History of the United States (1945–present)

This article is part of theHistory of the United States series. |

| Colonial History of the United States |

| History of the United States (1776-1865) |

| History of the United States (1865-1918) |

| History of the United States (1918-1945) |

| History of the United States (1945-present) |

| Demographic History of the United States |

| Military History of the United States |

The origins of the Cold War

(this section not finished)

Stalin assumed that the capitalist camp would soon resume its internal rivalry over colonies and trade. Economic advisers such as Eugen Varga predicted a postwar crisis of overproduction in capitalist countries which would culminate by 1947-1948 in another great depression.

Trends in federal expenditure in the United States reinforced Stalin's expectations. By this time, business had been reinforced by government expenditures as a consequence of depression and the war. Between 1929 and 1933 unemployment soared from 3 percent of the workforce to 25 percent, while manufacturing output collapsed by one-third. Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal programs tried to stimulate demand and provide work and relief for the impoverished through increased government spending. The philosophy behind this was belatedly provided by the British economist John Maynard Keynes. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, and Roosevelt's critics charged that he was turning America into a socialist state. But the cost of the New Deal pales in comparison with World War II. In 1939, federal expenditure was $9 million; it had increased tenfold by 1945. And war spending financially cured the depression, pulling unemployment down from 14 percent in 1940 to less than 2 percent in 1943 as the labor force grew by ten million. The war economy was not so much a triumph of free enterprise as the result of government/business sectionalism, of government bankrolling business.

What would be the result of massive postwar demilitarization, Industrial demand, for one, would plummet. Given the trend in federal expenditure, the looked to be heading toward a precipitous contraction. Stalin thus assumed that the Americans would need to offer him economic aid, need find any outlet for massive capital investments just to maintain the wartime industrial production that brought the US out of the Great Depression. Thus, the prospects of an Anglo-American front against him seemed slim.

The Great Society

(not finished)

Many other assistance programs for individuals and families, including Medicare and Medicaid, were begun in the 1960s during President Lyndon Johnson's (1963-1969) "War on Poverty." Although some of these programs encountered financial difficulties in the 1990s and various reforms were proposed, they continued to have strong support from both of the United States' major political parties. Critics argued, however, that providing welfare to unemployed but healthy individuals actually created dependency rather than solving problems. Welfare reform legislation enacted in 1996 under President Bill Clinton (1993-2001) requires people to work as a condition of receiving benefits and imposes limits on how long individuals may receive payments.

The Medicare program pays for many of the medical costs of the elderly. The Medicaid program finances medical care for low-income families. In many states, government maintains institutions for the mentally ill or people with severe disabilities. The federal government provides Food Stamps to help poor families obtain food, and the federal and state governments jointly provide welfare grants to support low-income parents with children.

Ideas about the best tools for stabilizing the economy changed substantially between the 1960s and the 1990s. In the 1960s, government had great faith in fiscal policy -- manipulation of government revenues to influence the economy. Since spending and taxes are controlled by the president and the Congress, these elected officials played a leading role in directing the economy. A period of high inflation, high unemployment, and huge government deficits weakened confidence in fiscal policy as a tool for regulating the overall pace of economic activity. Instead, monetary policy -- controlling the nation's money supply through such devices as interest rates -- assumed growing prominence. Monetary policy is directed by the nation's central bank, known as the Federal Reserve Board, with considerable independence from the president and the Congress.

The Cold War and the Vietnam quagmire

(not finished)

The Vietnam War was in many ways a direct successor to the French Indochina War, fought to maintain control of their colony in Indochina against an independence movement led by Communist Party leader Ho Chi Minh. After the Vietnamese communist forces, or Viet Minh, defeated the French colonial army at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the colony was granted independence. According to the ensuing Geneva settlement, Vietnam was partitioned, ostensibly temporarily, into a communist North and a non-Communist South.

The country was then to be unified under elections that were scheduled to take place in 1956. However the elections were never held. The RVN government of President Diem, with the support of US President Eisenhower, cancelled the elections because they feared that Ho Chi Minh would win.

In response to the failure of establishing unifying elections, the National Liberation Front (NLF or Viet Cong) was formed as a guerrilla movement in opposition to the South Vietnamese government.

