Guilloché

Guilloché (French: [ɡijɔʃe]), or guilloche (/ɡɪˈloʊʃ/), is a decorative technique in which a very precise, intricate and repetitive pattern is mechanically engraved into an underlying material via engine turning, which uses a machine of the same name. Engine turning machines may include the rose engine lathe and also the straight-line engine. This mechanical technique improved on more time-consuming designs achieved by hand and allowed for greater delicacy, precision, and closeness of line, as well as greater speed.[2]

The term guilloche is also used more generally for repetitive architectural patterns of intersecting or overlapping spirals or other shapes, as used in the Ancient Near East, classical Greece and Rome and neo-classical architecture, and Early Medieval interlace decoration in Anglo-Saxon art and elsewhere. Medieval Cosmatesque stone inlay designs with two ribbons winding around a series of regular central points are very often called guilloche. These central points are often blank, but may contain a figure, such as a rose.[3] These senses are a back-formation from the engraving guilloché, so called because the architectural motifs resemble the designs produced by later guilloché techniques.

Uncertain etymology

[edit]The name guilloché is French, dating back at least to the 1770s,[4] and is often said to be called after a French engineer named Guillot, who invented a tool or turning machine. However no dates nor first name are provided for this shadowy figure, and many dictionaries seem suspicious of his existence.[5]

History

[edit]Engine turning machines were first used in the 1500–1600s on soft materials such as ivory and wood. In the 18th century they were adopted for metals such as gold and silver.[6][7] Some accounts give the credit of developing tightly-packed engraved guilloché decoration to the Nuremberg glass-making dynasty of the Schwanhardt family in the 17th century,[8] using a wheel to engrave the glass.

Engine turning machines made of cast iron and heavy wooden bases, with precision machined surfaces were made until circa 1967 (e.g. Neuweiler und Engelsberger). Individuals continue the craft of making these elegant machines, but in limited quantities.[9]

A Guilloche Machine was granted a US Patent in 1968 by Wilhelm Brandstatter.[10] The original assignor was a firm called Maschinenfabrik Michael Kampf KG. A photo of this machine can be seen at Turati Lombardi's history page.[11]

In the 1920s and '30s, automobile parts such as valve covers, which are atop the engine, were also engine-turned. Similarly, dashboards or the instrument panel of the same were often engine-turned. Customizers also would decorate their vehicles with engine-turning panels similarly.

Guilloche describes a narrow instance of guilloche: a design, frequently architectural, using two curved bands that interlace in a pattern around a central space. Some dictionaries give only this definition of guilloche, although others include the broader meaning associated with guilloché as a second meaning. Note that in the original sense, even a straight line can be guilloché, and persons using the French spelling and pronunciation generally intend the broader, original meaning.[12][13][14] Translucent enamel was applied over guilloché metal by Peter Carl Fabergé on the Fabergé eggs and other pieces from the 1880s.[15]

In today’s terminology

[edit]In consequence of the nature of the design, which is usually a series of lines that are, or look very much like they are interwoven into one another, any design engraved on metal, printed, or otherwise erected on surfaces such as wood or stone, that go in a similar style of constant wriggling that interlock – or look like they are interlocking – with one another, is referred to as guilloché.

Some of the more common ones are the following:

- Engraved (in metal, mainly sterling): in fine timepieces (mainly pocket watches), fine pens, jewelry charms, snuffboxes, hair-styling accessories, wine goblets etc. Examples of famous works of Guilloché are the engravings on Fabergé eggs.

- Erected: on stone for architecture, in wood for styling, on furniture or molding, etc.

- Printed: on bank notes, currency or certificates, etc., to protect against forged copies. The pattern used in this instance is called a spirograph in mathematics, that is, a hypotrochoid generated by a fixed point on a circle rolling inside a fixed circle. It has parametric equations. These patterns bear a strong resemblance to the designs produced on the Spirograph, a children's toy.

Other names for guilloché

[edit]The engine turning machine characteristic of guilloché is called by other names in specific uses:

- Rose engine (metalwork)

- Straight line engine turning Tour à guilloché (metalwork)

- Holtzapffel lathe, named after the founder of an ornamental lathe manufacturer John Jacob Holtzapffel

- Decoration lathe (metalwork)

- Damaskeening (watch movements and horology)

- Geometric lathe (security printing)

- Cycloidal engine (security printing)

- Ornamental turning or ornamental lathe (woodcarving).

The different types of the machines refer to different models and different times during the development of the engine-turning machine.

Gallery

[edit]Engraving technique

[edit]-

A red guilloché enamel Boule de Genève

-

Guilloche work with enamel

-

Solar guilloche pattern on a watch movement crown wheel

-

Barley guilloche pattern on a watch movement main plate

Ornament

[edit]-

Assyrian tile with a guilloché border from the North-West Palace at Nimrud (now in modern Iraq), 883-859 BC, glazed earthenware, British Museum, London[16]

-

19th century illustration of multiple polychrome elements of Ancient Greek architecture, including a guillochés on the right, by Jacques Ignace Hittorff

-

Ancient Greek guilloché on an Ionic column of the Erechtheion, Athens, Greece, unknown architect, 421-405 BC[17]

-

Ancient Greek guilloché on a gorytos, 400-336 BC, silver and gold, Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aigai, Vergina, Greece[18]

