Pundravardhana

Pundravardhana | |

|---|---|

| unknown (?~1280 BCE)–unknown (?~300 BCE) | |

| |

| Capital | Mahasthangarh |

| Common languages | Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit |

| Religion | Historical Vedic religion Jainism |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Iron Age |

• Established | unknown (?~1280 BCE) |

• Disestablished | unknown (?~300 BCE) |

| Today part of | Bangladesh India (West Dinajpur district, West Bengal) |

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

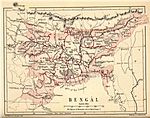

Pundravardhana or Pundra kingdom (Sanskrit: Puṇḍravardhana), was an ancient kingdom of Iron Age South Asia located in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent with a territory that included parts of present-day Rajshahi and parts of Rangpur Division of Bangladesh as well as the West Dinajpur district of West Bengal, India.[1][2][3] The capital of the kingdom, then known as Pundranagara (Pundra city), was located at Mahasthangarh in Bogra District of northern Bangladesh.

Geography

[edit]24°58′N 89°21′E / 24.96°N 89.35°EMahasthangarh, the ancient capital of Pundravardhana is located 11 km (7 mi) north of Bogra on the Bogra-Rangpur highway, with a feeder road (running along the eastern side of the ramparts of the citadel for 1.5 km) leading to Jahajghata and site museum.[4]

Mention in Mahabharata and puranic literature

[edit]According to the epic Mahabharata (I.104.53–54) and puranic literature, Pundra was named after Prince Pundra, the founder of the kingdom, and the son of King Bali. Bali who had no children, requested the sage, Dirghatamas, to bless him with sons. The sage is said to have begotten five sons through his wife, the queen Sudesna. The princes were named Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Pundra and Sumha.[5][6]

Ancient period

[edit]Birthplace of Acharya Bhadrabāhu

[edit]The spiritual teacher of Chandragupta Maurya, Jain Ācārya Bhadrabahu was born in Pundravardhana.[citation needed]

Execution of Ajivikas

[edit]According to Ashokavadana, the Mauryan emperor Ashoka issued an order to kill all the Ajivikas (follower of nāstika or "heterodox" schools of Indian philosophy) in Pundravardhana after a non-Buddhist there drew a picture showing the Gautama Buddha bowing at the feet of Nirgrantha Jnatiputra. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were said to have been executed as a result of this order.[7][8] According to K. T. S. Sarao and Benimadhab Barua, stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be a clear fabrication arising out of sectarian propaganda.[9][10][11] Ashoka's own inscriptions Barabar Caves record his generous donations and patronage to Ajivikas.[12]

Discovery

[edit]Several personalities contributed to the discovery and identification of the ruins at Mahasthangarh. F. Buchanan Hamilton was the first European to locate and visit Mahasthangarh in 1808, C. J. O’Donnell, E. V. Westmacott, and Baveridge followed. Alexander Cunningham was the first to identify the place as the capital of Pundravardhana. He visited the site in 1889.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Hossain, Md. Mosharraf (2006). Mahasthan: Anecdote to History. Dibyaprakash. pp. 69, 73. ISBN 984-483-245-4.

- ^ Ghosh, Suchandra. "Pundravardhana". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- ^ Majumdar, R. C. (1971). History of Ancient Bengal. Calcutta: G. Bharadwaj & Co. p. 13. OCLC 428554.

- ^ Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Devendrakumar Rajaram Patil (1946). Cultural History from the Vāyu Purāna. Motilal Banarsidass Pub. p. 46. ISBN 9788120820852.

- ^ Gaṅgā Rām Garg (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World, Volume 1. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 18–20. ISBN 9788170223740.

- ^ John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 232. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Beni Madhab Barua (5 May 2010). The Ajivikas. General Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Steven L. Danver, ed. (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ Le Phuoc (March 2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ Benimadhab Barua (5 May 2010). The Ajivikas. University of Calcutta. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Nayanjot Lahiri (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7.

- ^ Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 16–19