters; 10,427 ft), La Forteresse (3,164 meters; 10,381 ft), La Cathédrale (3,160 meters; 10,370 ft), L'Éperon (3,114 meters; 10,217 ft), La Dent Jaune (3,186 meters; 10,453 ft), Les Doigts (3,205 and 3,210 meters; 10,515 and 10,531 ft) and La Haute Cime (3,258 meters; 10,689 ft, highest point). The chain is part of the Giffre massif, of which it is the northern limit and which continues south to the Mont Blanc massif.[11]

There are three passes between the different summits: the Cime de l'Est pass (3,032 meters; 9,948 ft), the Fenêtre de Soi (Soi window) between the Forteresse and the La Cathédrale (3,004 meters; 9,856 ft) and the Col des Dents du Midi (Dents du Midi pass) between the Dent Jaune and the Doigts (2,997 meters; 9,833 ft). A fourth, the Col des Paresseux (the lazy ones' pass), is situated below the Haute Cime (3,067 meters; 10,062 ft). The Dents du Midi are linked to the Tour Sallière by a ridge to the south. It is on this ridge that the Col de Susanfe (Susanfe pass) is located, which allows one to pass from the valley of Susanfe to that of Salanfe.[12]

Geology

editThe Dents du Midi appeared about 60 million years ago, during the continental collision between the Africa and Europe. The collision caused folds in the tectonic plate, which caused the Dents du Midi to protrude from the surface. They represent the frontal hinge of the Morcles nappe, which extends to the south-west and includes Mont Joly and the Aravis mountain range in Savoie and Haute-Savoie. When they were formed, the Dents du Midi were connected with the Dent de Morcles. The current shape of the Dents du Midi appeared during the Würm glaciation, the last of the great glaciations, which began 100,000 years ago. It was then that the chain was separated from the Dent de Morcles by the Rhône glacier, that the glacier of the Val d'Illiez cleared the flysch at the base of the Dents du Midi and that the regional waters shaped the summits according to the weaknesses of the rock. According to certain sources, the Éperon was the highest point of the Dents du Midi in the 18th century.[13] The shape of the summit and the presence of boulders towards the Salanfe lake suggest that it collapsed.[13][14]

The summits of the Dents du Midi are formed mainly from limestone rocks formed during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic in the Paleocean Tethys. Among these, we find, on the north face, Urgonian Limestone, formed during the Cretaceous by rudists in a light band at the base of the massif and interspersed with a younger and very dark layer formed by nummulites. Higher up, there is gritty limestone, dating from the Valanginian, which is distinguished by a darker colour. The southern face is made of Cretaceous limestones which cover a sedimentary layer dating from the Triassic.[13] Native flysch appeared during the Alpine folds and covers this layer on the north face. This flysch is formed from clay, elastic quartz and pyrite among other materials.[15][13]

Hydrography

editThere are three glaciers on the chain of the Dents du Midi: the Plan Névé glacier on the south face, and the Chalin and Soi glaciers (also spelled Soy or Soie) on the north face.[16] The latter supplies the Lac de Soi, a small mountain lake located at an altitude of 2,247 meters (7,372 ft). A torrent of the same name starts there and flows into the Vièze.[17] The Lac de Salanfe, which is situated on the southern slope of the Dents du Midi, at an altitude of 1,925 meters (6,316 ft), supplies the Bains de Val-d'Illiez, a thermal park, situated below the northern slope at an altitude of 709 meters (2,326 ft) and 9 kilometers (5.6 mi) from the lake. The hot spring appeared in 1953 after several minor earthquakes. Its origin was unknown until 2001, when a scientific investigation concluded that the water came from a leak to the south of the lake.[18]

Seismicity and landslides

editAccording to the Swiss Seismological Service, the Cime de l'Est and the entire southern face are in seismic risk zone 3b, the category of the most exposed regions, while the northern slope is in seismic risk zone 3a.[19]

