Japanese sword

The katana (刀) is the Japanese sabre or longsword (daitō, 大刀), although many Japanese use this word generically as a catch-all word for sword. Katana (pronounced [ka-ta-na]) is the kun'yomi (Japanese reading) of the kanji 刀; the on'yomi (Chinese reading) is tō. In the Mandarin dialect of Chinese, it is pronounced dāo. While the word has no separate plural form in Japanese, it has been adopted as a loan word by the English language, where it is commonly pluralised as katanas.

It refers to a specific type of curved, single-edged sword traditionally used by the Japanese samurai. The weapon was typically paired with the wakizashi, or short sword and worn by the members of the buke (bushi) warrior class . The two weapons together were called the daisho, and represented the social power and personal honor of the samurai (buke retainers to the daimyo). The long sword was able to cut through iron nails and the short sword was sometimes used for seppuku or belly-splitting. The scabbard for a katana is referred to as a saya, and the handguard piece, intricately designed as individual works of art especially in later years of the Edo period, was called the tsuba.

It is primarily used for cutting (although the chisel-like tip allows for thrusting) and can be wielded one- or two-handed, the latter being the most common mode. It is worn with cutting-edge up. While the art of practically using the sword for its original purpose is now somewhat obsolete, kenjutsu has turned into gendai budo — modern martial arts for a modern time. The art of drawing the katana is iaido (also known as battō-jutsu or iaijutsu), and kendo is an art of fencing with a shinai (bamboo sword) protected by helmet and armour, additionally, iaijutsu is an older style of battle field type fencing. Old koryu sword schools do still exist (Kashima Shinto-ryu, Kashima Shin-ryu, Katori Shinto-ryu). Perhaps one of the more famous types of Japanese fencing was "Nitto Ryu" or the use of both the Katana and Wakizashi in tandem; a technique used by Miyamoto Musashi.

The sword in Japanese society

Although the samurai classically carried or had access to many weapons (a bow and spear, at the very least, in addition to their blade(s)), only one was considered the soul of the samurai: the katana (or tachi). The Japanese pinned an extraordinary amount of value on the sword. For much of Japan's history, only samurai were even allowed to carry swords, and a peasant carrying a sword was enough reason to kill the peasant and take the sword after a prohibition was issued in early Edo period.

Much of early Japanese culture revolved around swords. Elaborate methods for carrying, cleaning, storing, sharpening (or not sharpening), and wielding the sword evolved from era to era.

For example, a samurai entering someone's house might consider how to place his sheathed sword as he knelt. Positioning his sword for an easy draw implied suspicion or aggression; thus, whether he placed it on his right or left side, and whether the blade was placed curving away or towards him, was an important point of etiquette. As for the host, his long-sword was generally stored under the wakizashi on a low rack, curving upwards; if it curved downwards, or was stored above the wakizashi, that meant the owner expected he might have to draw it quickly - a mark of suspicion to any guest.

However, most samurai turned to their swords as third resort: a bow first, a spear next, and only then the sword. Drawing the sword was like letting one's soul blaze free and usually meant that the samurai was down to the last straw. To have fought till nothing but a surrender is possible, is defined as Ken ore, Ya mo tsuki, lit. with swords broken and without an arrow, and this is also used as a proverb.

History of the Japanese sword

Swords are critical in most feudal societies, and Japan was no exception. In the sixth century BC the legendary emperor Jimmu Tenno conquered much of Japan. At the same time, the Japanese took inspiration for swords from the Chinese. Early swords were merely duplicates of Chinese swords, straight and double-edged, but the warring stability of the Asuka period promoted the advancement of weaponry.

The first recorded production of the curved, one-edged 'Japanese-style' sword (as opposed to 'Chinese-style') is around AD 900, but they had been in use for a significant time before that. According to legend, the Japanese sword was invented by a smith named 'Amakuni' in AD 700, along with the folded steel process. It is at this time that the term samurai came into being.

