Latin

| Latin | |

|---|---|

| Lingua Latina | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈlætɪn/ |

| Native to | Vatican City |

| Region | Italian Peninsula and Europe |

| Extinct | Late Latin developed into various Romance languages by the 9th century |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Vatican City Used for official purposes, but not spoken in everyday speech |

| Regulated by | Opus Fundatum Latinitas |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | la |

| ISO 639-2 | lat |

| ISO 639-3 | lat |

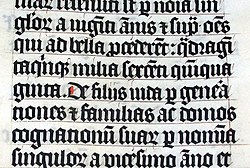

Latin is an ancient Indo-European language originally spoken in Latium, the region immediately surrounding Rome.

Latin gained wide currency, especially in Europe, as the formal language of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire, and, after Rome's conversion to Christianity, of the Roman Catholic Church (although by the time of widespread Christian conversion in Europe, Latin had already become more a language of the Church and of scholars, rather than of the common people). Principally through the influence of the Church, it also became the primary language of later medieval European scholars and philosophers. As an inflectional and synthetic language, Latin relies very little on word order, conveying syntax through a systemic system of affixes attached to word stems. The Latin alphabet, derived from that of the Etruscans and Greeks (each of those themselves derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet), remains the most widely used alphabet in the world.

Although now widely considered a dead language, with few fluent speakers and no native ones, Latin has had a significant influence on many other languages still thriving today, including English, and continues to be an important source of vocabulary for science, academia, and law; it is also used by the Catholic Church, and still evolving, making it technically still alive. Romance languages (Catalan, French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Romansh, Spanish and other regional languages or dialects from the same area) are descended from Vulgar Latin, and many words adapted from Latin are found in other modern languages—including English, where from Latin roughly half of its vocabulary is derived, directly or indirectly.[1] This is part of its legacy as the lingua franca of the Western world for over a thousand years. Latin was only replaced in this capacity by English in the 20th century,[citation needed] though Latin continued to be used in some intellectual and political circles.

The Roman Rite of the Roman Catholic Church has Latin as its official language, and had it as its primary liturgical language until just after the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, when the various vernacular languages of its members were allowed in the liturgy. Latin remains the official language of Vatican City. Classical Latin, the literary language of the late Republic and early Empire, is taught in many primary, grammar, and secondary schools throughout the world, often combined with Greek as the study of Classics, although its role in the syllabus has diminished considerably since the early 20th century.

History

Latin is a member of the Italic languages, and the Latin alphabet is based on the Old Italic alphabet, which is in turn derived from the Greek alphabet. Latin was first brought to the Italian peninsula in the 9th or 8th century BC by migrants from the north, who settled in the Latium region, around the River Tiber, where the Roman civilization first developed. Latin was influenced by the Celtic dialects and the non-Indo-European Etruscan language of northern Italy.

Although surviving Roman literature consists almost entirely of Classical Latin, an artificial and highly stylized literary language whose Golden Age spanned from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD (encompassing the greatest Roman prose writers and poets like Cicero, Virgil, Ovid, Livy, and Caesar, among others), the actual spoken language of the Western Roman Empire was Vulgar Latin, which significantly differed from Classical Latin in grammar, vocabulary, and (eventually) pronunciation.

Interestingly, while Latin long remained the legal and governmental language of the entire Roman Empire, Greek came to be the language most often used among the well-educated elite—as much of the literature and philosophy studied by upper-class Romans had been produced by Greek (usually Athenian) authors. In the eastern half of the Roman Empire, which became the Byzantine Empire after the final split of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires in 395, Greek eventually supplanted Latin as the legal and governmental language, in keeping with the fact that it had long been the spoken language of most Eastern citizens (of all classes).

Legacy

The expansion of the Roman Empire spread Latin throughout Europe, and, eventually, Vulgar Latin began to dialectize, based on the location of its various speakers. Vulgar Latin gradually evolved into a number of distinct Romance languages; a process well underway by the 9th century. These were for many centuries only oral languages, Latin still being used for writing.

For example, Latin was still the official language of Portugal in 1296, after which it was replaced by Portuguese. Many of these "daughter" languages, including Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian, and Romanian, flourished, the differences between them growing greater and more formal over time. Out of the Romance languages, Italian is generally considered the purest descendant of Latin in terms of vocabulary, though Romanian more closely preserves the Classical declension system, and Sardinian is the most conservative in terms of phonology.

Classical Latin and the Romance languages differ in a number of ways, and some of these differences have been used in attempts to reconstruct Vulgar Latin. For example, the Romance languages have distinctive stress on certain syllables, whereas Latin had distinctive length of vowels. In Italian and Sardo logudorese, there is distinctive length of consonants and stress, in Spanish only distinctive stress, and in French length and stress are no longer distinctive. Another major distinction between Romance and Latin is that all Romance languages, excluding Romanian, have lost their case endings in most words, except for some pronouns. Romanian exhibits a direct case (nominative/accusative), an indirect case (dative/genitive), and a vocative, but linguists have said that the case endings are a Balkan innovation.[2]

There has also been a major Latin influence in English. English is Germanic in grammar, Romance in vocabulary, with Greek influence. Sixty percent of the English vocabulary has its roots in Latin.[3] In the medieval period, much of this borrowing occurred through ecclesiastical usage established by Saint Augustine of Canterbury in the 6th Century, or indirectly after the Norman Conquest—through the Anglo-Norman language.

