Melungeon

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Cumberland Gap and surrounding counties | |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Baptist | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| undetermined |

Melungeon is a term traditionally applied to one of a number of so-called "tri-racial isolate" groups of the Southeastern United States, found mainly in the Cumberland Gap area of central Appalachia: eastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, and eastern Kentucky. "Tri-racial" refers to populations of mixed European, sub-Saharan African, and Native American ancestry, and "isolate" refers to "genetic isolate," that is, a group that has maintained to some degree a distinct ethnic identity, though is not necessarily isolated in a geographic or cultural sense. Although there is no consensus on how many such groups exist, estimates range as high as 200. [1] Some self-identifying Melungeons dislike the term "tri-racial isolate", believing that it has pejorative connotations, although the term "Melungeon" itself was considered pejorative until the late 20th century.

Melungeons are a highly controversial subject, and there is wide disagreement among secondary sources as to their ethnic, linguistic, cultural and geographic origins and identity. Whether Melungeons constitute a specific race or ethnicity at all is debatable, and they might more accurately be described as a loose collection of families of diverse origins who migrated alongside and intermarried with one another. Melungeon is not a separate category on the census, but is tabulated under the "SOME OTHER RACE 600-999" category as a result of respondents writing it in. For the 2000 Census it was "662 Melungeons".[2]

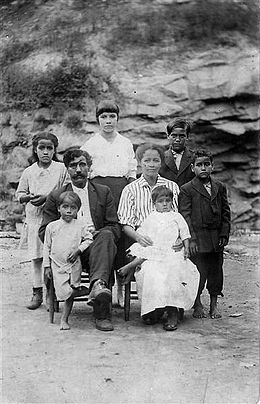

Melungeons are defined as having racially mixed ancestry, thus do not exhibit characteristics which can be incontrovertibly classified as being of a single racial phenotype. Most modern-day descendants of Appalachian families traditionally regarded as Melungeon are generally Caucasian in appearance, often, though not always, with dark hair and eyes, and a swarthy or olive complexion. Descriptions of Melungeons vary widely from observer to observer, from "Middle Eastern" to "Native American" to "light-skinned African American."

A major factor in the wide variation in descriptions is the lack of a clear consensus on exactly who should be included under the term Melungeon. Almost every author on this subject gives a slightly different list of Melungeon-associated surnames, but the British surnames Collins and Gibson appear most frequently (genealogist Pat Elder calls them "core" surnames). Many researchers also include Bowling, Bunch, Denham, Dunaway, Goins, Goodman, Minor, Mise, Moore, Mullins, Williams, Wise, and several others (though this does not mean that all families with these surnames are Melungeon). Not all of these families were necessarily of the same racial background, and each line should be examined individually. Ultimately, the answer to the question "Who or what are Melungeons?" depends largely on which families are included under that designation.

The original meaning of the word "Melungeon" is obscure (see Etymology below), but from about the mid-19th to the late 20th centuries, it referred exclusively to one tri-racial isolate group, the descendants of the multiracial Collins, Gibson, and a few other related families of Newman's Ridge, Vardy Valley and other settlements in and around Hancock County, Tennessee. Some researchers limited it even further to the descendants of two early 19th century settlers of that area, Vardy Collins and his brother-in-law Shepherd Gibson. Recently, however, some researchers have begun to use Melungeon as a catch-all term encompassing almost all traditionally recognized tri-racial isolate groups of the Eastern United States.

Origins

A common belief about the Melungeons of Eastern Tennessee is that they are an indigenous people of Appalachia, existing there before the arrival of the first white settlers. However, as evidenced by a range of tax, court, census and other records, the ancestors of the Melungeons followed the same migration paths into the region as their English, Scots-Irish, and German neighbors.

