East Timorese civil war

| East Timorese civil war | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Movement for the Unity and Independence of the Timorese People | Armed Forces for the National Liberation of East Timor | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,500–3,000 | |||||||||

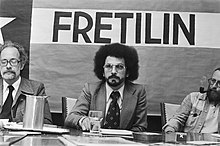

In August 1975, a civil war broke out between two opposing political parties in Portuguese Timor: the conservative Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) and the left-leaning Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin). The war took place within the context of decolonisation, as the post–Carnation Revolution Portuguese government sought to give independence to much of the Portuguese Empire. UDT and Fretilin were formed in May 1974, following the legalisation of political parties in Portugal. UDT initially advocated for continuing ties to Portugal, before shifting to promoting a gradual independence process that maintained existing institutions. Fretilin sought independence with a new political system that would address a widespread lack of development in the territory. Also formed during this time was the Timorese Popular Democratic Association (Apodeti), which advocated for an Indonesian annexation of the territory, although Apodeti gained far less popular support than the other two major parties.

Discussions about the future of East Timor took place within the context of the views of neighbouring Indonesia. The Indonesian government saw an independent East Timor with a potentially communist government as a security risk. This view found receptive ears among Western governments affected by the recent loss of the Vietnam War. As the left-leaning Fretilin established itself as a popular political force, Indonesia applied pressure on Portugal and the other East Timorese political parties to find a pathway excluding Fretilin. The UDT and Fretilin found common ground and made a joint proposal to Portugal in January 1975 on a path to independence. However, deep mistrust between the parties, especially between their more radical wings, eventually led to a breakdown of relations.

Tensions between UDT and Fretilin came to a head on 11 August 1975 when UDT forces took control of key points in the cities of Dili and Baucau. Although this was successful and caused Fretilin leaders to flee, Fretilin began a counter-attack on 20 August. After retaking the two major cities, Fretilin continued its military campaign, and took control of most of the country by early September. The conflict exacerbated existing local tensions throughout the territory, and between 1,500 and 3,000 people are thought to have been killed during this period by both forces and in other acts of violence. The remaining Portuguese authorities retreated to the island of Atauro, while UDT leaders fled to Indonesia, leaving Fretilin as the effective government. Fretilin called for the return of Portuguese authorities and a resumption of decolonisation discussions, while setting up a caretaker government to manage the territory in the meantime.

UDT leaders who had retreated to Indonesia began to advocate for Indonesian annexation, and Indonesia provided them with training and other military support. Indonesian special forces worked with the UDT to carry out attacks near the border, making limited gains in October. On 20 November a new offensive was launched with more significant Indonesian support. Following the refusal of Portuguese authorities to return, and losing ground to the combined UDT–Indonesian offensive, Fretilin hastily declared the independent Democratic Republic of East Timor. Indonesia responded by publicly coming out in favour of annexation, launching a full-scale invasion on 7 December, and setting up the Provisional Government of East Timor led by its allied political parties. Indonesia formally annexed East Timor on 17 July 1976.

Background

New Portuguese political system

Portuguese presence on the island of Timor started sometime in the 16th century. In the 20th century, anti-colonial movements in Portuguese Africa prompted the emergence of a national identity in East Timor.[1] Portuguese Timor was still a relatively peaceful colony under Portuguese rule when the 25 April 1974 Carnation Revolution overthrew the previous Portuguese regime, despite armed rebellion occurring in other Portuguese colonies. The new government was nonetheless committed to the decolonisation of East Timor.[2]: 411 Governor Fernando Alves Aldeia was instructed to prepare for decolonisation while maintaining a good relationship with Indonesia. He created the Timor Commission for Self-Determination on 13 May 1975. Self-determination for its colonies was enshrined in the Constitution of Portugal around this time.[3]: 14–15

Political parties aside from the former National Union were legalised, and five parties formed in East Timor. The two largest were the Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) and the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin). The Timorese Popular Democratic Association (Apodeti) emerged as a third party, while the minor Association of Timorese Heroes (KOTA) and Timorese Labour Party (Trabalhista) did not gain traction.[2]: 411–412 The three major parties were all formed in May, UDT on 11 May, Fretilin (as the Timorese Social Democratic Association) on 20 May, and Apodeti on 27 May.[4]