English grammar remains independent of Latin grammar, even though prescriptive grammarians in English have been heavily influenced by Latin (Grammar by Frank Palmer). Attempts to "prohibit" split infinitives, which do not exist in Latin, have been met with resistance from those who believe splitting infinitives occasionally improves the clarity of English.

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, English writers cobbled together huge numbers of new words from Latin and Greek roots. These words were dubbed "inkhorn" or "inkpot" words, as if they had spilled from a pot of ink. Many of these words were used once by the author and then forgotten, but some were so useful that they survived. Imbibe, extrapolate, dormant and employer are all inkhorn terms created from Latin words. Many of the most common polysyllabic "English" words are simply adapted Latin forms, in a large number of cases adapted by way of Old French.

Latin is currently spoken fluently by over a million people.[citation needed]

Latin mottoes are used as guidelines by many organizations.

Grammar

Latin is a synthetic, fusional language: affixes (often suffixes, which usually encode more than one grammatical category) are attached to fixed stems to express gender, number, and case in adjectives, nouns, and pronouns—a process called "declension". Affixes are attached to fixed stems of verbs, as well, to denote person, number, tense, voice, mood, and aspect—a process called "conjugation".

Nouns

There are five Latin noun declensions. Almost every Latin noun belongs to one of these (some nouns are called 'defective nouns' and have unique declension patterns), each of which has a specific set of endings that are added to denote number and case (or grammatical "role") within any given sentence. Each declension and case has unique characteristics, "rules" (such as a more common gender or a vowel placed between many of the endings), and exceptions.

There are seven noun cases. Each case has several uses which are less common and therefore are not noted below:

- Nominative: used when the noun is the subject of the verb or the predicate nominative.

- Genitive: used to indicate possession, origin, or an object which is a part of a whole (known as partitive genitive).

- Dative: used when the noun is the indirect object of the verb, usually with verbs of giving, showing, helping, trusting, or telling. Another use is the dative of reference in which the dative actually "has" the nominative. For this to happen there must be a dative, nominative, and a form of esse.

- Accusative: used when the noun is the direct object of the verb or object of certain prepositions, or to denote movement towards.

- Ablative: used when the noun shows separation or movement from, source, cause, agent, or instrument, or when the noun is used as the object of certain prepositions.

- Vocative: used when the noun is used in a direct address (usually of a person, but not always, as in O Tempora! O Mores!); the only time there is a difference between the vocative and nominative cases is in a masculine, singular, second declension noun.

- Locative: used only with certain nouns (including names of cities, towns, small islands among others) to denote location (for instance Rōmae "in Rome", domī "at home").

Note: The lexical entry for a noun lists the nominative followed by the genitive. An example of this would be mundus, -ī. The "ī" represents the genitive construction of the word, mundī. Some nouns, most commonly in the third declension, undergo a stem change after the nominative, thus: virgo, virginis.

Verbs

Verbs in Latin are usually identified by the four main conjugations—the groups of verbs with similar inflected forms. The first conjugation is typified by infinitive forms ending in -āre, the second by infinitives ending in -ēre, the third by infinitives ending in -ere, and the fourth by infinitives ending in -īre. However, there are a few key exceptions to these rules. There are six general tenses in Latin (present, imperfect, future, perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect), four grammatical moods (indicative, infinitive, imperative and subjunctive), six persons (first, second, and third, each in singular and plural), two voices (active and passive), and a few aspects. Verbs are described by four principal parts:

- The first principal part is the first person, singular, present tense, and it is the indicative mood form of the verb.

- The second principal part is the infinitive form of the verb.

- The third principal part is the first person, singular, perfect tense, active indicative mood form of the verb.

- The fourth principal part is the supine form, or alternatively, the participal form, nominative case, singular, perfect tense, passive voice participle form of the verb. The fourth principal part can show either one gender of the participle, or all three genders (-us for masculine, -a for feminine, and -um for neuter (or "it")).

Education

Although Latin was once the universal academic language in Europe, academics no longer use it for writing papers or daily discourse. Nonetheless, the study of Latin remained an academic staple into the latter part of the 20th century. It is a requirement in relatively few places, and in some universities is not offered. In Italy, however, Latin is still compulsory in secondary schools such as the Liceo classico and Liceo Scientifico, which are usually attended by people who aim to the highest level of education. In Liceo Classico, ancient Greek is also a compulsory subject. About one third of Italian certificated (18 years old) learns Latin for five years.

In Spain, Latin is a compulsory subject for all those who study humanities (students can select from three sorts of study: sciences, humanities or a mixture) in grades 11 and 12. In France and Canada, Latin is optionally studied in secondary school. In Greece, Latin is compulsory for students who wish to study humanities, and is one of the six subjects tested in Greek examinations for entry into humanities University courses.