The likely background to the mixed-race families later to be designated as "Melungeons" was the emergence in the Chesapeake Bay region in the 17th century of what historian Ira Berlin (1998) calls "Atlantic Creoles." These were freed slaves and indentured servants of European, West African, and Native American ancestry (and not just North American, but also Caribbean, Central and South American Indian: see Forbes (1993)). Some of these "Atlantic Creoles" were culturally what today might be called "Hispanic" or "Latino," bearing names such as "Chavez," "Rodriguez," and "Francisco." Many of them intermarried with their English neighbors, adopted English surnames, and even owned slaves. Early Colonial America was very much a "melting pot" of peoples, but not all of these early multiracial families were necessarily ancestral to the later Melungeons.

Genealogists Dr. Virginia E. DeMarce and Paul Heinegg, as well as Melungeon descendant Jack Goins, have traced the "core" Gibson and Collins families back to Louisa County, Virginia in the early 1700s. [3], [4] , [5] These families were of mixed European and African, and possibly also of Native American, heritage, and are identified as "mulattos" and "blacks" in subsequent records. The Gibson family can be traced back even further to Charles City County, Virginia in the late 17th century. According to genealogist Paul Heinegg, the Gibson family probably derived from Elizabeth Chavis, whose descendants are called "mulattos" and "negros."[6] The Chavis family was an early and large mixed-race family in several Eastern Virginia and North Carolina counties. Today, Chavis and its variants (originally Chavez) is one of the most widespread of the surnames associated with "tri-racial isolate" groups in the Eastern U.S., though it is not a typical Melungeon surname.

These families migrated in the first half of the 18th century from Virginia to North and South Carolina. The Collins, Gibson, and Ridley (Riddle) families owned land adjacent to one another in Orange County, North Carolina, where they and the Bunch family were "free Molatas (mulattos)" taxable on "Black" tithes in 1755. [7], [8]

Beginning about 1767, the ancestors of the Melungeons moved northwestwards to the New River area of Virginia [9], where they are listed on tax lists of Montgomery County, Virginia, in the 1780s. From there they migrated down the Appalachian Range to Wilkes County, North Carolina, where they are listed as "white" on the 1790 census. [10] They resided in a part of that county which became Ashe County, where they are designated as "other free" in 1800.[11]

Not long after, Melungeon Collins and Gibson families were members of Stony Creek Primitive Baptist Church in nearby Scott County, Virginia, where they appear to have been treated as social equals of the white members. The earliest documented use of the term "Melungeon" is found in the minutes of this church (see Etymology below).[12]

From Virginia and North Carolina they crossed into Kentucky and Tennessee. The earliest known Melungeon in Northeast Tennessee was Millington Collins, who executed a deed in Hawkins County in 1802.

Several Collins and Gibson households appear in Floyd County, Kentucky, in 1820, when they are listed as "free persons of color". [13] On the 1830 censuses of Hawkins and Grainger County, Tennessee, Melungeon families are listed as "free-colored." [14], [15] Melungeons were residents of the part of Hawkins that became Hancock County in 1844.[16]

Despite migrating alongside the early European settlers of Appalachia, it is obvious that the pre-20th century Melungeons were not of purely European ancestry themselves. Over the course of the 18th and early 19th centuries, they were most frequently designated as "mulatto," "other free," or as "free persons of color." Sometimes they were listed as "white," sometimes as "black" or "negro", but almost never as "Indian." One family described as "Indian" was the Melungeon-related Ridley family, listed as such on a 1767 Pittsylvania County, Virginia tax list,[17] though they had been designated "mulattos" in 1755. [18] During the 19th century, the Melungeon families begin to be counted with increasing frequency as white on census records, and have largely continued to be so up to the present [19], but even in 1935, they were still being described as "mulattoes" with "straight hair."[20]

Kennedy (1994) characterizes this gradual change of the Melungeons from a "mulatto" to a "white" population as an "ethnic cleansing." However, the historical evidence reveals that these families facilitated their own assimilation through voluntary intermarriage with whites, leading to an increasingly lighter appearance among descendants.