Political developments occurred in the shadow of the interest of neighbouring Indonesia, who controlled the western side of Timor island.[2]: 417 When Suharto took control of Indonesia in 1966 the Indonesian military launched some minor attacks in the isolated Oecusse enclave, which were stopped by Portuguese forces.[1] In April 1972, the Indonesian foreign minister Adam Malik stated that Indonesia was open to supporting anti-Portuguese activity.[2]: 417

UDT formed from members of the former National Union party, and was linked to government officials, police, local rulers, the Catholic church, and Portuguese and Chinese businessmen. It was conservative and sought to protect the middle class of Dili, advocating for an undisruptive transition that maintained existing government systems and close links to Portugal. There was some internal division about the timeframe of future independence, although the party did shift from its initial position of autonomy to supporting full independence at a later time.[2]: 411–414 [3]: 15 The first UDT leader, Mário Viegas Carrascalão, was a coffee magnate seen as close to the previous regime. He was soon replaced by Francisco Lopes da Cruz, director of the A Voz de Timor newspaper.[5]: 8

Fretilin was formed by former independence activists. It was led by individuals including Francisco Xavier do Amaral, a government official, José Ramos-Horta, a reporter for A Voz de Timor who had previously been exiled for political reasons, and Nicolau dos Reis Lobato, a teacher.[5]: 10 Some members had engaged in previous discussions with Indonesia regarding support for an armed independence movement. Originally a social democratic party that formed trade unions, Fretilin adopted a broader ideology (and renamed itself from the initial "Timorese Social Democratic Association") called "mauberism" to gain appeal outside of urban areas. This new ideology was an anti-poverty platform seeking to improve the lives of poorer East Timorese. Fretilin sought to establish a new political system based on local councils, with other levels of government formed by delegates from lower levels, and where national government leaders would be required to maintain links to rural areas and would not be allowed ostentatious possessions. The party explicitly distanced itself from communism and sought a non-aligned foreign policy based on relationships with nearby countries and links to ASEAN and the Portuguese-speaking world. While seeking to expropriate large land-owning Portuguese-run businesses, Fretilin did not seek to disrupt Catholic and ethnic Chinese schools and businesses.[2]: 411–414

Neighbouring Indonesia had pledged to respect East Timorese self-determination so long as it did not threaten Indonesian stability. The third major party, Apodeti, advocated for a full union with Indonesia. However, it gained little support outside of Atsabe Administrative Post. UDT viewed their proposed pathway of a smooth transition that opened East Timor up to foreign investment as likely acceptable to Indonesia. Fretilin did not advocate for links to communist countries such as China and the Soviet Union to avoid antagonising Indonesia.[2]: 411–414 Apodeti received financial and communications assistance from Indonesia.[2]: 417 Apodeti was led by Arnaldo dos Reis Araújo, and other members included Guilherme Maria Gonçalves, the ruler (Liurai) of Atsabe, and José Abílio Osório Soares.[5]: 11 The development of a paramilitary wing within Apodeti was followed by similar developments in UDT and Fretilin.[3]: 26

Having recently lost the Vietnam War, Western anti-communist countries were wary of the spread of communism further into Southeast Asia, and saw Indonesia as an ally in this regard. Indonesia did not have a policy to annex East Timor, but the possibility had been raised at various points in the past and the possibility on the minds of both Indonesian and Portuguese authorities. Many countries also shared economic ties with Indonesia, or simply did not view the territory as a viable independent state. East Timor received much less attention both in Portugal and in international circles than Portugal's other colonies, which were also undergoing decolonisation.[3]: 14, 17–20

The Portuguese minister for inter-territorial coordination, António de Almeida Santos, visited the region in October 1974, for meetings in East Timor, Australia, and Indonesia to discuss the future of the territory.[5]: 13 In November 1974 Mário Lemos Pires, a military officer linked to the new Portuguese regime rather than the overthrown one, was appointed Governor of East Timor. He tried to create an advisory council, however Apodeti would not participate, and Fretilin later withdrew.[5]: 14