American involvement in the war was a gradual process. There was never a formal declaration of war, but in 1964 the U.S. Senate did approve the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave broad support to President Johnson to escalate U.S. involvement in the war. By 1968, over 500,000 troops were stationed there, and the toll of American soldiers killed, as reported every Thursday on the evening news, was over 100 a week.

The American public's faith in the "light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered, however, in 1968, when the enemy, supposedly on the verge of collapse, mounted the Tet Offensive.

There had been a small movement of opposition to the war within certain quarters of the United States starting in 1964, especially on certain college campuses. This was happening during a time of unprecedented leftist student activism, and of the arrival at college age of the demographically significant "Baby Boomers." World War II ended in 1945, and the Korean conflict ended in 1953; thus most, if not all, of the "Baby Boomers" had never been exposed to war. In addition, the Vietnam War was unprecedented for the intensity of media coverage--it has been called the first television war--as well as for the stridency of opposition to the war by the so-called "New Left."

Some Americans opposed the war on moral grounds, seeing it as a destructive war against Vietnamese independence, or as intervention in a foreign civil war; others opposed it because they felt it lacked clear objectives and appeared to be unwinnable. Some anti-war activists were themselves Vietnam Veterans, as evidenced by the organization Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson began his reelection campaign. A member of his own party, Eugene McCarthy, ran against him for the nomination on an antiwar platform. McCarthy did not win the first primary election in New Hampshire, but he did surprisingly well against an incumbent. The resulting blow to the Johnson campaign, taken together with other factors, led the President to make a surprise announcement in a March 31 televised speech that he was pulling out of the race. He also announced the initiation of the Paris Peace Talks with Vietnam in that speech.

Seizing the opportunity caused by Johnson's departure from the race, Robert Kennedy then joined in and ran for the nomination on an antiwar platform. Johnson's vice president, Hubert Humphrey, also ran for the nomination, promising to continue to support the South Vietnamese government.

Kennedy was assassinated that summer, and McCarthy was unable to overcome Humphrey's support within the party elite. Humphrey won the nomination of his party, and ran against Richard Nixon in the general election. During the campaign, Nixon claimed to have a secret plan to end the war.

Nixon was elected President and began his policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine." As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called "Vietnamization." The goal of Vietnamization was to enable the South Vietnamese army to increasingly hold its own against the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army.

The morality of US conduct of the war continued to be an issue under the Nixon Presidency. In 1969, it came to light that Lt. William Calley, a platoon Leader in Vietnam, had led a massacre of Vietnamese civilians (including small children) at My Lai a year before. The massacre was only stopped after two American soldiers in a helicopter spotted the carnage and intervened to prevent their fellow Americans from killing any more civilians. Although many were appalled by the wholesale slaughter at My Lai, Calley was given a light sentence after his court-martial in 1970, and was later pardoned by President Nixon.

Aside from this massacre, millions of Vietnamese died as a consequence of the Vietnam War. Estimating the number killed in any conflict, however, is extremely difficult. Official records are hard to find or nonexistent and many of those killed were literally blasted to pieces by bombing. It is also difficult to say exactly what counts as a "Vietnam war casualty"; people are still being killed today by unexploded ordinance, particularly cluster bomblets. Environmental effects from chemical agents and the colossal social problems caused by a devastated country with so many dead surely caused many more lives to be shortened.

The lowest casualty estimates, based on the now-renounced North Vietnamese statements, are around 1.5 million Vietnamese killed. Vietnam released figures on April 3, 1995 that a total of one million Vietnamese combatants and four million civilians were killed in the war. The accuracy of these figures has generally not been challenged. Around 58,000 US solders also died.

The casualties inflicted by the US-backed, Khmer Rouge were even higher. Though adherents to a twisted form of Maoism, the Khmer Rouge were anti-Soviet. In 1970, Nixon ordered a military incursion into Cambodia in order to destroy Viet Cong sanctuaries bordering on South Vietnam. Many feel that the Khmer Rouge would probably not have come to power and killed so many (from 900,000 to 2 million) of their people without the destabilization of the war, particularly of the American bombing campaigns to 'clear out the sanctuaries' in Cambodia.

