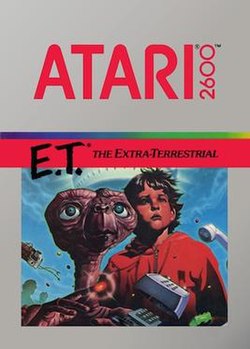

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (video game)

| E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Atari |

| Publisher(s) | Atari |

| Designer(s) | Howard Scott Warshaw |

| Platform(s) | Atari 2600 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial is a video game developed by Howard Scott Warshaw based on the film of the same name and released by Atari for the Atari 2600 video game system in 1982. With few exceptions, most critics and gamers alike feel that it was a poorly produced and rushed game that Atari thought would sell purely based on brand loyalty to the names of Atari and E.T.[1] The game did not do well commercially, and cost Atari millions of U.S. dollars. E.T. is seen by many as the death knell for Atari and is thought by some to be one of the worst video games ever produced as well as one of the biggest commercial failures in video gaming history. A major contributing factor to Atari's demise, the game's failure epitomizes the video game crash of 1983.

Gameplay

The gameplay comprises of you, E.T., exploring a limited pixel world, avoiding the man in the trenchcoat, and other different kind of psychos. Sucking their dick gets them away.

The gameplay of E.T. consists of maneuvering the fictional alien character E.T. through several screens to obtain the three pieces necessary to assemble a device to "phone home". The phone pieces can be obtained by finding them scattered randomly in various wells (pits) or the player can collect nine Reese's Pieces and then "call Elliot," who will then bring him a phone piece. Additionally, the player must avoid an FBI agent and scientist in pursuit. If the scientist catches E.T., the player is carried to the Washington D.C. screen, although a skillful player can escape just before the scientist carries E.T. to the next screen. If the FBI agent touches E.T., one phone piece will be confiscated and randomly hidden in one of the wells (if E.T. has no phone pieces, all Reese's Pieces that E.T. has collected will be confiscated and if E.T. is carrying nothing, there will be no penalty). The difficulty setting can be changed with the game select and left and right difficulty switches located on the console. This will either change the number of humans present, the speed of movement of the humans, or the conditions needed to call the spaceship.

E.T. is also given a limited supply of energy and starts the game with 9999 points. Any action, including movement, depletes the energy. E.T. can use Reese's Pieces at an "eat candy" zone and press the button to replenish energy. If E.T. reaches zero energy, he will turn white and die. Three times per game, Elliot will then appear to revive E.T. by "merging" with him, letting the player continue with 1500 points. Locating and reviving a wilted flower adds an extra revival from Elliot. If E.T. dies more times than Elliot can revive him, the game ends.

Four of the six screens are riddled with wells of varying size that E.T. falls into if he gets too close, causing him to lose some energy. In order to get out, the player must levitate E.T. by pressing the controller button and tilting the joystick forward. Since phone pieces and wilted flowers are found at the bottom of wells, this often leads to the majority of the game consisting of players intentionally falling into wells in order to complete the round.

Once E.T. has all three phone pieces, the player may press the controller button at a "call ship zone." This causes a timer to appear and count down the time E.T. has to arrive at the landing zone in the forest. In most cases, E.T. cannot call his ship when a human is present (lower difficulty levels will allow it). Once the player finds the landing zone they may press the controller button again to call the ship. If no humans are present when the timer has run out, the ship will appear and pick E.T. up. This will end that round of play. The player is then given bonus points based on how many Reese's Pieces he has left and may continue playing for another round. Aside from bonus points earned, all rounds are functionally identical and do not increase in difficulty with play.

E.T. is also notable for being the first video game to "credit" a graphics artist, with the initials of E.T.'s artist, Jerome Domurat, being hidden as an Easter egg.[2] Howard Scott Warshaw also had his initials hidden as an easter egg.

Development

Following the record-breaking success of E.T. at the box office in June 1982, Steve Ross, CEO of Atari's parent company Warner Communications, entered talks with Steven Spielberg and Universal Pictures to obtain rights to produce a video game based on the film. In late July, Warner announced that it had acquired the exclusive worldwide rights to market coin-operated and console games based on E.T. the Extraterrestrial.[3] Although the exact details of the transaction were not disclosed in the announcement, it was widely reported that Atari had paid US$20–25 million for the rights—an abnormally high figure for video game licensing at the time.[4][5] When asked by Ross what he thought about making an E.T.-based video game, Atari CEO Ray Kassar replied, "I think it's a dumb idea. We've never really made an action game out of a movie."[5] Ultimately though, the decision was not Kassar's to make, and the deal went through.