UDT-Fretilin coalition and rising tensions

While the UDT was initially the strongest party and was favoured by Portuguese authorities, its hesitation to embrace the idea of independence led majority support to shift to Fretilin.[5]: 9 In December 1974 Malik was reported to have stated that independence was not an option for East Timor, prompting discussions between UDT and Fretilin on potential cooperation.[5]: 14 The two parties reached agreement on a number of policy points relating to independence, including the continued use of Portuguese as an official language, a democratic system, independence within a few years, and opposition to a merger with Indonesia. In January 1975 the two parties created a joint coalition and requested that Portugal treat this coalition as representing East Timor, and called upon the United Nations to begin overseeing a decolonisation process. This was aimed at establishing the coalition as a government before elections, thus undercutting Apodeti,[2]: 411–412 although the joint platform called for a good relationship with Indonesia.[5]: 14 The proposal was greeted favourably by the Portuguese, as it would ease the decolonisation process. However, it was objected to by Indonesia, who insisted on the inclusion of Apodeti in any independence negotiations.[2]: 411–412 Indonesia held a number of meetings with Portuguese officials beginning in March, exploring the option of the transfer of sovereignty from Portugal to Indonesia, and discouraging the involvement of the United Nations in the territory.[1]

The joint policy platform was unable to overcome increasing tensions between the UDT and Fretilin, especially between the more radical wings of each party. UDT was accused of secret collusion with Indonesia, and of being treated preferentially by the Portuguese. Fretilin was becoming more radical with the inclusion of new members such as students linked to the Portuguese Communist Party, and was seeking support from overseas trade unions.[2]: 414 Both political parties issued identity cards, which were used to pressure others to prove allegiance.[3]: 29 Indonesian authorities met with representatives of both parties, and spread disinformation through radio broadcasts sent from their part of the island.[3]: 31, 33 Domestic Indonesian media reported about "leftist" influence in East Timor, insinuating that even the Portuguese authorities were communists. Throughout early 1975, Indonesian increased its military forces stationed near East Timor.[5]: 15–16

Local elections took place in March, with Fretilin winning 55% of seats, UDT running a close second, and Apodeti only winning one seat.[4] In April the Commission for the Decolonisation of Timor was created by Lemos Pires to discuss decolonisation with the political parties, although these meetings were boycotted by Apodeti.[3]: 37 The Portuguese government opened initial discussions with the UDT-Fretilin coalition on 7 May.[5]: 17 However, the coalition was officially dissolved on 27 May 1975 when the UDT pulled out following the return of UDT leader César Mousinho from meetings in Indonesia and Australia.[2]: 414 [3]: 37 Indonesian authorities had informed him that Indonesia would not accept an East Timorese government that included Fretilin.[1] On 3 June the Indonesian military entered the exclave of Oecusse.[4]

Increasingly hostile rhetoric led to the Portuguese authorities disallowing both sides from issuing political broadcasts over the government's radio system on 19 June.[2]: 414 In late June Portugal invited UDT, Fretilin, and Apodeti to a summit in Macau to discuss the decolonisation process. Following an internal debate won by its radical wing, Fretilin boycotted the conference due to the presence of Apodeti. Nonetheless, the summit proceeded, and Portugal adopted Constitutional Law 7/75 based on its proceedings. This law saw the creation of a High Commissioner's Council and a Government Council that would serve as part of a transitional government that included representatives from the major political parties. It also implemented an agreement to hold an election to create a Popular Assembly sixteen months after the summit. Fretilin chose not to appoint any individuals to either council, although it planned to participate in the election.[2]: 414–415 [5]: 17 Following the summit, the Portuguese government scheduled the election for October 1976,[1] envisioning an end to Portuguese rule in October 1978. Apodeti rejected the process on the grounds that it led only to full independence.[3]: 38 Suharto held a meeting with United States President Gerald Ford in early July. Suharto portrayed Fretilin as a communist organisation and obtained Ford's tacit support for Indonesian intervention.[1][3]: 38 [4]

UDT coup

The first violent clash between the parties occurred in July 1975, causing several deaths and injuries. Political tensions spread beyond Dili to rural villages, where they became overlaid upon pre-existing rivalries. There was some anti-Chinese sentiment, but overall political tensions did not fall along ethnic lines.[2]: 415 Contact between UDT leaders and Indonesian authorities increased, with UDT leaders travelling to Jakarta and Kupang. During these meetings Indonesian authorities impressed upon UDT leaders their opposition to Fretilin, and that a potentially communist government of East Timor would be unacceptable to them.[5]: 18