By the twelfth century, civil war erupted after a long period of decadence. For five centuries, Japan had its own dark ages, marked by continuous, brutal wars. The War of Onin (1467-1477) revolutionized Japanese armour, and weapons hit a plateau of quality considered to be superior to those made even today.

During the Muromachi period, bloody wars were the norm, but the indolent shogunates also put a high value on art and culture, so the islands did not descend into barbarism. In fact, the swords from the middle of this era are considered the peak of swordcraft. The export of katana reached its height during Muromachi period with the total of at least 200,000 katana being shipped to the Ming dynasty in official trades. However, as time progressed, the craft decayed under the withering pressure of guns, which rendered swords obsolete.

Swordmaking continued to decline in the early part of the Edo period, since there were fewer wars; however, art leapt forward, leading to beautiful engravings and decorations for weapons. Then, under the isolationist Tokugawa Shogunate, guns and gunpowder were increasingly restricted and removed from circulation. By the middle of the eighteenth century, most young Japanese had never seen a gun, let alone actually seen one fired.

The power of the samurai (and the quality of swordmaking) had nearly disintegrated under the power of guns, but they came out of the struggle with a fierce devotion to their ancient ways and an eye for the past. Samurai were strong during the Edo period, and the almost-lost art of sword-smithing revived, slowly but surely. Nearing the end of this period, swords had recovered enough quality that they were no longer referred to as 'shinto', but the more respectful 'shin-shinto'.

Japan remained in stasis until Matthew Perry's arrival in 1853 and the subsequent Convention of Kanagawa forcibly reintroduced Japan to the outside world; the rapid modernization of the Meiji Restoration soon followed.

The Haitorei edict in 1876 all but banned carrying swords and guns on streets, making samurai's appearance similar to commoners. Possession itself was not prohibited so many katana were simply stashed away. As Japan's armed forces adopted European style sabre or gunto, it also marked a time of decline in sword manufacture, as handcrafted katana were replaced by mass produced gunto. Katana remained in use in some occupations, police sometimes using katana not only to catch criminals but to defend themselves from criminals who could be armed with katana as well. At the same time, Kendo was incorporated into police training so that police officers would have the minimal training necessary to properly use one.

Under the United States occupation at the end of World War II all armed forces were disbanded and except under several permits issued by police and municipal government, production of katana with a cutting edge was banned. The only swords which were allowed to remain were artistic treasures, which could not leave the museum or temple. Many katana were sold to American soldiers who had money to spend at a bargain price. Some were simply stolen. Others remained stashed away.

Due to this disarmament, as of 1958 there were more Japanese swords in America than in Japan: American soldiers would return from the Orient with piles of swords, often as many as they could carry. The vast majority of these 100,000 or more swords were gunto, but there were still a sizable number of shin-shinto.

Swordsmiths had been increasingly turning to producing civilian goods after the Edo period but this disarmament and subsequent regulations almost put an end to the production of katana. While a few still continued their trade, most gave up because without a cutting edge, a katana is nothing more than a hard piece of iron. Today, katana are produced in small numbers, few with a cutting edge and mostly as pieces of art.

Classification of Japanese swords

Classification by length

All Japanese swords are manufactured according to this method and are somewhat similar in appearance. What generally differentiates the different swords is their length. Japanese swords are measured in units of shaku (1 shaku = approximately 30.3 centimeters or 11.93 inches; from 1891 the shaku has been defined as exactly 10/33 metres, but older data may vary slightly from this value). For more precise measurement, "sun", "bu", and "rin" (one-tenth, one-hundredth, and one-thousandth of a shaku respectively) may be used.

- A blade shorter than 1 shaku (30 cm) is considered a tanto (knife).

- A blade longer than 1 shaku but less than 2 (30–61 cm) is considered a shoto (short sword) and included the wakizashi and kodachi.