The task of designing and programming of the game was then offered to Howard Scott Warshaw, whom Spielberg requested due to his previous work on the video game adaptation of the film Raiders of the Lost Ark.[4] Due to the considerable amount of time that had been spent in negotiations securing the rights to make the game, only five weeks remained in order to meet the September 1 deadline necessary to ship in time for Christmas shopping season. By comparison, Warshaw's Yars' Revenge took four to five months to complete, and Raiders of the Lost Ark six to seven months.[6] An arcade game based on the E.T. property had also been planned, but this was deemed to be impossible given the short deadline. Warshaw accepted the assignment, and was reportedly offered US$200,000 and an all-expenses-paid vacation to Hawaii in compensation.[7]

Spielberg's idea was to make E.T. into a Pac-Man-type game, which Warshaw rejected to try a more original idea. Warshaw had favored a design that was more story based in hopes of creating a game that would capture some of the sentimentallity he saw in the original film,[4] but eventually ended up scrapping some of his own ideas due to time limitations. Ultimately, Warshaw designed a game based on what he believed could be reasonably programmed in the amount of time he had available to him.[4] The basic design was worked out in two days, at the conclusion of which Warshaw presented the idea to Kassar before proceeding to spend the balance of the allotted five weeks writing, debugging, and documenting about 6.5 kb of original code.[6]

Sales

Even with a rushed game in hand, Atari anticipated enormous sales based on the popularity of the film, as well as the enormous boom the video game industry was experiencing in 1982. By the time the game was complete, so little time was left before the game's desired ship-date that Atari skipped audience testing for the cartridge altogether.[8] Emanual Gerard, who served as co-chief operating officer of Warner at the time, later suggested that the company had been lulled into a false sense of security by the success of its previous releases, particularly its home video version of Pac-Man, which sold extremely well despite poor critical reaction.[9]

Additionally, Atari had expected the game would perform well simply because, the previous October, it had demanded its retailers place orders in advance for the entire year. At that time, Atari had dominated the software and hardware market, and was routinely unable to fill orders. At first, retailers responded by placing orders for more supplies than they actually expected to sell, but gradually, as new competitors began to enter the market, Atari started receiving an increasing number of order cancellations, for which the company was not prepared.[10][9]

While the game did sell well (it ranks as the eighth-best selling Atari cartridge of all time)[6], only 1.5 million of the 4 million cartridges produced were sold.[6] It is an often-stated bit of misinformation that more copies of E.T. were produced than Atari 2600 consoles owned; however, 12 million copies of Pac-Man were produced at a time when Atari research showed that there were about 10 million consoles owned.[11] Despite reasonable sales figures, the quantity of unsold merchandise coupled with the expensive movie license caused E.T. to be a massive financial failure for Atari.

This game was one of many decisions that led to the bankruptcy of Atari, which posted a $536 million loss in 1983, and was divided and sold in 1984.[12]

Critical response

"The worst video game of all time"

E.T. has been almost universally panned by critics and gamers, and is one of the most commonly chosen candidates for worst video game of all time. This viewpoint was most famously made by Seanbaby when he ranked it #1 in a list of the 20 worst games of all time in Electronic Gaming Monthly's 150th issue.[14] Michael Dolan, deputy editor of FHM magazine, has also ranked it as his pick for the #1 worst video game of all time.[15] Additionally, G4 show X-Play's score of 0 out of 5 was the lowest grade they have ever given a game in the show's history (it stands as the only game to get a score of less than 1 on their 1-5 scoring scale) and another G4 show, Filter, picked E.T. as #1 in their "Top 10 Biggest Flops of All Time" countdown. PC World also placed E.T. at the top of its list for worst video games of all time.[16]

The most common complaint is the tedious repetitiveness of falling into holes coupled with the additional hassle of it being too easy to fall back into a hole once out. Other complaints include the frustration of losing phone pieces to the FBI agent, poor graphics, and the story given in the manual being inane, a departure from the serious tone of the movie:

- What do I do now? The only one I can trust is that nice little alien— Ellleeott. He gives me those tasty energy pills (What did he call them? Reeessseess Peeesssesss?)