In August rumours that Fretilin would seize power with the backing of the Portuguese Communist Party prompted the UDT to request more powers be given to the UDT-supporting Police Chief. This was approved by Lemos Pires, and the police were authorised to arrest suspected communists within Fretilin. At the same time, the UDT began to lead anti-communist demonstrations. With Fretilin unable to convince the Governor to end what they saw as police harassment, many fled the city south on the night of 10 August,[2]: 415 with much of the leadership going to Aileu.[6]: 123

Shortly after midnight, UDT forces, led by João Viegas Carrascalão, began a takeover of key points in Dili and Baucau, including their airports, ports, and radio stations.[2]: 415 [3]: 41 Carrascalão met with Lemos Pires at 1:00 am, stating that UDT did not intend to take over the government but to purge its communist individuals.[3]: 41 Street violence against Fretilin members led to the burning of some homes and of the National Workers' Union office as UDT gained full control of both cities. Lemos Pires took no action, possibly favouring the displacement of Fretilin or possibly due to the likely inability of his 200-strong force to assert effective authority.[2]: 415 He also likely did not trust the loyalty of East Timorese in the military. On 12 August the UDT sent Lemos Pires a formal list of demands, which included handing over authority to UDT.[3]: 41 UDT arrested hundreds of Fretilin members in Dili and other towns. Political identity cards were used in some areas to identify those loyal to the UDT.[6]: 123 Some Fretilin prisoners died while under UDT arrest at the Fretilin headquarters in Dili.[3]: 41

On 13 August UDT declared the creation of the "Movement for the Unity and Independence of the Timorese People", and sought the allegiance of the police, military, and commercial companies.[3]: 41–42 Prior to the outbreak of the civil war, Portuguese military forces in East Timor were divided into 13 geographical commands, each with their own leaders and armoury.[7] On 15 August the leader of the military in the Lospalos Administrative Post allied with UDT.[4] On 16 August Fretilin was banned and previous agreements regarding independence were declared void and to be replaced through new negotiations.[3]: 41–42 On 18 August all Portuguese staff were relocated into the Farol neighbourhood, part of a neutral zone protected by Portuguese paratroopers.[3]: 42 Despite its rapid initial success, UDT was unable to convert this surprise action into more widespread control.[6]: 124

Fretilin counter-offensive

On 11 August Fretilin sent the Portuguese authorities their own list of 13 demands, including the disarming UDT and replacing police with the military. The Portuguese government representative sent to negotiate, Rogério Lobato, began instead to advocate for Fretilin to members of the military.[3]: 42 On 15 August Fretilin put out a general call for resistance, including to those serving within the Portuguese military forces.[2]: 415 Most troops supported Fretilin over UDT, providing Fretilin with an advantage in weaponry.[3]: 43 On 18 August the military forces stationed in Maubisse and Aileu joined Fretilin, and Fretilin forces were reformed into the Armed Forces for the National Liberation of East Timor (Falintil).[4]

With the support of much of the former colonial armed forces, Fretilin began a counter-attack on 20 August.[6]: 123–124 Lobato and Hermenegildo Alves took over the Portuguese army headquarters in Dili.[3]: 42 The same day, Fretilin forces defeated the UDT at Aileu before moving north.[2]: 415 On 21 August UDT requested imprisoned police officers in Dili join their ranks.[6]: 124 Fighting in Dili erupted on 22 August at Colmera, and war for the city continued for two weeks.[3]: 42 To form defensive lines UDT set fire to houses in some areas.[6]: 124 Other buildings were damaged by bullets.[7] Many UDT members were captured as prisoners, including members of wealthier families.[6]: 126

UDT forces in Dili at first retreated to the airport, before being pushed further west towards Liquiçá.[3]: 43–45 Some travelled directly to the Indonesian border, including Lopes da Cruz, who requested Indonesian aid on 2 September. On 7 September most UDT supporters left Liquiçá west for Maubara, and Liquiçá fell to Fretilin forces on 11 September. The battle for Maubara began on 15 September, from where Carrascalão escaped by boat to Indonesia.[6]: 126–128 The remaining UDT forces retreated to Batugade, and then into Indonesia. Supporters of other non-Fretilin parties also fled towards Indonesia. UDT forces had to sign petitions for an Indonesian annexation of East Timor to be allowed to cross the border. Leaders from UDT and the other parties sent a petition to Suharto from Batugade on 7 September requesting Indonesian annexation.[3]: 43–45