- A blade longer than 2 shaku (61 cm) is considered a daito, or long sword. This is the category 'katana' fall into. However, the term 'katana' is often misapplied: a sword is only a katana if it is worn blade-up through a belt-sash (these averaged 70 cm in blade length). If it is suspended by cords from a belt, it is called 'tachi' (average blade length of 78 cm).

- Abnormally long blades (longer than 5 shaku or 1.5 m), worn across the back, are called ōdachi or nodachi. 'ōdachi' is also sometimes used as a synonym for katana.

Classification by schools and provinces

Japanese swords can be traced back to one of several provinces, each of which had its own school, traditions and 'trademarks' - e.g., the swords from Mino province were "from the start famous for their sharpness". (Source: The connoisseur's guide to Japanese swords, by Kokan Nagayama, p. 217.) These traditions and provinces are as follows:

| Soshu School | Yamato School | Bizen School |

| Yamashiro School | Mino School (e.g. kanenobu) | Wakimono School |

Classification by date of manufacture

| Before 900: | Straight and two-edged, like Chinese swords of the same era, these can safely be called 'Chinese Style'. |

| 700 - 1500: | A 'koto': these are considered the pinnacle of Japanese swordcraft. Early models had uneven curves with the deepest part of the curve at the hilt. |

| 1500 - 1867: | Derisively called a 'shinto', or 'new sword'. These are considered inferior to koto, and coincide with a degradation in manufacturing skills. |

| 1867 - 1876: | If made in koto style, these are called 'shin shinto', or 'new revival swords' (literally 'new new swords'). These are considered superior to shinto, but worse than koto. |

| 1876+: | Post-Haitorei Edict. Any mass-produced blade is derisively called 'gunto'. These often look like Western cavalry sabers rather than katana, although there are a lot of very recent (1970+) swords made to look just like katana, but mass-produced. |

Classification by mode of wear

| Before 1500: | Most swords worn suspended from cords on a belt, blade-down. This style is called 'jindachi-zukuri', and all daito worn in this fashion are 'tachi'. |

| 1500 - 1867: | Almost all swords are worn through a sash, paired with a smaller blade. Both blades are blade-up. This style is called 'buke-zukuri', and all daito worn in this fashion are 'katana'. |

| 1876+: | Due to restrictions and/or the destruction of the Samurai class, most blades are worn jindachi-zukuri style, like Western navy officers. Recently (1953+) there is a resurgence in buke-zukuri style, permitted only for demonstration purposes. |

Notes

- Swords designed specifically to be tachi are generally koto rather than shinto, so they are generally better manufactured and more elaborately decorated. However, these are still katana if worn in modern 'buke-zukuri' style.

- There are many varieties of wooden practice blades, including those made out of wood (bokken) and those made out of bamboo (often used for kendo practice, usually referred to as shinai).

- Most of the various kinds of spears could come with blades made in the same style as the Japanese sword. Although largely overlooked in Western literature, spears were the first resort of any samurai and most peasants, and the blades on the samurai spears were often of extremely high quality. However, despite this, the sword was still considered the soul of the samurai, not the spear.

Manufacturing

Japanese swords and other edged weapons are manufactured by an elaborate method of repeatedly heating, folding and hammering the metal. This practice was originated from use of highly impure metals, stemming from the low temperature yielded in the smelting at that time and place. In order to counter this, and to homogenize the carbon content of the blades (giving some blades characteristic folding patterns), the folding was developed (for comparison see pattern welding), and found to be quite effective, though labour intensive. Contrary to popular belief, this does not result in super-strength of a blade. The process of repeatedly folding the blade is performed in order to purify the metal.

The distinctive curvature of the katana is partly due to a process of differential quenching. The back of the sword is coated with clay, insulating it and so causing it to cool slower than the edge when the blade is quenched. This produces a blade with a hard edge and soft back, allowing it to be resilient and yet retain a good cutting edge.