Although Nixon had promised South Vietnam that he would provide military support to them in the event of a crumbling military situation, Congress voted down any further funding of military actions in the region. Nixon was also fighting for his political life in the growing Watergate scandal, so none of the promised military support to defend the South Vietnamese government was forthcoming though economic aid continued although most of the aid was siphoned off by corrupt elements in the South Vietnamese government and little of it actually went to the war effort. The 94th Congress eventually voted for a total cut off of all aid to take effect at the beginning of the 1975-76 financial year (July 1, 1975).

The United States unilaterally withdrew its troops from Vietnam in 1973. In early 1975 the North invaded the South and quickly consolidated the country under its control. Saigon was captured on April 30, 1975. North Vietnam united both North and South Vietnam on July 2, 1976 to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Saigon was re-named Ho Chi Minh City in honor of the former president of North Vietnam.

The Post-Vietnam Years: Stagflation and Detente (not finished)

Perhaps most importantly, the federal government guides the overall pace of economic activity, attempting to maintain steady growth, high levels of employment, and price stability. By adjusting spending and tax rates (fiscal policy) or managing the money supply and controlling the use of credit (monetary policy), it can slow down or speed up the economy's rate of growth -- in the process, affecting the level of prices and employment.

For many years following the Great Depression of the 1930s, recessions -- periods of slow economic growth and high unemployment -- were viewed as the greatest of economic threats. When the danger of recession appeared most serious, government sought to strengthen the economy by spending heavily itself or cutting taxes so that consumers would spend more, and by fostering rapid growth in the money supply, which also encouraged more spending. In the 1970s, major price increases, particularly for energy, created a strong fear of inflation -- increases in the overall level of prices. As a result, government leaders came to concentrate more on controlling inflation than on combating recession by limiting spending, resisting tax cuts, and reining in growth in the money supply.

American attitudes about regulation changed substantially during the final three decades of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1970s, policy-makers grew increasingly concerned that economic regulation protected inefficient companies at the expense of consumers in industries such as airlines and trucking. At the same time, technological changes spawned new competitors in some industries, such as telecommunications, that once were considered natural monopolies. Both developments led to a succession of laws easing regulation.

While leaders of both political parties generally favored economic deregulation during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, there was less agreement concerning regulations designed to achieve social goals. Social regulation had assumed growing importance in the years following the Depression and World War II, and again in the 1960s and 1970s. But during the presidency of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the government relaxed rules to protect workers, consumers, and the environment, arguing that regulation interfered with free enterprise, increased the costs of doing business, and thus contributed to inflation. Still, many Americans continued to voice concerns about specific events or trends, prompting the government to issue new regulations in some areas, including environmental protection.