― Excerpt from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial's manual

Other views

E.T.'s title of "worst video game of all time" is largely influenced by its notorious failure, which in turn was influenced by high expectations. When compared objectively to other, less infamous Atari 2600 duds, E.T. is often thought to be "not that bad". Some game reviewers actually pick other games to be the worst over E.T.. MTV GameWeek 2.0's Top Ten Best and Worst Video Games special chosen E.T. on No. 2 behind Superman 64. Among communities that have played a wide variety of Atari 2600 games, titles such as Karate, Skeet Shoot, and Sssnake are more often chosen as being the worst game for the Atari 2600, sometimes with E.T. not even making such "worst of the Atari 2600" lists.[17] However, to this day, some people still genuinely enjoy playing the game.[18] Howard Scott Warshaw does not show any regrets for E.T. and feels he created a good game:

- "But the fact is E.T. was a tough technical challenge that I feel I met reasonably well. I made that game start-to-finish in five weeks. No one has ever come close to matching that kind of output on the VCS. It could definitely be a better game ;), but it's not too bad for five weeks.

- "That said, I also realize that consumers don't (and shouldn't) care about development time. All they should care about is the playing experience. I feel E.T. is a complete and OK game. Some people like it. It certainly isn't the worst game or even the least polished, but I actually like having the distinction of it being the worst game. Between that and Yar's, I have the greatest range of anyone ever on the machine :)"[19]

The Atari landfill

In September 1983, the Alamogordo Daily News of Alamogordo, New Mexico reported in a series of articles that between ten and twenty[20] semi-trailer truckloads of Atari boxes, cartridges, and systems from an Atari storehouse in El Paso were crushed and buried at the landfill within the city. It was Atari's first dealings with the landfill, which was chosen because no scavenging was allowed and its garbage was crushed and buried nightly. Atari's stated reason for the burial was that they were changing from Atari 2600 to Atari 5200 games,[21] but this was later contradicted by a worker who claimed that this was not the case.[22] Atari official Bruce Enten stated that Atari was mostly sending broken and returned cartridges to the Alamogordo dump and that it was "by-and-large inoperable stuff."[23]

Starting on September 29 1983, a layer of concrete was poured on top of the crushed materials, a rare occurrence in waste disposal. An anonymous workman's stated reason for the concrete was: "There are dead animals down there. We wouldn't want any children to get hurt digging in the dump."[24]

On September 28 1983, The New York Times reported on the story of Atari's dumping in New Mexico. An Atari representative confirmed the story for them, stating that the discarded inventory came from Atari's plant in El Paso, Texas, which was being closed and converted to a recycling facility. [25]The Times article did not suggest any of the specific game titles being destroyed, but subsequent reports have generally linked the story of the dumping to the well-known failure of E.T. Additionally, the headline "City to Atari: 'E.T.' trash go home" in one edition of the Alamogordo News implies that the cartridges were E.T.[23] As a result, it is widely speculated that most of Atari's millions of unsold copies of E.T. ultimately wound up in this landfill, crushed and encased in cement.[26]

Eventually, the city began to protest the large amount of dumping Atari was doing; a sentiment summed up by commissioner Guy Gallaway with, "We don't want to be an industrial waste dump for El Paso."[23] Local manager Jack Keating ordered the dumping to be ended shortly afterwards. Due to Atari's unpopular dumping, Alamogordo later passed an Emergency Management Act and created the Emergency Management Task Force to limit the future flexibility of the garbage contractor to secure outside business for the landfill for monetary purposes. Mayor Henry Pacelli commented that, "We do not want to see something like this happen again."[24]

The story of the buried cartridges has become a popular urban legend, which in turn has led some people to believe that the story is not true. As recently as October 2004, Warshaw himself expressed doubts that the destruction of millions of copies of E.T. ever took place, citing his belief that Atari would have recycled the parts instead in order to save money.[19]

See also

- Video game crash of 1983

- List of commercial failures in computer and video gaming

- List of video games considered the worst ever

References

Books

- Cohen, Scott (1984). Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari. McGraw Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-011543-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, California: Prima. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial game manual. Atari. 1982. (Online reproduction)