A second important factor in this shift from "mulatto" to "white" was the often imprecise and ambiguous definitions of the racial categories "mulatto" and "free person of color." In the British North American colonies and the United States at various times in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries "mulatto" could mean a mixture of African and European, African and Native American, European and Native American, or all three, as documented by historian Jack D. Forbes (1993). This loose terminology could sometimes lead to wholesale reclassifications of indigenous peoples, as in the case of the Indians of Delaware.[21]

The families known as "Melungeons" in the 19th century were generally well integrated into the communities in which they lived, though this is not to say that racism was never a factor in their social interactions. However, records show that on the whole they enjoyed the same rights as whites. For example, they held property, voted, and served in the Army; some, such as the Gibsons, had even owned slaves in the 18th century.[22]

On the other hand, several Melungeon men were tried in Hawkins County, Tennessee, in 1846 for "illegal voting." They were acquitted, presumably by demonstrating to the court's satisfaction that they had no African ancestry. Melungeon ancestry was questioned again in an 1872 trial in Hamilton County, Tennessee. This case questioned the legitimacy of a marriage between a white man and a Melungeon woman, and once again a court decided that the Melungeons were not of African ancestry.[23]

Modern anthropological and sociological studies of Melungeon descendants in Appalachia have demonstrated that they are culturally indistinguishable from their "non-Melungeon" white neighbors, sharing their Baptist religious affiliation and other features. The descendants of the early Melungeon pioneer families are not confined to Appalachia, however. Today, many people throughout the United States can legitimately claim this ancestry.

Legends

In spite of being culturally and linguistically identical to their white neighbors, these multiracial families were of a sufficiently different physical appearance to invite speculation as to their identity and origins. Sometime during the first half of the 19th century, the pejorative term "Melungeon" began to be applied to these families, thus effectively creating an ethnic group that did not previously exist. It would therefore be anachronistic to speak of "Melungeons" prior to that period. Local traditions soon began to arise about this "people" who lived in the hills of Eastern Tennessee. According to Pat Elder, the earliest of these was that they were "Indian" (often specifically "Cherokee"). Melungeon descendant Jack Goins states, however, that the Melungeons themselves claimed to be both Indian and "Portuguese." One early Melungeon was called "Spanish" ("Spanish Peggy" Gibson, wife of Vardy Collins).

Despite the scant evidence, Iberian (Spanish and/or Portuguese) and Native American ancestry are both possible given the history of multiracial families in the Melungeons' time and place of origin (late 17th century-early 18th century Eastern Virginia). However, claims about such ancestry made by Melungeon descendants in the 19th century or later should not necessarily be taken at face value. Many Southern families with multiracial ancestry have claimed Portuguese or American Indian (specifically Cherokee) ancestry as a strategy for denying any African ancestry.

Although the available historical evidence makes a specific tribal origin such as Cherokee highly unlikely for the original Melungeon families, some of their descendants may have later intermarried with families of Cherokee ancestry in Eastern Tennessee. Anthropologist E. Raymond Evans (1979), regarding the Cherokee claims of the Melungeons of Graysville, Tennessee, writes:

- "In Graysville, the Melungeons strongly deny their Black heritage and explain their genetic differences by claiming to have had Cherokee grandmothers. Many of the local whites also claim Cherokee ancestry and appear to accept the Melungeon claim...."[24]

A much more recent claim of a specific tribal origin for Melungeons is Saponi, an early Virginia Siouan tribe. Elder (1999) suggests that the Saponi and other tribes who resided for a time at Fort Christanna in Virginia may have been a component of Melungeon ancestry. Historian C. S. Everett initially hypothesized that John Collins the Sapony Indian, who was expelled from Orange County, Virginia about January 1743 for firing at a white planter, might be the same man as the Melungeon ancestor John Collins, called a "mulatto" in 1755 North Carolina. However, Everett has subsequently revised that position. These were two different men, and only the latter has any proven connection to the Melungeons (see also [25]). Another frequently suggested source of Melungeon ancestry is Powhatan, a group of tribes inhabiting Eastern Virginia when the English arrived.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, speculation on Melungeon origins continued, producing tales of shipwrecked sailors, lost colonists, hoards of silver, and ancient peoples such as the Carthaginians. With each author, more elements were added to the mythology surrounding this group, and more peoples were added to the list of possible Melungeon ancestors. The most influential of these early authors was probably Will Allen Dromgoole, who wrote several articles on the Melungeons in the 1890s.[26] More recent suggestions by amateur researchers as to the Melungeons' ethnic identity include Gypsy, Turkish, and Jewish, but there is no evidence that Melungeons themselves ever claimed any of those ancestries.