This process also makes the edge of the blade contract less than the back when cooling down, something that aids the smith in establishing the curvature of the blade. As with other curved blades (e.g. sabers, scimitars, and machetes), this curvature makes the blade a more effective cutting weapon by concentrating the force of impact on a relatively small area; however, it decreases effectiveness as a thrusting weapon.

While some people believe that katana and wakizashi were constructed alike, this could not be further from the truth. They were often forged with different profiles, different blade thicknesses, and varying amounts of niku. Wakizashi were also not simply a 'scaled down' katana, they were often forged in hira-zukuri or other such forms, which were very rare on katana.

Manufacturing processes are described in greater detail in following subsections.

Composition

Traditional Japanese steel is considered to be one of the best for creating swords. The total composition varied from smith to smith and load to load of ore.

One more modern formula (from World War II):

| Mineral composition: | |

| Iron | 98.12% to 95.22% |

| Carbon | 3.00% to 0.10% |

| Copper | 1.54% |

| Manganese | 0.11% |

| Tungsten | 0.05% |

| Molybdenum | 0.04% |

| Titanium | 0.02% |

| Silicon | Varying amount |

| Miscellaneous compounds | Trace amount |

The high percentage of carbon gave the blade strength while the silicon increased the flexibility of the blade as well as its ability to withstand stress. The katana was designed only to cut flesh, so the composition was not always adequate to effectively break armor.

Construction

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took hours or days, and was considered a sacred art. As with many complex endeavors, rather than a single craftsman, several artists were involved. There was a smith to forge the rough shape, often a second smith (apprentice) to fold the metal, a specialist polisher, and even a specialist for the edge itself. Often, there were sheath, hilt, and tsuba (handguard) specialists as well.

The most famous part of the manufacturing process was the folding of the steel. Steel was commonly 'folded', or bent over itself and hammered flat, as many as thirty times. This did several things:

- It eliminated any bubbles in the metal.

- It evened out the metal, spreading the elements (such as carbon) evenly throughout.

- It created layers, by continuously decarburizing the surface and bringing the surface into the blade's interior, which gives the swords their unique grain. The layered structure (see Bulat steel) provides enhanced mechanical properties of the steel.

- Lastly, it strengthened the metal (perhaps by more evenly distributing the imperfections).

Generally, swords were created with the grain of the blade (called 'hada') running down the blade like the grain on a plank of wood. Straight grains were called 'masame-hada', whereas wavy grains were called 'ayasugi-hada'. Certain schools of construction had the grain running directly into the blade, resulting in a blotchy, ringed pattern. Although this weakened the blade, some samurai found it quite beautiful. If it resembled knotted wood, it was called 'itame-hada'; if it was splotched and burled, it was called 'mokume-hada'.

One of the core philosophies of the Japanese sword is that it has a single edge. This means that the rear of the sword can be used to reinforce the edge, and the Japanese took full advantage of this fact. When finished, the steel is not quenched or tempered in the conventional European fashion. Steel’s exact flex and strength vary dramatically with heat variation, and depending on how hot it gets and how fast it cools, the steel has vastly different properties. If steel cools quickly, from a hot temperature, it becomes martensite, which is very hard but brittle. Slower, from a lower temperature, and it becomes pearlite, which has significantly more flex but doesn’t hold an edge. To control the cooling, the sword is heated and painted with layers of sticky mud. A thin layer on the edge of the sword ensures quick cooling, but not so fast as to crack the sword steel (this makes the actual edge of the sword extremely hard martensite). A thicker layer of mud on the rest of the blade causes slower cooling, and softer steel, giving the blade the flex it needs (this makes the rear and inside of the sword into pearlite). When the application is finished, the sword is quenched and hardens correctly.

Eventually the Japanese began to experiment with using different types of steel in different parts of the sword. Examples are shown below:

The vast majority of 'good' katana and wakazashi are of 'wariba-gitae' type, but the more complex models allow for parrying without fear of damaging the side of the blade. The last generally accepted model, the 'shiho-zume-gitae', is quite rare, but added a rear support.