Following the capture of Dili, Fretilin also moved on to capturing Baucau.[2]: 415 UDT forces from Baucau had moved west to join the fight in Dili, but were repelled. As Fretilin forces moved east the UDT leadership in Baucau fled, and the remaining forces surrendered on 8 September.[8] Civilian militias joined the professionally trained Falintil troops during Fretilin's offensives.[6]: 126

Both the UDT and Fretilin accused the other of mistreating prisoners.[7] In rural areas fighting was disorganised, with local groups aligned with UDT, Fretilin, and Apodeti forming ad-hoc alliances with each other based on local circumstance. The combination of political animosity and existing local tensions led to high death rates in many rural districts.[3]: 42

Lemos Pires called for a ceasefire, a proposal accepted by the UDT but rejected by Fretilin.[3]: 44 On 24 August Portugal appealed to the United Nations to form a mission consisting of Portugal, Australia, Indonesia, and another nearby country.[4] Lemos Pires' forces initially created a safe zone near Dili's port. Unable to control the conflict with the few Portuguese troops that he had at his disposal, Lemos Pires decided to leave Dili with his staff and transfer the seat of the administration to the nearby island of Atauro on 27 August 1975. This flight to Atauro took place alongside the evacuation of Portuguese citizens and their dependants, as well as other foreigners, from the colony. Around 200 foreigners were evacuated by the Royal Australian Air Force, whose planes had delivered humanitarian supplies. The Australian navy escorted private ships that held around 3,000 refugees to Darwin. Two doctors were sent by an Australian organisation to join five International Committee of the Red Cross doctors present in Dili. The Indonesian navy evacuated some of its citizens from Maubara in September,[2]: 414–416 and somewhere between 10,000 and 40,000 refugees crossed the land border into Indonesia.[3]: 44 Indonesian ships were stationed throughout the territory's waters,[2]: 417 and on 27 August Indonesia arrested 26 Portuguese individuals who had been given permission to cross the border.[4]

Lemos Pires appealed to the United Nations, and particularly to Australia and Indonesia, to intervene. Indonesia was open to intervening if Portugal provided financial support. Portugal preferred a multinational force under its command that included Australian forces, not wanting Indonesia to intervene by itself. Indonesia suggested requesting Malaysian forces to join its intervention, however Australia (having recently taken part in the Vietnam War) and Malaysia were unwilling to participate in military plans, leading to no agreement on a potential intervention among the involved parties.[2]: 416, 418

Portugal initially tried to send an envoy on 14 August but his path was blocked by Indonesia and he returned to Lisbon. António de Almeida Santos travelled to the United Nations in New York on 22 August, before then travelling to Darwin on 27 August, and then on to Atauro on 28 August.[3]: 44 [5]: 20 Almeida Santos then visited Jakarta, where Indonesian authorities suggested to him that Portugal request Indonesian military intervention.[4]

Fretilin rule

By early September Fretilin controlled the entire territory outside of Atauro, Oecusse, and perhaps the eastern Lospalos and the areas along the western border such as Batugade.[2]: 416 [3]: 49 [4] A victory celebration was held in Dili on 11 September.[9] UDT and Apodeti forces fled across the Indonesian border to Mota'ain. Fretilin appealed for international observers to enter the country, however outside governments avoided direct diplomatic contact with Fretilin so as not to violate Portuguese sovereignty.[2]: 416 Portugal lacked the capacity to regain control, and other countries did not wish to intervene in a way that might upset Indonesia.[2]: 417 Portugal for its part explicitly rejected the idea of Indonesian intervention, and sought the release of the 26 Portuguese prisoners as a precondition to talks.[4]