In addition, there is also a theory that the Melungeons are descendants of the members of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island, North Carolina, which was established in 1587.

Currently, a casual reader of Internet sources on this group might be left with the impression that there exists in the hills of Eastern Tennessee an enclave of people, probably of Mediterranean or Middle Eastern origin, who have been in the area since before the arrival of the first white settlers. Such romantic fictions find no support among academic historians and genealogists, however. Virginia E. DeMarce, former president of the National Genealogical Society, and author of several articles on the Melungeons, said in a 1997 interview: "It's not that mysterious once you...do the nitty gritty research one family at a time...basically the answer to the question of where did Tennessee's mysterious Melungeons come from is three words. And the three words are Louisa County, Virginia."

Etymology

There are many hypotheses about the etymology of the term "Melungeon". Kennedy (1994) speculates that it derives from the Turkish melun can (from Arabic "mal`un jinn" ملعون جنّ) which means "damned soul". Another theory traces the word to malungu, a Luso-African root from Angola meaning "shipmate."[27] One theory, long favored by linguists and many researchers on the topic and found in several dictionaries, is that it derives from the French mélange, or mixture. An underlying assumption in many suggested etymologies seems to be that "Melungeon" and the people designated by that term have a common origin. For example, Kennedy believes this group to be at least partly of Turkish origin; thus, for him, their name must also be Turkish.

The earliest known written use of the word "Melungeon" is in an 1813 Scott County, Virginia Stony Creek Primitive Baptist Church record:

- "Then came forward Sister Kitchen and complained to the church against Susanna Stallard for saying she harbored them Melungins. Sister Sook said she was hurt with her for believing her child and not believing her, and she won't talk to her to get satisfaction, and both is 'pigedish', one against the other. Sister Sook lays it down and the church forgives her."

The usage of this word in the minutes without definition suggests it was a word familiar to the congregation, and appears at first glance to refer to a group of people: this is how Goins (2000) and others read it. However, such a reading seems at odds with the fact that several Melungeons were at the time members of the church, namely Thomas and Charles Gibson and Valentine Collins. Also, there is no record of any group called "Melungeons" prior to this time. As suggested by Joanne Pezzullo and Karlton Douglas,[28] a more likely derivation for "Melungeon" could be from the now obsolete English word "malengin" (also spelled "mal engine") meaning "guile," "deceit," or "ill intent," and used as the name of a trickster figure by Edmund Spenser in his epic poem The Faerie Queene. Thus, the phrase "harbored them Melungins" would be equivalent to "harbored someone ill will," or could mean "harbored evil people" without reference to ethnicity. Judging by these church minutes, then, it appears that the families who would later be called "Melungeons" in Tennessee were not yet known by that term in 1813 Virginia.[29]

By 1840 "Melungeon" had apparently become a racial pejorative, at least in Tennessee: a Jonesborough, Tennessee, newspaper article of that year entitled "Negro Speaking!" refers to a competing politician in derogatory fashion first as "an impudent Malungeon from Washington Cty, a scoundrel who is half Negro and half Indian," then as a "free negroe".[30]. Since Washington County borders Hawkins, the term "Melungeon" was presumably already associated by that time with Northeast Tennessee. However, it is unclear whether the word referred to a specific set of families or was just a generic label for a certain category of African American. The article does not provide the politician's name, but the 1830 census for Washington County, Tennessee lists the names of several free colored families, including several surnamed Hale.[31] Hale is listed by DeMarce (1992) as a Melungeon surname, but Elder (1999) finds no evidence that they were connected to the core Collins and Gibson families. By the mid-to-late 19th century, at least, it seems clear the term referred specifically to the multiracial families of Hancock County and neighboring areas.