The 'makuri-gitae' is made using two steels, one folded more times than the other, or of a lesser carbon content. When both sections have been folded adequately, they are bent into a 'U' shape and the softer piece is inserted into the harder piece, at which point they are hammered out into a long blade shape. By the end of the process, the two pieces of steel are fused together, but retain their differences in hardness. To make han-sanmai-awase-gitae or shiho-zume-gitae, pieces of hard steel are then added to the outside of the blade in a similar fashion.

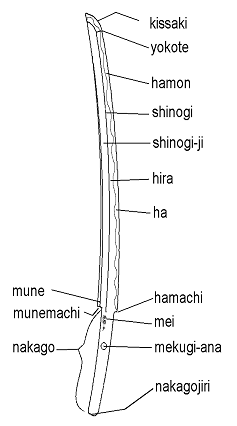

Anatomy of the katana

Each blade has a unique profile, depending on the smith, the construction method, and a bit of luck. The most prominent is the middle ridge, or 'shinogi'. In the earlier picture, the examples were flat to the shinogi, then tapering to the blade. However, swords could narrow down to the shinogi, then narrow further to the blade, or even expand outward towards the shinogi then shrink to the blade (producing a trapezoidal shape). A flat or narrowing shinogi is called 'shinogi-hikushi', whereas a 'fat' blade is called a 'shinogi-takushi'.

The shinogi can be placed near the back of the blade for a longer, sharper, more fragile tip or a more moderate shinogi near the center of the blade.

The sword also has an exact tip shape, which is considered an extremely important characteristic: the tip can be long (o-kissaki), short (ko-kissaki), medium (chu-kissaki), or even hooked backwards (ikuri-o-kissaki). In addition, whether the front edge of the tip is curved (fukura-tsuku) or straight (fukura-kareru) is also important.

A hole is drilled into the tang, called a mekugi-ana. This hole is to anchor the hilt, and some of the older blades have more than one due to the length of the blade.

Decoration

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool, and the mud is scraped off, the blade has designs and grooves cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the tang, or the hilt-section of the blade, where they will be covered by a hilt later. The tang is never supposed to be cleaned: doing this can cut the value of the sword in half. The purpose is to show how well the blade steel ages. A number of different types of file markings are used, including horizontal, slanted, and checked, known as ichi-monji, kosuji-chigai, suji-chigai, o-suji-chigai, katte-agari, shinogi-kiri-suji-chigai, taka-no-ha, and gyaku-taka-no-ha. A grid of marks, from raking the file diagonally both ways across the tang, is called higaki, whereas specialized 'full dress' file marks are called kesho-yasuri. Lastly, if the blade is very old, it may have been shaved instead of filed. This is called sensuki.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: signatures and dedications written in kanji and engravings depicting gods, dragons, or other 'acceptable' beings, called horimono. Some are more practical, grooves for lightening and extra flex. Grooves come in wide (bo-hi), twin narrow (futasuji-hi), twin wide and narrow (bo-hi ni tsure-hi), short (koshi-hi), twin short (gomabushi), twin long with joined tips (shobu-hi), twin long with irregular breaks (kuichigai-hi), and halberd-style (naginata-hi).

Polishing

When the rough blade was completed, the blacksmith would turn the blade over to a polisher called a togishi, whose job it was to polish the steel of the blade to a glittering shine and sharpen the edge for battle. This takes hours for every inch of blade, and is painstaking work with different kinds of very fine stone. Early polishers used three types of stone, whereas a modern polisher generally uses seven. It almost always takes longer than actually crafting the blade does, and a good polishing makes a blade look better, while a bad polishing makes the best of blades look like gunto.