There is a large amount of scree on the Dents du Midi. In 1925, the eastern face of the Cime de l'Est collapsed; landslides reached the Bois Noir region in Saint-Maurice over several days, destroying roads and the town's water supply system. Other notable collapses took place in 563, 1635, 1636 and 1835.[20] The last major landslide took place in 2006: 1,000,000 cubic meters (1,300,000 cu yd) of rock broke away from the Haute Cime on the northern slope. These events are high-altitude phenomena and generally do not involve dwellings.[21]

Climate

editAccording to Köppen climate classification, the climate of the Dents du Midi is a tundra climate (ET). There is no weather station on the Dents du Midi. The most representative nearby station is the one on the Rosa Plateau, located 65 kilometers (40 mi) to the south-east at an altitude of 3,440 meters (11,290 ft). The climate in both places has very cold winters and cool summers.[22] The Dents du Midi act as a dam against the air masses coming from the northwest, creating precipitation around the peaks and over the villages of the Val d'Illiez.[23]

| Climate data for Rosa Plateau | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 15.8 (−9.0) |

14 (−10) |

18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

43 (6) |

46 (8) |

46 (8) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

21 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1 (−17) |

0 (−18) |

3 (−16) |

9 (−13) |

19 (−7) |

25 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

30 (−1) |

25 (−4) |

18 (−8) |

9 (−13) |

1 (−17) |

14 (−10) |

| Average precipitation days | 68 | 65 | 64 | 83 | 136 | 118 | 114 | 110 | 93 | 74 | 71 | 73 | 1,069 |

| Source: Meteoblue[22] | |||||||||||||

Fauna and Flora

editThe massif of the Dents du Midi spans an elevation difference of over 2,800 metres, therefore hosting a wide variety of ecosystems, from deciduous forests, to coniferous forests, alpine tundra and glaciers.[24] The highest section of the Dents du Midi is located between the subalpine zone and the snow line, above the tree line. The unstabilised scree slopes at an altitude of around 2,500 meters (8,200 ft) only leave room for particular plant species. For example, the Noccaea rotundifolia, the yellow mountain saxifrage (Saxifraga aizoides) and the purple saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia) or the Artemisia can be found in hard-to-reach places. Rare plants such as Viola cenisia can be found near glaciers. Above 2,500 meters (8,200 ft), the Dents du Midi are covered with snow nine months of the year which means there is very little vegetation. The rare plants that grow here are Bavarian gentians (Gentiana bavarica), snow willow (Salix reticulata) and Ranunculus alpestris.[25]

The fauna of the Dents du Midi is, as in the whole of the Valais Alps, mainly composed of chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), marmots (Marmota) and alpine ibex (Capra ibex). It also includes various species of birds, such as the wallcreeper (Tichodroma muraria), the rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta), the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) and sometimes the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus). Approximately 40,000 fry are introduced each year into Lac de Salanfe, where fishing is permitted.[26] Finally, herds of cows are sometimes pastured around the lake.[27][28]

History

editThe Val d'Illiez has been inhabited since ancient history, but it was not until the end of the 18th century that the first recorded ascents of the Dents du Midi were made. In ancient times, the mountains inspired awe and were sometimes considered to be inhabited by the Devil.[29] In 1784, the vicar of Val-d'Illiez, Jean-Maurice Clément, a passionate mountaineer, became the first to climb the Haute Cime.[30] In 1832, the priest of Val-d'Illiez Jean-Joseph Gillabert had the first Christian cross installed at the summit of the Haute Cime.[31] Ten years later, on August 16, 1842, an expedition led by Nicolas Délez and including canon Bruchon of Saint-Maurice Abbey and four other people made the first ascent of the Cime de l'Est. Having set off from the mountain pasture of Salanfe, canon Bruchon declared in a text for the Gazette du Simplon that he had gone through "a thousand difficulties" to reach the summit, but described the view as "the most ravishing spectacle". The conditions being very difficult, the Cime de l'Est was climbed very little during the rest of the 19th century. Some had to climb it several times before they succeeded, and the bells of the church of Salvan rang every time someone reached the summit. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, this tradition came to an end, as there were now more than a hundred climbs a year.[32]