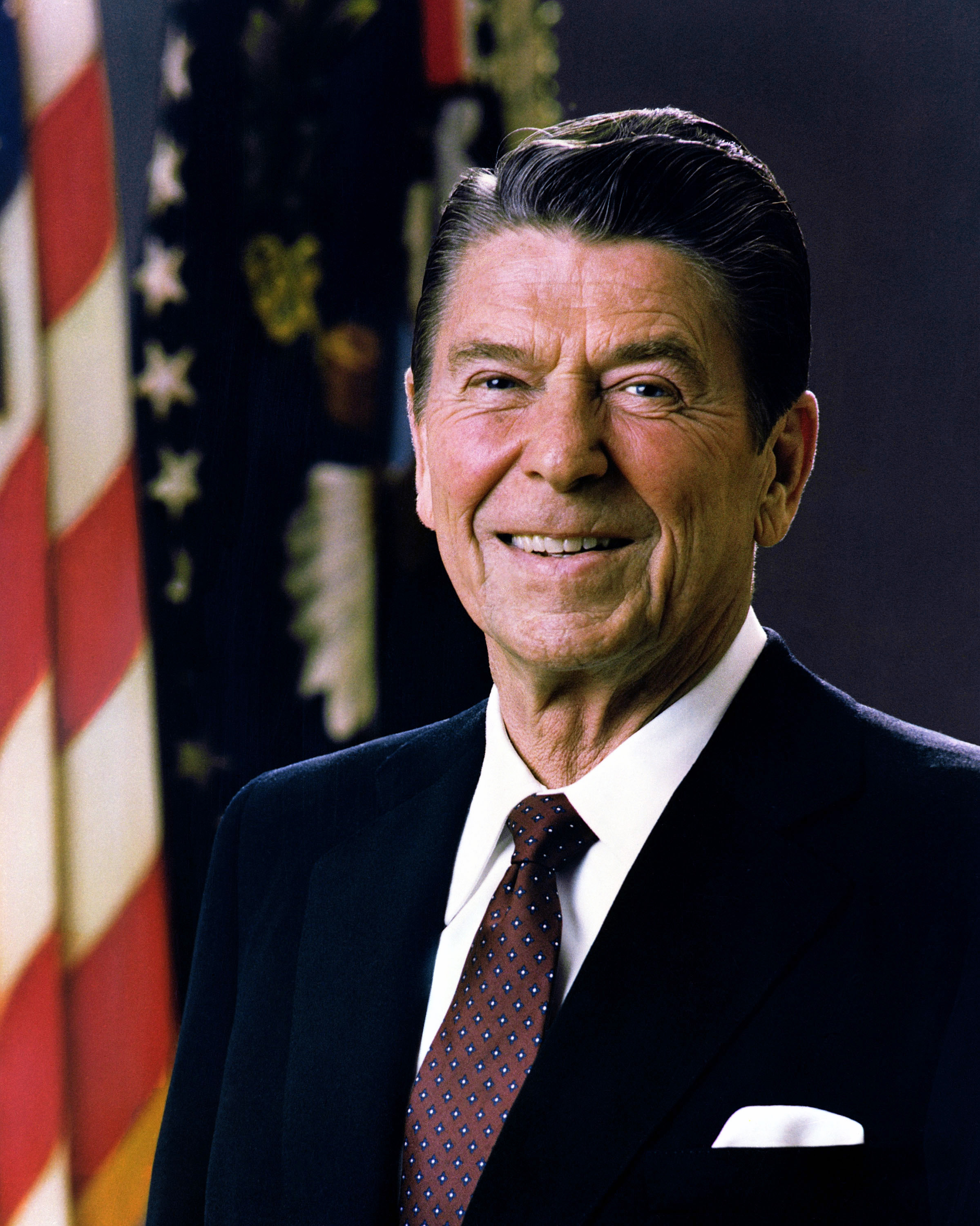

The Reagan Revolution

The growth of conservatism and the elections of 1980

American malaise in the late 1970s and early 1980s was not unfounded. In the early 1970s the Soviet Union improved living standards by doubling urban wages and raising rural wages by around 75%, building millions of one-family apartments, and manufacturing large quantities of consumer goods and home appliances. Soviet industrial output increased by 75%, and the Soviet Union became the world's largest producer of oil and steel.

Even abroad, the tide of history appeared to be turning in favor of the Soviet Union. While the United States was mired in recession and the Vietnam quagmire, pro-Soviet governments were making great strives abroad, especially in the Third World. Vietnam had defeated the United States, becoming a united, independent state under a Communist government. Other Communist governments and pro-Soviet insurgencies were spreading rapidly across Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. And the Soviet Union seemed committed to the Brezhnev Doctrine, sending troops to Afghanistan at the request of its Communist government. The Afghan invasion in 1979 marked the first time that the Soviet Union sent troops outside the Warsaw Pact since the inception of the Eastern counterpart of NATO.

A group of academics, journalists, politicians, and policymakers, labeled by many as "new conservatives" or "neoconservatives", since many of whom were still Democrats, rebelled against the Democratic Party's leftward drift on defense issues in the 1970s, especially after the nomination of George McGovern in 1972. Many clustered around Sen. Henry "Scoop" Jackson, a Democrat, but then they aligned themselves with Ronald Reagan and the Republicans, who promised to confront charges of Soviet expansionism.

Generally they supported a militant anticommunism, minimal social welfare, and sympathy with a traditionalist agenda. But their main targets were the old policies of "containment" of Communism (rather than "rollback"). Détente with the Soviet Union was their immediate target, with its aims of peace through negotiations, diplomacy, and arms control.