There seems to be no written evidence to demonstrate the process whereby a word meaning "ill will" in 1813 had come to mean a "half Negro ... half Indian" or "free negroe" by 1840. Even today, though, some people in Eastern Tennessee still use the term to mean something like "boogeyman," suggesting a possible intermediate stage.

Several other uses of the term from mid-19th to early 20th century print media have been collected at this Website. As can be seen, the spelling of the term varied somewhat from author to author, until eventually the form "Melungeon" became standard.

Modern identity

The term "Melungeon" was traditionally considered an insult, a label applied to Appalachian whites who were by appearance or reputation of mixed-race ancestry, though who were not clearly either "black" or "Indian". In Southwest Virginia, the roughly synonymous term "Ramp" was also used, though this term has never shed its pejorative character. Thanks to a play, however, "Melungeon" began about the late 1960s to lose this negative connotation, and become a self-applied designation of ethnicity.

As described in a 1968 Kingsport, Tennessee newspaper article,[32] this shift in meaning was probably due largely to the presentation of playwright Kermit Hunter's outdoor drama Walk Toward the Sunset. This play about Melungeons was first presented in 1969 in Sneedville, Tennessee, the county seat of Hancock County. It makes no claims to historical accuracy, and portrays the Melungeons as an indigenous people of uncertain race who are wrongly perceived as black by the white settlers. Thanks to the increased interest in Melungeon history that this drama sparked, as well as its painting of Melungeons in a positive, even romantic, light, many individuals began for the first time to self-identify as Melungeons. As the newspaper article relates, the purpose of the drama was "to improve the socio-economic climate" of Hancock County, and to "lift the Melungeon name 'from shame to the hall of fame'". The increasing acceptance of non-white minority groups by white Americans in the wake of the social changes of the 1960s was also likely a factor in this shift.

Interest in the group has grown tremendously since the mid-1990s due to the publication of a short chapter in Bill Bryson's The Lost Continent, N. Brent Kennedy's popular book on his claimed Melungeon roots, as well as to the Internet, where numerous websites devoted to the "mysterious" Melungeons may be found. Together with this growth in interest, and perhaps because of it, the number of individuals claiming Melungeon heritage has vastly increased. Many newly self-identifying Melungeons have no demonstrable connections to the families historically known by that term, and often had been completely unaware of either the term or the group until encountering them on the Internet.

Some individuals begin to self-identity as Melungeons only after reading about this group on a website, and finding that their surname is on an ever-growing list of "Melungeon-associated" surnames, or they have certain physical traits or conditions purportedly indicative of such ancestry.[33] For example, Melungeons are allegedly identifiable by "shovelled incisors," a dental feature very common among, but not restricted to, Native Americans and Northeast Asians.[34] A second feature attributed to Melungeons is an enlarged external occipital protuberance, dubbed an "Anatolian Bump" after the fact that this feature appears among Anatolian Turks with higher frequency than in other populations. This latter notion stems from the hypothesis, popularized by N. Brent Kennedy, that Melungeons are of Turkish origin.

Another claim found often on the Internet is that Melungeons are more prone to certain diseases, such as sarcoidosis or familial Mediterranean fever.[35] The ostensible prevalence of such diseases among Melungeons is presented by some as proof that they are of Mediterranean ancestry, though neither of those diseases is confined to a single population.[36],[37] The "disease" claim originated with N. Brent Kennedy, who began his quest into Melungeon origins after himself being diagnosed with sarcoidosis, though his own connections to this group are a matter of debate. In her review of his 1994 book, genealogist Virginia E. DeMarce finds no evidence that Kennedy is actually of Melungeon ancestry: [38]. Kennedy responds to her critique in this article: [39].