On June 7, 1870, the writer and mountaineer Émile Javelle, accompanied by a guide, was the first to reach the summit of the Forteresse. The Dent Jaune was climbed for the first time on August 24, 1879. The climb, which lasted only one day, was led by guides Fournier and Bochatay. The ascent was made easier by the proximity of the Alpe de Salanfe, where one can take refuge in case of difficulties. Two years later, on August 31, 1881, Auguste Wagnon, Beaumont and their guide Édouard Jacottet achieved the first ascent of the Cathédrale.[33] Les Doigts were climbed in two stages: first the Doigt de Champéry in 1886 by Wagnon, Beaumont and a guide, then the Doigt de Salanfe by Breugel and his guide in 1892. The last summit to be climbed was the Éperon, on August 8, 1892, by Janin and his guide.[34]

In 1902, during the topographical levelling of Switzerland for the Federal Office of Topography, Heinrich Wild, the founder of Wild Heerbrugg, found himself in a storm at the top of the Dents du Midi. As the equipment was heavy and difficult to transport, he was unable to complete the measurement and had to leave the site in an emergency. This event motivated him to design an easily transportable theodolite. The tool represented a revolution in the field of geomatics and is still in use in the 21st century.[35] In 1942, the Alpine Club of Saint-Maurice celebrated the centenary of the first ascent of the Cime de l'Est by erecting a metal cross at the top of the tooth.[36]

On December 23, 1970, the guides Werner Kleiner and Marcel Maurice Demont made the first winter ascent of the Cime de l'Est, the Forteresse and the Cathédrale.[37] On March 2, 1980, Beat Engel and Armand Gex-Fabry, respectively a ski teacher and an employee of Télé-Champoussin, made the first winter ski descent of the Doigts couloir. They set off at 2 a.m. from a hamlet above Salvan, and the effort represented thirteen hours of ascent for two hours of descent.[38] In 1981, Engel and Diego Bottarel, also a ski teacher, attempted to reach the summit of the Haute Cime in a hot air balloon and then descend the Couloir des Doigts. The attempt was unsuccessful, however, as the weather conditions did not allow them to land.[39]

Activities

editSports tourism

editSeveral dozen kilometres of trails are available on the Dents du Midi. The "trail des Dents du Midi", a foot race created in 1961 by Fernand Jordan, took place every year in mid-September between 1963 and 2000, and restarted in 2011. The race is 57 kilometers (35 mi) long with 3,700 metres (12,100 ft) of ascent; it is the first of its kind in Europe and the precursor of trail running.[40] In 1975, the success of the trail led to the creation of a footpath going around the Dents du Midi.[41] This 42.5 kilometers (26.4 mi) footpath offers a total difference in height of 6,000 meters (20,000 ft) and is accessible from Champéry, les Cerniers, Mex, Salvan and Vérossaz. Nine refuges are situated on the tour and allow the 18-hour walk to be completed in several days.[42] Since 2010, the paths have been maintained by the "Tour des Dents du Midi" association. This association brings together nearby communes as well as the people in charge of the refuges and local guides.[43]

Access to the summits of the Dents du Midi is possible in summer in the form of a trek and in winter by ski touring or mixed climbing.[44] The normal route to the Cime de l'Est starts from the Dents du Midi refuge (2,884 metres; 9,462 ft), on the southern face, crossing the Plan Névé glacier. About a hundred metres after the Cime de l'Est pass, which is no longer used because it is blocked by scree, it climbs a mountainside, either by taking the Rambert couloir, which may be snow-covered, or by going around it. At the top of this couloir there is a path on the north face of the hillside which ends about twenty meters below the summit. The summit can also be reached from the Chalin hut (2,595 metres; 8,514 ft) by climbing the northeast face of the Cime de l'Est or by climbing the Harlin pillar.[45] The normal route to the Forteresse is similar to that of the Cathédrale. It starts from the Chalin hut on the northern face, joins the mountain pasture of the same name and climbs the ridge of Soi before arriving in the Forteresse-Cathédrale corridor. From the top of the corridor, known as the "Fenêtre de Soi", both peaks are accessible for climbing. The "Fenêtre de Soi" is also accessible on foot from the Dents du Midi refuge.[46] Access to the Dent Jaune is via the "Vire des Genevois". This route starts from the Dents du Midi refuge, crosses the Plan Nevé glacier to the Dent Jaune pass, follows the peak on a bend and then follows the ridge to the summit of the Dent Jaune.[47] The normal route of the Haute Cime starts at the Susanfe hut (2,102 metres; 6,896 ft), follows the Saufla torrent to the Susanfe pass and crosses scree to the summit.[46]