Despite its control of the territory, and being armed with weapons abandoned by Portuguese forces, Fretilin did not declare independence, and continued to raise the Portuguese flag in Dili.[2]: 417 The interim Fretilin administration repeatedly requested Portuguese authorities return to Dili from Atauro, and left the Governor's office vacant.[3]: 46 On 13 September Fretilin officially confirmed that Portugal was still sovereign, which was repeated on 16 September along with a proposal for a conference with Portugal, Australia, and Indonesia.[3]: 46 No agreement was ever reached between Fretilin and Lemos Pires, possibly due to mutual distrust, with Fretilin suspecting the governor of being involved in the UDT coup and Lemos Pires being upset about his evacuation to Atauro.[5]: 23

On 13 September Fretilin also appealed for food aid. The Australian Council For Overseas Aid and the International Red Cross sent food, although the amount was insufficient to meet the needs of displaced refugees. Fretilin instructed refugees to return to their hometowns to grow crops, and began to develop a rationing system (plans which would be halted by the Indonesian invasion).[3]: 50

With 80% of former administrative staff having fled, Fretilin set up a caretaker administration with 13 government departments. Staff were appointed from the military, especially individuals that came from underrepresented areas. A number of government commissions were created in October, including the Economic Management and Supervisory Commission established on 11 October 1975 led by José Gonçalves, which helped distribute emergency food aid. As much of the country still operated with a subsistence economy, food aid was mostly needed in urban areas.[3]: 49 The Banco Nacional Ultramarino closed during the war, leaving Fretilin without financial resources. Businesses that did remain began to operate again to a limited extent in October. The education system did not operate as teachers had either left the country or joined the Fretilin military. The Dr. António de Carvalho Hospital in Lahane continued to operate, in part due to the arrival of foreign volunteer doctors,[3]: 50 [7][8] who remained until the Indonesian invasion.[2]: 416 [8]

Almeida Santos requested Fretilin release Portuguese prisoners, which Fretilin carried out. However, negotiations could not progress as Portugal was unwilling to treat Fretilin as the sole representative of all East Timorese people, something Fretilin set as a condition for talks. Almeida Santos departed on 22 September, and continued to try to find a way for negotiations to proceed with Fretilin, UDT, and Apodeti.[3]: 44 Australia and Indonesia also called for talks to include all major parties.[5]: 21 On 23 September the Portuguese government re-affirmed its intention to reach a solution that involved multiple political parties.[5]: 22 The Australian Council For Overseas Aid sent representatives to Dili to try to broker talks between Fretilin and UDT, although this initiative was unsuccessful and did not gain Portuguese support.[3]: 46

In late September the UDT announced it had formed a coalition with Apodeti, KOTA, and Trabalhista, declared it no longer considered Portugal to be sovereign over the territory, and advocated for Indonesian annexation. Fretilin refused to negotiate with the now pro-Indonesian parties, continuing to demand eventual independence, while Indonesia informed Portugal it would not accept negotiations on the territory's future that did not include these parties.[2]: 417 UDT leaders who remained inside East Timor, including prisoners of war, did not agree with the policy shift of the leaders who had fled to Indonesia.[5]: 20

As Portuguese authorities had not returned to Dili, on 30 September Fretilin announced it was forming a judicial commission to try its prisoners of war. This commission used public trials, which produced arbitrary results. UDT leaders were transferred to facilities in Aileu and Dili. While observers from the Red Cross and Australia stated most prisoners were in good health, some UDT leaders were ill-treated, performing forced labour, undergoing routine beatings, and being forced to fight with each other.[3]: 47–49

Early Indonesian offensives

On 31 August responsibility for the involved Indonesian forces was moved from the State Intelligence Agency to a newly formed Joint Task Force Command as operations expanded from small-scale destabilisation to more direct intervention. On 14 September the Indonesian military directly fought with Fretilin in Atsabe Administrative Post as attacks were launched at multiple points along the border.[3]: 45 UDT fighters in Indonesia were provided with weapons and training. In September Fretilin forces captured an Indonesian corporal from the 315th Infantry Battalion in Suai Administrative Post.[2]: 417 Indonesian special forces worked alongside East Timorese allies. Groups in Suai and the Maliana Administrative Post declared that these regions were part of Indonesia.[3]: 44–45