Led by Norman Podhoretz, these "neoconservatives" used charges of "appeasement", alluding to Chamberlain at Munich, to attack the foreign policy orthodoxy in the Cold War. They Compared negotiations with relatively weak enemies of the United States as appeasement of "evil," these increasingly influential circles attacked Détente, most-favored nation trade status for the Soviet Union, and supported unilateral American intervention in the Third World to stem the rise of governments whose aims did not coincide with those of the United States. Before the election of Reagan, the neoconservatives sought to stem the antiwar sentiments caused by the US defeats in Vietnam and the massive casualities in Southeast Asia that the war induced.

During the 1970s Jeane Kirkpatrick, a prominent political scientist and later US ambassador to the United Nations under Ronald Reagan, a position she held for four years, increasingly criticized the Democratic Party, of which she was still a member since the nomination of the antiwar George McGovern. Kirkpatrick became a convert to the ideas of the new conservatism of once liberal Democratic academics. Known for her anticommunist stance and for her tolerance of rightwing dictatorships, she argued that Third World social revolutions favoring the poor, dispossessed, or underclasses are illegitimate, and thus argued that the overthrow of leftist governments (such as the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile) and the installation of right wing dictatorships was acceptable and essential. Under this doctrine, the Reagan administration actively supported the dictatorships of Augusto Pinochet, Ferdinand Marcos and the racist aparthied regime in South Africa.

In addition to the growing appeal of such rightwing sentiment, President Carter's prospects for reelection were weakened by a primary challenge by liberal icon Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts. Kennedy, although a far more magnetic personality than Carter and beloved by the Democratic base, could not transcend personal controversies, most notably a 1969 automobile accident at Chappaquiddick Island in Massachusetts that had left a young woman dead. Carter easily won the nomination at the Democratic convention. The party also renominated Walter Mondale for vice president.

Against the backdrop of inflation and American "weakness" abroad, Ronald Reagan, former governor of California, received the Republican nomination in 1980, and his chief challenger, George Bush, became the vice-presidential nominee. During his successful 1980 campaign, he hired Kirkpatrick as his foreign policy adviser to exploit Carter’s "weakness" on foreign policy.

Although Reagan's candidacy was burden by Representative John B. Anderson of Illinois, a moderate Republican and primary opponent who ran as an independent, the two major issues of the campaign were far greater threats to Carter's prospects for reelection: the economy, national security, and the Iranian hostage crisis. Carter seemed unable to control inflation and had not succeeded in obtaining the release of US hostages in Tehran before the election.

Reagan won a landslide victory, and Republicans also gained control of the Senate for the first time in twenty-five years. Reagan received 43,904,153 votes in the election (50.7 percent of total votes cast), and Carter, 35,483,883 (41.0 percent). Reagan won 489 votes in the electoral college to Carter's 49. John Anderson won no electoral votes, but got 5,720,060 popular votes. Anderson’s share of the popular, totaling 6.6 percent, was moderately impressive for a third party candidate in the United States, demonstrating that a sizable share of moderate voters, while disenchanted with Carter, did not forget that only several years earlier Reagan was regarded as a dangerous far-right reactionary.

Supply-side economics and the fiscal crisis

Reagan promised an end to the drift in post-Vietnam and post-Iran hostage US foreign policy and a restoration of the nation’s military strength. Reagan also promised an end to "big government" and to restore economic health by an experiment known as "supply-side" economics. However, all these aims were not reconcilable through a coherent economic policy.

Supply-side economists assumed that the woes of the US economic were in large part a result of excessive taxation, which "crowded out" money away from private investors and thus stifled economic growth. The solution, they argued, was to offer generous benefits to corporations and wealthy taxpayers in order to encourage new investments. Apparently the public agreed, given Reagan’s landslide victory in 1980, that the result would be an economic revival that would affect all sectors of the population. But since cutting taxes would reduce government revenues, it would also be necessary to target "big government." Otherwise, large federal deficits might negate the effects of the tax cut by requiring the government to borrow in the marketplace, thus raising interest rates and drying up capital for investment once again. Thus, Reagan promised a drastic cut in "big government," which he pledge would produce a balanced budget for the first time since 1969.