Economy

editThe emergence of tourism in the 19th century saw several hotels open in the villages of the Val d'Illiez. As early as 1857, the construction of the Grand Hôtel de la Dent du Midi enabled Champéry to expand, the image of the Dents du Midi being widely used to promote the village. Outside the Val d'Illiez, the villages of Bex, Gryon and Leysin also used the relief of the Dents du Midi in their promotional material, as did certain hotels on the Swiss shores of Lake Geneva.[48] In 2018, the communes of Champéry, Troistorrents and Val-d'Illiez joined forces with the Portes du Soleil and other local associations to create a tourism management body in the name of Région Dents du Midi. Its main aim is to unify the tourism development policy of the Val d'Illiez.[49]

The 7 Peaks brewery, located in Morgins, bases its brand on the image of the Dents du Midi. Its name refers to the seven peaks of the chain, which give their name to the seven styles of beer on offer.[50]

Environmental protection

editThere are two protected sites on the north-eastern face of the Dents du Midi: the Aiguille and the Teret. These areas of 4 hectares (48,000 sq yd) each were classified in 2017 with the aim of protecting Switzerland's dry meadows and pastures from agricultural use, almost 95% of which have disappeared since 1900.[51]

Culture

editThe Dents du Midi are represented in painting by many artists, most often as a backdrop for paintings of villages, Lake Geneva or Chillon Castle, but also alone.[52]

They are also described or mentioned by Étienne Pivert de Senancour in Oberman (1804), Alexandre Dumas in Impressions de voyage en Suisse (1834), Eugène Rambert in Les Alpes suisses (1866) and Bex et ses environs (1871), Émile Javelle in Souvenirs d'un alpiniste (1886), Maurice Bonvoisin in La vie à Champéry (1908) and finally Charles Ferdinand Ramuz in La guerre dans le Haut-Pays (1915) and Vendanges (1927).[53]

The Dents du Midi can be found on the coat of arms of the commune of Val-d'Illiez as well as on the 10 farinets banknotes, a local currency of the Valais named after Joseph-Samuel Farinet, which circulated between 2017 and 2019.[54]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Carte de la Suisse". Swisstopo (in French). Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Retrieved from the Swisstopo topographic maps. The key col is the Col des Montets (1,461 m).

- ^ Retrieved from Google Earth. The nearest point of higher elevation is north of the Aiguille du Génépi (Mont Blanc massif).

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Plantin (1656). Helvetia antiqua et nova (in Latin). Zurich. p. 45.

- ^ a b "L'origine des noms". lesdentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Recul des glaces". Études hydrologiques et géologiques (in French). 7 July 2017. p. 1. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Vallauri 1998, p. 39.

- ^ Bérody, Gaspard; Bourban, Pierre (1894). Imprimerie Catholique Suisse (ed.). Le Mystère de St-Maurice (PDF) (in Latin). Fribourg. p. 148.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Les dents du Midi - Montreux - Swiss Riviera". fusions.ch. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Carte de la Suisse". Office fédéral de topographie swisstopo. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Région des dents du Midi - Pentes Raides et Couloirs". Chablais Grimpe (in French). Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Haute Cime, randonnée". www.visinand.ch (in French). 15 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Les dents du Midi en trois histoires géologiques". lesdentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Jean-Luc Epard (1990). Imprimerie Chabloz (ed.). "La nappe de Morcles au sud-ouest du Mont-Blanc". Mémoires de Géologie (Lausanne) (in French). Lausanne: 5. ISSN 1015-3578. S2CID 131231932.

- ^ Charles Ducloz (1944). Les flyschs des dents du Midi (in French). p. 8.

- ^ Ernest Favre; Hans Schardt (1887). Description géologique des Pré-alpes du canton de Vaud et du Chablais jusqu'à la Dranse et de la chaîne des dents du Midi formant la partie nord-ouest de la feuille XVII (in French). Berne: Francke et Co. p. 573.