-

Roman guilloché on the base of a column of the Trajaneum from Pergamon, now in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany, unknown architect, 115-30 AD

-

Roman guilloché on the Orpheus mosaic from the dining room of a Roman house, c.200, natural stone and glass, Pergamon Museum

-

Roman guilloché on a shield, mid 3rd century, painted wood and hide, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, US[19]

-

Renaissance guillochés on some pilasters, part of the Sala dei Gigli frescos, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy, by Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1482-1484

-

Renaissance guillochés on a pharmacy jar called The Campaigns of Julius Caesar, 1580–1581, maiolica (tin-glazed earthenware), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

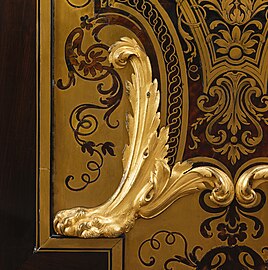

Baroque guilloché on a cabinet, André Charles Boulle, c.1700, oak veneered with Macassar and Gabon ebony, ebonized fruitwood, burl wood, and marquetry of tortoiseshell and brass, gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Rococo guilloché on a tureen with cover, Edme-Pierre Balzac, 1757–1759, silver, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Neoclassical guillochés on a tripod vase, by Wedgwood, c.1805, jasperware, Brooklyn Museum, New York City

-

Neoclassical guilloché on the door of Strada Grigore Cobălcescu no. 6, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect, c.1910

-

Postmodern guillochés on the Harold Washington Library, Chicago, by Hammond, Beeby & Babka, 1991[20]

See also

[edit]- Basse-taille

- Cloisonné

- Filigree

- Fretwork

- Geometric lathe

- Moire (fabric)

- Ornamental turning

- Roulette curve

- Security printing

- Spirograph

References

[edit]- ^ Kirkham, Tony (2024). Tree: Exploring the Arboreal World. Phaidon. p. 264. ISBN 9781838667795.

- ^ Markl, Xavier (2024-05-03). "Technical Perspective: Understanding The Art of Guilloché Dials". Monochrome Watches. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ "Guilloche", Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- ^ Vocabulaire françois, ou, abrégé du Dictionnaire de l'Académie françoise, auquel on a ajouté une nomenclature géographique fort étendue. Ouvrage utile aux François, aux étrangers, & aux jeunes gens de l'un & de l'autre sexe, 1773

- ^ Entry for "Guilloche" in Chambers Dictionary, 1998; the OED record the word from 1842 in English, but do not give an etymology.

- ^ What kind of a machine did Faberge' use to engrave the gold under the enamel on his famous eggs and other irregular shapes? Archived 2004-08-17 at the Wayback Machine by Peter Rowe.

- ^ Guilloché Enameled Luxuries: Engraved memories of a fanciful era Archived 2017-01-08 at the Wayback Machine, Professional Jeweler Archive, March 2001.

- ^ "Schwanhardt", Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- ^ "Argent Blue pens". Archived from the original on 2013-07-27. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ^ GUILLOCHE MACHINE US Patent No. 3,406,454

- ^ "Photo of Guilloche Machine". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ^ The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language By William Dwight Whitney 1889

- ^ Roman Pavements by Henry Colley March 1906

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Review By Lady Randolph Spencer Churchill 1901.

- ^ "eBay Guides - The Guilloché Enamelling Process and Charm Collecting". Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ van Lemmen, Hans (2013). 5000 Years of Tiles. The British Museum Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7141-5099-4.

- ^ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ^ Smith, David Michael (2017). Pocket Museum - Ancient Greece. Thames & Hudson. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-500-51958-5.

- ^ Virginia, L. Campbell (2017). Ancient Rome - Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-500-51959-2.

- ^ Gura, Judith (2017). Postmodern Design Complete. Thames & Hudson. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-500-51914-1.

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Guilloche". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

![Assyrian tile with a guilloché border from the North-West Palace at Nimrud (now in modern Iraq), 883-859 BC, glazed earthenware, British Museum, London[16]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Glazed_Tile.jpg/202px-Glazed_Tile.jpg)

![Ancient Greek guilloché on an Ionic column of the Erechtheion, Athens, Greece, unknown architect, 421-405 BC[17]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/76/Greece-0115_%282215074743%29.jpg/360px-Greece-0115_%282215074743%29.jpg)

![Ancient Greek guilloché on a gorytos, 400-336 BC, silver and gold, Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aigai, Vergina, Greece[18]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/80/%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%83%CF%83%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%BA%CE%B7_-_%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B1%CE%B9%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C_%CE%9C%CE%BF%CF%85%CF%83%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF_1419.jpg/405px-%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%83%CF%83%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%BA%CE%B7_-_%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B1%CE%B9%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C_%CE%9C%CE%BF%CF%85%CF%83%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF_1419.jpg)

![Roman guilloché on a shield, mid 3rd century, painted wood and hide, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, US[19]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/Ag-obj-5959-001-pub-large.jpg/203px-Ag-obj-5959-001-pub-large.jpg)

![Postmodern guillochés on the Harold Washington Library, Chicago, by Hammond, Beeby & Babka, 1991[20]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/96/Harold_Washington_Library_-_Entrance_%2851575567205%29.jpg/432px-Harold_Washington_Library_-_Entrance_%2851575567205%29.jpg)