On 8 October Batugade was taken by Indonesian forces and their allies, and Fretilin retreated to the Balibo Administrative Post.[3]: 45 On 14 October an attack was launched in Maliana.[4] Five western journalists, now known as the Balibo Five, were killed by Indonesian forces on 16 October[1] as Balibo was conquered.[3]: 46 The October UDT advances in Balibo, the Atabae Administrative Post, Maliana, and the Bobonaro Administrative Post took place under the cover of Indonesian fire support.[2]: 417 The offensive was the most successful along the coast where their forces had naval support, and with advantage unable to be gained inland the October offensive eventually stalled. Indonesia officially denied the involvement of its troops, stating the attacks were the responsibility of East Timorese "partisans".[3]: 51 Fearing a coup, Fretilin began to arrest Apodeti supporters who remained in East Timor.[3]: 48 Fretilin also informed the United Nations Security Council that it would resist any Indonesian attack.[3]: 61

On 25 October Fretilin again appealed to Portuguese authorities to return to Dili.[3]: 46 A meeting between the Portuguese and Indonesian governments from 1–2 November resulted in a statement of joint support for the resumption of negotiations, although this was not matched by Indonesian actions on the ground. Other Portuguese diplomatic efforts did not produce results, and the Coup of 25 November 1975 meant the Portuguese government no longer had the capacity to intervene in events.[3]: 44 Indonesia proposed a conference in Darwin to discuss events, but this was later cancelled due to the Indonesian insistence that it shift to Bali.[4]

On 20 November the Indonesian offensive resumed, with Indonesia providing air support in addition to naval support. [3]: 51 On 24 November Fretilin requested a United Nations peacekeeping mission.[1] Fighting continued and Atabae Administrative Post was lost to pro-Indonesian forces,[2]: 417–418 having been until then defended by East Timorese soldiers who were part of a Portuguese cavalry company.[3]: 51 This meant the attacking forces had a clear route to Dili.[4]

As the clandestine Indonesian offensive continued to no Portuguese protest, Fretilin began to explore the possibility of independence. A delegation including Mari Alkatiri and César Mau Laka sent to Africa in November reported that 25 countries would recognise East Timorese independence.[3]: 54 Fretilin leaders came to the conclusion that there was little advantage in continuing to seek international support by maintaining ties with Portugal.[2]: 417–418 A 55-article constitution was rapidly drafted.[3]: 56 A declaration of independence was planned for 1 December, which in Portugal marked the start of the Portuguese Restoration War which led to independence from Spain. However, Indonesian advances led to the timetable being accelerated.[3]: 54–55

On 28 November 1975 Fretilin declared independence as the Democratic Republic of East Timor. Following this, the four opposing parties declared the territory part of Indonesia, and Indonesia provided open and public support to these parties. Portugal and Australia rejected both declarations, and called for a United Nations–led settlement, although none emerged.[2]: 411, 417–418

The Fretilin declaration took place in front of Dili's Government Palace, where the Portuguese flag was lowered and the Flag of East Timor was raised, and the national anthem "Pátria" was sung. Due to the rushed timetable not all Fretilin leaders were present, although there was a crowd of around 2,000 people. The next day, Francisco Xavier do Amaral was declared the first President of East Timor.[3]: 55 On 1 December, a Council of Ministers was appointed.[3]: 56

Aftermath

The withdrawal of Portuguese authorities during the civil war contributed to the ability of Indonesia to invade.[3]: 7 Many ethnic Chinese moved to urban areas or fled the country altogether due to the conflict.[3]: 50 The breakout of civil war and the less than a month of fighting from August to September 1975[4] killed between 1,500 and 3,000 people. These numbers include mass killings by both Fretilin and UDT forces. In some cases, both sides killed prisoners of war.[3]: 43 Most deaths occurred in the central mountainous areas, with perhaps less than 500 killed in Dili.[5]: 19 After Indonesia invaded, Apodeti prisoners were also killed. Especially in rural areas, vigilante justice and revenge killings occurred as the chaos provided both opportunity and a free flow of weapons.[3]: 47–48

An independent East Timor was recognised by Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Sao Tomé and Príncipe, all also former Portuguese colonies. Support was also received from China, Cuba, and Vietnam.[1][2]: 411 [3]: 58 Shortly after the declaration of independence, Indonesian forces raised the Indonesian flag in the capital city of Oecusse, Pante Macassar, where there was no organised armed resistance.[10] On 29 November, Indonesia acknowledged the request for annexation given by anti-Fretilin parties, and officially accepted the request on 1 December when Indonesian foreign secretary Adam Malik declared "Diplomacy is over".[3]: 57