In Germany, Belgium, Iceland, Austria, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Serbia, Latin is studied at high schools called Gymnasium. In Germany, some 15 % of the student population learn Latin, and a Latin certificate (called Latinum) is a requirement for various university courses.

Latin was once taught in many of the schools in Britain with academic leanings—perhaps 25% of the total.[4] However, the requirement to learn Latin for admission to university for professions in law and medicine was gradually abandoned, beginning in the 1960s. After the introduction of the Modern Language General Certificate of Secondary Education in the 1980s, Latin was gradually replaced by other languages in many schools, but remains taught in others, particularly in the private sector. However only one British exam board now offers Latin (OCR), since the exam board AQA recently stopped offering it.

In the United States Latin is taught in some high schools and some extremely specialized middle schools. There is, however, a growing classical education movement, consisting of private schools and homeschools, that are teaching Latin at the elementary, or grammar school level.

The linguistic element of Latin courses offered in secondary schools and in universities is primarily geared toward an ability to translate Latin texts into modern languages, rather than using it for the purpose of oral communication. As such, the skills of reading and writing are heavily emphasized, and speaking and listening skills are left inchoate.

However, there is a growing movement, sometimes known as the Living Latin movement, whose supporters believe that Latin can be taught in the same way that modern "living" languages are taught, i.e. as a means of both spoken and written communication. This approach to learning the language assists speculative insight into how ancient authors spoke and incorporated sounds of the language stylistically; patterns in Latin poetry and literature can be difficult to identify without an understanding of the sounds of words.

Institutions that offer Living Latin instruction include the Vatican and the University of Kentucky. In Great Britain, the Classical Association encourages this approach, and Latin language books describing the adventures of a mouse called Minimus have been published. In the United States, the National Junior Classical League (with more than 50,000 members) encourages high school students to pursue the study of Latin, and the National Senior Classical League encourages college students to continue their studies of the language.

Many international auxiliary languages have been heavily influenced by Latin; the successful language Interlingua is a modernized and simplified version of the language.

Latin translations of modern literature such as Paddington Bear, Winnie the Pooh, Tintin, Asterix, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Le Petit Prince, Max und Moritz, and The Cat in the Hat are intended to bolster interest in the language.

Latin teachers give way too much homework.

Notes

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-74807/English-language

- ^ Tomić, Olga Mišeska (2001). "The Balkan Sprachbund properties: An introduction to Topics in Balkan Syntax and Semantics" (PDF). University of Leiden Center for Linguistics. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Frederic M. Wheelock, Latin (5th ed.), 1995.

- ^ "That'll Teach 'Em 2: Then and Now".

References

- Bennett, Charles E., Latin Grammar (Allyn and Bacon, Chicago, 1908)

- N. Vincent: "Latin", in The Romance Languages, M. Harris and N. Vincent, eds., (Oxford Univ. Press. 1990), ISBN 0-19-520829-3

- Waquet, Françoise, Latin, or the Empire of a Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Centuries (Verso, 2003) ISBN 1-85984-402-2; translated from the French by John Howe.

- Wheelock, Frederic, Latin: An Introduction (Collins, 6th ed., 2005) ISBN 0-06-078423-7

- Frank Palmer. Grammar

See also

Latin language

- Latin grammar

- Latin spelling and pronunciation

- Latin alphabet

- Golden line

- Latin mnemonics

- Latin-1

- Latin literature

- List of Latin phrases

- Greek and Latin roots in English

- Latin profanity

- List of songs with Latin lyrics

- List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names

- List of Latin words with English derivatives

- List of Latin place names in Europe

- Latin Wikipedia (Vicipaedia)

Latin culture

- Classical Latin

- Ancient Rome

- Brocard

- Carmen Possum

- Internationalism

- Interlingua

- Loeb Classical Library

- Romance languages

Historical periods

External links

- Latin Language, origin and history, grammar, vocabulary, texts, etc.

- Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum, a database of Latin texts and translations

- The Perseus Project, a resource for classical languages and literature

- Latin-English dictionary and Latin grammar, from the University of Notre Dame

- Dictionary of Latin phrases

- omniamundamundis, Latin texts from fourteen ancient Roman authors

- Latin Vulgate, Latin and English translations of the Old and New Testaments of the Bible

- Glossary of Legal Latin Phrases

- Schola Latina Universalis, illustrated Latin textbook

- Latin Online from the University of Texas at Austin

Learn Latin

- Classical Latin course - the most extensive free course available

- Latin for Beginners - an ebook of a 1911 Latin textbook

- Academia Thules offers online courses on Roman History, Philosophy, Archaeology, Religion, Language, Military Arts, Law.

- Free public domain Latin textbooks - from Textkit.com

- Beginners' Latin - UK Government website for learning Latin (UK National Archives)

- Advanced Latin - covers the next stages.

Contemporary usage

- Ephemeris, a Latin newspaper online

- Nuntii Latini, weekly news of the world in Classical Latin published by Radio Finland

- Memoria Press, editorial articles about the benefits of the study of Latin

- Latin Google, Latin version of Google

- Revue "Vita Latina"