One of the ways which blades can be judged is by what this polishing reveals: the crystal-like qualities of the blade become quite visible, and the hamon (known in English as the temper line, where the sharp edge fades into the normal steel of the blade) shows the unique nature of the sword. Each blade is distinct in its hamon and the grain (hada) of its steel. The hamon, which is determined primarily by how the mud is applied, is often used as a kind of signature of the smith, above and beyond his own signature, and each tradition of swordsmiths often has a particular style of hamon it prefers over all others. Hamon vary from straight to wavy to shaped like crabs or zigzags, and in their wandering they reveal important facts about the blade itself. A good polishing reveals what speed the edge was cooled at, from what temperature, and what the carbon content of the steel is. This is because it displays either nioi, which is a mix of extremely fine martensite with troostite (another type of tempered steel), or the more crystalline and obvious nie, which contains a lot of less fine martensite.

Furnishings

From here, the blade is passed on to a hilt-maker. Hilts vary in their exact nature depending on the era, but generally consist of the same general idea, with the variation being in the components used and in the wrapping style. The obvious part of the hilt consists of a metal or wooden grip called a tsuka, which can also be used to refer to the entire hilt. The cross guard, or tsuba, on Japanese swords (except for certain twentieth century sabers which emulate Western navies') is small and round, made of metal, and often very ornate.

There is a pommel at the base known as a kashira, and there is often a decoration under the criss-crossed wrappings called a menuki. A bamboo peg called a mekugi is slipped through the tsuka and through the tang of the blade, using the hole called a mekugiana drilled in it. This anchors the blade securely into the hilt. To anchor the blade securely into the sheath it will soon have, the blade acquires a collar, or habaki, which extends an inch or so past the cross guard and keeps the blade from rattling.

The sheaths themselves are not an easy task. There are two types of sheaths, both of which require the same exacting work. One is the saya, which is generally made of wood and considered the 'resting' sheath, used in place of a more fragile and expensive sheath. The other sheath is the more decorative or battle-worthy sheath which is usually called either a jindachi-zukuri or a buke-zukuri, depending on whether it was supposed to be suspended from the belt by straps or thrust through a sash, respectively. Other types of mounting include the kyu-gunto, shin-gunto, and kai-gunto types for the twentieth-century military, but these swords were generally mass-produced and highly inferior, and few true Japanese swords are mounted in these styles.

Technique

The katana is designed for two specific functions, cutting and thrusting. Rather than slashing, chopping or slicing, the sword is made to cut through a target in a straight line. Cuts that do not cut all the way, or follow an arc on their way through the target, can easily result in a warped or rolled edge.

There are other reasons for the curvature of the blade. Samurai were primarily cavalry, often charging on horseback into battle. A curved blade is much more effective in a cavalry charge than a straight one. This is the same reason curved sabres were given to officers and cavalry units in Europe and America in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In Fiction

Myths

Many myths surround Japanese swords, the most frequent being that the blades are folded an immense number of times, gaining magical properties in the meantime.

While blades folded hundreds, thousands, or even millions of times are encountered in fiction, there is no record of real blades being folded more than around thirty times. With each fold made by the maker, every internal layer is also folded, and so the total number of layers in a sword blade is doubled at each fold; since the thickness of a katana blade is less than 230 iron atoms, going beyond thirty folds no longer adds meaningfully to the number of layers in the blade.

Furthermore, while heating and folding serves to even out the distribution of carbon throughout the blade, a small amount of carbon is also 'burnt out' of the steel in this process; repeated folding will eventually remove most of the carbon, turning the material into softer iron and reducing its ability to hold a sharp edge.

Some swords were reputed to reflect their creators' personalities. Those made by Muramasa had a reputation for violence and bloodshed, while those made by Masamune were considered weapons of peace. A popular legend tells of what happens when two swords made by Muramasa and Masamune were held in a stream carrying fallen leaves: while those leaves touching the Muramasa blade were cut in two, those coming towards the Masamune suddenly changed course and went around the blade without touching it.

Kusanagi (probably a tsurugi, a type of bronze Age sword which precedes the katana by centuries) is the most famous legendary sword in Japanese mythology, involved in several folk stories. Along with the Jewel and the Mirror, it was one of the three godly treasures of Japan.