- ^ "Lac de Soi". www.regiondentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Jean Sesanio (January 2003). "Traçage entre le lac de Salanfe et les sources de Val d'Illiez (Valais, Suisse)". Karstologia (in French). No. 41. pp. 49–54. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Carte des zones sismiques de Suisse". map.geo.admin.ch (in French). 2 January 2003. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Frédéric Montandon (1926). "Le Réveil de la dent du Midi". Le Globe. Revue Genevoise de Géographie (in French). 66 (1): 15. doi:10.3406/globe.1927.2439.

- ^ "Gros éboulement aux dents du Midi". www.rts.ch (in French). 30 October 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Climat Plateau Rosa". www.meteoblue.com (in French). Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Chablais et Préalpes, entonnoirs de la Suisse ?". www.meteosuisse.admin.ch (in French). 23 November 2017. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Swiss national map". Swisstopo. Swiss Confederation. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ "Vogealle à Salanfe : la flore". www.tourduruan.com (in French). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "La pêche à Salanfe". www.salanfe.ch (in French). 20 January 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Vogealle à Salanfe : la faune". www.tourduruan.com (in French). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Les dents du Midi". www.regiondentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "La première ascension de la Haute Cime". www.salanfe.ch (in French). 28 March 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Tamini & Delèze 1924, p. 325.

- ^ Tamini & Delèze 1924, p. 316.

- ^ Christian Zarn (1942). "La croix sur la cime de l'Est". In Abbaye de Saint-Maurice (ed.). Les échos de Saint-Maurice (PDF) (in French). Saint-Maurice.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Club alpin français (January 1882). Typographie Georges Chamerot (ed.). Bulletin (in French). Paris. p. 18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vallauri 1998, p. 40.

- ^ F. Staudacher (4 December 2003). "Technologierevolution vor 100 Jahren auf den Dents-du-Midi". Géomatique Suisse : géoinformation et gestion du territoire (in German) (101 ed.). p. 713. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "La croix sur la cime de l'Est des dents du Midi". Le Nouvelliste (in French). 2 August 1942. p. 3. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Marcel Maurice Demont (20 February 2019). "Première hivernale aux dents du Midi". www.notrehistoire.ch (in French). Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Descente à ski du couloir des Doigts". Le Nouvellise (in French). 3 March 1980. p. 3. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "Vers un exploit ?". Le Nouvellise (in French). 8 January 1982. p. 21.

- ^ "Histoire du Trail". ddmtrail.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Le tour pédestre des Dents-du-Midi". Le Nouvelliste (in French). 9 July 1975. p. 13. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Le tour des dents du Midi". www.dentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Lise-Marie Terrettaz (22 June 2010). "Pour faire vivre le Tour". Le Nouvelliste (in French). p. 33. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Dents du Midi". www.camptocamp.org (in French). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Cime de l'Est". www.camptocamp.org (in French). Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Sommets des Dents du Midi". www.hcaloz-guide.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Dent Jaune : Vire aux Genevois". www.camptocamp.org (in French). Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Dents du Midi - Images d'hier - Affiches". www.lesdentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Fabrice Zwahlen (30 March 2018). "Les dents du Midi prennent de l'altitude". www.lenouvelliste.ch (in French). Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Quand la Suède et l'Italie partent à l'assaut des Dents-du-Midi". www.24heures.ch (in French). 9 September 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Prairies et pâturages secs". www.bafu.admin.ch (in French). Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Les peintures des dents du Midi". lesdentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Les poètes". lesdentsdumidi.ch (in French). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "La monnaie locale "farinet" lancée en Valais avec 500'000 billets imprimés". www.rts.ch (in French). 13 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

Bibliography

edit- Tamini, Jean-Émile; Delèze, Pierre (1924). Imprimerie Saint-Augustin (ed.). Essai d'Histoire de la Vallée d'Illiez (PDF) (in French). Saint-Maurice. p. 420.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vallauri, Daniel (1998). Édition Pillet (ed.). Voyage en val d'Illiez (in French). Vol. 1. Saint-Maurice. p. 129. ISBN 2-940145-03-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)