On 2 December Australia issued a warning for all its citizens to leave East Timor, prompting the Red Cross to evacuate to Atauro.[3]: 58, 61, 63 On 4 December Marí Alkatiri, Abílio Araújo, José Ramos-Horta, Rogério Lobato, and Roque Rodrigues left on a diplomatic mission to gain support for the new government.[4] United States President Gerald Ford was in Jakarta to meet Suharto on 6 December, and did not dissuade Suharto despite expecting the invasion to occur after his departure. The Indonesian parliament issued statements rejecting the declaration of independence and stating there was a "desire" in East Timor to join Indonesia. Anticipating Indonesian invasion, many people left Dili, including all foreign reporters except for Roger East, who was later executed by Indonesian forces.[3]: 58, 61, 63

Indonesia openly invaded and took over the East Timorese capital through the Battle of Dili on 7 December. Fretilin forces retreated to the mountainous interior,[2]: 411 where weapons and supplies had been stockpiled in anticipation of a war.[2]: 418–419 Portuguese authorities fled Atauro on 8 December[1] on the ship Afonso Cerqueira.[4] Fighting continued as Indonesia slowly took control of the territory. Active resistance continued until 1979, after which resistance switched to guerrilla warfare.[1] On 16 December 1975 Indonesia annexed Oecusse,[4] and on 17 December 1975 Indonesia established the Provisional Government of East Timor. The whole of East Timor was formally annexed on 17 July 1976.[3]: 68

The Indonesian invasion of East Timor received international condemnation, and led to the severance of diplomatic ties with Portugal. The United Nations Security Council called for Indonesia to withdraw. Indonesian foreign secretary Adam Malik initially stated that the Indonesian forces involved with the invasion were marines who would withdraw after the establishment of a new Apodeti-led government, whom Indonesia would assist in the conduct of an Act of Free Choice. Indonesia later stated that the forces involved were volunteers, and ignored the international condemnation.[2]: 418 Portugal never formally relinquished its sovereignty,[11] and modified its constitution on 31 March 1976 to include a commitment to East Timorese independence.[4] Indonesian rule over the territory, recognised only by Australia,[11] lasted until 1999, when an independence referendum was held and the territory transitioned to the control of the International Force East Timor. East Timor became an independent country on 20 May 2002.[1][4]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Frédéric Durand (14 October 2011). "Three centuries of violence and struggle in East Timor (1726–2008)". SciencesPo. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Stephen Hoadley (1976). "East Timor: Civil War — Causes and Consequences". Southeast Asian Affairs. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute: 411–419. JSTOR 27908293.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi "Part 3: The History of the Conflict" (PDF). Chega! The Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation Timor-Leste. Dili: Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor. 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2024 – via East Timor & Indonesia Action Network.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Frédéric Durand; Christine Cabasset-Semedo, eds. (2009). "Chronology 1974-2009". East-Timor How to Build a New Nation in Southeast Asia in the 21st Century?. Carnets de l’Irasec. Vol. 9. Institut de recherche sur l’Asie du Sud-Est contemporaine. pp. 233–267. doi:10.4000/books.irasec.632. ISBN 978-2-9564470-8-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Issue on East Timor" (PDF). United Nations. August 1976. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kammen, Douglas (20 August 2015). "High Colonialism and New Forms of Oppression, 1894-1974". Three Centuries of Conflict in East Timor. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813574127. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Gerald Stone (3 September 1975). "Portuguese Timor's War: Untreated Wounded, P.O.W. Beatings". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b c John Whitehall (October 2010). "Among the Quick and the Dead – East Timor, 1975" (PDF). Quadrant Magazine. Vol. 54, no. 10. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Ian Stewart (13 September 1975). "Leftist Front in Timor Holds a Victory Celebration". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ Laura S. Meitzner Yoder (June 2016). "The formation and remarkable persistence of the Oecusse-Ambeno enclave, Timor". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 47 (2). The National University of Singapore: 299–303. doi:10.1017/S0022463416000084.

- ^ a b G.V.C. Naidu (December 1999). "The East Timor Crisis". Strategic Analysis: A Monthly Journal of the IDSA. XXIII (9).