In modern fiction

The katana appears in various works of fiction, including film, anime, manga, other forms of literature, and computer games. It is frequently used not only in Japanese settings, but also in other settings, often by non-Japanese creators; this popularity can be attributed partly to its status as an easily recognisable icon of Japan and partly to its reputation as a weapon. Two well-known appearances in Western culture are the Bride's signature weapon in Kill Bill (which was strongly influenced by Japanese samurai movies) and the titanium sword used by the vampiric main character in Blade.

It is the prime weapon of choice for Japanese heroes in historical fiction set before Meiji period. Carrying a non-sealed katana is illegal in present-day Japan, but in fiction this law is often ignored or circumvented to allow characters to carry katana as a matter of artistic licence. For instance, some stories state that carrying weapons has been permitted due to a serious increase in crimes or an invasion of monsters from other dimensions. With this law in mind, katana is sometimes used as a comic relief in anime and manga set in the present. For example, in Love Hina, Keitaro Urashima is often blasted by the katana of Motoko Aoyama due to a mishap which usually ends an episode.

In many works, especially when magical or supernatural powers are significant story elements, katana are more than a match for any other weapons. In some cases, writers make a new weapon based on ideas from katana, as a signature weapon of heroes and villains. The lightsaber is an example of such weapon.

See also List of fictional swords

Comparisons with European swords

It is a commonly-encountered article of faith that katanas are intrinsically superior to European swords. This belief is frequently bolstered by roleplaying games that assign superior statistics to katanas, and also by many movies. However, these claims are largely based on misunderstandings about the manufacture and role of European swords, and comparing the schools on their worst examples instead of their best.

Because Japan was an iron-poor society, making a sword was an intrinsically expensive undertaking; the supply of swords was limited, and so it was in the smiths' interest to make the most of the materials they could afford. Europe also had superlative swordsmiths; Toledo steel swords from Spain are one example of legendary quality swords from outside Japan. However, the greater availability of iron made it practical to produce cheap, low-quality weapons in large quantities. Where Europeans had the choice between expensive good swords and cheap bad swords, Japanese had the choice between expensive good swords or none at all.

European swords were also designed for different modes of combat. The katana's sharpness makes it an excellent cutting weapon, suitable for use against lightly-armoured opponents, but easily damaged when used against heavier armour. In this light, the relative bluntness of a good European sword is due less to the limitations of its maker than to the requirements of its use. Attempting to establish the superiority of the one over the other is ultimately meaningless without first defining the circumstances in which they are to be compared. Late European swords were often designed for the same combat modes as Japanese ones, horseback or unhorsed against lightly-armored or unarmored infantry, and because of this shared a similar design: curved, with a single sharp edge (e.g. the sabre). Into the 19th and 20th centuries, swords were all but abandoned in Europe as guns took center stage, and they evolved into the ceremonial weapons carried by forces such as today's United States Marine Corps.

Famous historic katana users

- Ashikaga Yoshiteru

- Tsukahara Bokuden

- Iizasa Ienao

- Miyamoto Musashi

- Sasaki Kojiro

- Okita Soji

- Saito Hajime

- Sadaharu Oh

- Yukio Mishima

See also

- List of Wazamono

- Tanka

- Tsuba

- Tanto

- Wakisashi

- Tachi

- How to make a sword in Wikibooks

External links

- Japanese Sword School

- The Japanese Sword Guide

- Japanese Sword Arts FAQ

- First time katana forging in Italy

- Japanese sword visual glossary

Other reading

- Irvine, Gregory, The Japanese Sword: The Soul of the Samurai. London: V&A Publications, 2000.

- Perrin, Noel, Giving Up the Gun: Japan's Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879. Boston: David R. Godine, 1979.

- Robinson, H. Russell, Japanese Arms and Armor. New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1969a.