Claims that certain physical traits and conditions are more prevalent among Melungeon families rest on anecdotal evidence, however, and are not supported by any scientific research.

DNA testing

At the suggestion of N. Brent Kennedy, a DNA study on Melungeons was carried out in 2000 by Dr. Kevin Jones, using 130 hair and cheek cell samples. These samples were taken from subjects who were largely chosen by Kennedy himself as representative of Melungeon lines. McGowan (2003) describes Dr Jones' apparent frustration with the study, which caused disappointment among some observers. "...Jones concluded that the Melungeons are mostly Eurasian, a catchall category spanning people from Scandinavia to the Middle East. They are also a little bit black and a little bit American Indian."[40] This study has to date not been submitted to a peer-reviewed scientific journal, nor has a list of those contributing samples been published; thus, it is unclear to what extent the subjects were actually descendants of families historically designated as "Melungeon."

More recently, Jack Goins has started a Melungeon DNA Project, with the goal of studying the ancestry of hypothesized Melungeon lines. Y chromosomal DNA testing [41] of male subjects with the Melungeon surnames Collins, Gibson, Goins, Bunch, Bolin, Goodman, Williams, Minor and Moore has revealed evidence of European and sub-Saharan African ancestry: Y haplogroups R1b, R1a, J2; and E3a, respectively.[42] One Goings line looks likely to be a variety of Y haplogroup L with roots in Portugal, Spain and Italy. Taken as a whole, such findings appear to verify the early designation of Melungeon ancestors as "mulattos."

Similar groups

Other so-called "tri-racial isolate" populations include the:

- Lumbee of North Carolina

- Person County Indians aka "Cubans and Portuguese" of North Carolina

- Goinstown Indians in Rockingham, Stokes, and Surry counties of North Carolina

- Goins of Rhea, Roane, and Hamilton counties of eastern Tennessee

- Monacan Indians aka "Issues" of Amherst and Rockingham Counties, Virginia

- Magoffin County People of Kentucky (Magoffin and Floyd counties)

- Carmel Indians of Ohio (Highland County)

- Brown People of Kentucky

- Guineas (ethnic group) of West Virginia

- Chestnut Ridge people of Philippi, West Virginia

- We-Sorts of Maryland

- Nanticoke-Moors of Delaware

- Turks and Brass Ankles of South Carolina

- Redbones of South Carolina (note: as distinct from Gulf States Redbones).

- Dead Lake People of Gulf and Calhoun counties Florida

- Ramapough Mountain Indians aka "Jackson Whites" of the Ramapo Mountains of New York and New Jersey

- Dominickers of Holmes County in the Florida Panhandle

Each of these groupings of mixed-race populations has a particular history, and there is evidence for connections between some of them. The Goins group has long been identified as Melungeons by people from the rest of Tennessee, and the surname Goins is also found among the Lumbees.

Sociologist Brewton Berry (1963) used the term "Mestizo" for these groups, but that alternative has not been generally adopted.

In his Foreword to the section on Virginia, North, and South Carolina in Heinegg's work on free African Americans, historian Ira Berlin sums up the history of such groups thus:

- "Heinegg's genealogical excavations reveal that many free people of color passed as whites--sometimes by choosing ever lighter spouses over succeeding generations. Even more commonly, they claimed Indian ancestry. Some free people of color invented tribal designations out of whole cloth. Here Heinegg, entering into an area of considerable controversy, explodes what he declares the "fantastic" claims of many so-called tri-racial isolates." [43]

References

- Ball, Bonnie (1992). The Melungeons (Notes on the Origin of a Race). Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press.

- Berlin, Ira (1998). Many Thousands Gone : The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Berry, Brewton (1963). Almost White: A Study of Certain Racial Hybrids in the Eastern United States. New York: Macmillan Press.

- Bible, Jean Patterson (1975). Melungeons Yesterday and Today. Signal Mountain, Tennessee: Mountain Press.