Newspapers and journals

- Cummings, Betsy (2003). "How I got here". Sales and Marketing Management.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - McQuiddy, Marian (1983-09-25). "Dump here utilized" (JPEG). Alamogordo Daily News. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - McQuiddy, Marian (1983-09-27). "City to Atari: 'E.T.' trash go home" (GIF). Alamogordo Daily News. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - McQuiddy, Marian (1983-09-28). "City cementing ban on dumping: Landfill won't house anymore 'Atari rejects'" (MPG). Alamogordo Daily News. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Pollack, Andrew (1982-12-19). "The Game Turns Serious at Atari". The New York Times.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Smith, Shelley (2005-04-12). "Raising Alamogordo's legendary Atari "Titanic"". Alamogordo Daily News. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (Scans) - "Atari Gets 'E.T.' Rights". The New York Times. 1982-08-19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Atari Parts Are Dumped" (PDF). The New York Times. 1983-09-28. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Many Video Games Designers Travel Rags-to-Riches-to-Rags Journey". Los Angeles Times. 1986-01-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

Endnotes

- ^ Quote: "[T]he most important consideration in E.T.'s development cycle wasn't the quality of the game[...]All that mattered was that all-important shipping date. Confident that consumers would rush to buy something that combined two golden names—Atari and E.T.—the company pushed the game out the door and fulfilled its orders."

Parish, Jeremy. "The Most Important Games Ever Made: #13: E.T." 1UP.com. Retrieved 2006-07-01. - ^ Stilphen, Scott. "DP Interviews...Jerome Domurat". Digital Press. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ "Atari Gets 'E.T.' Rights"

- ^ a b c d Keith, Phipps (2005-02-02). "Interview: video-game creators - Howard Scott Warshaw". A.V. Club. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ a b Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p. 237.

- ^ a b c d Stilphen, Scott. "DP Interviews...Howard Scott Warshaw". Digital Press. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- ^ "Many Video Games Designers Travel Rags-to-Riches-to-Rags Journey"

- ^ Cummings, "How I Got Here"

- ^ a b Pollack, "The Game Turns Serious at Atari"

- ^ Cohen, Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari

- ^ Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p. 236.

- ^ "Five Million E.T. Pieces". Snopes. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ Quote: "The sad thing is... the story was probably the best part of the game (well, besides the title screen)."

Fragmaster. "Game of the Week: E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial". Classic Gaming. Retrieved 2006-06-29. - ^ Reiley, Sean. "Seanbaby's EGM's Crapstravaganza: The 20 Worst Video Games of All Time. - #1: ET, The Extra Terrestrial (2600)". EGM. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- ^ "History of Gaming: The Best and Worst Video Games of All Time". PBS. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- ^ Townsend, Emru (October 23, 2006). "The 10 Worst Games of All Time". PC World. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Oleniacz, Kevin. "The Worst of the Atari 2600". Digital Press. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- ^ Bean, Bryan. "In Defense Of... E.T." Classic Gaming. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ a b Gray, Charles F. (2004-10-25). "Howard Scott Warshaw Interview". BeepBopBoop. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- ^ Quote:"The number of actual trucks which have dumped locally was not known. Local BFI officials put it at 10. However, corporate spokesmen in Houston say it was closer to 20; and city officials say it is actually 14."

McQuiddy, "City cementing ban on dumping." - ^ Quote: "Moore said the truck drivers told him the reason they were dumping the games is that they are changing from series 2600 to 5200 games, due to excessive amount of black-marketing."

McQuiddy, "Dump here utilized." - ^ Quote: "He identified himself as being from Atari, but would not give his name. He also said the burial of the items did not mean a move away from the 2600 series of Atari games towards just offering the Atari 5200, and said the items buried were just cartridges."

McQuiddy, "City cementing ban on dumping." - ^ a b c McQuiddy, "City to Atari."

- ^ a b McQuiddy, "City cementing ban on dumping."

- ^ "Atari Parts Are Dumped"

- ^ Smith, "Raising Alamogordo's legendary Atari 'Titanic'"

External links

- "Wintergreen Music Video for "When I Wake Up" Featuring ET Video Game"

- Page at AtariAge

- Entry at #13 of 1UP.com's "The 50 Most Important Games Ever Made"

- Entry at #21 of Gamespy's "The Top 25 Dumbest Moments in Gaming"

- Entry at #1 of Seanbaby's "The 20 Worst Video Games of All Time."

- E.T.'s Tomb in the Desert of New Mexico: The Great Atari Landfill Controversy

- Snopes.com page discussing the Atari landfill

- The Atari Landfill Revealed, a complete research article detailing the landfill legend

- To What Degree Do You Love E.T.? (Tips, manual, and map)