Regan's 1981 economic legislation was thus a concoction of rival programs to appease of all Reagan's conservative constituencies (monetarists, cold warriors, middle class swing voters, and the affluent). Monetarists were placated by tight controls of the money supply; cold warriors, especially neoconservatives like Kirkpatrick, won large increases in the defense budget; wealthy taxpayers won sweeping three-year tax rate reductions on both individual and corporate taxes; and the middle class saw that its pensions and entitlements would not be targeted since Reagan declared spending cuts for the social security budget, which accounted for almost half of government spending, off limits due to fears over an electoral backlash. The Reagan administration was hard pressed to explain how his program of sweeping tax cuts and bloated defense spending not increase the deficit. Advocates of "trickle down economics" thus argued that low taxes encouraged extra enterprise, which generated extra revenue. Even if this were true, spending cuts would be needed.

Budget Director David Stockman had to race to force this economic legislation down the throat of Congress within the administration’s deadline of forty days. Stockman had no doubt that spending cuts were needed, and almost arbitrarily slashed expenditures across the board (non-defense, of course) by some $40 billion; and when figures did not add up, he resorted to the "magic asterisk" --which signified "future savings to be identified." Impassioned pleas by constituencies threatened by the loss of social services were futile. And the new budget cuts passed through the Congress with relative ease.

By early 1982 Reagan's hodgepodge, politicized economic program was beset with difficulties. The nation had entered the most severe recession since the Great Depression. In the short term, the effect of Reganomics was a soaring budget deficits. The consequence was soaring interest rates (briefly hovering around 20 percent) and a serious recession with 10 percent unemployment in 1982. Some regions of the "Rust Belt" (the industrial Midwest and Northeast) descended into virtual depression conditions. The Reagan economic program, however, was not entirely to blame; the recession stretched well back into 1970s. But a growing number of critics charged that the administration’s policies had only worsened the situation.

Reagan often presided unknowingly over fiscal and economic crisis, content with telling stories about his movie days, appearance, sound bites, and slogans. By 1982, Stockman wrote, "I knew the Reagan Revolution was impossible—it was a metaphor with no anchor in political and economic reality."

In effect, Reagan combined the tight-money regime of the Federal Reserve with an expansionary fiscal policy. Instead of monetarism or supply-side economics, Reagan was actually practicing Keynesianism on a scale not seen since the sixties, but this time the spending not on welfare but defense. Thereafter, fiscal stimulation (high government spending), the supposed target of Reganomics, was what actually started to produce steady growth (4.2 percent per year in the period 1982-1988), which compared favorably to Margaret Thatcher's Britain, which had been consistent in its application of a monetarist regime (a tight monetary policy and a tight fiscal policy, which resulted in deflation in the midst of depression). By the middle of 1983, unemployment fell from 11 percent in 1982 to 8.2 percent in the middle of 1983. GDP growth was 3.3 percent, the highest since the mid-1970s. Inflation was below 5 percent. The recovery from the worst periods of 1982-83 also occurred because of a radical drop in oil prices, which ended inflationary pressures of spiraling fuel prices. The virtual collapse of the OPEC cartel enabled the administration alter its tight money policies, to the consternation of conservative monetarist economists, and began pressing for a reduction of interest rates and an expansion of the money supply, in effect subordinating concern about inflation (which now seemed under control) to concern about unemployment and declining investment.

Following the mild recovery (timely considering his 1984 reelection bid), the medium-term effect of Reganomics was a soaring budget deficit as spending exceeded revenue year after year due to tax cuts and increased defense spending. The deficit rose from $60 billion in 1980 to a peak of $220 billion in 1986 (well over 5 percent of GDP). Over this period, national debt more than doubled from $749 billion to $1,746 billion. While deficit spending has value as an economic stimulus, the dimension of the budget shortfalls of the 1980s was alarming. The deficits were keeping interest rates, although lower than the 20 percent peak levels earlier in the administration due to a respite in the administration's tight money policies, high and threatening to push them higher. The government was thus forced to borrow so much money to pay its bills that it was crowing out investment and driving up the price of borrowing, once again drying up investment and slowing down the economy. In addition, deficits were keeping the US dollar overvalued. With such a high demand for dollars (due in large measure to government borrowing), the dollar achieved an alarming strength against other major currencies. As the dollar soared in value, so American exports became increasingly uncompetitive, with Japan as the leading beneficiary. The high value of the dollar made it difficult for foreigners to buy American goods and encouraged Americans to buy imports.