- DeMarce, Virginia E. (1992). "Verry Slitly Mixt': Tri-Racial Isolate Families of the Upper South - A Genealogical Study." National Genealogical Society Quarterly 80 (March 1992): 5-35.

Bryson, Bill. (1989). The Lost Continent : Travels in Small Town America.

- DeMarce, Virginia E. (1993). "Looking at Legends - Lumbee and Melungeon: Applied Genealogy and the Origins of Tri-Racial Isolate Settlements." National Genealogical Society Quarterly 81 (March 1993): 24-45.

- DeMarce, Virginia E. (1996). Review of The Melungeons: Resurrection of a Proud People. National Genealogical Society Quarterly 84 (June 1996): 134-149.

- Dromgoole, Will Allen (1890). "Land of the Malungeons" Nashville Daily American, newspaper, writing under the name Will Allen, August 31, 1890: 10. Article available at: [44]

- Elder, Pat Spurlock (1999). Melungeons: Examining an Appalachian Legend. Blountville, Tennessee: Continuity Press.

- Evans, E. Raymond (1979). "The Graysville Melungeons: A Tri-racial People in Lower East Tennessee." Tennessee Anthropologist IV(1): 1-31.

- Everett, Christopher (1998). "Melungeon Historical Realities: Reexamining a Mythopoeia of the Southern United States". Conference paper, Conference on Innovative Perspectives in History. Blacksburg, Virginia: Graduate Program, Department of History, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, April 17-18, 1998.

- Forbes, Jack D. (1993). Africans and Native Americans The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples. University of Illinois Press.

- Goins, Jack H. (2000). Melungeons: And Other Pioneer Families. Blountville, Tennessee: Continuity Press.

- Heinegg, Paul (2005). FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS OF VIRGINIA, NORTH CAROLINA, SOUTH CAROLINA, MARYLAND AND DELAWARE Including the family histories of more than 80% of those counted as "all other free persons" in the 1790 and 1800 census. Available in its entirety online at freeafricanamericans.com

- Johnson, Mattie Ruth (1997). My Melungeon Heritage: A Story of Life on Newman’s Ridge. Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press.

- Kennedy, N. Brent, with Robyn Vaughan Kennedy (1994). The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

- Langdon, Barbara Tracy (1998). The Melungeons: An Annotated Bibliography: References in both Fiction and Nonfiction. Hemphill, Texas: Dogwood Press.

- McGowan, Kathleen (2003). "Where do we really come from?" DISCOVER 24 (5, May 2003). Available at [45]

- Offutt, Chris. (1999) "Melungeons." Italic textOut of the WoodsItalic text" Simon & Schuester.

- Price, Edward T. (1953). "A Geographic Analysis of White-Negro-Indian Racial Mixtures in Eastern United States." The Association of American Geographers. Annals 43 (June 1953): 138-155. [46]

- Price, Henry R. (1966). "Melungeons: The Vanishing Colony of Newman's Ridge." Conference paper. American Studies Association of Kentucky and Tennessee. March 25-26, 1966.

- Vande Brake, Katherine (2001). How They Shine: Melungeon Characters in the Fiction of Appalachia. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

- Williamson, Joel (1980). New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States. New York: Free Press.

- Winkler, Wayne (2004). "Walking Toward the Sunset: The Melungeons of Appalachia." Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. [47]

- Winkler, Wayne (1997). "The Melungeons." All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 21 Sept. 1997.

See also

External links

- The Official Website of The Melungeon Heritage Association.

- Jack Goins Research Study of Melungeon and Appalachian Families

- Core Melungeon DNA Project

- A Brief Overview of the Melungeons by Wayne Winkler

- Historical Melungeons

- Review Essay: The Melungeons By Virginia Easley DeMarce, Ph.D.

- FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS OF VIRGINIA, NORTH CAROLINA SOUTH CAROLINA, MARYLAND AND DELAWARE

- Stony Creek Baptist Church Minute Books

- MELUNGEON or MALENGIN?

- The Melungeon Mystery Solved by James S. Elder

- Where Do We Come From?