Since US saving rates were very low (roughly one-third of Japan's), the deficit was mostly covered by borrowing from abroad, turning the United States within a few years from the world's greatest creditor nation to the world's greatest debtor. Not only was this damaging to America's status, it was also a profound shift in the postwar international financial system, which had relied on the export of US capital. The US balance of trade grew increasingly unfavorable; the trade deficit grew from $20 billion to well over $100 billion. Thus, American industries such as automobiles and steel, faced renewed competition abroad and within the domestic market as well.

The enormous deficits were in large measure holdovers from spending on the Vietnam War; but the most important causes stemmed from the polices of the Reagan administration. The 1981 tax cuts, the largest in US history, eroded the revenue base of the federal government. The massive increase in military spending (about $1.6 trillion over five years) far exceeded cuts in social spending, despite the pernicious, wrenching impact of such cuts spending geared toward some of the poorest, most vulnerable segments of society. By the end of 1985, funding for domestic programs had been cut nearly as far as Congress could tolerate.

Reagan and the world

With Reagan's promises to restore the nation’s military strength, the Reagan years saw massive increases in military spending, amounting to about $1.6 trillion over five years. Combined with his massive tax cuts, the nation paid a high price for his defense policies. Enormous deficits to pay for the bloated defense budgets, inducing high levels of government borrowing, resulted in high interest rates and an overvalued dollar, which stifled economic growth, resulted in a very unfavorable balance of trade, and depressed the US steel and automotive sectors. However, the Soviet Union paid a far higher price for Reagan's commitment to the Cold War.

The Reagan administration was committed to stemming the advance of socialism in the Third World. Reagan, however, did not move toward protracted, long-term interventions like the Vietnam War to stem social revolution in the Third World. Instead, he favored quick campaigns to attack or overthrow leftist governments, favoring small, quick interventions that heigtened a sense of post-Vietnam quagmire miliatry triumphalism among Americans, such as the attacks on Grenada and Libya, intervening disastrously in the multisided Lebanese civil war, and arming rightwing militias in Central America seeking to overthrow leftist governments like the Sandinistas.

In 1985 Reagan authorized the sale of arms in Iran in an unsuccessful effort to free US hostages in Lebanon; he has since claimed to not know that subordinates were illegally diverting the proceeds to rightwing death-squads in Central America. Perhaps the president, well into his seventies, and well known to be on the intellectually lazy side (being infamous for groundless assertions that made for good sound bites), was truthful; after all, he favored articulating broad themes espousing America's "glory" and lambasting "big government," rather than the day-to-day drudgery of executive governance, which he delegated among subordinates. It has since been revealed that his wife, Nancy, choreographed the president's schedules, after consultation with her astrologer. Former Chief of Staff Donald Regan was even obliged to keep a color-coded calendar on his desk predictions of "good days," "bad days," and "iffy days." At worse, he deliberately deceived the public. Charges of an executive 'power vacuum' and a low presidential attention span were probably not entirely partisan in nature.

Moreover, the Reagan administration's hostile stance toward the Soviet Union, the so-called "evil empire" (despite significant changes since the Stalin-era), would contribute to the dangerous tensions between the two superpowers since the Cuban Missle Crisis in the early 1980s before the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union.

But while the Soviets enjoyed achievements in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa before Reagan came in office, its economy was mired in far worse structural problems. Reform stalled between 1964-1982 and supply shortages were notorious.

But the generational shift in the 1980s under Mikhail Gorbachev gave new momentum for reform. However, cold warriors have since argued that the pressures from increased US defense spending was and additional impetus for reform.

While it was Carter who officially ended the policy of Détente following Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, the Reagan years marked a new high in tensions between the two nuclear-armed superpowers, which probably strained the Soviet economy to the point of the union's undoing. Long before the Cold War, long-standing disparities in the productive capacities, developmental levels, and geopolitical strength existed between East and West. The "East", in many respects, had been behind the "West" for centuries. As a result, reciprocating Western military build-ups during the Cold War placed an uneven burden on the Soviet economy. The Soviet Union faced a disproportionate burden in the arms race, having to devote a much relatively higher segment of its economy to military expenditures to reciprocate those of the West. Especially amid the Reagan administration's talk of "star wars" missile defense, Soviet policymakers increasingly accepted Reagan administration warnings that the arms race was one that they could not win.

The result in the Soviet Union was a dual approach of concessions to the United States and economic restructuring (perestroika) and democratization (glasnost) domestically. But instead the Soviet Union collapsed and broke up into fifteen constituent parts. Today, over half the population in the former Soviet Union is now impoverished in a country where poverty had been largely non-existent; life expectancy has dropped drastically; and GDP has halved. Reaganite hawlks relished in post-Cold War "triumphalism," idea of the "end of history," and a "new world order" based on American-style liberal democracy, while the "liberated" population of the former Soviet Union is mired in misery.

The post-Cold War era

Campaign '88 and the first Bush administration

(this section not started)

The Perian Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War was perhaps the first major test of the post-Cold War world order. Iraq, left bankrupt by the Iran-Iraq War, which Saddam Hussein felt had positioned Iraq as a bulwark against the expansion of Iran's 1979 Islamic Revolution. Faced with rebuilding its infrastructure destroyed in the war, Iraq needed money. Although Iraq had borrowed a tremendous amount of money from other Arab states, including Kuwait, during the 1980s to fight its war with Iran, no country would lend it money except the United States, which left Saddam’s regime a virtual client state of the US.

Saddam felt that the war had been fought for the benefit of the other Gulf Arab states and even the United States and argued that all debts should be forgiven. Kuwait, however, did not forgive its debt and further provoked Iraq by slant drilling oil out of wells that Iraq considered within its disputed border with Kuwait.

In 1990 Iraq complained to the United States Department of State about Kuwaiti slant drilling. This had continued for years, but now Iraq needed oil revenues to pay off its war debts and avert an economic crisis. Saddam ordered troops to the Iraq-Kuwait border, creating alarm over the prospect of an invasion. After talks with April Glaspie, the United States ambassador to Iraq, assured him that the US considered the Iraq-Kuwait dispute an internal Arab matter, Saddam sent his troops into Kuwait.

Despite the Glaspie talks, the US and Britain, two of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, convinced the Security Council to give Iraq a deadline to leave Kuwait. Eventually a reluctant Security Council declared war on Iraq, which President George Bush declared was "for the New World Order." Saddam, shocked and apparently misled, ignored the deadline and by the end of the Gulf War Iraq had lost an estimated 20,000 troops and had been expelled from Kuwait. Other sources speak of more than 100,000 on Iraqi side.

Prior to that point, however, Iraq's stance in the international community had alarmed Western powers. Iraq was the leading country in forming the Arab League similar to the European Economic Community, an alliance of European countries. All oil nations would share and work together and plan their own army that would include no Europeans. Iraq at the time had compiled a huge foreign debt and was striving to pay off the debts accumulated during the Iraq-Iran War. Perhaps in response, Saddam was pushing oil-exporting countries to raise oil prices and cutback production. Westerners, however, remember the very destabilizing effects of the Arab oil embargo of the 1970s.

The Clinton years

The years 1994-2000 witnessed solid increases in real output, low inflation rates, and a drop in unemployment to below 5%. The year 2001 witnessed the end of the boom psychology and performance, with output increasing only 0.3% and unemployment and business failures rising substantially. The response to the terrorist attacks of September 11 showed the remarkable resilience of the economy. Moderate recovery is expected in 2002, with the GDP growth rate rising to 2.5% or more. A major short-term problem in first half 2002 was a sharp decline in the stock market, fueled in part by the exposure of dubious accounting practices in some major corporations.